A bundled farm programme in western Kenya boosted yields and profits for smallholders by jointly tackling credit, information, and risk constraints.

Editor’s note: For a broader synthesis of themes covered in this article, check out Issue 2 of our VoxDevLit on Agricultural Technology in Africa.

Smallholder productivity in low-income countries remains stagnant—and may even be declining (Wollburg et al. 2024). In sub-Saharan Africa, the challenge is particularly acute (Suri et al. 2024). Despite large public investments, productivity in sub-Saharan Africa lags behind other developing regions (World Bank 2008, Block 2014).

Policymakers continue to debate whether scarce public resources should target smallholder farmers or shift support to medium- and large-scale commercial operations (Jayne et al. 2016). The stakes are high, as agriculture drives poverty reduction and fuels economic growth (Bravo-Ortega and Lederman 2005, Gollin et al. 2021, Ligon and Sadoulet 2011, Ravallion and Chen 2007). GDP growth in the agriculture sector lifts incomes from the poorest segments of the population at three times the rate of growth in other sectors (de Janvry and Sadoulet 2010).

Most of sub-Saharan Africa’s arable land is owned by smallholders, who produce the majority of its food. Leaving them out of public investments would sideline millions whose livelihoods depend on farming, deepening rural poverty. Still, agricultural development programmes have repeatedly failed to meaningfully shift outcomes for smallholders.

Many interventions addressing an isolated potential constraint on yields—such as a lack of access to modern inputs or poor information about effective farming methods—fail to significantly improve productivity (Udry et al. 2019, Cole and Fernando 2021). This pattern raises a crucial question: do programmes fail because they attack the wrong problem, or because they are tackling each constraint in isolation?

A bundled agricultural programme boosted yields in Kenya

Our recent research on One Acre Fund’s large-scale programme serving smallholder maize farmers adds new insights into this question (Deutschmann et al. 2025). The One Acre Fund programme stands out because it bundles key services into a single package: it provides credit for high-quality seeds and fertiliser, delivers them close to farmers’ homes, offers insurance to reduce risk, and trains farmers in improved agricultural practices. Though these concepts are not new, in practice they are rarely combined into a comprehensive package and delivered to farmers at scale.

We evaluated the effectiveness of the programme using a large-scale randomised controlled trial in western Kenya. We randomly assigned programme access at the farmer group level and tracked effects using detailed farm surveys and physical measurements of production and farming practices. This allowed us to estimate the causal impact of the One Acre Fund bundle on farmer behaviour, yields, and profits.

The programme delivered clear benefits. Maize yields rose by 26% and output by 24%. Despite spending more on inputs, participating farmers earned more, as well—profits increased by 18%. These results were both statistically significant and economically meaningful—they reflect real changes in farmers’ productivity and welfare.

Bundling agricultural programmes tackle multiple constraints

There is a growing consensus that no single constraint explains the low productivity in African agriculture. Therefore, bundled programmes may outperform programmes that address one constraint at a time. A farmer who gets credit but lacks training on best practices may use inputs inefficiently. Training alone is not useful if the farmer cannot afford to buy the seeds and fertiliser they have learned about. And risk exposure may still hold farmers back from making extra investments, even with access to credit and training. Bundled programmes address these problems together, and each component may reinforce the others.

Our findings support this idea. Treated farmers adopted better agronomic practices, like using correct spacing between plants and applying fertiliser at the right time. Though proper fertiliser timing may seem like a basic productivity-enhancing step, we know from previous research that even highly experienced producers can fail to notice crucial features of the production process (Hanna et al. 2014) or less-salient profitability margins (Beaman et al. 2013, Duflo et al. 2008).

We also saw large increases in input use. Enrolled farmers spent 91% more on fertilier, 26% more on seeds, and nearly 20% more on labour, once they had access to credit. They also allocated 13% more land to maize. These shifts suggest that the farmers faced binding credit constraints that were unlocked by programme participation.

Programme effects extended beyond the farm. Access to agricultural credit freed up liquidity at the same time of the year that school fees were due, and participating farmers increased their school fee spending by 50-70% relative to the control group. These patterns underscore the importance of liquidity constraints in this context.

The programme delivered strong returns, even after accounting for costs

Policymakers are right to worry about the cost-effectiveness of bundled programmes. Bundled programmes require more coordination, and each added component raises implementation costs. But our cost-benefit analysis, which calculates the net social benefit of the programme, taking donor contributions into account, shows that the benefits outweigh those costs.

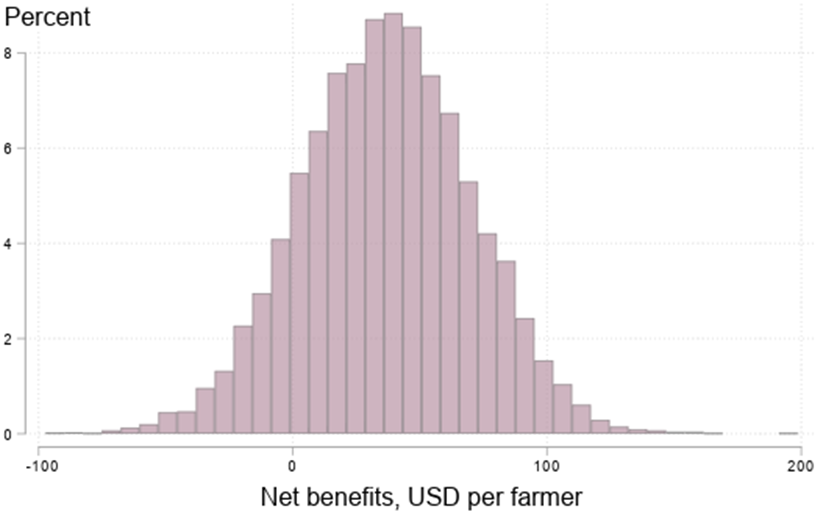

Figure 1 shows simulated distributions of net social benefits from the One Acre Fund programme, combining variation in donor subsidy costs across years with block-bootstrapped profit impacts. Even after accounting for uncertainty via simulations, and adjusting for donor contributions, the programme generated an average net social benefit of about US$37 per farmer. In the conservative scenario shown in Figure 1, over 86% of the 10,000 simulations show a positive societal net benefit.

Figure 1: Distribution of net benefits

These findings align with evidence on multifaceted anti-poverty ‘graduation’ programmes (Banerjee et al. 2015, Bandiera et al. 2017, Balboni et al. 2022, Abed 2025), which target multiple constraints to help households ‘graduate’ from poverty and often outperform programmes that target single constraints.

That said, bundled programmes are not easy to run. Targeting, delivery, and cost management matter. Implementers need strong systems capable of handling multiple components simultaneously. One Acre Fund appears to succeed in part because the NGO has invested in managing this complexity at scale.

Implications for agricultural policy

The agricultural productivity gap in sub-Saharan Africa is real—but it is not immutable. Our findings show that smallholder farmers can produce and earn more when they receive the right mix of support. Bundled programmes offer one way to deliver that support. They address multiple barriers together and produce large gains. But success depends on careful design and effective delivery. Policymakers should invest in understanding what makes bundled programmes work and explore how to scale them up without sacrificing quality.

Bundling will not solve every challenge. But where multiple constraints hold farmers back, it provides a potential path for effective agricultural policy. Designing programmes to precisely identify and target the specific constraints that each farmer faces can also be costly. In settings with high logistics and transportation costs and relatively low marginal costs, bundling may be efficient even if not every farmer needs every component. With the right structure and support, bundled programmes can play a key role in transforming agriculture across sub-Saharan Africa.

References

Abed, S (2025), “Targeting the ultra-poor through the Graduation approach: Insights from BRAC”, VoxDev.

Balboni, C, O Bandiera, R Burgess, M Ghatak, and A Heil (2022), “Why do people stay poor?”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 137: 785–844.

Bandiera, O, R Burgess, N Das, S Gulesci, I Rasul, and M Sulaiman (2017), “Labor markets and poverty in village economies”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132: 811–870.

Banerjee, A, E Duflo, N Goldberg, D Karlan, R Osei, W Pariente, J Shapiro, B Thuysbaert, and C Udry (2015), “A multifaceted program causes lasting progress for the very poor: Evidence from six countries”, Science, 348: 1260799.

Beaman, L, D Karlan, B Thuysbaert, and C Udry (2013), “Profitability of fertilizer: Experimental evidence from female rice farmers in Mali”, American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, 103: 381–386.

Block, S (2014), “The decline and rise of agricultural productivity in Sub-Saharan Africa since 1961”, in African Successes, University of Chicago Press for the National Bureau of Economic Research: 13–67.

Bravo-Ortega, C and D Lederman (2005), “Agriculture and national welfare around the world: Causality and international heterogeneity since 1960”, World Bank.

Cole, S A and A N Fernando (2021), “‘Mobile’izing agricultural advice: Technology adoption, diffusion and sustainability”, The Economic Journal, 131: 192–219.

de Janvry, A and E Sadoulet (2010), “Agricultural growth and poverty reduction”, World Bank Research Observer, 25: 1–20.

Deutschmann, J, M Duru, K Siegal, and E Tjernström (2025), “Relaxing multiple agricultural productivity constraints at scale”, Journal of Development Economics, 174.

Duflo, E, M Kremer, and J Robinson (2008), “How high are rates of return to fertilizer? Evidence from field experiments in Kenya”, American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, 98: 482–488.

Gollin, D, C W Hansen, and A M Wingender (2021), “Two blades of grass: The impact of the Green Revolution”, Journal of Political Economy, 129: 2344–2384.

Hanna, R, S Mullainathan, and J Schwartzstein (2014), “Learning through noticing: Theory and evidence from a field experiment”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129: 1311–1353.

Jayne, T, J Chamberlin, L Traub, N Sitko, M Muyanga, F K Yeboah, W Anseeuw, A Chapoto, A Wineman, C Nkonde, and R Kachule (2016), “Africa’s changing farm size distribution patterns: The rise of medium-scale farms”, Agricultural Economics, 47: 197–214.

Ligon, E A and E Sadoulet (2011), “Estimating the effects of aggregate agricultural growth on the distribution of expenditures”, Unpublished manuscript.

Ravallion, M and S Chen (2007), “China’s (uneven) progress against poverty”, Journal of Development Economics, 82: 1–42.

Suri, T, C Udry, J C Aker, C B Barrett, L Falcao Bergquist, M Carter, L Casaburi, R Darko Osei, D Gollin, V Hoffmann, T Jayne, N Karachiwalla, H Kazianga, J Magruder, H Michelson, M Startz, and E Tjernström (2024), “Agricultural technology in Africa”, VoxDevLit, 5(2), March.

Udry, C, F di Battista, M Fosu, M Goldstein, A Gurbuz, D Karlan, and S Kolavalli (2019), “Information, market access and risk: Addressing constraints to agricultural transformation in Northern Ghana”, Unpublished manuscript.

Wollburg, P, T Bentze, Y Lu, C Udry, and D Gollin (2024), “Crop yields fail to rise in smallholder farming systems in sub-Saharan Africa”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(21).

World Bank (2008), World Development Report 2008: Agriculture for Development, World Bank.