A surge in beef exports to China triggered widespread growth in Uruguay’s service sector.

Editor’s note: For a broader synthesis of themes covered in this article, check out Issue 2 of our VoxDevLit on International Trade.

Over the past two decades, China's rapid industrialisation and rising middle class have transformed global trade patterns. While much attention has been paid to China's rise as a manufacturing export powerhouse (Autor et al. 2013, Pierce and Schott 2016, Caliendo et al. 2019), its surging demand for commodities has had equally profound effects—especially on exporting countries in the Global South. Many developing economies have witnessed a sharp increase in exports to China, concentrated in a few key commodities. For instance, countries such as Brazil, Peru, and Argentina have expanded exports of soy, copper, and beef (Costa et al. 2016), while African nations such as the Democratic Republic of Congo and Mozambique have seen a boom in cobalt and timber exports. These dynamics are poised to intensify further as the US-China trade war escalates. As China shifts agri-food imports away from the US, new opportunities arise for alternative exporters in the developing world.

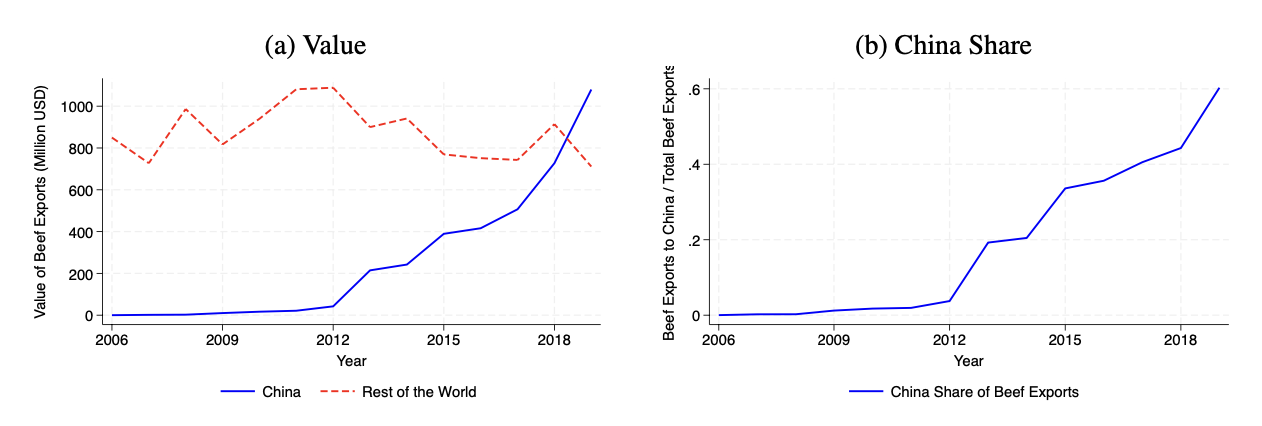

Uruguay, a South American country with a strong beef export capacity, provides a compelling case study. Between 2006 and 2019, Uruguay’s beef exports to China skyrocketed from USD$3.56 million to over USD$1.13 billion, making China the destination for approximately 60% of the country’s total beef exports. By 2019, beef exports to China alone accounted for 1.7% of Uruguay’s GDP, while exports to the rest of the world remained largely flat.

Figure 1: Uruguayan beef exports to China and the rest of the world

Beyond the farm: Tracing the ripple effects of export booms on the rest of the economy

While the direct benefits to Uruguay’s beef exporters are straightforward, our research (Amodio et al. 2025) set out to understand a more complex question: How do export booms affect the rest of the economy? Do the benefits of trade stop at the farm gate and the slaughterhouse, or do they ripple out to upstream and downstream suppliers across sectors? If so, which firms and sectors benefit the most? And do these linkages simply pass through the shock, or do they change in response, reshaping how firms interact and how the economy is organised?

To explore this, we constructed a unique dataset by integrating customs records with confidential administrative tax data, firm-to-firm transaction records, employer-employee matched data, and firm balance sheets. This comprehensive data infrastructure allowed us to trace domestic production linkages and examine how a shock to beef exports to China propagated through Uruguay’s production network.

Our analysis begins by focusing on first-order suppliers—that is, firms that sold goods or services to beef exporters at baseline. Within this group, we exploit variation within sectors in their degree of exposure to beef exporters based on the share of their sales going to these exporters. We combine this baseline variation in exposure with year-by-year changes in beef exporters’ actual trade with China. This gives us a Bartik-style instrument that captures how much each supplier was indirectly affected by the export surge.

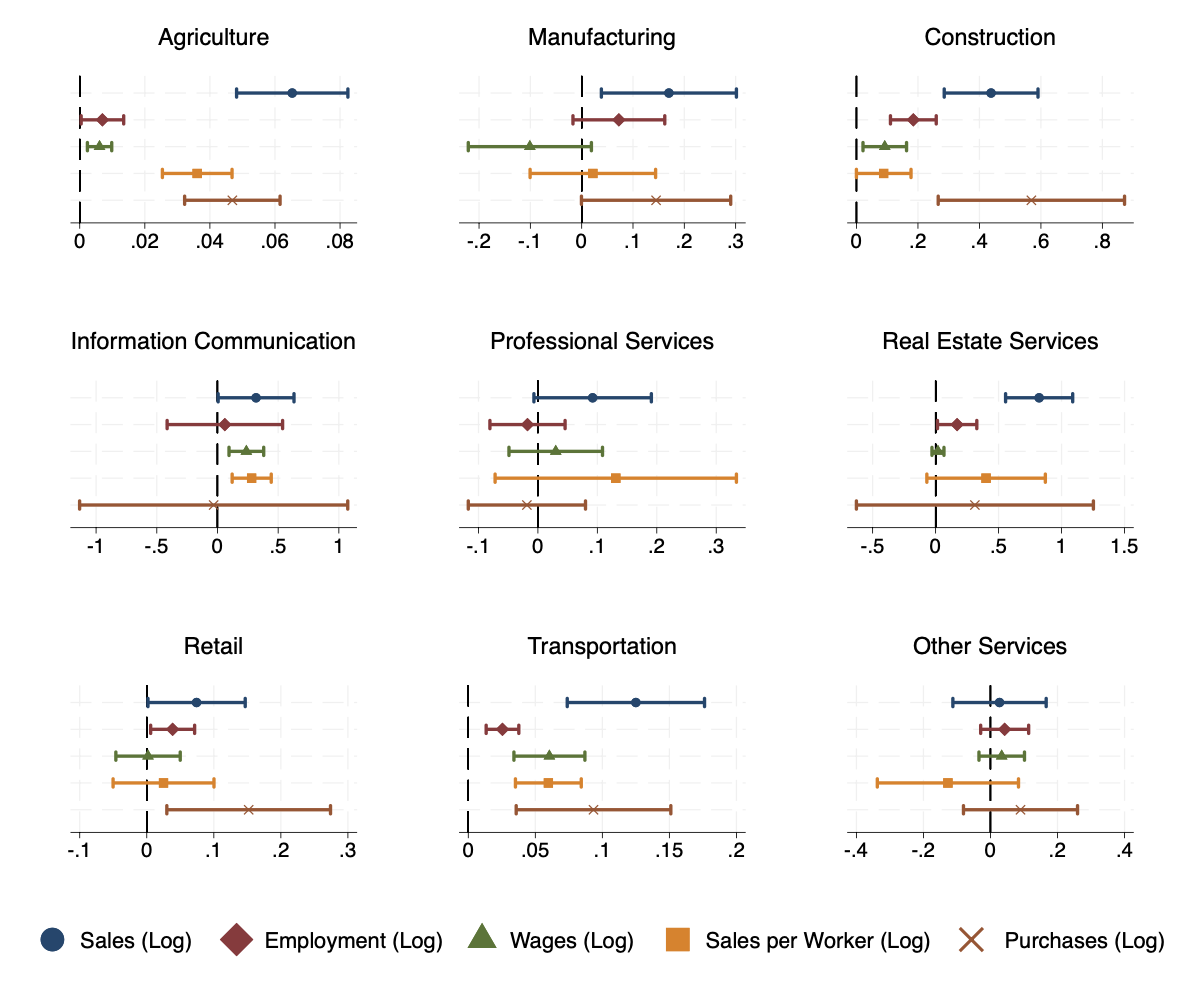

Using this approach, we find that a one standard deviation increase in indirect exposure to the China beef boom led to an 8% increase in total sales among suppliers. For service sector firms, the effect rises to 14%, with similarly strong gains in employment (+3%), wages (+3%), and sales per worker (+7%). These effects are especially pronounced among smaller firms, and among those in sectors such as retail, transportation, real estate, professional services, and ICT. These findings suggest that trade booms can activate wide swaths of the domestic economy—not only through agricultural production, but also through the services that exporters rely on to grow.

Figure 2: The impact of the China beef export shock on suppliers’ outcomes by sector

These results demonstrate that the benefits of trade are not confined to exporters themselves. Rather, they ripple through the domestic economy, activating a wide network of upstream firms that supply exporters with the goods and services they need to operate and expand. Moreover, we find evidence of second-order effects: firms that supply the suppliers of beef exporters also experienced growth, particularly those in service industries such as IT, transportation, and professional services. In the case of Uruguay’s beef boom, this ripple effect was not only sizable—it was transformative, especially for the country's service sector.

Quantifying the spillover effects of export booms: A Network Perspective

While our reduced-form analysis shows that firms connected to beef exporters grew faster, it does not tell us how large the overall impact was on the Uruguayan economy. To do this, we turn to a network-based accounting framework that lets us go beyond individual firm outcomes and quantify the total aggregate effect of the beef export boom. This approach allows us to overcome a key limitation of our earlier reduced-form analysis: the so-called ‘missing intercept’ problem, which prevents us from estimating levels and aggregate changes directly.

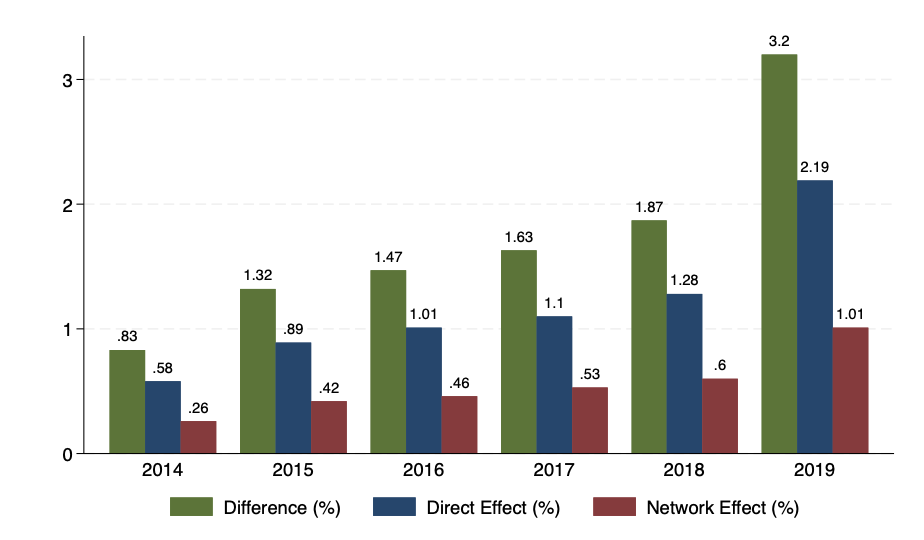

This framework also allows us to separate the direct effects of exports (i.e. the value of beef sales to China) from the indirect effects that ripple through the domestic economy via supplier linkages. Using this method, we estimate that beef exports to China increased Uruguay’s aggregate sales by 1.79% between 2014 and 2019, with about one-third of this increase coming from indirect effects through the production network.

Finally, we use the model to study how the structure of the economy itself evolved in response to the beef export shock. Firms didn’t just grow—they restructured their supplier relationships, forming new links and expanding their networks. This endogenous reshaping of the production network amplified the shock, particularly for the service sector, which accounted for 22% of the network-driven gains. These results suggest that the domestic economy adapted dynamically to the new export opportunity, enabling services to play a key role in spreading the benefits.

Figure 3: Actual versus estimated counterfactual sales in the absence of China beef exports, decomposed by direct and network effects

Policy implications: Leveraging commodity booms for economic growth

Uruguay’s experience offers important lessons for other commodity-exporting countries—particularly at a time when global trade patterns are being reshaped. The US-China trade war and China’s efforts to diversify away from US agri-food imports create opportunities for alternative suppliers. Countries like Uruguay stand to benefit from these shifts, but realising the full potential of such trade opportunities requires deliberate policy efforts to ensure that gains are realised.

Our research offers several insights for policymakers:

- Recognise the potential of services: Commodity booms can stimulate growth beyond the primary sector. By identifying and supporting service sectors that are closely linked to export industries, countries can amplify the benefits of trade surges.

- Strengthen production networks: Facilitating connections between exporters and domestic suppliers can enhance the transmission of positive shocks throughout the economy. Policies that promote information sharing, infrastructure development, and access to finance can be instrumental.

- Monitor and support structural changes: As sectors adapt to new opportunities, targeted support can help firms navigate transitions, ensuring that growth is inclusive of the broader economy, beyond the directly affected sectors.

Conclusion: Rethinking pathways for development

Uruguay’s experience challenges conventional narratives about Dutch Disease while providing empirical support for a growing body of work that highlights the role of labour-absorbing, tradable services as a viable pathway for structural change and development (Rodrik and Sandhu 2024). Our findings show that, under the right conditions, commodity export booms can generate wide-ranging benefits, catalysing growth not only in the export sector but also across a dense network of domestic service providers.

References

Amodio, F, G Chiovelli, and S Frache (2025), “Beefing up the service sector: Commodity exports to China and production network spillovers,” Unpublished manuscript.

Autor, D, D Dorn, and G Hanson (2013), “The China Syndrome: Local labor market effects of import competition in the United States,” American Economic Review, 103(6): 2121–68.

Caliendo, L, M Dvorkin, and F Parro (2019), “Trade and labor market dynamics: General equilibrium analysis of the China trade shock,” Econometrica, 87(3): 741–835.

Costa, F, J Garred, and J P Pessoa (2016), “Winners and losers from a commodities-for-manufactures trade boom,” Journal of International Economics, 102: 50–69.

Pierce, J R, and P K Schott (2016), “The surprisingly swift decline of U.S. manufacturing employment,” American Economic Review, 106(7): 1632–62.

Rodrik, D, and R Sandhu (2024), “Servicing development: Productive upgrading of labor-absorbing services in developing economies,” Unpublished manuscript.