Editor's note: This section is based on Bachas et al. (2024). Please refer to the paper for a more detailed review.

Taxes are sometimes thought of primarily as a tool to raise revenue to fund productivity enhancing public goods. But taxes can also serve redistributive purposes – what role can or might taxation play in reducing income inequality in low- and middle-income countries? This question is important as income inequality is high in these countries, and has either stabilised or increased over the past 30 years. Recent estimates from Africa show that, at the regional level, the share of pre-tax income of the top 10% is close to 55% (Chancel et al. 2023); similarly high levels of inequality are found in other large low- and middle-income countries, including Brazil at 58%, China at 43%, India at 57%, and Indonesia at 47% (World Inequality Database at https://wid.world/).

Statutory, de facto and economic incidence

When evaluating the equity effects of a tax system, economists and policymakers focus on three key aspects of tax payment:

- Statutory Incidence: This aspect defines the taxes legally imposed by the government and identifies who is expected to pay taxes directly. For example, many countries have a progressive personal income tax where marginal tax rates rise with income, resulting in a higher statutory tax burden for wealthier individuals.

- De Facto Incidence: This reflects who actually pays taxes, taking into account the possibility of tax evasion or avoidance. The capacity and willingness to evade taxes can vary among individuals. For instance, wealthier individuals often have access to advanced evasion or avoidance strategies, reducing their actual tax burden. If such strategies are less available to lower-income individuals, it decreases the progressivity of the tax system, as the actual tax burden gap between rich and poor narrows compared to the statutory gap.

- Economic Incidence: This describes how taxes influence market prices, potentially shifting the tax burden from the entities that remit taxes to those with whom they conduct business. For example, while businesses collect sales or value-added taxes, the cost is often passed on to consumers through higher prices.

These three elements together shape the equity impact of a tax system, altering the distribution of income from “pre-tax” to “post-tax.”

A significant challenge for tax collection in low- and middle-income countries is the presence of a substantial informal sector within their economies (Ulyssea et al. 2023). Here, informality is defined as the lack of complete tax payment by firms or individuals. Informality can occur either because a firm or individual is evading part or all of the taxes they are legally obligated to pay according to the tax code, or because they are legally exempt from any tax payment under the tax code.

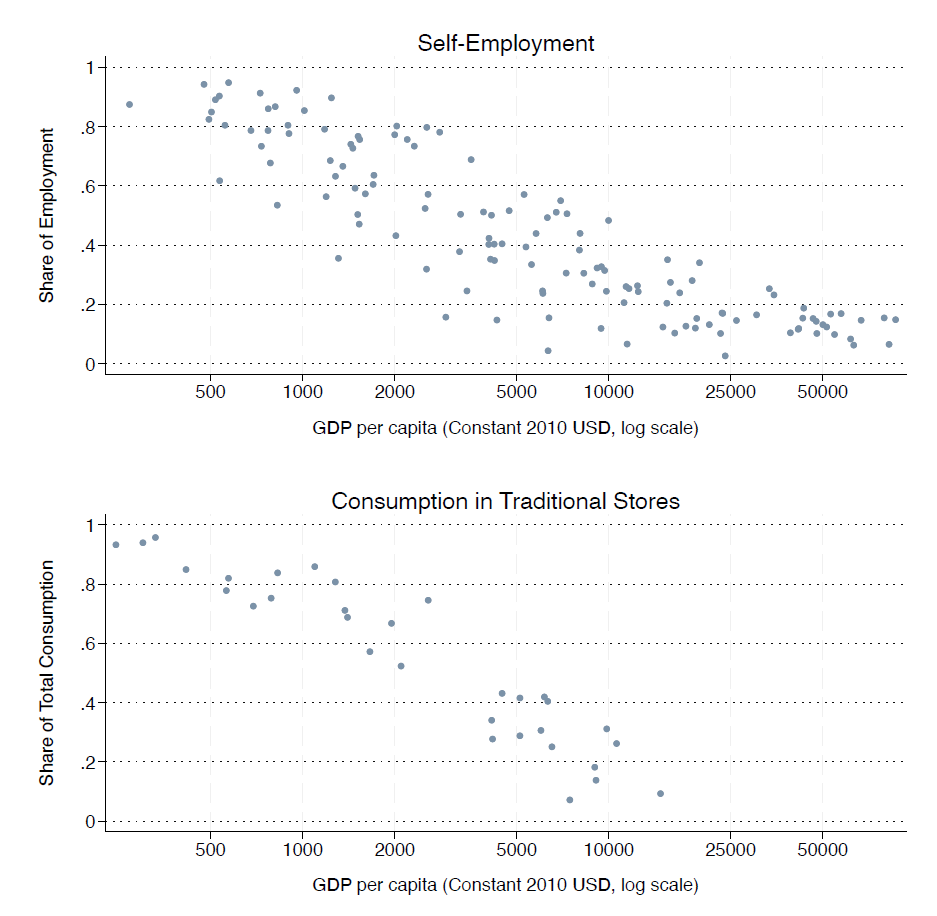

Figure 2 introduces two proxy measures for informality at the national level and examines their relationship to development. The first proxy is the proportion of self-employed individuals within the active workforce. Globally, including in developed countries, it is more difficult to enforce income tax collection from the self-employed compared to employees, primarily due to the lack of third-party reporting and withholding mechanisms, which employers typically handle for their employees (Section 3). The second proxy is the percentage of household spending at traditional retailers—such as street stalls, public markets and corner stores (often referred to as "non–brick and mortar" stores), as well as home-based production. Compared to modern retailers like supermarkets and department stores, traditional retailers are generally much smaller in terms of sales volume and physical size, employ fewer workers, have a more limited customer base, and interact with fewer suppliers. These characteristics are strongly linked to informality, making the proportion of household budgets allocated to traditional stores a valuable proxy for informal consumption (Bachas et al. 2023).

Figure 2

Figure 2 reveals a clear trend: the size of the informal sector within the economy significantly diminishes as GDP per capita increases. In low-income countries, informal consumption accounts for 86%, which drops sharply to 12% in high-income countries. Similarly, informal labour comprises 81% of the workforce in low-income countries but falls to 16% in high-income countries. This stark contrast highlights a major challenge for tax design in low- and middle-income countries, where a substantial portion of economic activities and participants remain outside the formal tax system. Conversely, high-income countries have a more comprehensive tax net. As we will see below, whenever these measures of informality vary systematically with household income within a country, they will have important implications for the overall equity of a tax system.

Direct and Indirect Taxation: Personal Income Tax and VAT

In low- and middle-income countries, the tax structure is defined by relatively low personal income tax revenues, heavy dependence on indirect taxes, and a significant portion of economic activity occurring in the informal sector. This configuration affects the equity characteristics of two primary tax instruments: personal income tax and value-added tax (VAT). Two insights can be established based on recent research.

The first key insight draws from Jensen's (2022) findings on the evolution of the personal income tax base and employment structure as countries develop. Enforcement constraints, which occur when a significant portion of the workforce consists of self-employed individuals, heavily influence statutory decisions regarding tax policies. Governments often face difficulties in taxing lower-income individuals who are primarily self-employed, leading them to exempt large segments of the workforce from personal income tax. This results in a narrow tax base, which limits the personal income tax's capacity to serve as a substantial revenue source in low- and middle-income countries. This narrow tax base impacts the "optimal" methods for achieving redistribution according to economic theory. The prominent result in public finance, as outlined by Atkinson and Stiglitz (1976), suggests that redistribution should ideally be achieved exclusively through personal income tax, implying that using other tax instruments like consumption taxes for redistribution is suboptimal. However, this theoretical result assumes that governments can apply broad and flexible income tax schedules across the entire income distribution—a premise that does not align with the realities faced by most low- and middle-income countries (Figure 1). When considering the actual enforcement constraints influencing statutory tax policies, utilising consumption taxes for both revenue generation and equity objectives can be a pragmatic and effective approach to tax policy (Huang and Rios 2016).

The second key insight concerns the equity effects of indirect (consumption) taxes in low- and middle-income countries. Conventional wisdom, informed by the experience of high-income countries, suggests that consumption taxes have limited or negative redistributive effects because they tax households in proportion to their consumption (Warren 2008). Given that low- and middle-income countries rely more heavily on indirect taxes and less on personal income taxes, one might conclude that their tax systems do little to achieve redistribution. However, considering the actual impact of consumption taxes can significantly alter this perspective.

Lower-income households are more likely to shop in the informal sector. Therefore, a consumption tax that effectively applies only to formal purchases may have positive redistributive effects. To determine if there is a systematic relationship between the type of store where households shop and their income level, it is essential to have data on the place of purchase for each expenditure. Bachas et al. (2023) provide this data by compiling and harmonising household expenditure diaries for 32 low- and middle-income countries, enabling them to observe the type of store for each purchase. Drawing on evidence from retail censuses and the literature on informality (e.g. Lagakos 2016), they classify expenditures at modern retailers as formal and those at traditional retailers or from home production as informal.

Bachas et al. (2023) explore how shopping patterns correlate with household income in order to measure a modified Engel curve. A traditional Engel curve illustrates how an increase in household income changes the proportion of income spent on a particular good. The authors adapt this concept to reflect the widespread informality in the setting, introducing the Informality Engel Curve. This curve demonstrates how changes in household income affect the extent to which a household purchases from the informal sector. For example, in Rwanda, the share of household budget spent in informal stores decreases from 90% for the lowest income decile to 70% for the highest decile. In Mexico, it declines from 55% to 25%.

The presence of an Informality Engel Curve carries significant implications for the equity of consumption taxes. Firstly, its downward slope suggests that, under certain assumptions regarding economic incidence, consumption taxes are effectively progressive, affecting higher earners more. Secondly, there is a substantial overlap between consumption of food items and purchases made in informal stores. Many countries globally implement reduced tax rates on food products to enhance equity, driven by the downward-sloping conventional Engel curve for food consumption. However, in practice, this policy often fails to enhance progressivity in low- and middle-income countries because much of the food consumed by poorer households is already effectively exempt from taxation. Thirdly, while recognising that the Informality Engel Curve can enhance the equity benefits of a consumption tax, it also amplifies the economic distortions in the economy relative to a setting without informal consumption. Finally, the optimal extent to which there should be differentiation of consumption tax rates across goods will be limited—both because the equity gains from subsidising necessity goods relative to other goods is limited, and because such rate-differentiation introduces additional efficiency costs.

Implicit in our preceding discussion has been an assumption regarding economic incidence: namely, that consumption taxes are fully reflected in prices at formal stores, while they have minimal impact on prices at informal stores. How realistic is this assumption? To assess the validity of this economic incidence assumption, one needs data on (tax-inclusive) prices from both formal and informal stores, along with evidence from a tax reform that alters the consumption tax rate. Such data requirements were met in Mexico, where Bachas et al. (2023) analysed a reform that increased the value-added tax rate in select regions of the country in 2014. Consistent with the baseline assumption, the reform resulted in a significant price pass-through of the increased consumption tax rate at formal stores, while the pass-through at traditional stores, although present, was considerably smaller.

Taxing the top of the income distribution

Currently, a primary focus of global policy is devising effective methods to tax the wealthy in a globalised economy (Scheuer and Slemrod 2021, Bergolo et al. 2022, Bergolo et al. 2023), a move that would significantly enhance progressivity. However, two critical challenges hinder the enforcement of taxes on high-income individuals. Firstly, affluent individuals derive a substantial portion of their income from businesses they directly or indirectly control (for US-based evidence, see Kopczuk and Zwick 2020). Taxing business owners is complex due to their ability to strategically allocate income across various categories (such as salaries and profits), defer taxation, and utilise business income for personal consumption. Effective enforcement requires robust audit capabilities, the ability to link businesses to individuals, and access to third-party information on all income sources - resources often limited in low- and middle-income countries. Secondly, high-income individuals often hold wealth abroad, particularly in tax haven jurisdictions with low tax rates and limited transparency. As of 2022, offshore financial wealth in tax havens is estimated to be equivalent to 12% of global GDP (Alstadsæter et al. 2023). While not all offshore wealth is unreported, histo\beginrically a significant portion remains undisclosed, even in countries with strong tax enforcement capabilities. Low- and middle-income countries are disproportionately affected; financial wealth held in tax havens accounts for up to 18% of GDP in Africa and the Middle East, 13% in Latin America, and 5% in Asia, compared to 12% in Europe and 7% in North America (Alstadsæter et al. 2018).

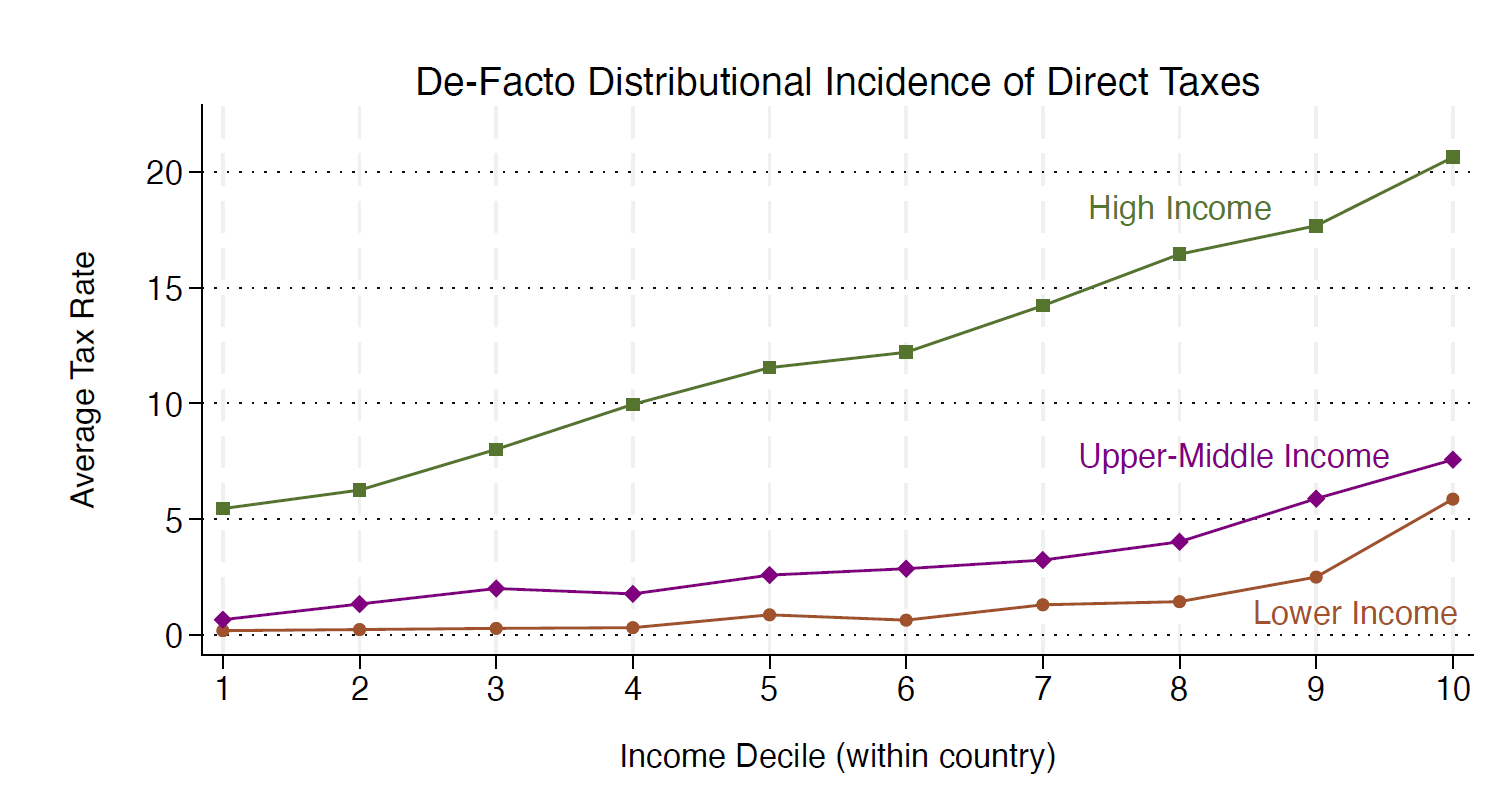

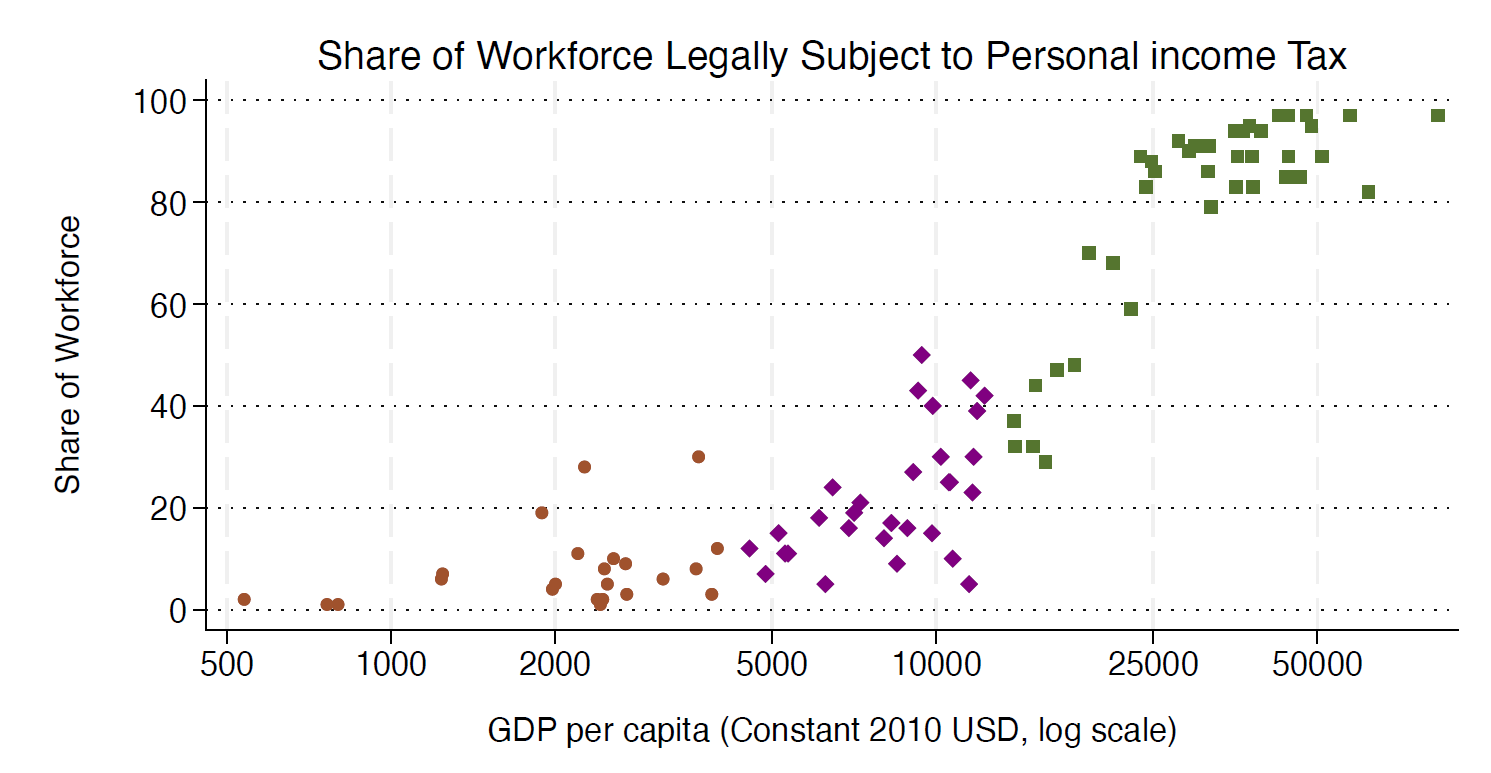

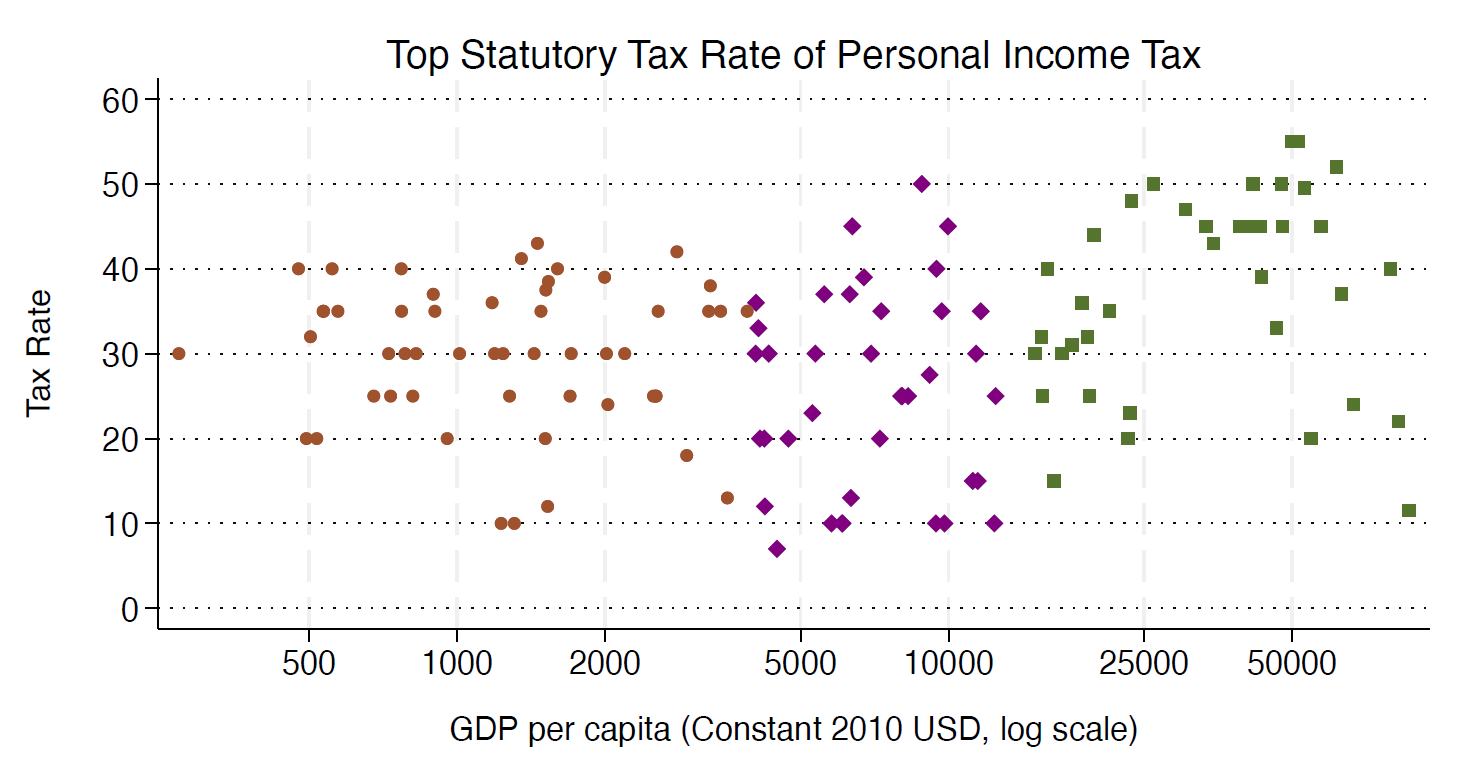

What does the progressivity of personal income taxation look like in practice? While systematic studies on taxes paid by the very richest (e.g. top 1 or 0.1 %) are lacking, household survey data, combined with assumptions on taxes paid by salaried versus self-employed workers, allows for cross-country comparisons of effective income taxes paid by income decile. For methodology details, refer to Commitment to Equity (Lustig 2022), with updated data for 74 countries by the World Bank (2022). In the first panel of Figure 3, the share of household budgets paid in personal income taxes by income decile is plotted across countries categorised by development levels. Some key patterns emerge. The average effective tax rates for income taxes are higher in high-income countries across all deciles of the income distribution, and tax rates for the top deciles increase steeply with development. In high-income countries, the richest 10% pay around 20% of their income in direct taxes, compared to 5-8% in low- and middle-income countries. These disparities partly stem from the shift from informal to formal employment during development, as discussed earlier. The middle panel of Figure 3 illustrates that the proportion of the workforce legally liable for personal income taxes increases significantly with development, primarily affecting only the top deciles in low- and middle-income countries. The bottom panel of Figure 3 shows that the top statutory tax rates are only slightly lower in poorer countries (29% on average) compared to high-income countries (35%). This difference in statutory rates cannot account for the substantial variation in de facto income tax rates observed over development (first panel of Figure 3).

Figure 3

Taxing the rich may be particularly difficult in low- and middle-income countries because of the ample evasion and avoidance opportunities available to high earners, which could lead to large behavioural responses in the form of reductions in reported income when tax rates increase. The size of behavioural responses is typically measured with the elasticity of taxable income, which estimates the percent change in reported income for a 1% change in the “net-of-tax rate” (one minus the tax rate). Only in the last few years has the elasticity of taxable income of rich individuals been estimated in some low- and middle-income countries, thanks to increased collaborations between tax administrations and researchers. In both Uganda and South Africa, increases in the marginal income tax rate for the richest 1% led to large reductions in reported income, with elasticities estimated at just below one, indicating most of the potential increase in tax revenue was lost due to reported incomes being manipulated (Jouste et al. 2021, Axelson et al. 2023). In Uruguay, the elasticity was estimated to be around 0.6 (Bergolo et al. 2022). Studies of capital taxation in low- and middle-income countries similarly find large behavioural responses: in Colombia, the elasticity of reported wealth to the wealth tax rate is estimated at around two, driven by the underreporting of hard-to-verify assets (Londoño-Vélez and Ávila-Mahecha 2022). Changes to reported taxable income can even be sufficiently large that raising top tax rates leads to lower total revenue collection - for evidence from Pakistan, see Waseem (2018); for evidence from Brazil, see Locks (2023).

However, the elasticities of reported income for top earners are not fixed. Instead, they depend on the availability of opportunities for tax evasion and the enforcement capacity of tax administrations. In Colombia, a programme incentivising the voluntary disclosure of hidden wealth in exchange for tax breaks had a significant impact on tax revenues and progressivity (Londoño-Vélez and Ávila-Mahecha 2021). Similarly , Argentina's 2016 tax amnesty revealed assets equivalent to 21% of the country's GDP, with over 80% of these assets previously concealed abroad, primarily in the United States and tax havens (Londoño-Vélez and Tortarolo 2022). In Ecuador, a tax on dividends distributed to shareholders in tax havens prompted income repatriation and enhanced tax progressivity (Brounstein 2023). The success of recent tax amnesties is partly attributed to the introduction, since 2016, of automatic information exchange between tax authorities across borders (Alstadsæter et al. 2023).

Several challenges persist despite recent progress. One critical issue is the exclusion of real estate wealth from international information exchanges. This gap potentially undermines the progressivity of tax systems (Alstadsæter et al. 2022). Moreover, a significant portion of income among the wealthiest individuals stems from business earnings and retained profits, which are inadequately captured by personal income tax systems. Here, corporate income tax serves as a crucial complement, ensuring some taxation of business incomes and bolstering overall tax progressivity (Fuest and Neumeier 2023). However, globally, the effectiveness of corporate taxation as a backstop has diminished, with declining statutory rates and the proliferation of low-tax regimes benefiting large corporations disproportionately (Tørsløv et al. 2023, Johannesen et al. 2020).

References

Alstadsæter, A, N Johannesen, and G Zucman (2018), "Who owns the wealth in tax havens? Macro evidence and implications for global inequality", Journal of Public Economics, 162: 89–100.

Alstadsæter, A, S Godar, P Nicolaides, and G Zucman (2023), "Global Tax Evasion Report 2024", Paris: EU Tax Observatory.

Alstadsæter, A, B Planterose, G Zucman, and A Økland (2022), "Who owns offshore real estate? Evidence from Dubai", EU Tax Observatory Working Paper 1.

Atkinson, A B, and J E Stiglitz (1976), "The design of tax structure: Direct versus indirect taxation", Journal of Public Economics, 6(1–2): 55–75.

Axelson, C, A Hohmann, J Pirttilä, R Raabe, and N Riedel (2023), "What happens when you tax the rich? Evidence from South Africa", Unpublished.

Bachas, P, A Jensen, and L Gadenne (2024), "Tax equity in low- and middle-income countries", Journal of Economic Perspectives, 38(1): 55-80.

Bachas, P, L Gadenne, and A Jensen (2023), "Informality, consumption taxes, and redistribution", Review of Economic Studies, rdad095.

Bergolo, M, G Burdin, M De Rosa, M Giaccobasso, M Leites, and H Rueda (2022), "How do top earners respond to taxation? Evidence from a tax reform in Uruguay", Unpublished.

Bergolo, M, J Londoño-Vélez, and D Tortarolo (2023), "Tax progressivity and taxing the rich in developing countries: Lessons from Latin America", Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 39(3): 530-549.

Brounstein, J (2023), "Can countries unilaterally mitigate tax haven usage? Evidence from Ecuadorian transaction tax data", Unpublished.

Chancel, L, D Cogneau, A Gethin, A Myczkowski, and A S Robilliard (2023), "Income inequality in Africa, 1990–2019: Measurement, patterns, determinants", World Development, 163: 106162.

Fuest, C, and F Neumeier (2023), "Corporate taxation", Annual Review of Economics, 15: 425–450.

Huang, J, and J Rios (2016), "Optimal tax mix with income tax non-compliance", Journal of Public Economics, 144: 52–63.

Johannesen, N, T Tørsløv, and L Wier (2020), "Are less developed countries more exposed to multinational tax avoidance? Method and evidence from micro-data", World Bank Economic Review, 34(4): 790-809.

Jensen, A (2022), "Employment structure and the rise of the modern tax system", American Economic Review, 112(1): 213-234.

Jouste, M, T K Barugahara, J O Ayo, J Pirttilä, and P Rattenhuber (2021), "The effects of personal income tax reform on employees’ taxable income in Uganda", WIDER Working Paper 2021/11.

Kopczuk, W, and E Zwick (2020), "Business incomes at the top", Journal of Economic Perspectives, 34(4): 27-51.

Lagakos, D (2016), "Explaining cross-country productivity differences in retail trade", Journal of Political Economy, 124(2): 579-620.

Locks, G (2023), "Behavioral responses to inheritance taxes: Evidence from Brazil", Unpublished.

Londoño-Vélez, J, and J Ávila-Mahecha (2021), "Enforcing wealth taxes in the developing world: Quasi-experimental evidence from Colombia", American Economic Review: Insights, 3(2): 131-148.

Londoño-Vélez, J, and J Ávila-Mahecha (2022), "Behavioral responses to wealth taxation: Evidence from Colombia", Unpublished.

Londoño-Vélez, J, and D Tortarolo (2022), "Revealing 21 per cent of GDP in hidden assets: Evidence from Argentina’s tax amnesties", WIDER Working Paper 2022/103.

Lustig, N (ed.) (2022), Commitment to equity handbook: Estimating the impact of fiscal policy on inequality and poverty, Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Scheuer, F, and J Slemrod (2021), "Taxing our wealth", Journal of Economic Perspectives, 35(1): 207-230.

Tørsløv, T, L Wier, and G Zucman (2023), "The missing profits of nations", Review of Economic Studies, 90(3): 1499-1534.

Ulyssea, G, M Bobba, and L Gadenne (2024), “Informality”, VoxDevLit, 6.1.

Warren, N (2008), "A review of studies on the distributional impact of consumption taxes in OECD countries", OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Paper 64.

Waseem, M (2018), "Taxes, informality and income shifting: Evidence from a recent Pakistani tax reform", Journal of Public Economics, 157: 41-77.

World Bank (2022), Poverty and shared prosperity correcting course, Washington, DC: World Bank.

Contact VoxDev

If you have questions, feedback, or would like more information about this article, please feel free to reach out to the VoxDev team. We’re here to help with any inquiries and to provide further insights on our research and content.