Despite fears that devolving control over forest resources to local communities may accelerate deforestation and worsen the climate crisis, the large-scale transfer of political power to India’s historically marginalised Scheduled Tribes significantly enhanced forest conservation.

Deforestation and forest degradation accelerate climate change, contributing 10-15% of global carbon emissions (Asner et al. 2010). Worldwide, approximately 1.6 billion people rely on forests for their livelihoods (The Global Forest Goals Report 2021). Since the 1970s, policies aimed at decentralising forest governance have sought to balance conservation efforts with the economic needs of marginalised, forest-dependent communities (Andersson et al. 2006). These policies delegate power to local communities for forest management and conservation. However, whether increased local control by local communities leads to more or less environmental conservation overall is an open question.

Understanding what makes decentralisation policies effective for conservation

Existing research has explored the political and economic effects of decentralising political authority but has found mixed evidence on its impact on environmental outcomes when political power is vested in marginalised, forest-dependent communities. This is significant from a policy perspective, as indigenous populations—despite comprising only 5% of the global population—manage a quarter of the Earth’s land surface and sustain 80% of its biodiversity, including forests (Garnett et al. 2018).

Understanding the conditions under which decentralisation policies are most effective at conservation is also theoretically important. Decentralised institutional arrangements transfer power from central to local governments and subsequently to lower-level actors who are directly accountable to rural communities (Agrawal and Ribot 1999). Accessing political power can enable marginalised communities to better pursue their own interests, which are likely to be aligned with forest conservation. However, decentralisation without addressing underlying power imbalances risks elite capture (Bardhan and Mookherjee 2000). Thus, reforms that provide both 'teeth' (enforcement power) and 'voice' (representation) to these communities are likely to be most effective (Fox 2015).

Political representation at the local level in India

India provides an excellent opportunity to study how political representation affects forest conservation. The Indian Constitution mandates political representation for historically disadvantaged communities, including, but not limited to, the reservation of parliamentary and state assembly seats for individuals associated with the Scheduled Tribes ethnic identity category. The decentralisation reforms of 1992, enacted through the 72nd and 73rd Constitutional Amendments, established a third tier of governance. These reforms mandated reservations for Scheduled Tribes at the district, block, and village levels within local councils (or panchayats).

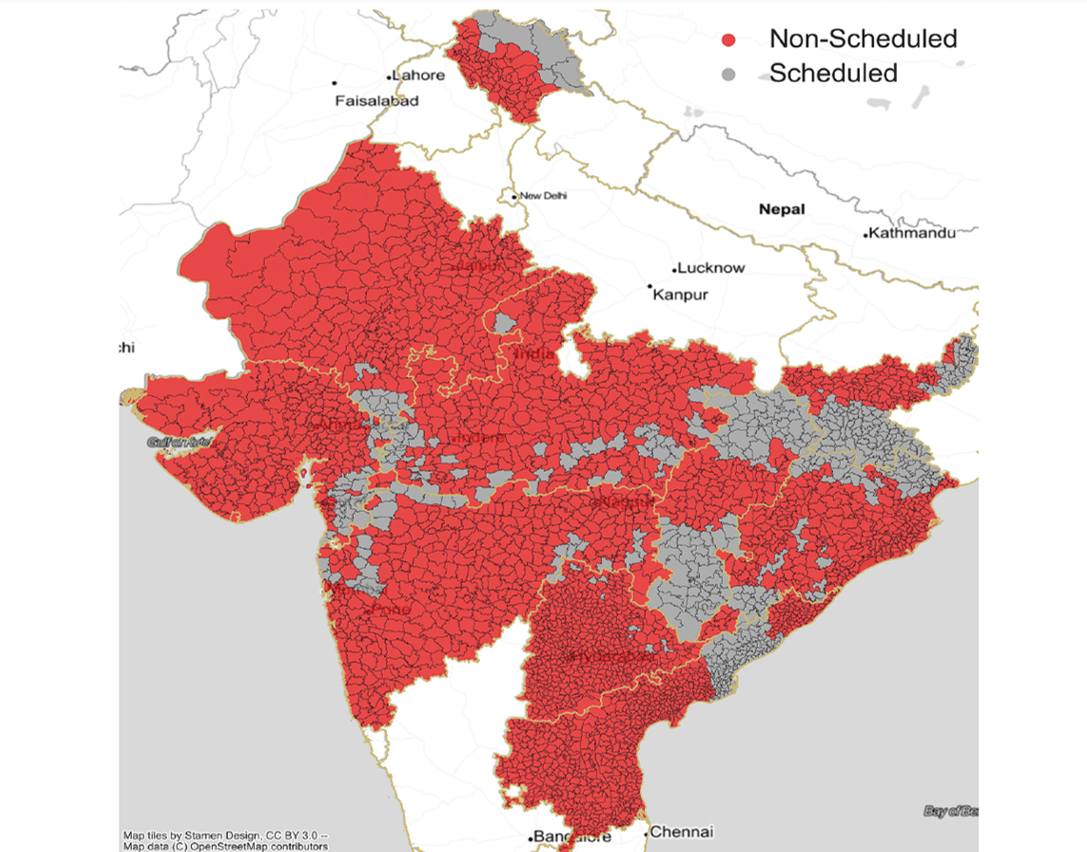

Figure 1: Scheduled Areas in states covered by the fifth schedule of the Indian Constitution

In 1996, The Panchayat Extension to Scheduled Areas (PESA) Act mandated representation for Scheduled Tribes to Scheduled Areas. Scheduled Areas, listed under the Fifth Schedule of the Indian Constitution, are predominantly rural, sparsely populated, and historically marked by limited economic and political opportunities for their inhabitants. The President of India has the authority to declare villages, blocks, or entire districts as Scheduled Areas, many of which were originally designated by the colonial government before India’s independence in 1947.

Moving beyond the Constitutional Amendments, PESA devolved additional governance powers to village councils and reserved 50% of local council seats, as well as the leadership positions on these councils, to Scheduled Tribes on a permanent basis.

Measuring how increased representation of minority tribes affected forest outcomes

Estimating the causal effects of changes in political institutions on forest outcomes is challenging because such changes are often implemented across large administrative units or targeted at areas with unique characteristics. These factors complicate the construction of suitable counterfactuals, making it difficult to attribute observed effects directly to institutional change. However, the increased representation of Scheduled Tribes under PESA, within already established Scheduled Areas, provides a unique opportunity to evaluate the impact of increased representation on forest outcomes.

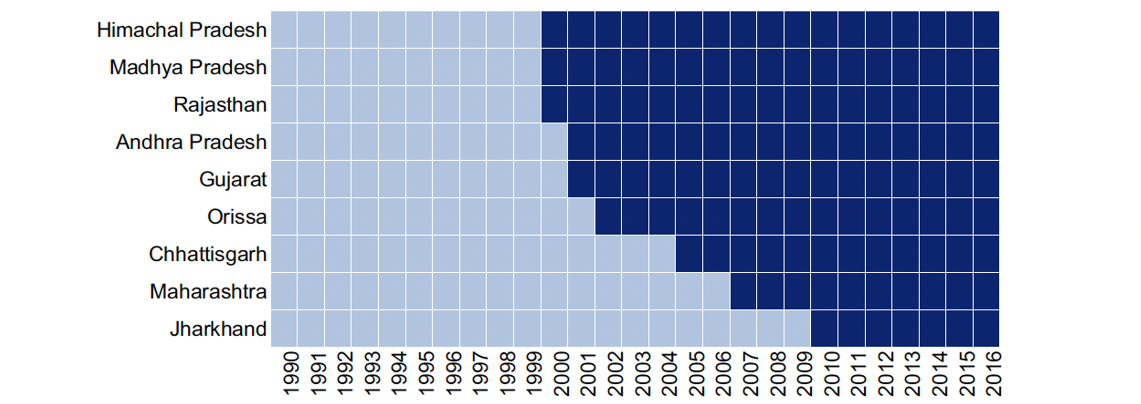

PESA was implemented by states in a staggered manner beginning in 2000. We create a switching indicator for Scheduled Areas, in each state, based on the occurrence of the first panchayat election in Scheduled Areas in accordance with PESA.

Figure 2: Panchayat extension to Scheduled Areas (PESA) Act implementation timing

Notes: Darker shades indicate years with PESA implementation. PESA was implemented only in Scheduled Areas within each of these states. Vegetation Continuous Fields data are available for the entire period. Global Forest Cover data are only available from 2001.

Using this, we employ a difference-in-differences framework to isolate the causal effect of Scheduled Tribe-mandated representation on forest outcomes. This approach leverages the staggered adoption of PESA institutions across states and within-state variation between Scheduled and non-Scheduled Areas. The first difference is between Scheduled Areas and non-Scheduled Areas wtihin the same state, and the second is over-time variation following the implementation of PESA in Scheduled Areas.

We use two remote sensing datasets to measure forest cover and deforestation. For forest cover we use the MEaSURES VCF dataset (Song et al. 2018) which reports annual tree-canopy cover, non-tree vegetation, and bare ground from 1982 to 2016. For deforestation, we use the GFC dataset (Hansen et al. 2013). We aggregate these measures to the village level and calculate the local areas of deforestation by converting the deforested pixels into hectares per village-year.

Mandated representation enables Scheduled Tribes’ to voice their opinions in local governance

Our main finding is that boosting formal representation for Scheduled Tribes via PESA led to an average increase of tree canopy by 3%, per year, as well as a reduction in the rate of deforestation. The effects are larger for areas that had more forest cover at the start of the study period. We further show that our observed effects arise only after the introduction of PESA elections that mandate representation for Scheduled Tribes.

Next, we compare the impacts of PESA legislation with other legal reforms that institute some, but not all, elements of PESA. We find that the staggered arrival of local government, absent mandated representation for Scheduled Tribes, had no discernable effects on forest outcomes. In addition, the implementation of the Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006 (or Forest Rights Act)—which was intended to bolster Scheduled Tribes rights to forest lands—had no discernible additional impacts beyond those caused by PESA.

These results point to the key role of mandated representation in enabling Scheduled Tribes communities’ voice in local governance: neither local representation, nor the legal provision of forest rights, were themselves sufficient—only with a boost in Scheduled Tribes communities’ political power did we see an increase in forest conservation. They also help explain the mixed evidence in previous work.

Finally, we present three pieces of suggestive evidence that increasing ST representation enabled these communities to resist mining and other large-scale commercial operations. First, areas that are close to mines, prior to the implementation of PESA, experienced high rates of deforestation. Second, the introduction of PESA elections led to a greater reduction in deforestation for PESA villages close to mines. Third, using new data from Land Conflict Watch (2022), we present causal evidence that the introduction of PESA increased the incidence of conflict around mining. Taken together, these results suggest organised protests against large-scale mining operations are an important channel of change.

Mandated representation institutions can help support development and conservation

Forest-dependent communities rely on the small-scale collection of non-timber forest products for economic security. Granting these communities greater political power can enable them to better advocate for, and mobilise around, their political and economic interests, including forests conservation.

Our findings demonstrate that establishing and empowering a single umbrella institution for such communities —through mandated representation in village council governance under PESA—helps these communities balance forest conservation with sustainable extraction of non-timber forest products. Increased local political power not only enhances Scheduled Tribes’ forests stewardship but also strengthens their ability to resist commercial pressures seeking large-scale exploitation of forest resources.

Over a hundred countries around the world have implemented mandated representation institutions with the aim of bolstering the voice of marginalised communities. Our previous work shows that the same institution, PESA, also enabled Scheduled Tribes’ communities to improve their economic opportunities via NREGA and the provision of local public goods (Gulzar et al. 2020). We recommend further scholarly and policy focus on political representation as an umbrella institution channel for balancing the dual policy objectives of development and conservation.

References

Agrawal, A, and J Ribot (1999), “Accountability in decentralization: A framework with South Asian and West African cases,” The Journal of Developing Areas, 33(4): 473–502. Available at: https://experts.illinois.edu/en/publications/accountability-in-decentralization-a-framework-with-south-asian-a.

Andersson, K P, C C Gibson, and F Lehoucq (2006), “Municipal politics and forest governance: Comparative analysis of decentralization in Bolivia and Guatemala,” World Development, 34(3): 576–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.08.009.

Asner, G P, G V N Powell, J Mascaro, D E Knapp, J K Clark, J Jacobson, T Kennedy-Bowdoin, A Balaji, G Paez-Acosta, E Victoria, L Secada, M Valqui, and R F Hughes (2010), “High-resolution forest carbon stocks and emissions in the Amazon,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(38): 16738–16742. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1004875107.

Bankar, S, M Collumbien, M Das, R K Verma, B Cislaghi, and L Heise (2018), “Contesting restrictive mobility norms among female mentors implementing a sport-based programme for young girls in a Mumbai slum,” BMC Public Health, 18: 471.

Bardhan, P, and D Mookherjee (2000), “Capture and governance at local and national levels,” American Economic Review, 90(2): 135–139. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.90.2.135.

Baysan, C (2022), “Persistent polarizing effects of persuasion: Experimental evidence from Turkey,” American Economic Review, 112(11): 3528–3546.

Burke, M, J Ferguson, S Hsiang, and E Miguel (2024), “New evidence on the economics of climate and conflict,” NBER Working Paper No. w33040. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3386/w33040.

Deshpande, A, and J Singh (2021), “Dropping out, being pushed out or can’t get in? Decoding declining labour force participation of Indian women,” IZA Discussion Paper No. 14639. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3905074 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3905074.

Enikolopov, R, M Petrova, and E Zhuravskaya (2011), “Media and political persuasion: Evidence from Russia,” American Economic Review, 101(7): 3253–3285.

Fetzer, T (2020), “Can workfare programs moderate conflict? Evidence from India,” Journal of the European Economic Association, 18(6): 3337–3375. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvz062.

Fox, J A (2015), “Social accountability: What does the evidence really say?” World Development, 72: 346–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.03.011.

Garnett, S T, N D Burgess, J E Fa, Á Fernández-Llamazares, Z Molnár, C J Robinson, J E M Watson, et al. (2018), “A spatial overview of the global importance of indigenous lands for conservation,” Nature Sustainability, 1(7): 369.

Gessen, M (2017), The Future Is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia, Riverhead Books.

Goel, R (2023), “Gender gap in mobility outside home in urban India,” Travel Behaviour and Society, 32: 100559.

Gulzar, S, N Haas, and B Pasquale (2020), “Does political affirmative action work, and for whom? Theory and evidence on India’s scheduled areas,” American Political Science Review, 114(4): 1230–1246.

Gulzar, S, A Lal, and B Pasquale (2024), “Representation and forest conservation: Evidence from India’s scheduled areas,” American Political Science Review, 118(2): 764–783.

Huntington, S P (1997), The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, Simon and Schuster.

Kabeer, N (1999), “Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment,” Development and Change, 30(3): 435–464.

Kabeer, N, S Mahmud, and S Tasneem (2011), “Does paid work provide a pathway to women’s empowerment? Empirical findings from Bangladesh,” Working Paper.

Kessler, J B, and K L Milkman (2016), “Identity in charitable giving,” Management Science, 64(2): 845–859.

Land Conflict Watch (2022), “Conflicts Database,” Available at: https://www.landconflictwatch.org/about.

Mitter, R, and E Johnson (2021), “What the West gets wrong about China: Three fundamental misconceptions,” Harvard Business Review, 99(3): 42–48.

Nandwani, B, and P Roychowdhury (2024), “Rural road infrastructure and women’s empowerment in India,” The World Bank Economic Review, lhae048.

Peisakhin, L, and A Rozenas (2018), “Electoral effects of biased media: Russian television in Ukraine,” American Journal of Political Science, 62(3): 535–550.

Rogall, T, and A Guariso (2017), “About ethnic conflicts, inequality, and rainfall in Africa,” VoxEU, April 4.

Shrinivas, A, K Baylis, and B Crost (2024), “Food transfers and child nutrition: Evidence from India’s Public Distribution System,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, forthcoming.

The Constitution (Seventy-third Amendment) Act, 1992 | National Portal of India (n.d.), Available at: https://www.india.gov.in/my-government/constitution-india/amendments/constitution-india-seventy-third-amendment-act-1992.

The Global Forest Goals Report 2021 (2021), Available at: https://doi.org/10.18356/9789214030515.

United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, and M Singh (n.d.), “Panchayat (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996,” in socialissuesindia.wordpress.com, pp. 3–16. Available at: https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/PESAAct1996_0.pdf.

WaterAid (2013), “We can’t wait: A report on sanitation and hygiene for women and girls,” WaterAid International. Available at: http://www.zaragoza.es/contenidos/medioambiente/onu/1325-eng_We_cant_wait_sanitation_and_hygiene_for_women_and%20girls.pdf.