Many businesses in developing countries hire workers from family networks. How does redistributive pressure from family influence hiring decisions? And how do these hiring decisions affect business profits?

Editor’s note: For a broader synthesis of themes covered in this article, check out our VoxDevLit on Barriers to Search and Hiring in Urban Labour Markets.

The prevalence of family hiring

In low-income countries, employers in urban and rural areas often rely on family networks as a source of labour (Chandrasekhar et al. 2020, Jayachandran 2021). Often economists attribute this to employers finding it advantageous to hire relatives because of other frictions in the labour market. For instance, employers may have more information about relatives’ work ethic or ability, than non-related potential employees. In addition, employers may trust that related workers will work hard even if they are not monitored, as related employees are likelier to care about their relatives’ business success.

In my research (Swanson 2025), I explore whether redistributive pressure may also contribute toward the prevalence of family firms. I suggest that, in some cases, employers may face significant pressure to offer financial assistance to extended family members in the form of employment. In addition, I argue that this pressure may come at a cost for employers. Since employers have few relatives, the aptitude of relatives may be lower than the full pool of jobseekers. In addition, managing family may be particularly difficult for employers due to the complexity of terminating or punishing related employees, which may, in turn, make it difficult to motivate related employees.

This theory aligns with a growing body of evidence on redistributive pressure in low- and middle-income countries, where individuals often face social obligations to share income with their kinship networks (Jakiela and Ozier 2016, Carranza et al. 2022, Squires 2024, Riley 2021), as well as a recent strand of research that suggests that work in low-income countries serves a redistributive purpose (Macchi and Stalder 2023). My research builds on this work by showing that the ‘kinship tax’ may also extend to the employment margin, and that when work serves a redistributive purpose, it may have costs for employers.

Studying the impact of social pressure on hiring decisions and productivity

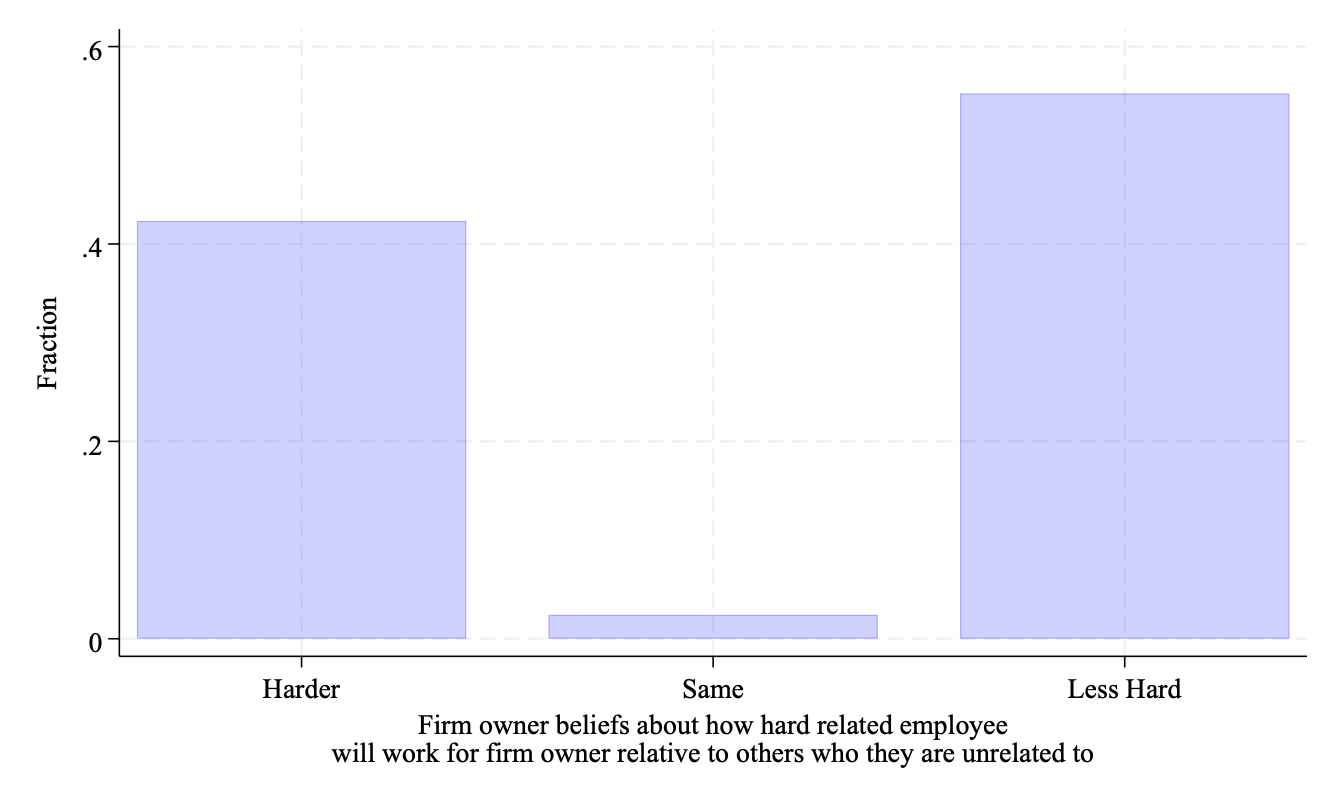

In my research, I focus on a sample of small businesses located in Eastern Province, Zambia, in both the largest urban centre, as well as employers working in the agricultural sector. I document several motivating facts in these samples. First, almost half of employees in the urban sample are related to the employer. Second, hiring family is not costless: in the urban sample I find that related and unrelated employees earn similar wages. Finally, I find evidence that hiring from family may not be desirable. Half of employers say that related workers work less hard than unrelated workers (Figure 1). More than half of employers say that they have felt pressure to give a job to a relative, even if the person was not best suited to the job.

Figure 1: Baseline beliefs of relative versus non-relative employee motivation

Measuring the impact of social pressure using a randomised controlled trial

Guided by these facts, I assess whether pressure from the family leads employers to hire workers they otherwise would not hire. To test this hypothesis, I conducted a series of experiments in which I recruit a sample of firms and offered them a subsidy to hire an additional worker. I then randomise whether these employers have ‘plausible deniability’ for not hiring a related worker.

To do this, I provide employers with two different posters to put up at their business after receiving the subsidy and observe how each poster influences who they hire for the job. While employers in the control group received a poster stating they had full control over who to hire, those in the treatment group received a ‘plausible deniability’ poster suggesting some employers receiving the subsidy did not have control over who they hired, offering a potential excuse against hiring from the family.

I then observed how employers in each group decided who to hire. After making their hiring decision, some employers received a subsidy, while others received a take it or leave it subsidy for the related or unrelated worker.

Plausible deniability has a significant positive impact on hiring and productivity

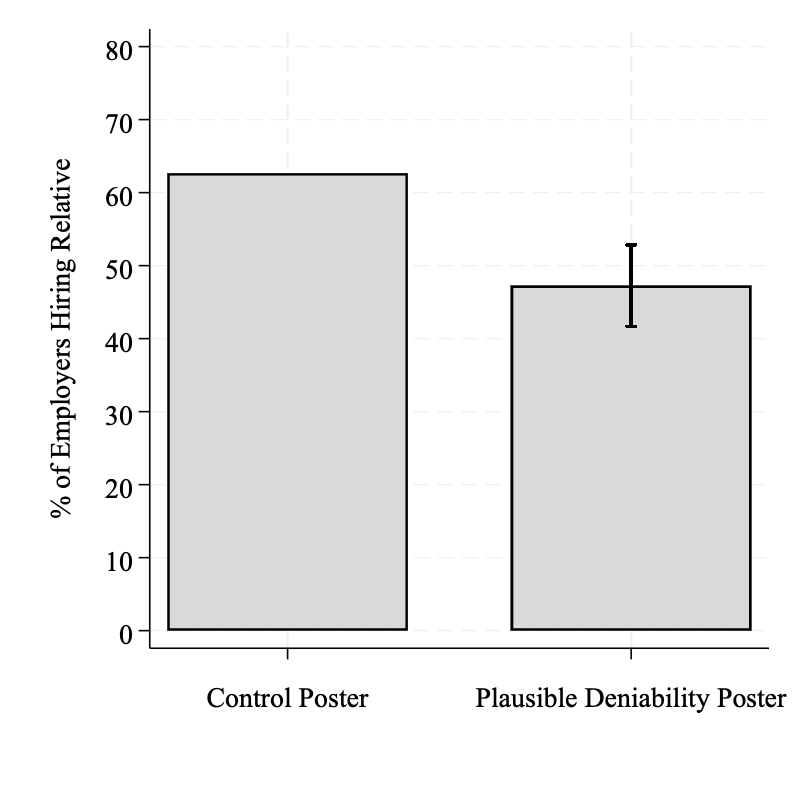

In my experiments, I find several pieces of evidence consistent with employers facing pressure to redistribute jobs to family members. In the urban sample of employers, employers who received the plausible deniability poster were 25% less likely to hire a family member (Figure 2). This suggests that when given an ‘out’, many employers prefer to hire non-relatives. This effect was concentrated among employers stating that they would face sanctions from family for not offering them help when needed, consistent with a pressure cost contributing to the choice.

Figure 2: Employer probability of hiring relatives in control versus treatment groups

In addition, I quantify how costly it is for employers to refuse to hire from their family. On average, I find that this pressure corresponds to 4% of employers’ monthly profits. This is significant and suggests that employers would rather hire an employee from their family than hire an unrelated employee who earns them 4% more profits because of perceived sanctions from the family.

To measure the returns to hiring related and unrelated workers, in the rural sample I randomise employers to receive a subsidy either for a related or unrelated worker. I find evidence consistent with employers having a lower return to hiring related workers. Related hires produced 7% less output for the same cost as unrelated employers. Interestingly, in this task, it appears that this effect is driven by related workers’ shirking rather than being intrinsically less able: when working for piece rates paid by the researcher (rather than their relative), there was no productivity difference between related and unrelated workers. Altogether, this suggests that hiring pressure can have meaningful negative impacts on business productivity.

Given the apparent economic inefficiency of this arrangement, one might wonder why this pressure persists? In my experiments and using supplementary data, I identify two key frictions that may contribute to its persistence. First, pressure to hire seems to be more problematic in jobs where employees can easily make excuses for poor performance. In such roles, employees can slack off without the employer being able to definitively prove their lack of effort to family members, making it challenging to terminate their employment. Second, I document that there appears to be a divergence in beliefs between employers and their relatives regarding the productivity of family hires. Employers tend to anticipate lower productivity from related workers, contrary to the perceptions of family members. This disparity may lead to a discrepancy in hiring preferences between family members and employers, further perpetuating the pressure to hire relatives despite potential economic drawbacks.

Implications of hiring family on social insurance policy

A substantial body of evidence in development has explored frictions in labour markets, often attributing limited and network-based hiring to information and contracting constraints. In response, policymakers have implemented various active labour market policies to address these issues.

My research, however, proposes an alternative explanation for these labour market characteristics. In line with recent studies, my findings suggest that employment serves a redistributive function, while also highlighting potential costs for employers. If the pressure to hire relatives stems from labour markets with high unemployment and limited opportunities, this implies that social insurance policies or other mechanisms of family support can enhance firm productivity by alleviating the burden on employers to assist their relatives.

My findings offer new insights into the dynamics of labour markets in low-income countries and suggest that addressing the underlying causes of redistributive pressure could lead to more efficient hiring practices and improved business outcomes. Policymakers should consider broadening their focus beyond traditional labour market interventions to include measures that provide alternative means of family support, potentially yielding benefits for both employers and job seekers.

References

Carranza, E, A Donald, F Grosset, and S Kaur (2022), “The social tax: Redistributive pressure and labor supply,” Unpublished manuscript.

Chandrasekhar, A G, M Morten, and A Peter (2020), “Network-based hiring: Local benefits; global costs,” Unpublished manuscript.

Jakiela, P, and O Ozier (2016), “Does Africa need a rotten kin theorem? Experimental evidence from village economies,” The Review of Economic Studies, 83(1): 231–268.

Jayachandran, S (2021), “Microentrepreneurship in developing countries,” Handbook of Labor, Human Resources and Population Economics: 1–31.

Macchi, E, and J Stalder (2023), “Work over just cash: Informal redistribution,” Unpublished manuscript.

Riley, E. (2024). Resisting social pressure in the household using mobile money: Experimental evidence on microenterprise investment in Uganda. American Economic Review, 114(5), 1415-1447.

Squires, M (2024), “Kinship taxation as an impediment to growth: Experimental evidence from Kenyan microenterprises,” The Economic Journal, 134(662): 2558–2579.

Swanson, N (2024), “All in the family: Kinship pressure and firm-worker matching,” Unpublished manuscript.