As global conflicts grow, new evidence from Afghanistan shows that girls exposed to war violence in utero suffer long-term setbacks in learning and development. Addressing these hidden costs of conflict must be part of any strategy for peace and reconstruction.

War leaves behind more than shattered buildings and displaced communities. Beyond the visible damage—lost lives, economic collapse, and destroyed infrastructure—conflict also inflicts quieter, longer-lasting harm. These hidden costs often fall heaviest on the most vulnerable: women and children (Akbulut-Yuksel et al. 2022, Brück et al. 2019). Among them, unborn children are especially at risk. Emerging evidence shows that violence and instability during pregnancy can disrupt foetal development in ways that have lifelong consequences, affecting a child’s health (Almond and Mazumder 2011, Currie et al. 2023), learning (Black et al. 2007), and future economic opportunities (Currie 2011).

A growing body of research shows that early-life exposure to adversity can have lasting impacts. Yet, we know little about how violence during pregnancy shapes children’s long-term development, especially in fragile, gender-unequal settings like Afghanistan. In Aslim et al. (2025), we investigate how exposure to conflict during pregnancy affects children’s cognitive and developmental outcomes years later. We focus on foundational indicators of human capital, such as school attendance, math performance, and functional difficulties, to understand how conflict experienced in the womb may shape a child’s future. We examine this question in the context of Afghanistan, a country deeply affected by decades of violent conflict.

Mapping prenatal exposure to war in Afghanistan

Afghanistan offers a uniquely important setting to study the long-term impacts of prenatal exposure to war. The country has endured more than four decades of violent conflict, marked by recurring cycles of insurgency, foreign intervention, and internal instability. Alongside persistent poverty, limited access to health and education services, and deeply entrenched gender inequality, the burden of conflict has fallen disproportionately on women and children. Against this backdrop, we use novel geo-referenced data on violent incidents and restricted survey data on children’s human capital outcomes to explore how exposure to violence before birth affects development.

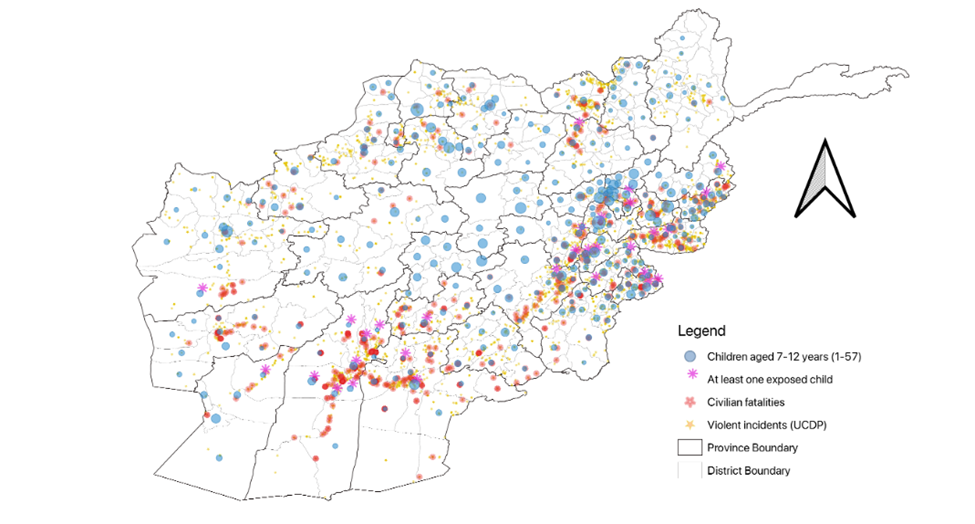

We map the geography of conflict and exposure across the country. Figure 1 shows violent incidents involving civilian fatalities from 2009 to 2016, overlaid with data on children aged 7–12 for whom we observe educational and cognitive outcomes. While some areas, such as Kabul, report higher child counts, the map reveals that civilian casualties are dispersed even in districts with little sustained conflict. This randomness underscores how exposure to war violence, even in utero, can cut across geographic and social boundaries, often hitting families without warning.

Figure 1. Spatial distribution of violent incidents and civilian casualties (2009–2016)

Notes: This map shows the spatial coverage of the analytical sample, violent incidents, and civilian casualties by district in Afghanistan from 2009 to 2016. Blue circles represent the number of surveyed children in the analytical sample aged 7–12 years, red markers indicate districts with reported civilian casualties, purple stars denote districts where children were exposed to fatalities in utero, and yellow stars mark violent incidents. The map is constructed by the authors based on data from the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS)–Afghanistan and the Uppsala Conflict Data Program.

To estimate the long-term impact of being exposed to war violence before birth, we exploit the spatial and temporal variation in violent conflicts, as shown in the map. Specifically, we identify whether children aged 7–12 were in the womb during a civilian casualty event in their district. By comparing children of the same age living in the same province, where one was exposed to violence in utero and another was not, we isolate the effect of prenatal war exposure. Our analysis accounts for a wide range of individual, household, and local characteristics, and includes fixed effects to control for unobserved differences across provinces and age groups.

Prenatal exposure to war disrupts learning

We find that children exposed to civilian casualties in the womb are significantly less likely to attend school. Specifically, children exposed in utero are about 8.5% less likely to have ever attended school. However, we find no statistically significant effect on current grade level or on performance in math for the overall sample. Similarly, in utero exposure does not significantly affect reported functional difficulties or experiences of physical punishment, though the estimated effects move in the expected direction.

For comparison, children exposed to war violence after birth (up to the time of survey) are also about 8.5% less likely to have ever attended school. In contrast to in utero exposure, post-birth exposure is associated with a small but statistically significant decline in math performance, but no significant impact on other developmental outcomes.

Girls bear the brunt of being in utero during conflict

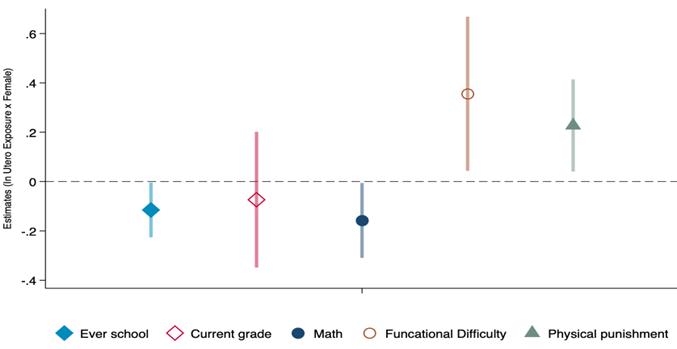

The overall effects mask substantial gender disparities. Specifically, our gender-specific analysis shows that in utero exposure to war conflict has no statistically significant impact on educational or developmental outcomes among boys. In contrast, exposed girls experience significantly worse outcomes across all measures. As shown in Figure 2, girls exposed to war conflict in utero are about 15% less likely to attend school compared to boys. They also score 0.16 standard deviations lower in math, with the decline concentrated in basic number recognition and addition tasks. These skills are fundamental to early cognitive development and may be particularly vulnerable to disruption during pregnancy.

Figure 2: Effects of in utero exposure to war conflict on girls relative to boys

Note: Bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

The developmental impacts are also stark. Girls exposed to violence in utero face a 0.36 standard deviation increase in functional difficulties, especially in areas related to cognition. They also experience a 0.23 standard deviation increase in physical punishment compared to boys. These patterns suggest that prenatal exposure may exacerbate existing gender inequalities in Afghanistan, where girls already face significant barriers to education and well-being.

Why are girls hit harder by prenatal exposure to conflict?

One reason girls suffer more may be household responses to economic strain. We find that households exposed to violence during pregnancy had significantly lower asset levels, particularly in higher-value goods such as vehicles and land. This economic depletion, combined with prevailing patriarchal norms, likely shaped how families allocated limited resources in the years following exposure. In such settings, parents may prioritise boys’ education and well-being over girls, unintentionally deepening the developmental toll on daughters. While we do not observe clear differences in adult employment or ownership between exposed and unexposed households, the decline in household wealth suggests that conflict-related shocks can reinforce gender gaps in human capital investment.

Policy implications for conflict-affected regions

The long-term effects of war conflict are not just written in headlines or history books—they are etched into the lives of children before they are even born. Our findings show that prenatal exposure to war violence in Afghanistan had lasting effects on girls’ education and development, while boys are largely spared. In conflict-affected regions, where poverty and gender inequality are already entrenched, such shocks can deepen disadvantage and limit recovery across generations. As conflicts continue to expose millions of children to early-life trauma, the risks we identify in Afghanistan are increasingly global. Policies that support maternal health, strengthen household resilience, and promote equitable access to education are more critical than ever. Addressing the hidden costs of war, especially those borne by girls, must be part of any strategy for peace and reconstruction.

References

Akbulut-Yuksel, M, E Tekin, and B Turan (2022), “World War II blues: The long–lasting mental health effect of childhood trauma,” Unpublished manuscript.

Almond, D, and B Mazumder (2011), “Health capital and the prenatal environment: The effect of Ramadan observance during pregnancy,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 3(4): 56–85.

Aslim, E G, R Najam, and E Tekin (2025), “Human capital impacts of in utero exposure to war conflict in Afghanistan,” Unpublished manuscript.

Black, S E, P J Devereux, and K G Salvanes (2007), “From the cradle to the labor market? The effect of birth weight on adult outcomes,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(1): 409–439.

Brück, T, M Di Maio, and S H Miaari (2019), “Learning the hard way: The effect of violent conflict on student academic achievement,” Journal of the European Economic Association, 17(5): 1502–1537.

Currie, J (2011), “Inequality at birth: Some causes and consequences,” American Economic Review, 101(3): 1–22.

Currie, J, B Dursun, M Hatch, and E Tekin (2023), “The hidden cost of firearm violence on infants in utero,” Unpublished manuscript.