Low-income students are more likely to attend schools with less-qualified teachers widening achievement gaps. The Peruvian government’s novel and low-cost nationwide strategy was successful at encouraging highly qualified teachers to apply for jobs in disadvantaged schools.

Editor's Note: An earlier version of this article appeared on VoxEU.

Public education is fundamental to providing equality of opportunity for students of different socioeconomic backgrounds. Yet, in many countries, the widespread problem of teacher sorting (Jackson 2009, Pop-Eleches and Urquiola 2013) threatens this role. Low-income students are more likely to attend schools with less qualified teachers, exacerbating potential achievement gaps (Sass et al. 2012, Thiemann 2018).

How teacher sorting influences inequities in education

Reducing teacher sorting is very relevant for equity purposes. Teachers have a significant effect on students’ test scores (Rivkin et al. 2005), absenteeism, and school suspension (Jackson 2018), as well as long-term outcomes such as college enrolment and employment. Importantly, teachers’ impact is larger among low-performing and low-income students (Aaronson et al. 2007, Araujo et al. 2016). Yet, disadvantaged schools experience more severe shortages of teachers and often fail to attract higher quality professionals (Bertoni et al. 2021). The lack of high-quality teachers in more vulnerable schools has serious implications for inequities in education.

Although the problem of teacher sorting has been well-documented in the literature, policy responses have focused primarily on increasing compensation for hard-to-staff school positions, which is not only expensive but does not always have a significant effect on teachers’ employment decisions (Elacqua et al. 2022).

In this column, we present the results of novel and low-cost strategies implemented nationwide by the government of Peru to reduce teacher sorting (Ajzenman et al. 2024). The programme consisted of two interventions aimed at motivating teacher candidates to apply for job openings in disadvantaged schools, which are typically low-performing, understaffed, and located in poorer and more remote areas. The strategies were designed based on insights from the behavioural economics and psychology literature, particularly with regard to psychological frictions and the determinants of prosocial behaviour.

Why would teachers choose to work at disadvantaged schools?

The decision to work in a disadvantaged school could be seen as prosocial behaviour, as the intent is to benefit others (i.e. students most in need). Prosociality is commonly fostered by a variety of motivations, which can be extrinsic (e.g. monetary incentives) and intrinsic (e.g. feelings of satisfaction derived from helping others in a purely altruistic way; see Ariely et al. 2009). Likewise, identity factors can also matter: teachers who perceive themselves as prosocial or altruistic (i.e. agents of social change) might apply to work in a disadvantaged school in an effort to align their behaviour with the norms associated with their perceived identity (Akerlof and Kranton 2000, Kessler and Milkman 2016).

Designing Peru’s teacher selection process

The programme was designed based on these behavioural insights and implemented across the entire country (except for the provinces of Lima and Callao) during Peru’s centralised 2019 teacher selection process. Participants applied for positions through an online platform after having passed a qualifying exam (Prueba Única Nacional, or PUN). The government sent text messages to applicants before and during the application period and introduced interventions on the application platform just before teachers applied to job vacancies. The experiment consisted of three arms.

The first treatment arm (altruistic identity) sought to make teachers’ prosocial/altruistic identity salient through a combination of three elements:

- A five-minute ‘introspection exercise’ on the application platform that asked teachers to reflect and write about their motivations for choosing teaching as a career (e.g. “Could you tell us why you decided to become a teacher?")

- A set of text-messages priming their prosocial/altruistic identity (e.g. "On the online platform you will find schools where you can generate greater changes in learning. Thank you for choosing to improve lives!")

- Pop-ups on the online application platform designed to prime this facet of their identity, reinforcing the text messages.

The second treatment arm (extrinsic incentives) made an existing programme of monetary incentives for teachers working in disadvantaged schools simpler and easier to understand through a combination of three elements:

- A five-minute exercise on the platform that asked teachers to reflect and write about the potential benefits associated with these monetary incentives (e.g. “How do you think monetary incentives promote the welfare of teachers?")

- A set of text-messages reminding applicants about the rewards associated with disadvantaged schools (e.g. “Consider that in some schools you can receive up to $343 additional to your base salary”)

- Pop-ups on the online application platform that showed simplified information related to the extrinsic rewards. In simplifying the way the information was presented and highlighting the incentives, this treatment arm aimed to capture candidates’ attention while also reducing the psychological frictions associated with the informational complexity of the process and the structure of the reward scheme.

Finally, the control/placebo arm replicated a structure resembling the treatment arms: a neutral reflection exercise on the platform, complemented by a set of neutral text messages (the same number of communications as the treatment arms, but providing general information about the application process, without any components related to altruism, social change, or monetary rewards), and neutral pop-ups on the online application platform. In all of the conditions, disadvantaged schools were highlighted on the platform with an icon, making them easily identifiable by the candidates.

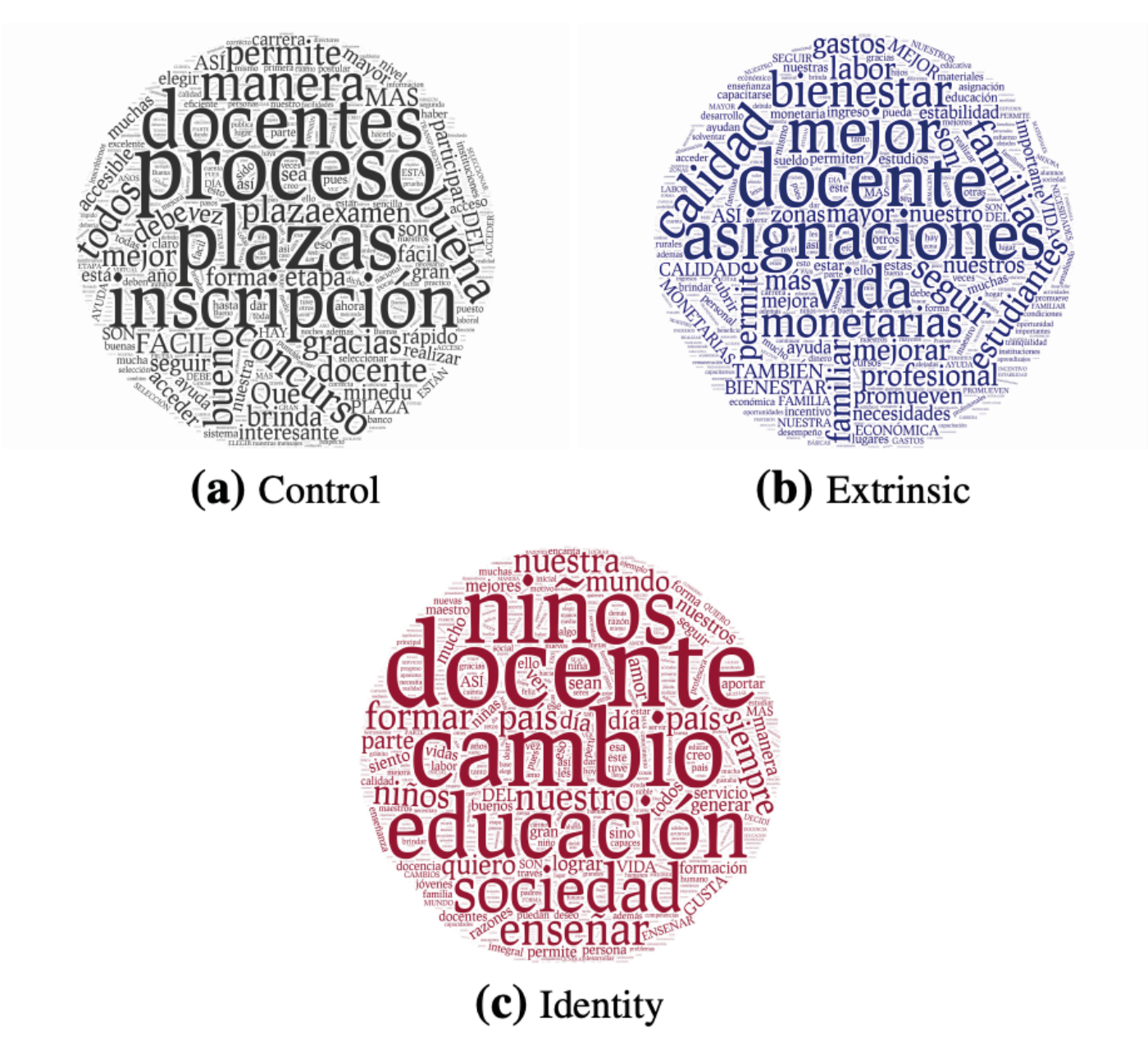

Figure 1: Word cloud, in-platform exercises

Notes: The figure shows the text cloud of teachers’ answers to the exercises in each treatment arm (in the original Spanish). In the Identity treatment arm, the answers often included words closely related to social change. In the Extrinsic treatment arm, several candidates mentioned words or phrases such as "improving quality of life". Finally, candidates in the control group used words related specifically to the teacher-selection process itself. In the case of the Identity treatment, of those who completed the exercise (around 80% of our sample), 50% used words associated with an altruistic identity. This suggests that the reflection exercise seems to have triggered the motivations targeted by each treatment arm.

How altruistic and monetary incentives motivate teachers to apply to disadvantaged schools

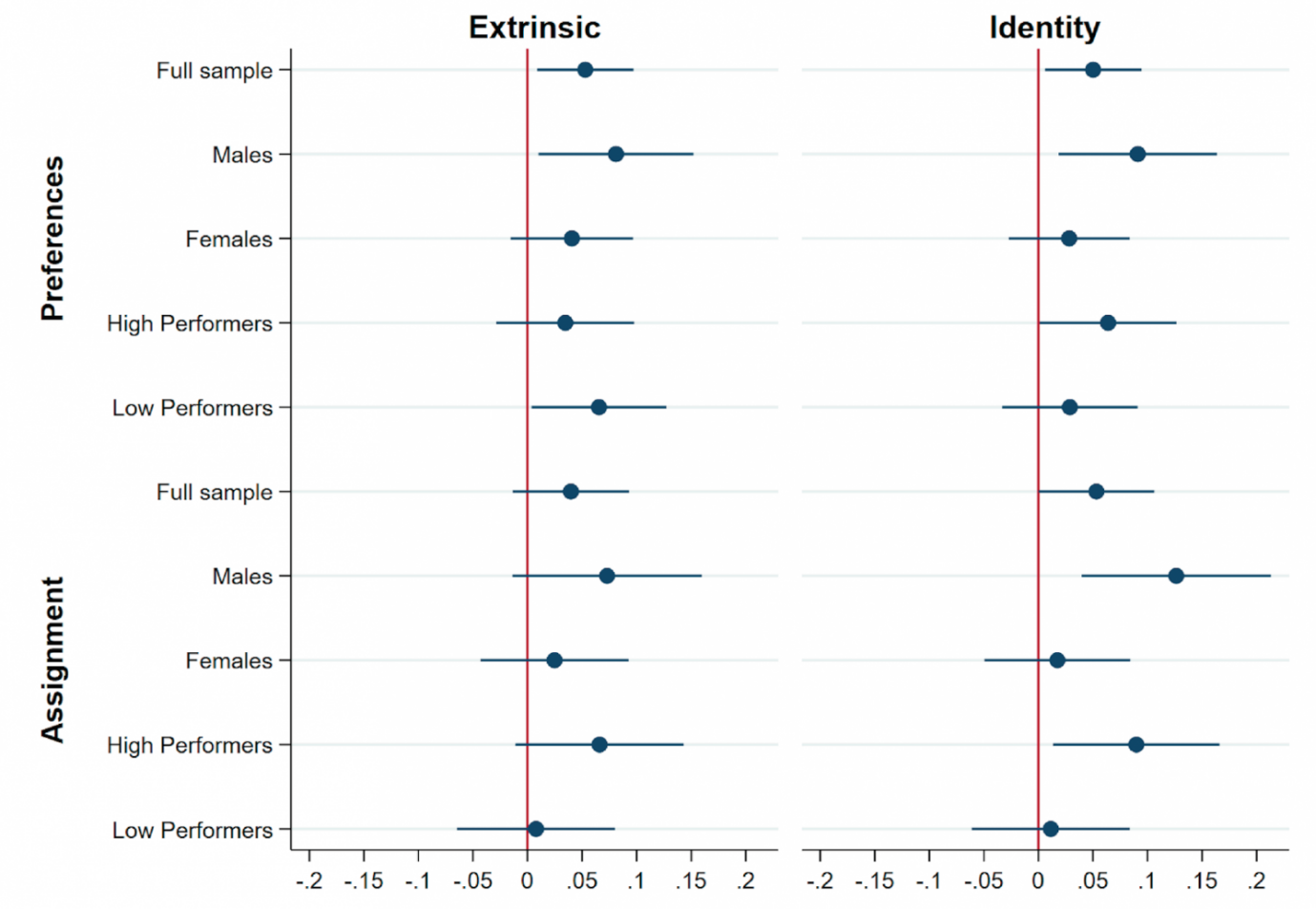

Results are presented for five samples: full sample, only males, only females, high-performers (scored an above-median grade in the qualifying exam) and low-performers (scored a below-median grade in the qualifying exam).

Our results are summarised in Figure 2. We first show that both treatment arms were effective in motivating teachers to apply to disadvantaged schools. The proportion of disadvantaged schools in their choice sets was 2 percentage points higher in both treatment arms (the mean for the control group is 43%). Both treatment arms were driven by male teachers, where the effect was 3 percentage points (Extrinsic) and 3.5 percentage points (Identity), a result perhaps unsurprising considering that female teachers have less flexibility and are less likely to select schools with longer commuting times (such as those targeted in the intervention).

Figure 2: Main results normalised in SD

Notes: ‘Preferences’ is defined as the proportion of disadvantaged schools included in teachers’ choice set. ‘Assignment’ takes a one if the teacher was assigned to a disadvantaged school by the matching algorithm.

After teachers apply for positions, the system clears the market (that is, allocates teachers to a final in-person interview) using an algorithm that matches supply and demand based on teachers’ preferences, available vacancies, and teachers’ performance on the qualifying exam.

We document a significant effect on the probability of being assigned to a disadvantaged school by the algorithm, especially in the Identity treatment. This effect is especially pronounced among male teachers and, notably, high-performing teachers. Why were both treatments similarly effective in influencing teachers’ preferences, yet only the Identity arm impacted their assignments to disadvantaged schools?

A hypothesis to explain this difference between the effectiveness of the treatment arms in terms of teachers’ assignment is related to the composition of teachers affected by each type of intervention. While, on average, both treatments had a similar effect in terms of teachers’ preferences, the Extrinsic arm was particularly effective among teachers with relatively lower performance in the qualifying exam (given that test scores are correlated with income, it is plausible that monetary incentives were more appealing to teachers with lower scores and lower incomes); the opposite was true for the Identity arm. This difference is relevant because teachers with the highest scores are more likely to be assigned to their preferred choices. Moreover, the fact that the Altruistic arm was more effective among high performers seems to be aligned with other studies that show that jobs with a mission tend to attract and retain highly productive workers (Bode et al. 2015, Hedblom et al. 2016).

How governments can improve the equity and efficiency of their education systems

The potential policy implications of these results are substantial. Our paper shows that low-cost, easy to scale behavioural strategies can help to improve the equity and efficiency of the system by mitigating teacher shortages in disadvantaged schools and increasing the flow of qualified teachers to low-performing institutions. We estimate that the cost of filling a teaching vacancy in a disadvantaged school using either of the two strategies evaluated in this paper is approximately $13 per vacancy. In a time when government revenues in many developing countries are declining, low-cost interventions that prime candidates' intrinsic or extrinsic motivations provide a cost-effective way to encourage teachers to apply to disadvantaged schools.