A community-led water, sanitation, and hygiene programme in the Democratic Republic of Congo improved access but was unable to protect child health. Evidence suggests that more investment in water quality may be necessary to reduce diarrheal diseases and improve child growth.

Recent estimates suggest that improving water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) could prevent 1.4 million deaths each year (Wolf et al. 2023). People living with unsafe WASH ingest faecal material, resulting in enteric dysfunction and child growth faltering, which have long-term negative impacts on health, cognition, and human capital (Grantham-McGregor et al. 2007, Black et al. 2017).

The need for improved WASH is enormous (Dupas 2024). As of 2020, two billion people did not have access to safely managed drinking water services, 3.6 billion did not have access to safely managed sanitation services, and 2.3 billion did not have access to handwashing facilities with soap and water at home (Prüss-Ustün et al. 2019, WHO 2021). While WASH access has increased with time, this progress must be accelerated by three-to-sixfold in order to meet UN Sustainable Development Goals by 2030 (WHO/UNICEF JMP 2023).

To increase access to safe WASH, governments and donors have increasingly turned to community-led approaches. Beginning with community-led total sanitation in Bangladesh in 1999, community-led WASH programmes have been implemented in at least 60 countries; and 15 countries have incorporated them into national policy (Pickering et al. 2015, Whittington et al. 2020).

Despite this broad adoption, the health effects of WASH interventions (community-led and otherwise) remain poorly understood (Augsburg et al. 2024, Motohashi 2023). The length of the causal chain from intervention to outcome and the vast design space for WASH interventions (which can incorporate behaviour change campaigns, infrastructure, institutional support, and/or new technologies), mean that many fundamental questions remain unanswered. A meta-analysis of 13 randomised WASH trials found no effect on child length-for-age, but a meta-analysis of 124 WASH studies (randomised and observational) found a protective effect against diarrhoea (Bekele et al. 2020, Wolf et al. 2022). Results vary markedly across studies, likely due to variation in intervention components and intensity, and to the influence of contextual factors such as baseline exposure to faecal matter.

Introducing a community-led WASH programme in the DRC

The Healthy Villages and Schools programme differs from other WASH interventions used in randomised trials, combining a community-led approach to behaviour change, support for new WASH institutions, and implementation of subsidies for water and sanitation infrastructure. The programme mobilised communities to become ‘Healthy Villages’ following three to six months of support from government health officials and local NGOs, which included approximately US$2,000 of financing for new or improved water infrastructure, US$2,000 for new or improved sanitation infrastructure, plus US$3,000 for personnel costs, per village. This initiative was co-led by the Ministries of Public Health, and Primary, Secondary, and Professional Education, with support from UNICEF. From 2008 to 2020, the programme reached nearly nine million people in almost 11,000 villages, making it the largest WASH programme implemented by UNICEF globally, as well as the largest rural WASH in the DRC from 2005 to 2020 (World Bank 2017).

Figure 1: The steps of the Healthy Villages component of the Healthy Villages & Schools

Note: Village Assaini translates to ‘healthy village’.

The Healthy Villages & Schools programme increased access to improved water and sanitation, and created lasting institutions

In our study, 121 groups of villages were randomly assigned to either receive the program or to be in the control group. We visited villages about three and a half years after programme completion to interview residents, measure child growth, and test water quality.

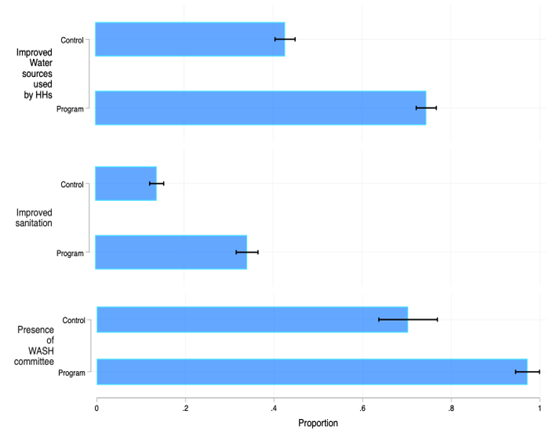

Among programme villages, 96% reported that they created a community action plan and prioritised actions to improve WASH (as instructed by the programme), while 86% reported that they had implemented that plan. This is remarkably high adherence for a programme implemented at scale in a country with ongoing armed conflict and poor infrastructure. Among programme villages, 99% reported the presence of a committee that actively manages WASH, compared to 69% of control villages.

Households in the programme group were 24 percentage points more likely to report using an improved water source than the control group. Most improved sources were protected springs or public taps. Households in the programme group were also 18 percentage points more likely to report using an improved sanitation facility (typically a latrine with a concrete slab and cover), and reported more positive perceptions of water governance, including satisfaction with water access. Programme households were also 9 percentage points more likely to report paying for water. Conditional on paying for water, there was no difference in the amount paid between the intervention and control groups. The programme had no effect on time spent collecting water.

In structured observations of handwashing behaviour, there was no difference between programme and control households in measures of any observed handwashing or handwashing with soap or ash.

Figure 2: Access to improved water source, improved sanitation facility, and presence of WASH committee, in programme versus control villages

The Healthy Villages & Schools programme did not protect child health

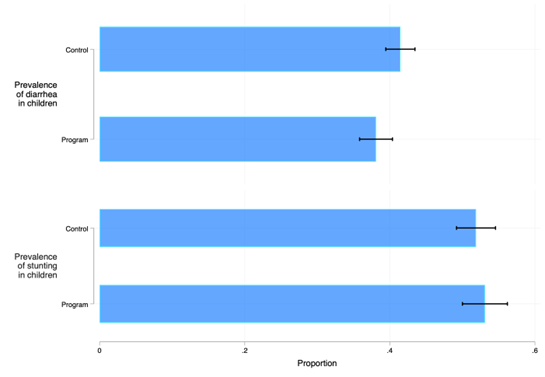

Diarrhoea prevalence was high overall, at 38% in the programme group and 42% in the control group. The programme had no effect on diarrhoea. The programme had no effect on length-for-age Z-scores in children.

Figure 3. Diarrhoea and stunting (child’s height is far below typical for their age), in programme versus control villages

Water quality is likely the reason that child health did not improve

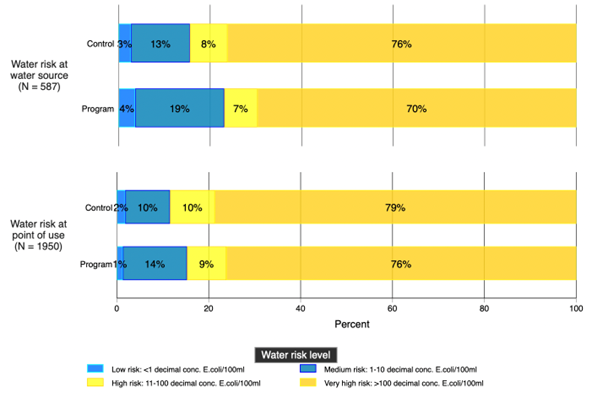

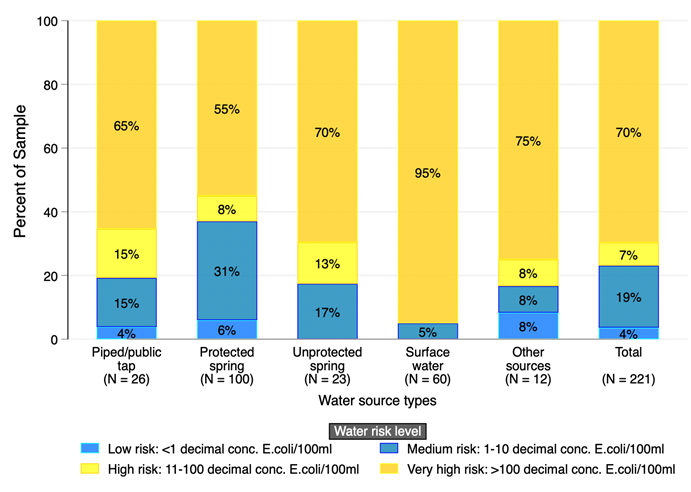

Water samples from programme village water points showed a small but statistically significant improvement in thermotolerant coliforms per 100mL (an indicator of contamination) compared to control village samples. Overall water quality was low, even from improved sources. Among unimproved sources, 86% of samples had coliform levels over 100 per 100mL, or ‘very high risk’ according to WHO standards (WHO 2004); among improved sources, 60% of samples had coliform levels over 100 per 100mL. Water samples from programme household water containers showed no difference in thermotolerant coliforms per 100mL compared to control household samples.

Figure 4: Water contamination level at source and at point of use, in programme versus control villages

Figure 5: Water contamination level by water source type, in programme villages

More ambitious WASH policies will be necessary to improve child health

In addition to our study, several recent experiments have shown that increased access to improved water and sanitation infrastructure is often insufficient to protect children from illness. As a result, many researchers call for a more ambitious ‘transformative WASH’ approach. This could involve “high community coverage of improved sanitation facilities, complete separation of animal faeces from people’s living environments, continuous and convenient access to uncontaminated water, reductions in faecal contamination on surfaces where young children crawl and play, new technologies to deliver WASH services which might differ from those implemented in high-income countries, or different modalities of behaviour change” (Pickering et al. 2019, Gertler et al. 2020). Chlorination at point-of-collection or through vouchers is one promising tool, as is real-time monitoring of water source breakdowns (Kremer et al. 2023, Hope 2024, Bhalotra et al. 2022, Dupas et al. 2022). Business as usual is not enough.

References

Augsburg, B., Foster, A., Lipscomb, M., Rahut, D., Seetharam, K. E., & Sonobe, T. (2024), "Policy lessons from new advances in sanitation economics", VoxDev.

Bekele, T., Rawstorne, P., & Rahman, B. (2020), "Effect of water, sanitation and hygiene interventions alone and combined with nutrition on child growth in low and middle income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis", BMJ Open, 10(7): e034812.

Bhalotra, S., Diaz-Cayeros, A., Miller, G., Miranda, A., & Venkataramani, A. (2022), "Urban water disinfection and mortality decline: Evidence from Mexico", VoxDev.

Black, M. M., Walker, S. P., Fernald, L. C., Andersen, C. T., DiGirolamo, A. M., Lu, C., McCoy, D. C., et al. (2017), "Early childhood development coming of age: Science through the life course", The Lancet, 389(10064): 77–90.

Dupas, P., Nhlema, B., Wagner, Z., Wolf, A., & Wroe, E. (2022), "Expanding access to clean water for the rural poor: Evidence from Malawi", VoxDev.

Dupas, P. (2024), "Improving access to and usage of clean water", VoxDev.

Gertler, P., Coville, A., & Galiani, S. (2020), "Pipe dreams: Enforcing payment for water and sanitation services in Kenya", VoxDev.

Grantham-McGregor, S., Cheung, Y. B., Cueto, S., Glewwe, P., Richter, L., Strupp, B., & International Child Development Steering Group (2007), "Developmental potential in the first 5 years for children in developing countries", The Lancet, 369(9555): 60–70.

Hope, R. (2024), "Four billion people lack safe water", Science, 385(6710): 708–709.

Kremer, M., Luby, S. P., Maertens, R., Tan, B., & Więcek, W. (2023), "Water treatment and child mortality: A meta-analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis", Unpublished manuscript.

Motohashi, K. (2023), "Sanitation investments, water pollution and health: Lessons from India", VoxDev.

Pickering, A. J., Djebbari, H., Lopez, C., Coulibaly, M., & Alzua, M. L. (2015), "Effect of a community-led sanitation intervention on child diarrhoea and child growth in rural Mali: A cluster-randomised controlled trial", The Lancet Global Health, 3(11): e701–11.

Prüss-Ustün, A., Wolf, J., Bartram, J., Clasen, T., Cumming, O., Freeman, M. C., Gordon, B., Hunter, P. R., Medlicott, K., & Johnston, R. (2019), "Burden of disease from inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene for selected adverse health outcomes: An updated analysis with a focus on low- and middle-income countries", International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 222(5): 765–77.

Whittington, D., Radin, M., & Jeuland, M. (2020), "Evidence-based policy analysis? The strange case of the randomized controlled trials of community-led total sanitation", Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 36(1): 191–221.

WHO (2004), "Guidelines for drinking-water quality", World Health Organization.

WHO (2021), "Progress on household drinking water, sanitation and hygiene 2000-2020: Five years into the SDGs", World Health Organization.

WHO/UNICEF JMP (2023), "Progress on household drinking-water, sanitation and hygiene 2000-2022: Special focus on gender", WHO/UNICEF JMP.

Wolf, J., Hubbard, S., Brauer, M., Ambelu, A., Arnold, B. F., Bain, R., Bauza, V., et al. (2022), "Effectiveness of interventions to improve drinking water, sanitation, and handwashing with soap on risk of diarrhoeal disease in children in low-income and middle-income settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis", The Lancet, 400(10345): 48–59.

Wolf, J., Johnston, R. B., Ambelu, A., Arnold, B. F., Bain, R., Brauer, M., Brown, J., Caruso, B. A., Clasen, T., & Colford, J. M. (2023), "Burden of disease attributable to unsafe drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene in domestic settings: A global analysis for selected adverse health outcomes", The Lancet, 401(10393): 2060–71.

World Bank (2017), "WASH poor in a water-rich country: A diagnostic of water, sanitation, hygiene, and poverty in the Democratic Republic of Congo".