In India, over 30% of reported rape cases involve victims under 18, with girls particularly at-risk. Legal reforms and cultural shifts are essential, but slow to implement. Could school toilets provide a short-term solution to the problem?

Warning: This article contains references to sexual violence and abuse.

School without adequate sanitation infrastructure pose safety risks for girls

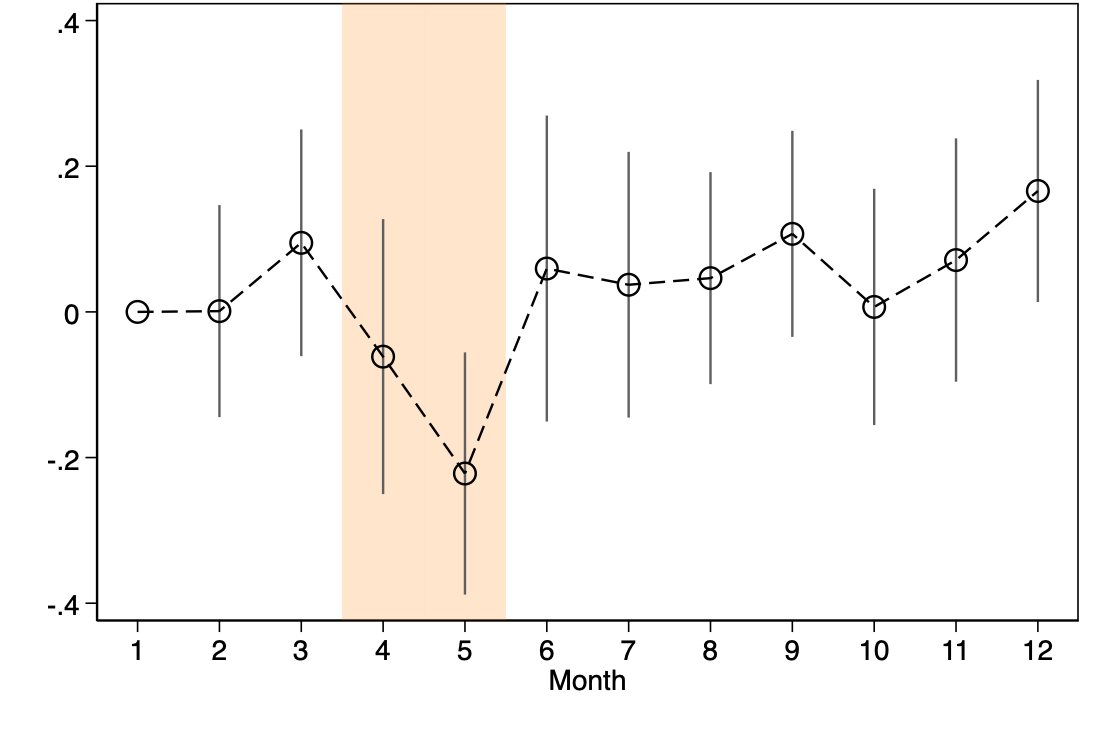

Children spend a significant part of their day at school, a space designed to foster safety and learning. However, evidence suggests that these spaces can sometimes have hidden dangers (Evans et al. 2023). Research on child sex crimes in India highlights the significant prevalence of abuse within school environments (Choudhry et al. 2018). Monthly data on child sexual violence from Karnataka shows that these cases decreased by 20% during April and May, coinciding with school holidays for primary and secondary schools in the state (Figure 1). This seasonal pattern—which indicates that incidents of child rape rise during academic semesters and fall during school holidays—suggests that schools can be unsafe environments for children.

Figure 1: Seasonality of child sexual abuse cases

Note: This graph shows how child sexual abuse cases in Karnataka change throughout the year, based on monthly data from 2021 and 2022. Karnataka was the only state in which we could obtain this detailed information.

Inadequate sanitation facilities play a major role in exacerbating the problem. In 2020, an incident in Gujarat brought this issue into media spotlight again, in which a schoolgirl was raped while looking for a private place to relieve herself near her school (Times of India 2020). Despite the state being declared ‘open defecation free’, the absence of usable toilets left her exposed to harm. This is far from an isolated case; 22% of schools in India lack proper facilities for girls, and a quarter of girls miss classes during menstruation in schools that lack sex-specific toilets (UNICEF 2024).

Without proper toilets—many of which lack doors and walls—girls are forced to make difficult decisions, including risking open defecation, limiting their water intake, or missing school during menstruation (Thatipalli 2024). Providing separate toilets for boys and girls can enhance safety for girls in two critical ways.First, it reduces open defecation by offering a private, secure space, minimising girls' exposure to potential attackers. Second, in co-ed schools, since the risk often comes from within, sex-specific sanitation facilities create a physical barrier between males and females, reducing the possibility of harassment and abuse.

Building sex-specific toilets reduces child sexual abuse in schools

While the health and educational benefits of school sanitation are well-documented (Cameron et al. 2019, Adukia 2017), its effect on gendered crime remains underexplored. Our research is the first to provide evidence on how constructing separate toilets for girls in schools significantly reduces child rape cases in India (Gao et al. 2025). Specifically, we find that not all types of school toilets have the same deterrent effect: only sex-specific toilets effectively deter such behaviours, particularly in co-educational and secondary schools, whereas unisex toilets do not.

The high risk of sexual crimes associated with open defecation has long been a concern in India, with most research focusing on in-home toilets and adult women as victims (Hossain et al. 2022); however, there is a lack of evidence on school environments and child victims. We analysed data from 600 Indian districts between 2005 and 2012, a period before legal changes confounded crime statistics. Using a combination of school toilet records and crime data, we found that a 10% increase in female students having access to sex-specific toilets reduces child rape cases by 2.6%. Furthermore, our findings reveal that this effect is mainly driven by toilets built in co-ed schools, where perpetrators are likely male students or staff, and in secondary schools, where students aged 13-18 are most at-risk to sexual crimes. In contrast, unisex toilets fail to offer the same protective benefits, at least in India.

Validating the causal relationship between school toilets and sexual abuse

We examine potential confounding factors and work to establish causality regarding whether school toilets reduce sexual crimes against children. Our analysis shows that the impact of school toilets isn’t driven by factors such as economic prosperity, legal or policing capacity, or other school infrastructure. Placebo tests further reveal that constructing school toilets has no impact on other sexual crimes (e.g. adult rape, other gender-related crimes), suggesting that the reduction in child rape can be specifically attributed to school toilets, as opposed to improved policing or other broader societal changes that generally reduce crime.

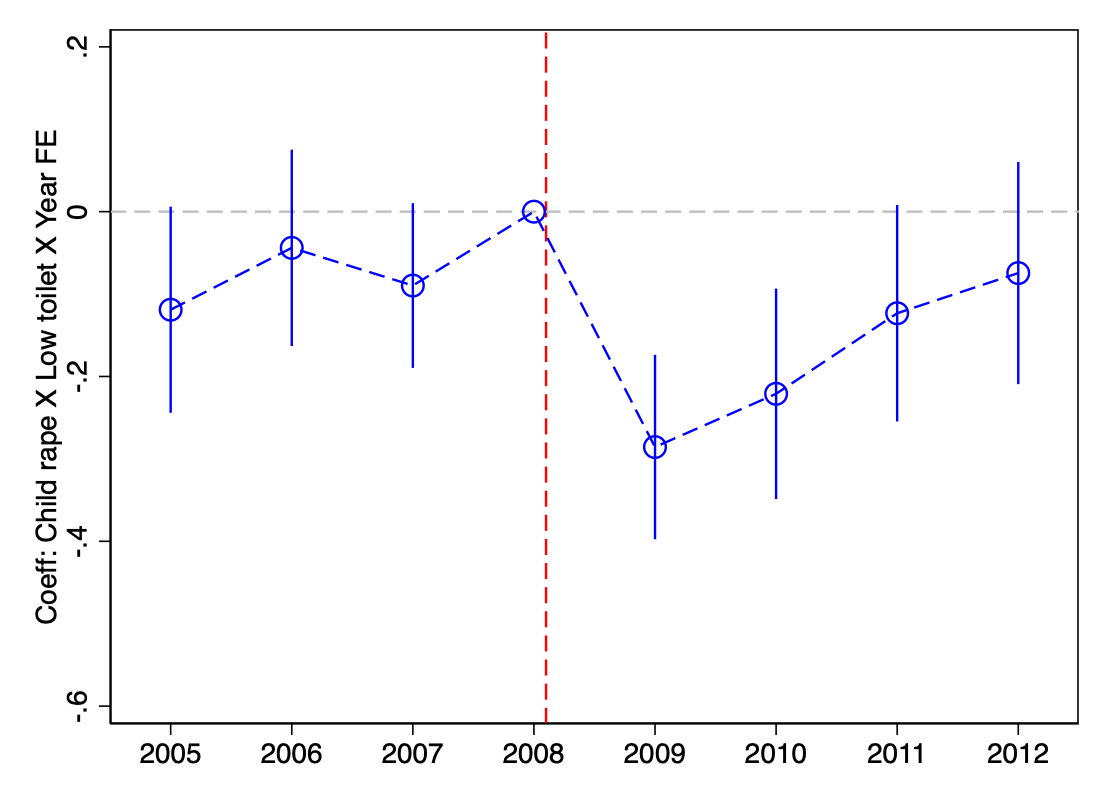

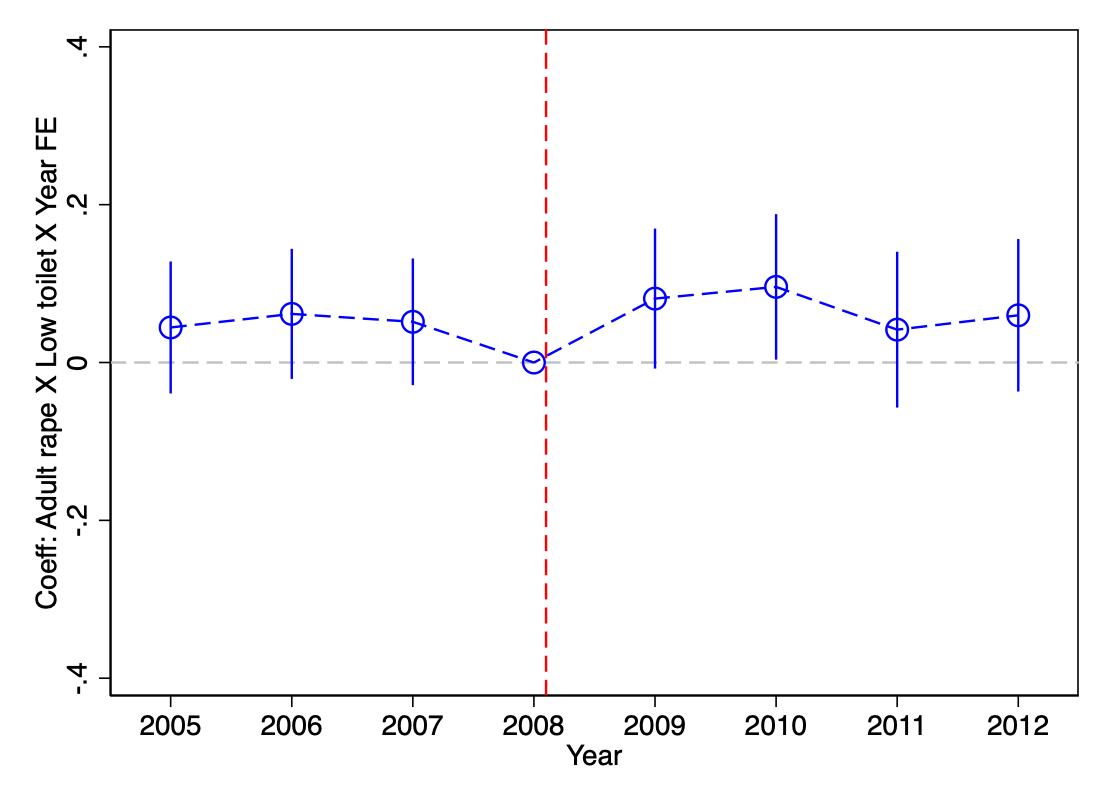

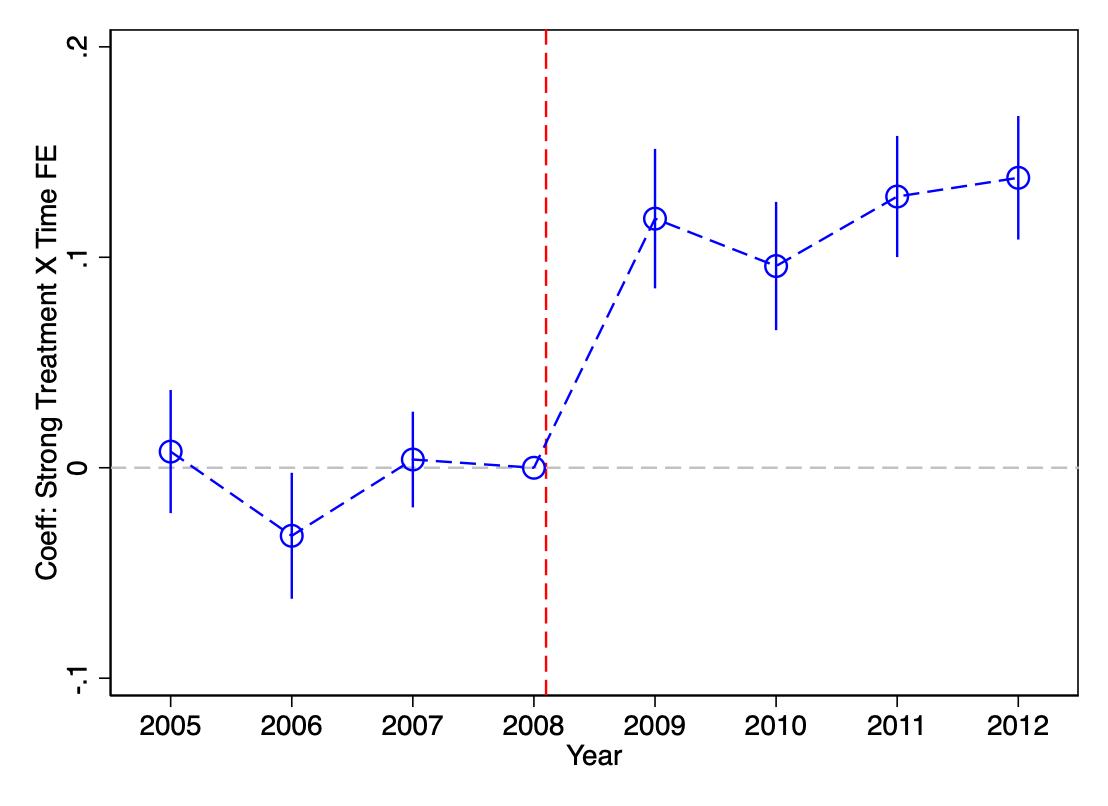

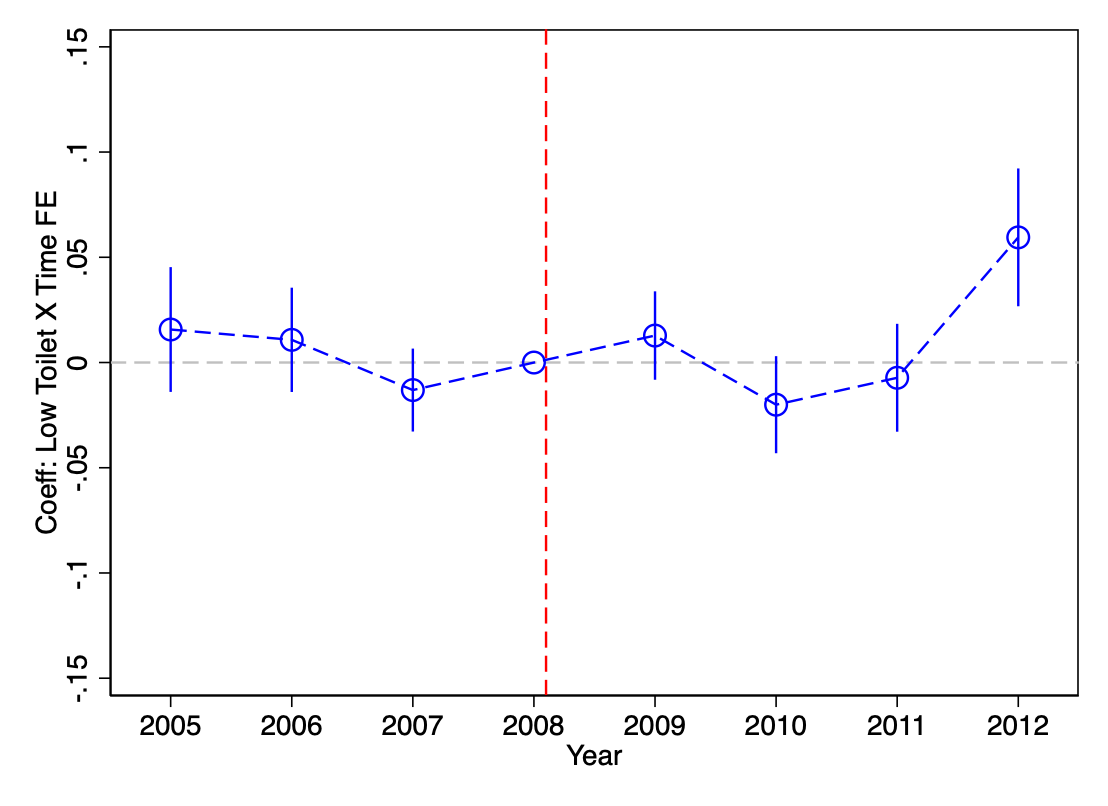

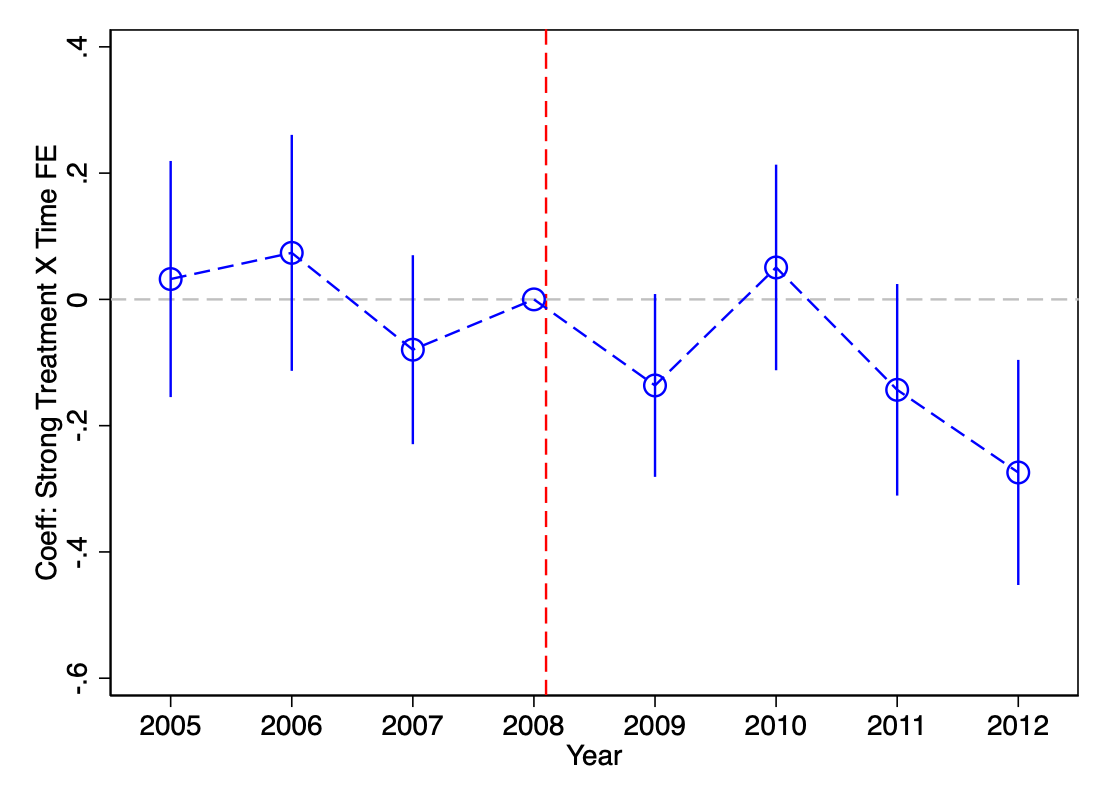

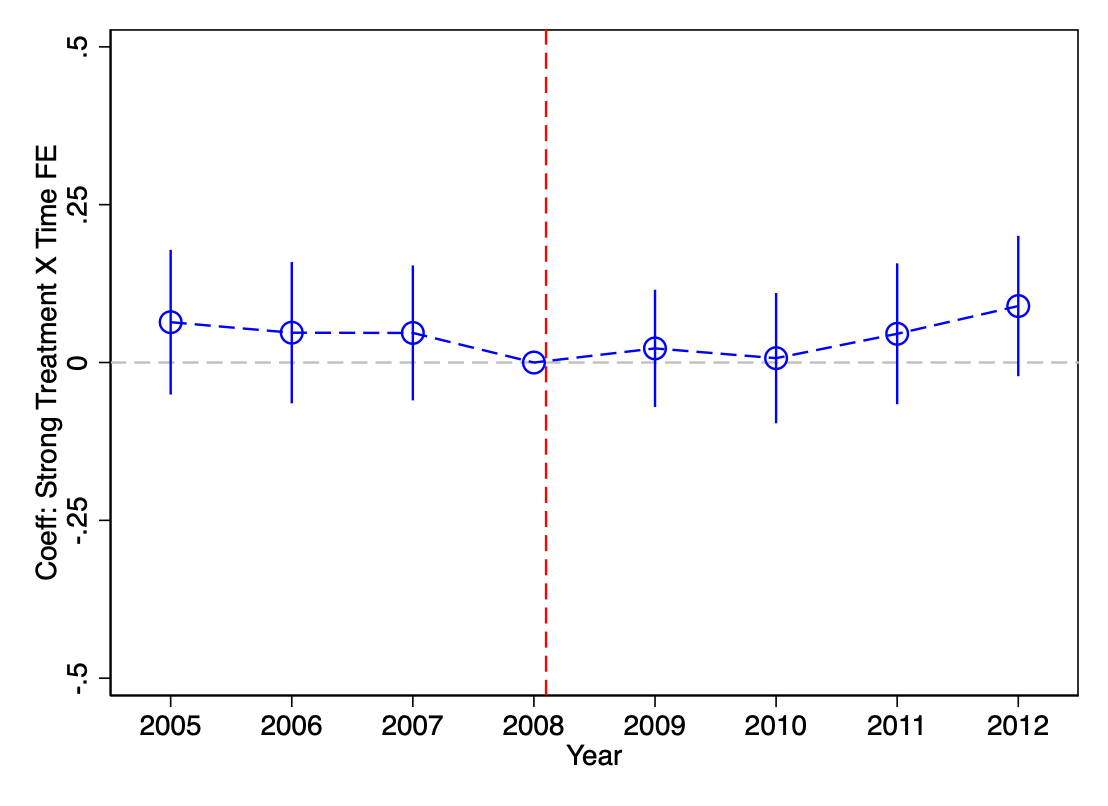

To further assess causality, we also analyse a toilet construction surge following the 2009 Right to Education Act and Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan scheme, which mandated toilet blocks as a minimum school standard to promote basic sanitation. Figure 2 Panel A shows a significant rise in toilet construction post-2009 in districts with initially low toilet coverage, confirming the policy’s impact, while Panel B indicates no corresponding increase in other school infrastructure, such as school walls. Panel C reveals a drop in child rape cases in strong treatment districts after 2009, while Panel D shows adult rape cases remained stable. Panels E and F use a triple-difference approach—comparing child rape to other crimes, low- versus high-toilet-coverage districts, and pre- versus post-2009 periods—validating our findings. This also ruled out the possibility that underreporting was driving our results, as it is unlikely that only the reporting of child rape cases changed in low-toilet coverage districts post 2009.

Figure 2: The impact of 2009 educational schemes

Panel A: School toilet coverage Panel B: School wall

Panel C: Child rape cases (DID) Panel D: Adult rape cases (DID)

Panel E: Child rape cases (DDD) Panel F: Adult rape cases (DDD)

The effects are more pronounced in districts with more equitable gender attitudes

Physical barriers alone are not enough. Social psychology research suggests that for sexual violence to occur, perpetrators must overcome two key barriers: (1) external obstacles to access, and (2) their own internal inhibitions (Rudolph et al. 2018). Sex-specific toilets can help tackle the former, but cultural norms shape the latter. Harmful gender norms can legitimise sexual violence against girls, increasing the likelihood of such crimes (Know Violence in Childhood 2017), thereby weakening the effects of school toilet provision.

To examine the role of local culture, we investigate whether the effects of toilet construction depend on local gender norms. Our findings reveal that in districts with more equitable gender attitudes—fewer child brides, lower tolerance for wife beating, less skewed birth sex ratios—sex-specific school toilets exerted a stronger impact. Where detrimental norms endure, the protective role of school toilets against sexual crimes diminished.

Implications for school infrastructure policy

Our findings demonstrate that school toilets are more than just infrastructure—they are also a shield against sexual violence. However, success of this policy depends on toilet type, school setting, and local culture. Policymakers should hence prioritise sex-specific toilets in co-ed and secondary schools where the risks of sexual violence are the highest. Construction alone will not suffice; long-term success depends on tackling gender norms. In a country where millions of girls lack basic protections, this dual approach could help make schools real sanctuaries.

References

Adukia, A (2017), “Sanitation and education,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 9(2): 23–59.

Cameron, L, S Olivia, and M Shah (2019), “Scaling up sanitation: Evidence from an RCT in Indonesia,” Journal of Development Economics, 138: 1–16.

Choudhry, V, R Dayal, D Pillai, A S Kalokhe, K Beier, and V Patel (2018), “Child sexual abuse in India: A systematic review,” PLOS ONE, 13(10): e0205086.

Evans, D K, S Hares, P A Holland, and A Mendez Acosta (2023), “Adolescent girls’ safety in and out of school: Evidence on physical and sexual violence from across sub-Saharan Africa,” The Journal of Development Studies, 59(5): 739–757.

Gao, P, A Kothari, and Y H Lei (2025), “Safe spaces for children: School sanitation and sexual violence,” European Economic Review, 172: 104952.

Hossain, M A, K Mahajan, and S Sekhri (2022), “Access to toilets and violence against women,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 114: 102695.

Know Violence in Childhood (2017), "Ending violence in childhood: Global report 2017."

Rudolph, J, M J Zimmer-Gembeck, D C Shanley, and R Hawkins (2018), “Child sexual abuse prevention opportunities: Parenting, programs, and the reduction of risk,” Child Maltreatment, 23(1): 96–106.

Thatipalli, M (2024), “Loo and she can’t behold,” The New Indian Express.

Times of India (2020), “Ahmedabad: Girl relieving herself in the open raped,” Times of India.

UNICEF (2024), “Clean India - Clean schools.”