New research sheds light on how illegal animal trade contributes to disease transmission, and shows how robust border inspections can effectively curb this impact.

Editor’s note: For a broader synthesis of themes covered in this article, check out Issue 2 of our VoxDevLit on International Trade.

Global trade in live animals has grown rapidly in recent decades, reflecting a variety of motives—from livestock production to exotic pets and traditional medicine. While legal trade channels normally follow testing and quarantine protocols designed to prevent the spread of infectious diseases, illicit trade in live animals escapes these regulations. Like other illicit markets such as narcotics or cultural artifacts, illicit trade in live animals is often driven by efforts to evade costs, bans, or regulatory scrutiny (Fisman and Wei 2004, Fisman and Wei 2009, Vézina 2015, Rotunno and Vézina 2017). However, when it comes to animals, circumventing official checks poses a heightened public good threat. Not only can infected animals cross borders undetected, but contact between different species along the way can further fuel the spread of disease-causing pathogens.

Such risks have drawn increasing attention since the early 2000s, especially after high-profile zoonotic events like Avian Flu, Ebola, MERS-COV, and more recently COVID-19. Indeed, at least 60% of infectious pathogens in humans originate in animals (Karesh et al. 2005). Epidemiology and veterinary science research has long cautioned that illicit animal trade flows can transmit diseases to local livestock, wildlife, and eventually humans (Beltran-Alcrudo et al. 2019). Yet, detailed economic analysis quantifying the damage caused by illicit live animal trade has been scarce. This article summarises our recent work (Beverelli and Ticku 2025), showing that countries experiencing high levels of missing imports in live animals—an established proxy for smuggling—are more likely to suffer higher transmission of infectious diseases in those same species.

The importance of understanding how illicit animal trade impacts public health

Research has highlighted how the benefits of globalisation can be accompanied by health risks linked to the heightened movement of people and goods (Oster 2012, Lin et al. 2022, Antràs et al. 2023). The spread of livestock diseases requires special policy attention. Major outbreaks can devastate rural livelihoods, especially in developing countries where livestock assets serve as a buffer against poverty (Lybbert et al. 2004, Santos and Barrett 2011). Outbreaks also threaten food security (Murphy and Allen 2003). While much research focuses on legal trade, the role of illicit channels has been comparatively overlooked. Linking the illicit trade dimension to the above-mentioned welfare effects sheds light on why better border controls and regulatory enforcement matter so much for animal, and eventually human, well-being.

Measuring illicit animal trade

A key challenge in studying illegal activity is that it evades official measurement. Building on approaches pioneered by trade economists (Fisman and Wei 2004, Javorcik and Narciso 2008, Rotunno and Vézina 2013), we measure ‘missing imports’ by comparing the value of all exports of live animal products declared by partner countries with what the importing country itself reports as imports. When partner countries’ reported exports substantially exceed the importing country’s recorded imports, net of normal reporting discrepancies,[1] we infer that under-reporting or smuggling is taking place.

We corroborate this proxy in two ways:

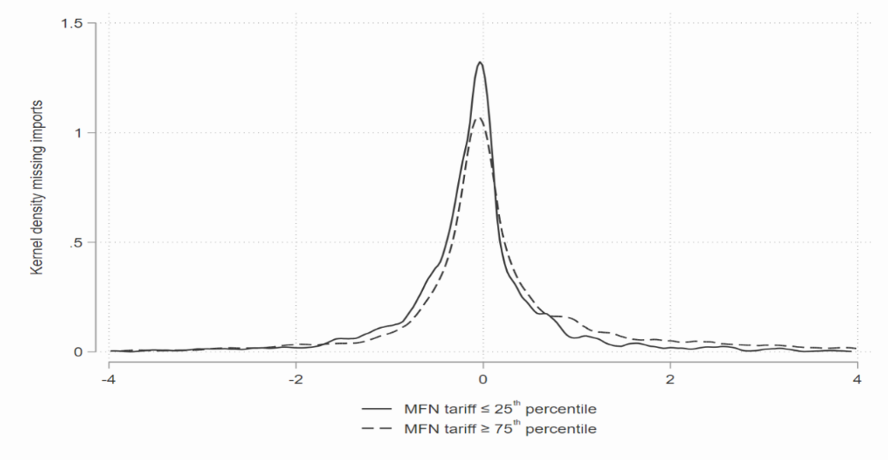

- Tariff evasion link: As shown in Figure 1, we find that discrepancies grow with higher import tariffs, consistent with earlier literature demonstrating that importers under-report consignment values for tax avoidance (Fisman and Wei 2004).

- Confiscations: Where customs seize a greater number of illegally imported live animal specimens, missing imports also tend to be higher. This is consistent with the interpretation that missing imports genuinely reflect smuggling rather than mere statistical noise.

Figure 1: Distribution of missing imports at different tariff rate thresholds

Illicit animal trade contributes to disease transmission

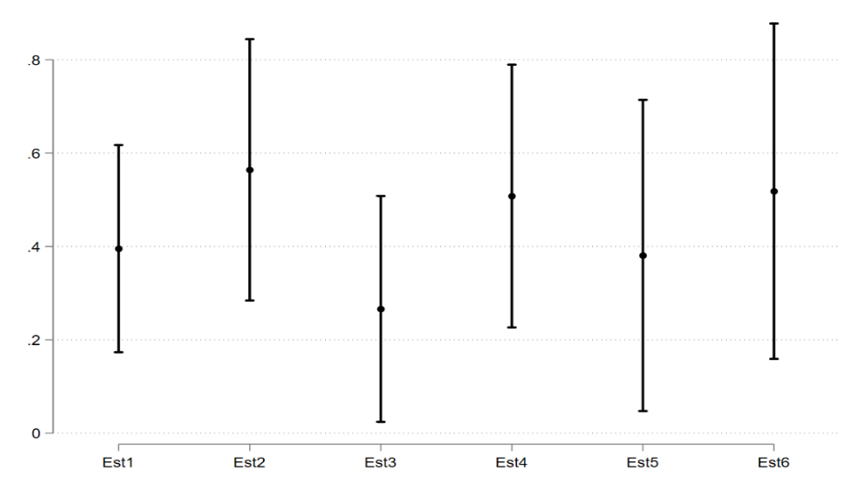

Using data on nearly one hundred thousand recorded outbreaks of infectious animal diseases from 2004 to 2019, we show that importing countries with larger missing imports in a given live animal category—cattle, swine, poultry, and so forth—record significantly more infected animals in that same category. Across different econometric models, we find that a 1% increase in missing imports of a particular live animal category is associated with a 0.3-0.5% rise in infection cases among that group (Figure 2). We rule out alternative explanations—reporting differences in trade data, exporters’ incentive to misreport, as well as local testing intensity—that might create a spurious relationship between missing imports and the transmission of infectious animal diseases.

Figure 2: Percentage change in the number of infection cases reported by an importing country, by HS4 live animal category

Notes: The figure shows the percentage increase in the number of infection cases reported by an importing country that affect an HS4 live animal category corresponding to a 1% increase in missing imports, or trade discrepancies, across econometric models that include different combinations of control variables. Black dots represent the size of the percentage change while the bar represents the 90 percent confidence interval. The HS4 live animal categories correspond as follows: Est1 (horses, asses, mules and hinnies), Est2 (bovine animals), Est3 (swine), Est4 (sheep and goats), Est5 (poultry, fowls of the species Gallus domesticus, ducks, geese, turkeys and guinea fowls), and Est6 (live animals not elsewhere classified).

How does illicit animal trade spread disease?

We also look at how illicit trade could spread diseases. Practices such as misclassification of species and misdeclaration of consignment value are some of the methods by which live animal species are trafficked (Wyatt et al. 2018). We rely on proxies to identify product categories that are more likely evaded using these practices (Fisman and Wei 2004, Javorcik and Narciso 2008, Rotunno and Vézina 2013), and find that the link between missing imports and infection cases is stronger for product categories that are likely to be misclassified or whose unit prices can be underreported, hinting to the role of specific smuggling practices in spreading diseases.

Policy measures against the spread of disease via illicit animal trade

Is there a way to combat the spread of infectious diseases through illicit animal trade? We analyse two types of preventative measures: border inspection of imported animal species, and regular screening and surveillance of local animal populations. We find that countries employing border inspections more intensively on a live animal category tend to report fewer infection cases among that group, while behind the border measures have no significant impact. Border inspections can therefore be an effective policy tool to combat the spread of infectious diseases through illicit animal trade.

Our research shows that evasive practices in commercial live animal trade are systematically linked to infectious diseases in associated animal species. Robust border inspections effectively curb this impact, offering a practical tool to combat the spread of animal diseases through illicit live animal trade, and therefore to mitigate the associated negative welfare effects. Generally, measures that reduce tax evasion practices, such as simplifying customs procedures (Beverelli and Ticku 2022), may also help to temper the cross-border transmission of animal diseases.

References

Antràs, P, S J Redding, and E Rossi-Hansberg (2023), “Globalization and pandemics”, American Economic Review, 113(4): 939–981.

Beltran-Alcrudo, D, L Falco, T Raizman, and G Dietze (2019), “Transboundary spread of pig diseases: The role of international trade”, Transboundary and Emerging Diseases, 66(3): 1071–1085.

Beverelli, C and R Ticku (2022), “Reducing tariff evasion: The role of trade facilitation”, Journal of Comparative Economics, 50(2): 534–554.

Beverelli, C and R Ticku (2025), “Illicit animal trade and infectious diseases”, World Development, 191: 106969.

Fisman, R and S-J Wei (2004), “Tax rates and tax evasion: Evidence from ‘missing imports’ in China”, Journal of Political Economy, 112(2): 471–496.

Fisman, R and S-J Wei (2009), “The smuggling of art, and the art of smuggling: Uncovering the illicit trade in cultural property and antiques”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1(3): 82–96.

Javorcik, B and G Narciso (2008), “Differentiated products and evasion of import tariffs”, Journal of International Economics, 76(2): 208–222.

Karesh, W B, R A Cook, E L Bennett, and J Newcomb (2005), “Wildlife trade and global disease emergence”, Emerging Infectious Diseases, 11(7): 1000–1002.

Lin, F, X Wang, and M Zhou (2022), “How trade affects pandemics? Evidence from severe acute respiratory syndromes in 2003”, The World Economy, 45(7): 2270–2283.

Lybbert, T, C Barrett, J McPeak, and W Luseno (2004), “Bayesian herders: Updating of rainfall beliefs in response to external forecast”, World Development, 35(3): 480–497.

Murphy, S and L Allen (2003), “Nutritional importance of animal source foods”, Journal of Nutrition, 133(11 Suppl 2): 3932S–3935S.

Oster, E (2012), “Routes of infection: Exports and HIV incidence in Sub-Saharan Africa”, Journal of the European Economic Association, 10(5): 1025–1058.

Rotunno, L and P-L Vézina (2013), “Chinese networks and tariff evasion”, The World Economy, 35(12): 143–164.

Rotunno, L and P-L Vézina (2017), “Israel’s open-secret trade”, Review of World Economics, 153: 233–248.

Santos, P and C Barrett (2011), “Persistent poverty and welfare traps in western Kenya”, Journal of Development Studies, 47(2): 250–267.

Vézina, P-L (2015), “Illegal trade in natural resources: Evidence from missing exports”, International Economics, 141: 103–109.

Wyatt, T, K Johnson, L Hunter, R George, and R Gunter (2018), “Corruption and wildlife trafficking: Three case studies involving Asia”, Asian Journal of Criminology, 13: 35–55.

[1] Discrepancies in mirror trade statistics might arise because exports are recorded as free on board (FOB) while imports include the cost of insurance and freight (CIF), and the recording convention may create discrepancies.