Unregulated markets for second-hand goods fuel crime worldwide. In Brazil, strengthening oversight of the second-hand market for automotive parts helped reduce car theft, simultaneously lowering insurance prices.

Editor’s note: For a broader synthesis of themes covered in this article, check out our VoxDevLit on Informality.

Around the world, unregulated markets for second-hand goods fuel crime. Stolen smartphones, bicycles, automotive parts, and electronics are being traded in informal resale channels, creating incentives for robbery and theft (Kirchmaier et al. 2020, d’Este 2020, WHO 2024, ICG 2022, EUIPO 2024). Governments usually address this problem in the short term by increasing police presence, given the extensive evidence of its effectiveness in preventing robbery and theft (Chalfin and McCrary 2017, Levitt 2002, Evans and Owens 2007). However, what else can be done to reduce property crime and address the underlying demand for stolen goods? In this context, Brazil's regulation of junkyards and the market for auto parts provides compelling evidence on how the use of technology for the target of illegal trade can reduce crime.

The policy intervention: A crackdown on junkyards

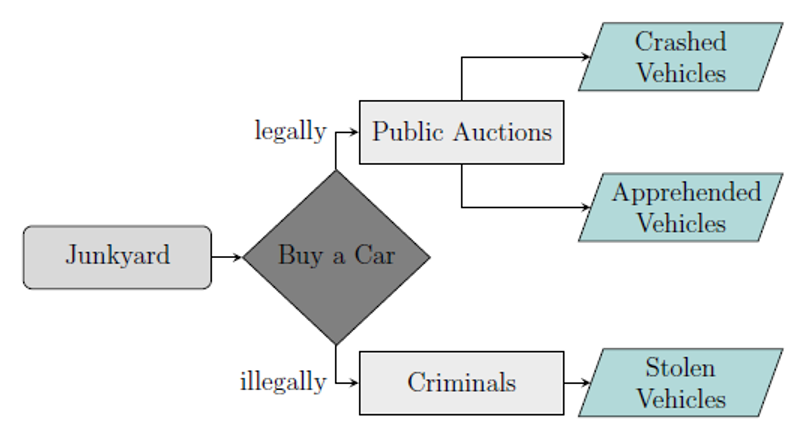

Recognising that auto theft was driven largely by demand for cheap and unverified spare parts, the state of São Paulo, Brazil, introduced a regulation to increase control and transparency. Junkyards are suppliers of second-hand spare parts and account for approximately 10% of the market, according to industry estimates. Although the trade of used parts is legal in Brazil, in an environment with weak supervision, it is difficult to track the source of automotive parts sold by junkyards. Figure 1 shows the possible channels by which junkyards acquire spare parts: auctions of destroyed and seized vehicles organised by the state, or access to the illegal market for stolen cars.

Figure 1: Channels by which junkyards acquire cars and parts

Source: Mancha (2025).

The regulation implemented in 2014 required junkyards to register, maintain inventory records, and comply with new reporting requirements. In particular, junkyards selling used car parts must include a link to the government website where it is possible to verify whether the vehicle the part came from was purchased at a public auction. If the link does not exist, it is assumed that the part came from the illegal market, subjecting the owner of the junkyard to a legal sanction ranging from a fine to the closure of the store. Figure 2 provides an example of a QR code linking to the government website that became compulsory after the regulation. With the help of a mobile phone, authorities and consumers can verify whether spare parts have been legally purchased. By making it harder to sell stolen parts, the regulation sought to increase the costs of illegal trade and disrupt criminal supply chains.

Figure 2: QR code providing registration information for auto parts

Source: Mancha (2025).

Increased supervision of junkyards reduced auto theft

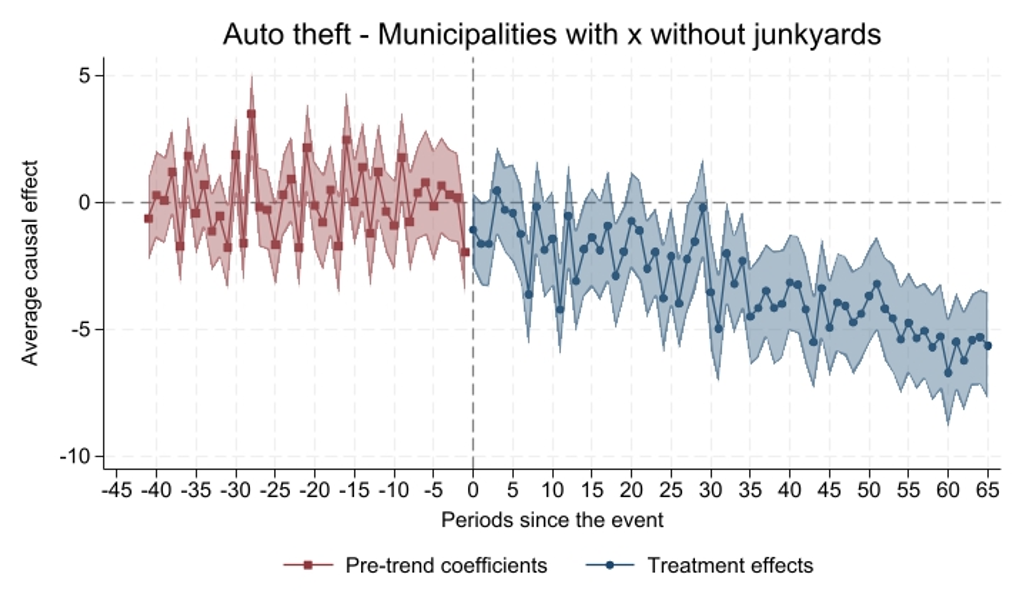

Although the market regulation was implemented in the whole state simultaneously, in Mancha (2025), I explore the distribution of junkyards across municipalities of São Paulo to assess the effect of harsher supervision in the market for auto parts. The regulation imposed several restrictions on the trade of unregistered auto parts; therefore, municipalities with a substantial presence of junkyards would be arguably more affected than the ones with none. Figure 3 shows the effect of the market regulation on auto theft. The drop in stolen vehicles for municipalities with junkyards is equivalent to 8.11% fewer stolen vehicles per month compared to the control group.

Figure 3: Auto theft in municipalities with vs. without junkyards

Source: Mancha (2025).

Notably, this reduction was not followed by increases in other types of property crime, suggesting that the regulation did not simply shift criminal activity elsewhere. The findings indicate that when stolen goods become harder to sell, the incentives for theft decrease.

To assess further economic benefits of the regulation, I investigate if the reduction in auto theft was translated into lower insurance prices for vehicles. Although I cannot address the role of the increased competition between insurance companies, my analysis shows a 15.97% decrease in the insurance premium in municipalities with junkyards after implementing the policy, which was not driven by a reduction in the number of insurance contracts, suggesting an additional economic benefit brought on by the regulation.

Figure 4: Insurance prices in municipalities with vs. without junkyards

Source: Mancha (2025).

Broader implications for crime policy

The lessons from Brazil extend beyond auto theft. Many types of crime are sustained by the ability to convert stolen goods into money. Regulating secondary markets—such as pawn shops, electronic repair businesses, and scrap metal yards—could similarly reduce incentives for theft and burglary worldwide. Policymakers should consider a multi-pronged approach that leverages technology to monitor this business and combines targeted regulation with traditional law enforcement strategies.

Brazil’s experience underscores the power of addressing the economic underpinnings of criminal activity. By disrupting illicit trade networks, governments can sustainably reduce crime. For countries grappling with high rates of property crime, Brazil’s junkyard regulation provides a valuable model for designing policies that strike at the root causes of theft and illegal resale markets.

References

Chalfin, A, and J McCrary (2017), “Criminal deterrence: A review of the literature,” Journal of Economic Literature, 55(1): 5–48.

d’Este, R (2020), “The effects of stolen-goods markets on crime: Pawnshops, property theft, and the gold rush of the 2000s,” Journal of Law and Economics, 63(3): 449–472.

EUIPO (2024), “Economic impact of counterfeiting in the clothing, cosmetics, and toy sectors in the EU,” European Union Intellectual Property Office.

Evans, W N, and E G Owens (2007), “Cops and crime,” Journal of Public Economics, 91(1–2): 181–201.

ICG (2022), “Keeping oil from the fire: Tackling Mexico’s fuel theft racket,” International Crisis Group.

Kirchmaier, T, S Machin, M Sandi, and R Witt (2020), “Prices, policing and policy: The dynamics of crime booms and busts,” Journal of the European Economic Association, 18: 1040–1077.

Levitt, S D (2002), “Using electoral cycles in police hiring to estimate the effects of police on crime: Reply,” American Economic Review, 92(4): 1244–1250.

Mancha, A (2025), “Dismantling a market for stolen goods: Evidence from the regulation of junkyards in Brazil,” Journal of Development Economics, 103497.

WHO (2024), “Combatting illicit trade,” World Health Organization.