Digitalisation reforms have become a popular policy tool in developing countries. Evidence from Pakistan, however, suggests that digitising land records can have unintended consequences on bureaucratic behaviour and, in turn, tax collection.

In the last few decades, the digitisation of public services has become ubiquitous. Building on the promises of e-governance, governments across the world have invested in computerising governmental records and making public services available to citizens online. Digitisation has touched almost every area of government: from improving education, to delivering better healthcare, collecting more taxes, strengthening property rights, and identifying recipients of welfare programmes.

One reason these reforms have been so popular is that digitisation can improve both the information that the state has about its citizens and the control it exerts over its functionaries. For instance, requiring firms to submit financial information electronically allows the state to know which firms owe taxes (Okunogbe and Pouliquen 2022). Similarly, using digital over physical payments ensures that government transfers reach the intended recipient, without being intercepted by corrupt intermediaries (Muralidharan et al. 2016, Blumenstock et al. 2023).

However, one aspect of this digital transformation is often under studied. Digitising services means that citizens interact less with the state, as public-facing officials are being increasingly replaced by online portals. The role of these officials, in turn, often changes drastically; the state may decide to change the tasks they carry out, move them to different parts of bureaucracies, or restructure the organisation. With fewer interactions, bureaucrats are also less likely to receive bribes, which might lead them to extract rents from other sources.

To understand the impact of these bureaucratic transformations, we analysed the effect of a digitisation reform in Punjab, Pakistan, on a key function of the state: collecting taxes (Aman-Rana and Minaudier 2025).

The digitisation of land records in Pakistan

In 2007, the local authorities in Punjab announced that they would digitise land records across the province, with the support of a US$45 million loan from the World Bank. The digitisation of land records has been a very popular reform across the world, with The World Bank Doing Business report recording 52 countries in which these reforms have taken place in the past ten years. In a typical version of the reform, the boundaries of individual properties are recorded and a registry of owners for each plot of land is created in a digital dataset. Any change of owner, due to sale or bequest, is recorded in this dataset. These digital records considerably reduce the risk of human error or deliberate tampering with the records. In turn, this reduces disputes between landowners and strengthens property rights. Without the fear of expropriation, landowners become more confident to invest in their land, increasing agricultural productivity and income.

The positive effects of land record digitisation have materialised in Punjab. Previous research shows that the reform led to higher farm productivity and income (Beg 2022). However, the reform also substantially reshaped the bureaucracy. Before the reform, bureaucrats in charge of tax collection were also those managing land records. After the reform, the management of computerised land records no longer needed to be decentralised and was transferred to a new team of bureaucrats. The public-facing officials who used to manage land records were now only in charge of assessing and collecting tax.

The unintended consequences of the digitisation reform

We find that this reorganisation had dramatic consequences for the state’s capacity to carry out its mission.

Reduced influence: First, the bureaucrats we surveyed reported that the digitisation reform led to a drop in their influence over the population. Before the reform, these bureaucrats’ control over the land records made them respected (and sometimes feared) members of the community. The land titles delivered by bureaucrats are essential for the population to obtain basic services such as electricity, gas, water, mortgages, or other official documents, and for selling or renting their land. Bureaucrats would also regularly arbitrate land disputes and determine ownership of disputed land parcels. This control gave bureaucrats leverage over landowners which they used for two purposes: obtaining bribes and encouraging farmers to pay their taxes.

Reduced tax collection: The most dramatic impact of the reform was a reduction in tax collection. Districts that were digitised collected 51% less taxes after the reform, relative to districts that were not digitised. Despite the additional time bureaucrats could now dedicate to tax collection, bureaucrats collected a lower amount of tax. The total amount of tax lost due to the reform represents up to 10% of the cost of the reform, which could have funded cash transfers for an additional 15,428 families as part of the government’s main social welfare programme (the Benazir Income Support Programme). This yearly tax loss represents 18% of the cost of running the digitised land record centres. We confirm that the decrease in tax was not driven by a decline in the tax base. The digitisation reform could, in principle, have reduced cultivated areas or agricultural income, on which the tax calculations are based. However, we found that the reform had no significant effect on cultivation or farm income. Instead, we found evidence that the drop in tax came from a change in the behaviour of bureaucrats.

Reduced assessment: The bureaucrats we studied completed two tasks to support tax collection. The first was to assess the tax due by farmers via farm inspections. We find that bureaucrats reported that farmers cultivated 10% lower areas in digitised districts after the reform, relative to non-digitised districts. Since we find that the actual tax base did not decrease, the digitisation reform seems to have led bureaucrats to underreport the tax base. Farm inspections are carried out by individual bureaucrats, opening the door to collusion with taxpayers. The bureaucrats we surveyed reported that they frequently faced pressure from taxpayers to lower their tax bills. One possible explanation is therefore that digitisation led to an increase in collusion. This explanation would be consistent with a bribe displacement story: bureaucrats who no longer earn bribes from providing land services transfer their bribe collection to tax assessment. It is also consistent with the loss of influence that bureaucrats experienced: with less need for the bureaucrat’s help with land services, taxpayers are less afraid to underreport their income.

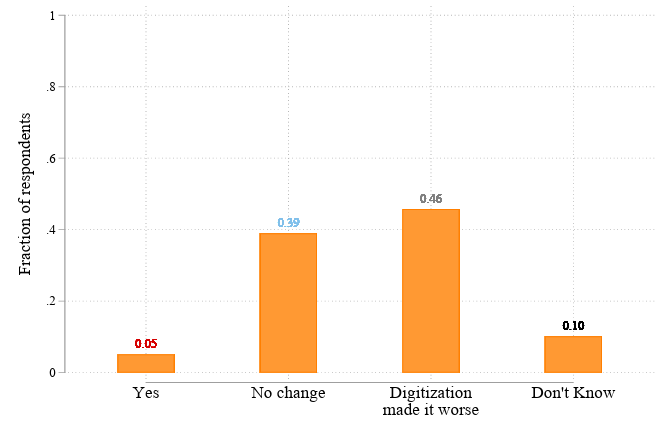

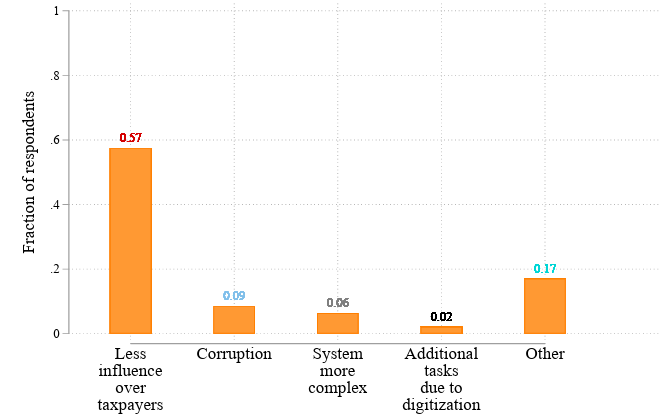

Reduced bureaucratic performance: The bureaucrats’ second task was to collect the taxes that are due. Few farmers pay their taxes up front, making bureaucrat involvement necessary to collect payments. We find that the bureaucrats’ tax collection as a percentage of the assessed tax due fell by 58%. This is despite the tax due decreasing, which should have made it easier to collect. This effect is also consistent with the loss of influence that we document. Before the reform, the promise to quickly process land titles or resolve land disputes in a farmer’s favour gave the bureaucrats leverage, which they could use to encourage farmers to pay the taxes they owed. Without this leverage, taxpayers became more likely to evade taxes. This was the explanation bureaucrats themselves provided (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Bureaucrats’ views on the effect of digitisation on tax collection

(a) “Has digitisation improved tax collection?”

(b) “If no, please explain how”

Policy lessons for digitalising bureaucracies

Our analysis of the land record reform in Punjab highlights that digitisation can have unintended consequences on the functioning of the state, even potentially on areas that were not directly targeted by the reform. These findings suggest that governments should be cautious when implementing this kind of reform and consider the wide-ranging implications they could have.

First, governments should carefully consider the impact of digitisation on the organisation of the bureaucracy. Will the digitisation reform replace tasks that bureaucrats were accustomed to with less familiar tasks? Will the restructuring of bureaucracy remove complementarities between tasks? Will it change the relationship between government officials and the population? Will it remove informal arrangements that helped the state enforce the law?

Second, if a digitisation reform is likely to impact the broader structure of the bureaucracy, the government should consider combining the reform with organisational changes. For instance, new incentive schemes could redirect the effort of bureaucrats towards the right tasks. In recent years, the government of Punjab has reviewed the career paths of the bureaucrats affected by the reform and tried to incorporate the bureaucrats into the new digitalised system. Alternatively, proposing new community-based tasks for the bureaucrats could rebuild the connection with the population that bureaucrats lost due to digitisation.

Finally, the government should consider ‘big push’ reforms, whenever feasible. Rather than digitising one part of the bureaucracy at a time, the government should consider the possibility of introducing technology in multiple related areas at the same time. These reforms would ensure that administrative tasks that have not yet been modernised do not suffer negative spillovers from those that already have.

References

Aman-Rana, S, and C Minaudier (2024). "Spillovers in State Capacity Building: Evidence from the Digitization of Land Records in Pakistan," Unpublished manuscript.

Beg, S (2022), “Digitization and development: Property rights security, and land and labor markets,” Journal of the European Economic Association, 20(1): 395–429.

Blumenstock, J E, M Callen, A Faikina, S Fiorin, and T Ghani (2023), “Strengthening fragile states: Evidence from mobile salary payments in Afghanistan,” Unpublished manuscript.

Muralidharan, K, P Niehaus, and S Sukhtankar (2016), “Building state capacity: Evidence from biometric smartcards in India,” American Economic Review, 106(10): 2895–2929.

Okunogbe, O, and V Pouliquen (2022), “Technology, taxation, and corruption: Evidence from the introduction of electronic tax filing,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 14(1): 341–372.