A governmental employment-guarantee programme designed to provide economic security to rural households in India has unintentionally reduced women’s labour force participation—deepening gender disparities within households. By guaranteeing employment, the policy replaces women as ‘added workers’, weakening their financial autonomy and bargaining power. While household consumption rises, women lose economic independence, leading to lower resource control and even declines in well-being. This research discusses how a policy aimed at poverty alleviation may inadvertently reinforce existing gender inequalities.

Editor’s note: For a broader synthesis of themes covered in this article, check out our VoxDevLit on Female Labour Force Participation.

Women’s participation in the labour market is a key determinant of their financial autonomy and bargaining power within households; it shapes their relationship with their husbands and how much of the total household resources they get to consume. Research in labour and development economics establishes that when women earn income, they gain more significant influence over household decisions, leading to improved well-being and investment in children’s education and health (Kessler-Harris 2003, Sen 1990). However, in many parts of the world, female labour force participation remains low, shaped by structural constraints, economic incentives, and gender norms (Jayachandran 2021).

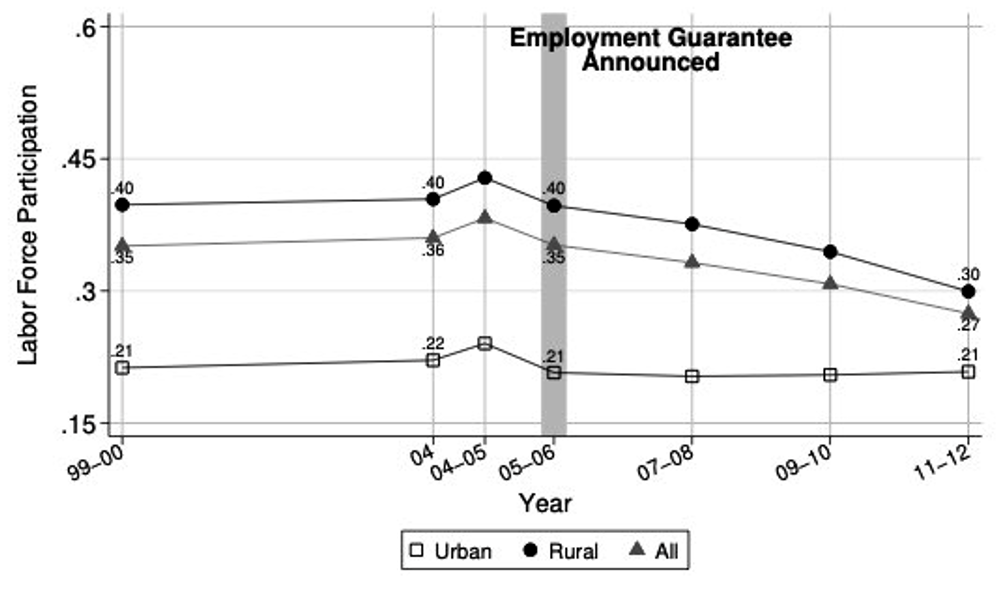

India is a salient example of this global challenge. Over the last three decades, rural female labour force participation has declined significantly, falling from already low levels. Between 2005 and 2012 alone, the participation rate for rural married women dropped from 40% to 30% despite India experiencing sustained economic growth over this period (World Bank 2022).

Figure 1. Female labour force participation in India

In my research (García 2025), I investigate the role of India’s employment guarantee, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, in shaping labour market outcomes and the allocation of resources within the household. This flagship policy, announced in 2005 and rolled out nationally between 2006 and 2008, guarantees up to 100 days of paid employment per year per household for individuals willing to work in governmentally run construction job sites. The policy is primarily designed to enhance economic security and reduce rural poverty. It also aims to empower women by providing them with jobs.

My research finds that the employment guarantee unintentionally crowds out rural married women from the labour force. By providing a stable source of earnings for households, the programme reduces the need for women to act as ‘insurance’ workers in times of economic uncertainty. In India, rural women participate in the labour force mainly as insurance workers. Indeed, their families prefer that they do not work at all, if economically viable, due to cultural norms. The employment guarantee directly competes with them as an alternative source of insurance and crowds them out. This result is reinforced by the referred cultural norms. My findings have implications for women’s financial autonomy, household decision-making, and broader patterns of labour market participation.

Why a guaranteed employment policy may reduce female work

At first glance, the employment guarantee appears to promote women’s labour market engagement. The law explicitly mandates that women hold at least one-third of jobs. In practice, women’s participation in the programme has been high: between 2012 and 2021, 54% of all programme jobs were held by women, amounting to 44 million women working at least one job day per year (Government of India 2022).

However, this participation statistic does not necessarily mean that the programme increased women’s overall employment. Many women who work in employment-guarantee jobs may have shifted from other forms of employment rather than entering the labour force for the first time. More importantly, by reducing household financial uncertainty, the policy may have inadvertently weakened a key driver of female labour force participation: the need for women to work as a buffer against household income shocks.

This is especially true in low-income households, which are the policy’s main target, women serve as ‘added’ or ‘insurance’ workers—stepping into the labour market when primary earners (usually men) experience income instability. This is crucial in rural areas, where agricultural work is seasonal, wages are volatile, and formal insurance is limited (Alik-Lagrange and Ravallion 2018). When a government programme like the employment guarantee provides a predictable income stream, it reduces the need for this secondary income source, leading to fewer women participating in the labour force.

Measuring the impact of guaranteed employment on female employment

To examine the impact of the employment guarantee on female labour force participation, I use a nationally representative sample from the Employment and Unemployment National Sample Survey, spanning 1999-2012. By leveraging district-level variation in programme rollout and state-level variation in intensity, I find the following:

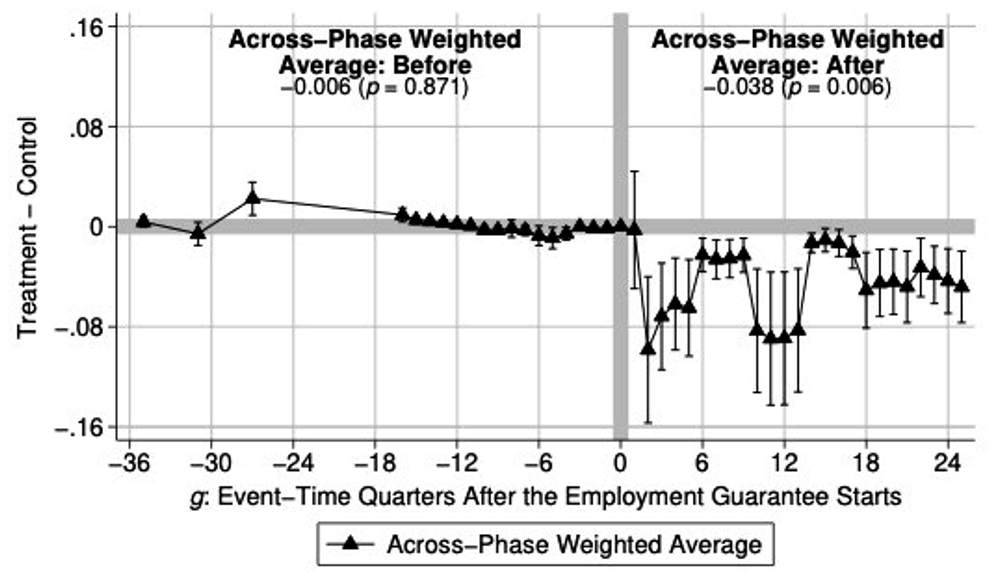

- Rural married women’s labour force participation decreased by four percentage points due to the employment guarantee.

Figure 2. Impact on rural female labour force participation

- This decline is net of participation in programme jobs, meaning the reduction is not just a shift from other jobs into the programme.

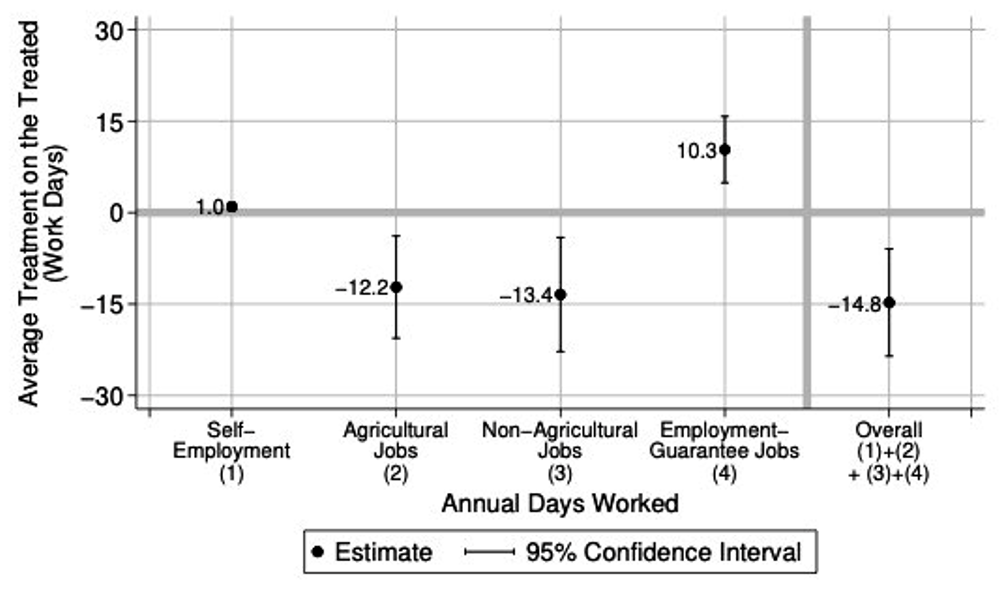

Figure 3. Impact on rural female annual days worked by activity

- When accounting for population weights, the employment guarantee explains up to 30% of the nationwide decline in rural female labour force participation during the study period.

These results are robust across multiple datasets. Using data from the Indian Human Development Survey (IHDS), which allows for longitudinal tracking of individuals, I confirm that the employment guarantee leads to the same pattern of decline in female labour force participation. Crucially, men’s labour force participation remains unaffected at the extensive margin—men do not reduce their participation in the workforce, though they reduce their total annual workdays.

Does the employment guarantee improve economic security?

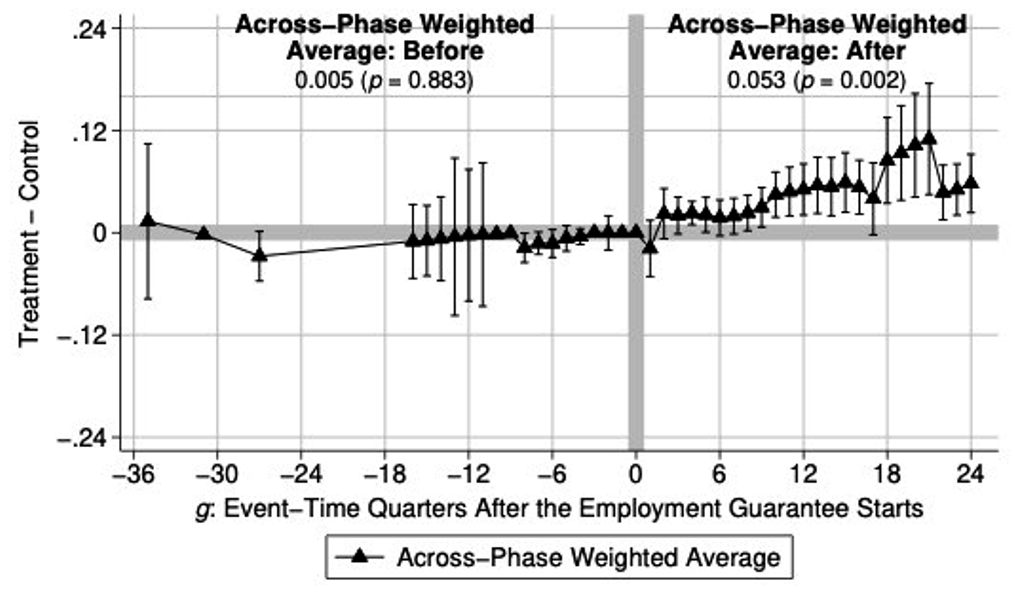

The employment guarantee succeeds in providing economic security to rural households. Using the same empirical framework, I find that the programme increases monthly household consumption per capita by 5% to 7%, from a baseline average of US$244 (2018 purchasing power parity). By providing a stable source of income, the policy reduces absolute poverty at the household level.

Figure 4. Impact on household consumption

The programme also reduces household savings. Households in the sample experience a drop in per-period savings of $99.6 from a baseline of $237.5 (2018 purchasing power parity). Additionally, there is a small but significant decline in the ownership of physical assets. This suggests that the programme helps families smooth consumption and reduces the need for precautionary savings. This is partly why, while not quitting the labour force, men also reduce their annual days worked.

The hidden costs of guaranteed employment on women’s bargaining power and well-being

Beyond its effects on employment, the guarantee affects women’s bargaining power within households. Since married women’s labour force participation declines, their contribution to total household income shrinks. Using a collective household model (Chiappori 1988), I estimate that the programme reduces women’s intra-household share of resources by 9% from a baseline of 45%.

This reduction in women’s financial autonomy has measurable consequences. A domestic independence index constructed using IHDS data indicates that the programme reduces women’s domestic independence by one-third of a standard deviation. This result aligns with existing research showing that declines in female bargaining power increase domestic constraints and raise the risk of intimate partner violence (Anderson 2021).

Additionally, I find a significant decline in women’s body mass index (BMI), a commonly used proxy for intra-household resource allocation (e.g. Calvi 2020). Since BMI reflects both mental and physical health outcomes (Ackerson and Subramanian 2008, Selvamani and Singh 2018), this suggests that the decline in bargaining power may be harming women’s overall well-being.

Policy implications for strengthening women’s economic autonomy

My findings indicate that, while the employment guarantee achieves its primary goal of economic security, its effects on female empowerment are not positive. Rather than increasing women’s financial independence, it reduces their control over household resources.

To ensure that employment-guarantee schemes enhance, rather than limit, women’s labour force participation, policymakers could consider targeting employment guarantees for individuals, as opposed to households, as found effective in increasing female labour force participation by Field et al. (2021).

India’s employment guarantee has successfully improved economic security for millions of households. However, the unintended consequences on reducing female labour force participation and bargaining power highlights the need for a more nuanced approach to employment policy.

References

Alik-Lagrange, A, and M Ravallion (2018), “Workfare versus welfare: Incentives and trade-offs,” Journal of Development Economics, 134: 121–137.

Ackerson, L K, and S Subramanian (2008), “Domestic violence and chronic malnutrition among women and children in India,” American Journal of Epidemiology, 167(10): 1188–1196.

Anderson, S (2021), “Intimate partner violence and female property rights,” Nature Human Behaviour, 5(8): 1021–1026.

Calvi, R (2020), “Why are older women missing in India? The age profile of bargaining power and poverty,” Journal of Political Economy, 128(7): 2453–2501.

Chiappori, P-A (1988), “Rational household labor supply,” Econometrica, 56(1): 63–90.

Field, E, R Pande, N Rigol, S Schaner, and C Troyer Moore (2021), “On her own account: How strengthening women’s financial control impacts labor supply and gender norms,” American Economic Review, 111(7): 2342–2375.

García, J L (2025), “Guaranteed employment in rural India: Intra-household labor and resource allocation consequences,” Unpublished manuscript.

Government of India (2022), "Open government data platform India".

Jayachandran, S (2021), “Social norms as a barrier to women’s employment in developing countries,” IMF Economic Review, 69(3): 576–595.

Kessler-Harris, A (2003), "In pursuit of equity: Women, men, and the quest for economic citizenship in 20th-century America", Oxford University Press.

Selvamani, Y, and P Singh (2018), “Socioeconomic patterns of underweight and its association with self-rated health, cognition, and quality of life among older adults in India,” PLOS ONE, 13(3).

Sen, A (1990), “Gender and cooperative conflicts,” in A Sen and I Tinker (eds.), Persistent inequalities, Oxford University Press, 235–297.

World Bank (2022), "Female labor force participation rate", World Bank.