The sudden rollback of Mexico’s landmark conditional cash transfer programme—Prospera, formerly Progresa—affected boys’ educational outcomes disproportionately, offering lessons for policy retrenchment worldwide.

For over two decades, economists and policymakers in over 60 countries have supported the use of conditional cash transfers (CCT) programmes to fight poverty—both current and future. CCT programmes have the dual objectives of reducing current poverty—through cash—and future poverty—through investments in human capital for the next generation incentivised via the conditionality of transfers. Research has extensively documented the success of these programmes in keeping youth in school and out of the labour force, along with a host of other health and economic benefits (Schady et al. 2009). The pioneering randomised controlled trial and evaluation of Mexico's CCT programme Progresa—later renamed Oportunidades and then Prospera—served as an archetype for the impact evaluation movement.

However, after successfully operating for more than twenty years, Prospera suddenly and abruptly ended. We study the schooling and labour impacts of rolling back Prospera, which on the eve of rollback provided benefits to approximately one-fourth of Mexican households. We find that its discontinuation led to an immediate drop in high school enrolment, particularly for young men, even despite the implementation of a substitute programme.

Our findings shed light on the important yet understudied topic of whether programme gains persist after transfers end. Prior research has focused on whether positive effects in short-term pilot studies are maintained post-pilot (Haushofer and Shapiro 2018, Baird et al. 2019, Blattman et al. 2020). Our research extends this literature to the context of a pioneering and longstanding nationwide programme in Latin America, providing evidence on the benefits of continued investment in CCT programmes by governments and multilateral organisations.

A short history of Progresa: Rollout, rollback, and replacement

Originally implemented in 1997, Progresa lasted through three presidential transitions without major changes. At the time of its sudden rollback, it supported seven million low-income households through direct monetary transfers conditioned on school enrolment and attendance as well as preventive health clinic visits, increasing beneficiaries’ average incomes by about 30%. A well-known randomised controlled trial in 1997 found positive effects on a host of variables, including school enrolment, child health, household consumption and women’s status, among others (Parker and Todd 2017). By 2013, 137 million individuals across Latin America were receiving CCTs (Ibarrarán et al. 2017). The evidence on the effectiveness of these programmes has been overwhelmingly positive, both in the short- and long-term (Parker and Vogl 2023).

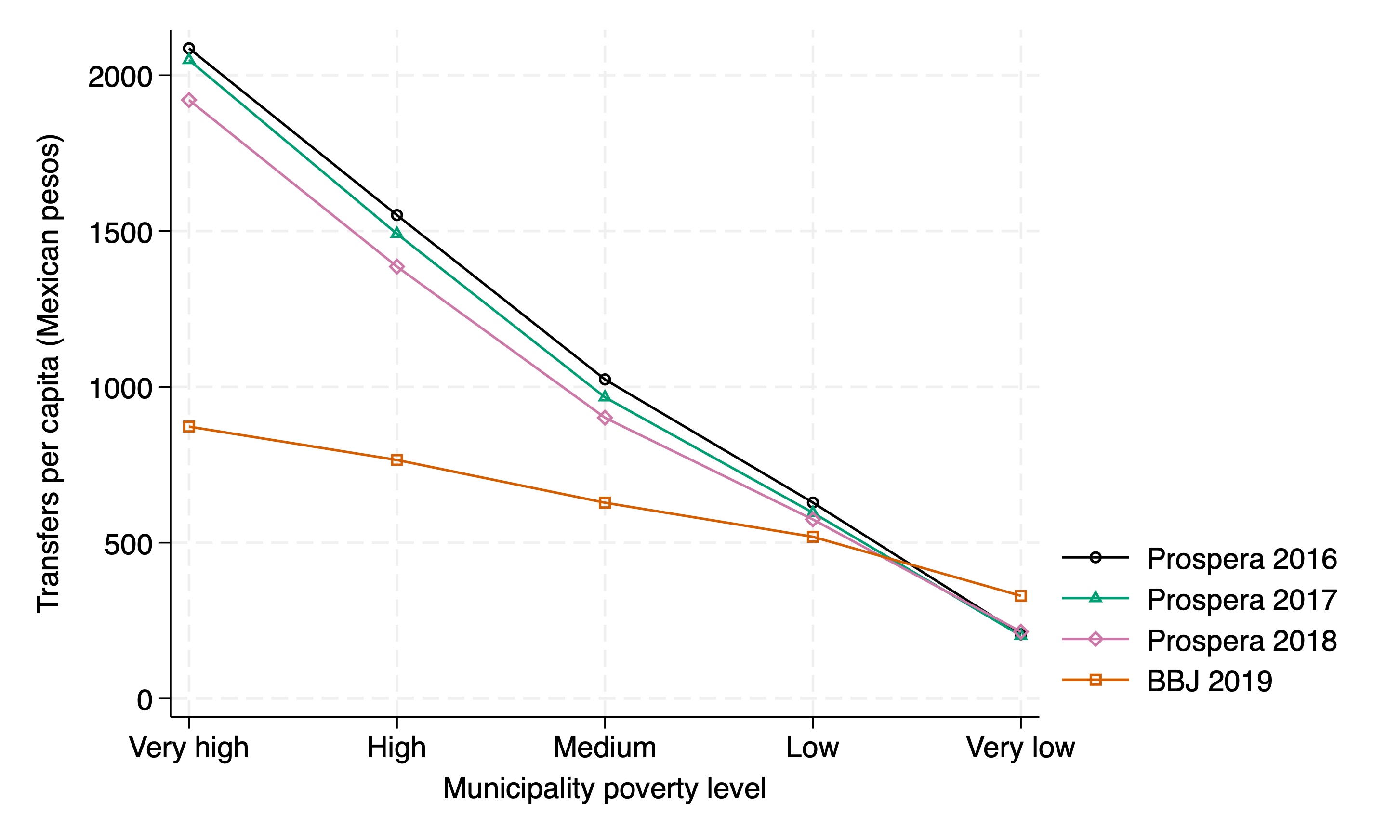

In spite of this large existing body of evidence, shortly after Andrés Manuel López Obrador assumed the Mexican presidency, his government unexpectedly announced that Prospera would transition to a new education grant programme called Becas Benito Juárez (BBJ). On paper, both BBJ and Prospera provided transfers conditional on school enrolment, although BBJ reduced the use of means-testing, loosened conditionality, and stopped monitoring attendance. While total overall spending remained similar, BBJ severely reduced targeting of the poor, slashing support to beneficiary households in the poorest parts of Mexico. Figure 1 illustrates the change in spending by municipal level poverty.

Figure 1: Transfers per capita by municipality poverty level and year

Notes: Data on transfers are from the administrative database for each programme. Data on population and marginalisation are for 2015, from the National Population Council of Mexico.

Studying the impact of Progresa rollback on education and employment outcomes

To analyse the effects of Prospera’s rollback, we leverage geographic variation in programme penetration merged to school and labour data from Mexico’s National Survey of Occupation and Employment (Marquez-Padilla et al. 2025). We compare schooling and labour outcomes before and after rollback between localities with higher and lower shares of beneficiaries. Rollback started in March 2019, so we concentrate on the impact on school enrolment in the fall of 2019, about six months after rollback and prior to the onset of COVID-19 in March 2020. In our econometric specification, we compare changes in outcomes between localities within the same state, allow for anticipatory effects, and estimate the effects of rollback net of the new BBJ transfers.

Following Progresa rollback, enrolment dropped immediately, particularly among high-school-aged boys

We study rollback’s effects on enrolment for three age groups, roughly corresponding to primary, middle, and high school enrolment ages. We find that rollback led to an immediate decline in school enrolment, concentrated in teenage boys. Within six months of rollback, school enrolment in this demographic declined by 12 percentage points—or 17% of the mean of around 70% pre-rollback. This decline is larger for boys from the most disadvantaged households, where enrolment declined by 18 percentage points, or 29% of average enrolment.

A substitute programme failed to stem the damage

Our results are striking, especially as they account for the implementation of the BBJ programme, which was launched in 2019 prior to Prospera’s rollback. However, we demonstrate that the transition to BBJ drastically reduced benefit payments in Prospera communities, and find little evidence that the new programme protected enrolment. We determine that, prior to COVID-19, BBJ moved resources away from the poor, rural communities at the centre of Prospera, with little apparent benefit.

Why do girls appear more protected from the sudden shock of Prospera’s rollback?

Surprisingly, we do not observe large reductions in high school enrolment post-rollback among girls. One possible explanation is that Prospera’s emphasis on gender and preferential treatment of girls shielded them from rollback by improving their families’ attitudes towards their education. Another explanation is that teenage girls have fewer work opportunities than boys, lowering their opportunity costs of staying in school.

From the schoolyard to the labour force

We find that work opportunities may explain the gender gap in enrolment. Our estimates show significant impacts on boys’ labour supply, but not girls’ (Bai and Wang 2020). They suggest that more than 1 in 2 rollout-attributable dropouts joined the labour force upon leaving school. We present evidence of large lifetime economic returns to completing high school for boys on the margin of dropping out. However, earnings trajectories suggest these returns may not accrue for many years, so a high school aged boy considering dropout might not see much near-term benefit to staying in school, especially if liquidity constrained or present-biased.

Lessons for a world grappling with development funding cuts

The Mexican government unexpectedly rolled back its pioneering conditional cash transfer programme after more than two decades of successful operation. This episode is part of a broader wave of social programme retrenchment under populist leadership across several countries, on the right and left. Over its long tenure, Mexico’s CCT—most recently known as Prospera—had demonstrated clear, accumulating benefits for educational attainment, and nonetheless it disappeared almost overnight.

Social programme retrenchment often occurs without close regard for evidence, which makes it all the more critical to rigorously evaluate such episodes. Our findings provide timely empirical evidence to inform the design and sustainability of CCTs in Mexico and globally. Two decades after their inception, conditional cash transfer programmes are backed by a large body of evidence on short- and medium-run effects, and growing research points to positive longer-run outcomes. Our findings underscore that sudden rollbacks can rapidly undo this progress and serve as a cautionary tale against replacing proven programmes with untested alternatives.

References

Bai, J and Y Wang (2020), “Returns to work, child labour and schooling: The income vs. price effects”, Journal of Development Economics, 145.

Baird, S, C McIntosh, and B Özler (2019), “When the money runs out: Do cash transfers have sustained effects on human capital accumulation?”, Journal of Development Economics, 140: 169–185.

Blattman, C, N Fiala, and S Martinez (2020), “The long-term impacts of grants on poverty: Nine-year evidence from Uganda’s Youth Opportunities Program”, American Economic Review: Insights, 2(3): 287–304.

Haushofer, J and J Shapiro (2018), “The long-term impact of unconditional cash transfers: Experimental evidence from Kenya”, Unpublished manuscript.

Ibarrarán, P, C Medellín, J Regalia, and M Stampini (2017), "How conditional cash transfers work", Inter-American Development Bank.

Marquez-Padilla, F, S W Parker, and T S Vogl (2025), “Rolling back Progresa: School and work after the end of a landmark anti-poverty program”, Unpublished manuscript.

Parker, S W and P E Todd (2017), “Conditional cash transfers: The case of Progresa/Oportunidades”, Journal of Economic Literature, 55(3): 866–915.

Parker, S W and T Vogl (2023), “Do conditional cash transfers improve economic outcomes in the next generation? Evidence from Mexico”, The Economic Journal, 133(655): 2775–2806.

Schady, N, A Fiszbein, F H G Ferreira, N Keleher, M Grosh, P Olinto, and E Skoufias (2009), "Conditional cash transfers: Reducing present and future poverty", World Bank.