The size of governments varies across countries and changes over time. A key factor in the growth of the size of governments is their ability to extract a significant share of the national income through taxation. This section discusses the evidence on constraints to effective taxation and enforcement, and the implications of these constraints for policy design.

Information trails and third-party reporting

A tax authority that manages to have a high level of effective taxation hinges on a strong enforcement system. One of the pillars of enforcement is information. In most developed countries a significant share of taxes are collected through third-party institutions such as employers, banks and other financial institutions. Based on random audits data in Denmark, Kleven et al. (2011) show that compliance with income taxes is stronger whenever such third-party reporting is in place. Third-party reporting can take various forms. For example, when an employer submits information to the tax authority on the wages paid to employees, this constitutes third-party information. Another example is a financial institution that provides information to the tax authority on the amount of capital income it has paid out to an account holder.

The existence of third-party reporting improves enforcement by creating paper trails on the activities of firms and citizens. Third-party institutions generally have a large number of employees, clients and business partners, and they need to use accurate records to carry out complex activities. These records are often seen by the employees of the firm itself (including in the case of a wage payment), and the business partners also ‘see’ the records by virtue of being either the client or the supplier in the transaction. Kleven et al. (2016) show that while the firm could in principle collude with its employees and business partners to under-report the value of its activities to government, this becomes increasingly hard to sustain when the number of employees and/or partners is larger. For this reason, due to the existence of a large number of informed employees/partners, and the existence of underlying business records evidence, enforcement based on third-party coverage can be successful.

In Chile, Pomeranz (2015) compellingly shows that the value-added tax (VAT) facilitates tax enforcement by generating information trails on transactions between firms. The VAT is widely adopted across low- and middle-income countries today (Keen and Lockwood 2007). The popularity of the VAT is likely due in part to the built-in incentive structure that creates third-party reported paper trails on transactions between firms – as both the client and the seller are required to report the value of the transaction to the tax authority. While the seller would prefer to under-report this value, the client would prefer to over-report the value (see also Brockmeyer et al. 2024 on the VAT in low- and middle-income countries]. In two experiments, Pomeranz shows that the existence of this paper trail has a preventive deterrence effect on evasion and that a tax enforcement shock transmits through the production chain due to the existence of this paper trail.

These results support the idea that, as the third-party coverage of an economy grows, enforcement will be strengthened and lead to an improved ability to collect taxes. There are, however, three important qualifications that are relevant in low- and middle-income countries. The first is that the paper trail ‘breaks down’ at the final consumer stage if the consumers have no incentive to ask for and maintain receipts from their purchases at retailers. Naritomi (2019) studies an anti-tax evasion programme in Sao Paulo, Brazil, which creates monetary rewards for consumers to ensure that firms report final sales transactions. Naritomi finds that, by enlisting consumers as tax auditors, this programme was effectively able to increase the available third-party information which, in turn, led to a meaningful increase in collected tax revenues. The second point is that there are limits to the effectiveness of third-party reporting when firms and individuals can make offsetting adjustments on margins of activity that are less verifiable. In Ecuador, Carillo et al. (2017) show that when firms are notified by the tax authority about detected revenue discrepancies based on third-party reports, they increase reported revenues but also adjust reported costs, such that the ultimate impact on tax collection is muted. Importantly, firms adjust their inputs in cost-categories that have little or no third-party coverage (e.g. “other administrative costs”). Third, the success of third-party reporting relies on the assumption that the tax authority has a certain capacity to cross-check information reported across parties and, perhaps more importantly, that the firms and individuals in the economy believe in this capacity and, as a result, keep accurate records. Using transaction data from Uganda, Almunia et al. (2024) show that sellers and buyers report different amounts for the same transaction in 79% of cases. Additional analyses show that 75% of Ugandan firms engage in advantageous mis-reporting which leads to a reduction in their tax liability. Thus, third-party reporting is a helpful starting point to improve tax collection but it must be combined with complementary investments in the tax authority’s enforcement capacity.

Beyond the informational capacity, third-party institutions can also help to improve tax collection through withholding. Withholding occurs when the third-party institution remits some or all of the tax due directly to the tax authority. For example, withholding would occur when an employer withholds the estimated tax that is due on an employee’s wage and directly sends the tax payment to the tax authority (on behalf of the taxpayer, effectively). Brockmeyer and Hernandez (2022) show that the use of withholding is more prevalent in lower-income countries, which also apply this tool more broadly and with higher withholding rates than in higher-income countries. These facts suggest that withholding may be particularly desirable for collection purposes in settings with otherwise limited enforcement capacity. Moreover, Brockmeyer and Hernandez (2022) show, using micro-data from Costa Rica, that an increase in the withholding rate led to a significant ultimate increase in the taxes paid by firms. Additional analyses suggest that the surprisingly large, positive impact of withholding on collection operates through both a ‘default remittance’ effect, where firms do not attempt to reclaim the withheld tax to reduce their ultimate tax liability, and an enforcement perception effect, where firms perceive the tax authority to have stronger enforcement capacity following the reform (although the reform only changed the withholding rate). Relatedly, Garriga and Tortarolo (2024) study a reform in Argentina which appointed the task of collecting taxes to large firms. They find that this delegation led to a significant increase in self-reported sales and tax payments among the trading partners with the treated firms, with the effects concentrated among downstream firms that lack significant paper trail coverage.

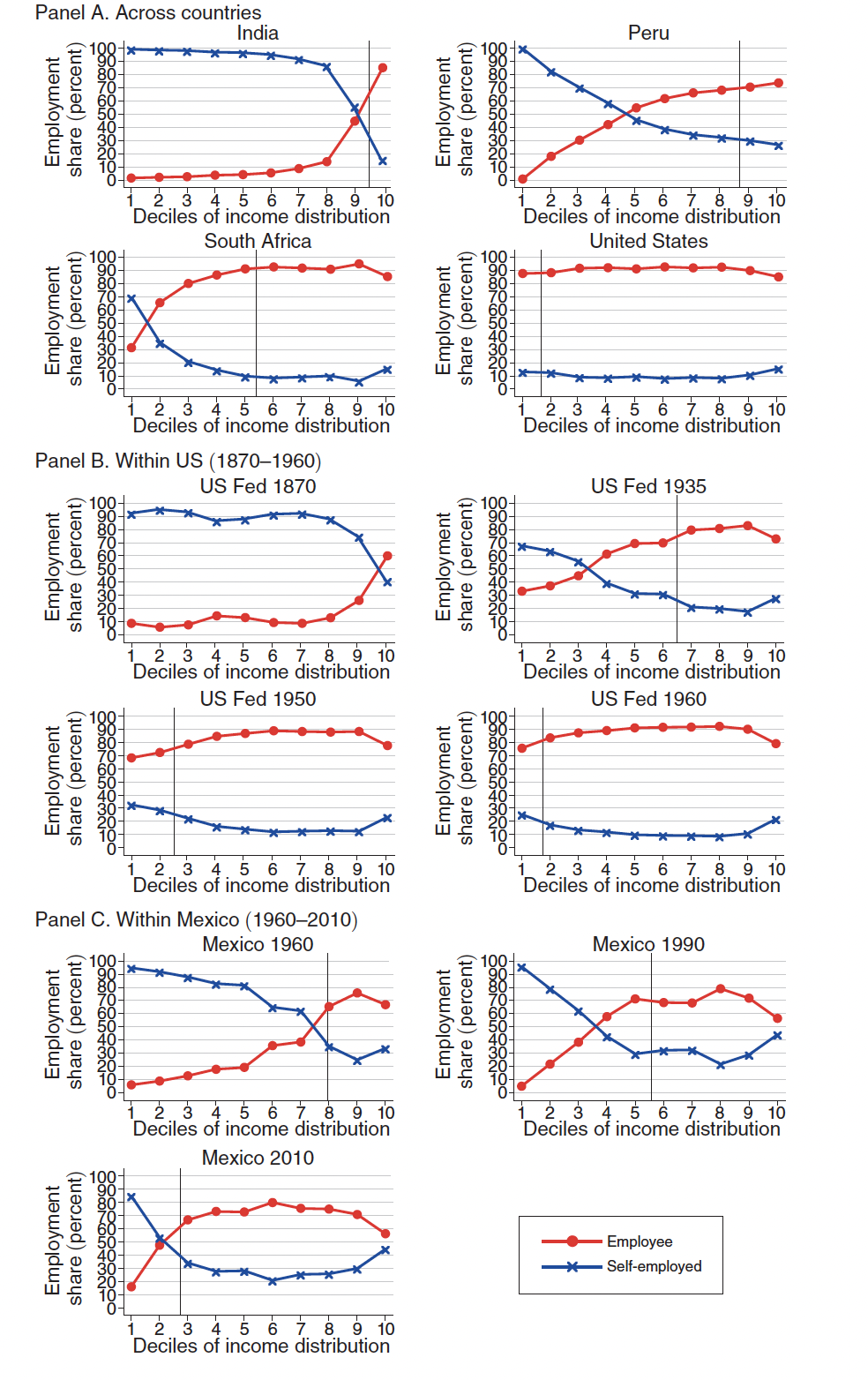

Jensen (2022) constructs a database that covers 100 countries at all income levels today, as well as a long-run time series in the United States (1870-2010) and Mexico (1960-2010), and finds that as countries develop, revenue from income taxes also increase as more of the workforce transitions from self employment to being an employee. Motivated by the Danish evidence on the difference in third-party coverage between employees and the self-employed, and the resulting difference in evasion, Jensen uses the employee share in the active workforce as a proxy for the share of individual income that is enforceable. At low income levels, the employee-share is concentrated at the top of the country’s income distribution (i.e. most employees are amongst the highest earners). As countries develop, the employee share gradually rises at higher levels of income (Figure 1).

Jensen (2022) also finds that at the lowest levels of development, the income tax exemption threshold, the nominal level of income beneath which an individual is legally exempt from paying personal income taxes, is located at the top of the income distribution. As countries develop, the threshold gradually decreases in the income distribution, in close co-movement with increases in employee share to its left. As a result, the size of the personal income tax base grows significantly as countries develop while the share of all taxpayers that are employees remains high, between 85% and 95%, even as the size of the tax base (the share of the income distribution that is subject to the income tax) grows. These findings are consistent with a government’s enforcement costs rising with a higher self-employed share. The transition from self-employment to employee-employment over time improves the government's ability to enforce taxes, expand the tax base and increase income tax revenue.

Figure 1

Motivated by the micro-evidence cited so far on information trails, these descriptive results suggest how the long-run transition from self-employment to employee-employment increases the government’s enforcement capacity and drives expansions of the income tax base.

Limits to enforcement and production efficiency

The results in Jensen (2022) highlight how low- and middle-income countries differ in the extent to which their economy is characterised by information trails. As a result of the much lower third-party coverage, optimal tax policies may look very different than they do in high-income countries. In particular, many low- and middle-income countries implement policies that are at odds with second-best approaches (Gordon and Li 2009, Best et al. 2015) – the idea that, in a context with some informational barriers, tax policies should aim to maximise social welfare with the instruments available that tax observable transactions. An important result in public economics is that second-best approaches should promote production efficiency, i.e. they should seek to minimise distortions on economic choices by firms and households (Diamond and Mirrlees 1971). This result permits taxes on consumption, wages and profits, but precludes taxes on intermediate inputs, turnover and trade. The challenge is that the production efficiency result was derived in an environment with perfect tax enforcement – which is clearly at odds with the situation in low- and middle-income countries that are characterised by limited enforcement capacity (for several reasons, including weak information coverage, constrained human and technological resources, and corruption).

Best et al. (2015) use administrative data from Pakistan to show how, once we allow for tax evasion, it may be desirable for optimal tax policy to implement ‘third-best’ policies that deviate from production efficiency if they lead to less evasion and therefore greater revenue efficiency. Their specific setting is the policy design choice between a firm tax on profits versus on turnover. Pakistan implements a minimum tax scheme, where firms are taxed either on profits or turnover, depending on which tax liability is larger. While a profit tax can be evaded through the over-reporting of costs, this evasion strategy does not help evade the turnover tax. Best et al. (2015) show that turnover taxes, implemented for smaller firms that have more scope to over-report costs, can reduce evasion by up to 70%. Thus, even though the turnover tax is production inefficient relative to the profit tax, it may ultimately be implemented because of its relatively stronger revenue efficiency.

Recent studies have provided related insights on the taxation of firms when evasion is prevalent. Bachas and Soto (2021) find, in the context of corporate taxation in Costa Rica, that firms respond to an increase in the tax rate by reducing revenue but considerably increasing costs - leading to a large elasticity of corporate taxable profits, in the range of 3 to 5. In Honduras, Lobel, Scot and Zúniga (2024) find that corporations over-report true costs when their profits are taxed. These results speak to the design of corporate taxes in the presence of evasion: in particular, the results from Costa Rica suggest that a policy which lowers the statutory rate while broadening the taxable base has the potential to achieve a higher amount of tax revenue collected from these firms.

Balancing investment in enforcement versus other tax reforms

The results above illustrate how governments trade off between different statutory tax policies to raise revenue while accounting for constraints on enforcement. A complementary policy design question is how a tax authority should balance between statutory reforms, on the one hand, and direct investments in enforcement, on the other hand. Keen and Slemrod (2017) provide a theoretical discussion of this policy choice, which is highly relevant in low- and middle-income countries where the tax authority has limited resources and often has to choose one of the two alternatives in order to raise revenue.

In Indonesia, Basri et al. (2021) compare two approaches to increase corporate tax revenues: creation of ‘medium size taxpayer offices’ (MTOs) and changes to the statutory tax rate. The authors find that the administrative reform caused a large increase in taxes collected amongst corporations. One strength of this study is that the authors can compare this return to the returns from a statutory reform in the same exact context (using the same data and based on the same set of corporate firms). Based on the full set of results, the authors conclude that to obtain the increase in corporate income tax paid by the MTO taxpayers alone, the top marginal Corporate Income Tax (CIT) rate on all firms would have to be raised by 8 percentage points. The welfare gain of any reform depends not only on the change in revenues collected but also the impacts on firms (e.g. the change in firms’ administrative costs from complying with taxes under the reformed regime). The authors discuss how it is likely that the welfare gains from raising revenue through improved administration exceed those from increased rates. In other words, low- and middle-income countries appear to have significant space to raise revenue through enforcement reforms and the scope to improve collection may even be stronger than through statutory reforms.

Drawing on multiple sources of policy variation in Mexico City, Brockmeyer et al. (2023) investigate if tax rate increases and enforcement policies raise property tax revenues and whether one instrument is more effective at raising welfare than the other. The analysis emphasises how the revenue gain via either policy must be weighed against the potential hardship it causes to households, including through exacerbating household liquidity constraints. For the property tax, the authors find that welfare can be enhanced by raising rates rather than escalating enforcement.

While the papers in this subsection shed light on potential trade-offs, there are also potential complementarities between statutory and enforcement reforms. Indeed, the ability of governments to collect revenue from a statutory rate increase will be enhanced if there is a stronger supporting enforcement environment. Consistent with this intuition, Bergeron et al. (2024) provide experimental evidence from property taxes in the DRC which show that the revenue maximising tax rate increases with the strength of enforcement.

Finally, it is important to note that while there is some direct evidence on the efficiency costs of tax systems in low- and middle-income countries, more work is needed in this area. Several studies have used the VAT as a setting to directly study the real impacts of taxation on firm outcomes, leveraging the various institutional features (such as size thresholds for registration, differing VAT rates by products, and delays in processing and disbursing VAT refunds) - see Brockmeyer et al. (2024) for a detailed review of the VAT in practice in low- and middle-income countries. Gadenne et al. (2022) find there is significant segmentation in trade between VAT and non-VAT registered firms around the threshold for VAT registration. Liu et al. (2021) and Harju et al. (2019) find that VAT registration thresholds affect firm growth and inter-firm trade in several European contexts. Relatedly, there may be important efficiency costs arising from imperfections in the processing of tax credits or refunds, which in turn may alter firms’ demand for specific inputs. Chandra and Long (2013) find large effects of VAT rebates on export volume of Chinese firms. Some of these real effects arise due to limited administrative and enforcement capacities, which impact how a particular tax is implemented in practice (versus in theory). Similarly, when evasion is prevalent due to limited enforcement, there can also be efficiency costs on other firms. For example, in Italy, Di Marzio et al. (2024) show that individual firms’ non-compliance decisions create an uneven playing field and distort the economic outcomes of firms that compete with the evading firms, leading to an overall reduction in market productivity. Given the natural importance of efficiency costs as a theme that links taxation to economic growth, providing rigorous and direct evidence on these costs is an area that deserves more attention in the future.

References

Almunia, M, J Hjort, J Knebelmann, and L Tian (2024), "Strategic or confused firms? Evidence from 'missing' transactions in Uganda", The Review of Economics and Statistics, 106(1): 256–265.

Bachas, P, and M Soto (2021), "Corporate taxation under weak enforcement", American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 13(4): 36-71.

Basri, M C, M Felix, R Hanna, and B A Olken (2021), "Tax administration versus tax rates: Evidence from corporate taxation in Indonesia", American Economic Review, 111(12): 3827-3871.

Bergeron, A, G Tourek, and J L Weigel (2024), "The state capacity ceiling on tax rates: Evidence from randomized tax abatements in the DRC", Econometrica, 92(4): 1163-1193.

Best, M C, A Brockmeyer, H J Kleven, J Spinnewijn, and M Waseem (2015), "Production versus revenue efficiency with limited tax capacity: Theory and evidence from Pakistan", Journal of Political Economy, 123(6): 1311-1355.

Brockmeyer, A, and M Hernandez (2022), "Taxation, information, and withholding: Evidence from Costa Rica", Working Paper.

Brockmeyer, A, G Mascagni, V Nair, M Waseem, and M Almunia (2024), "Does the value-added tax add value? Lessons using administrative data from a diverse set of countries", Journal of Economic Perspectives, 38(1): 107-132.

Brockmeyer, A, A Estefan, K R Arras, and J C S Serrato (2023), "Taxing property in developing countries: Theory and evidence from Mexico", National Bureau of Economic Research, No. w28637.

Carillo, P, D Pomeranz, and M Singhal (2017), "Dodging the taxman: Firm misreporting and limits to tax enforcement", American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 9(2): 144-164.

Chandra, P, and C Long (2013), "VAT rebates and export performance in China: Firm-level evidence", Journal of Public Economics, 102: 13-22.

Di Marzio, I, S Mocetti, and E Rubolino (2024), "Market Externalities of Tax Evasion", Available at SSRN 4892683.

Diamond, P A, and J A Mirrlees (1971), "Optimal taxation and public production I: Production efficiency", American Economic Review, 61(1): 8–27.

Gadenne, L, T K Nandi, and R Rathelot (2022), “Taxation and Supplier Networks: Evidence from India”, Working Paper.

Garriga, P, and D Tortarolo (2024), “Firms as tax collectors”, Journal of Public Economics, 233: 105092.

Gordon, R, and W Li (2009), "Tax structures in developing countries: Many puzzles and a possible explanation", Journal of Public Economics, 93(7-8): 855-866.

Harju, J, T Matikka, and T Rauhanen (2019), “Compliance costs vs. tax incentives: Why do entrepreneurs respond to size-based regulations?”, Journal of Public Economics, 173: 139–164.

Jensen, A (2022), "Employment structure and the rise of the modern tax system", American Economic Review, 112(1): 213-234.

Keen, M, and B Lockwood (2007), "The value-added tax: Its causes and consequences", IMF Working Paper 07/183.

Keen, M, and J Slemrod (2017), "Optimal tax administration", Journal of Public Economics, 152: 133-142.

Khan, A Q, A I Khwaja, and B A Olken (2016), "Tax farming redux: Experimental evidence on performance pay for tax collectors", Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(1): 219-271.

Kleven, H J, C T Kreiner, and E Saez (2016), "Why can modern governments tax so much? An agency model of firms as fiscal intermediaries", Economica, 83(330): 219-246.

Kleven, H J, M B Knudsen, C T Kreiner, S Pedersen, and E Saez (2011), "Unwilling or unable to cheat? Evidence from a tax audit experiment in Denmark", Econometrica, 79(3): 651-692.

Liu, L, B Lockwood, M Almunia, and E H F Tam (2021), “VAT Notches, Voluntary Registration, and Bunching: Theory and U.K. Evidence”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 103(1): 151–164.

Lobel, F, T Scot, and P Zúniga (2024), "Corporate taxation and evasion responses: Evidence from a minimum tax in Honduras", American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 16(1): 482-517.

Naritomi, J (2019), "Consumers as tax auditors", American Economic Review, 109(9): 3031-3072.

Pomeranz, D (2015), "No taxation without information: Deterrence and self-enforcement in the value-added tax", American Economic Review, 105(8): 2539-2569.

Contact VoxDev

If you have questions, feedback, or would like more information about this article, please feel free to reach out to the VoxDev team. We’re here to help with any inquiries and to provide further insights on our research and content.