Evidence from Mexico City shows training enhances officer interactions with citizens and reduces harmful conduct, providing valuable insights for improving frontline services.

Every day, frontline public servants make countless judgement calls that shape how citizens experience government services and influence trust in institutions (Lipsky 2010). A teacher decides how to adapt the curriculum to suit the needs of diverse learners. A social worker decides how to prioritise support services. A nurse decides how to allocate limited time among patients. While organisational routines and guidelines provide structure to these decisions, employees must rely on their discretion to navigate difficult situations. This is especially true for the police, where the wide range and emotionally charged nature of encounters between officers and citizens cannot be reduced to programmed formats.

For police departments worldwide, officer discretionary decisions—from determining whom to stop and how to communicate, to when force is justified and how it is used—present a fundamental governance challenge. Effective policing inherently relies on community trust and willingness to collaborate in identifying, reporting, and solving crimes. When police exercise their discretion poorly—for example, by misusing their authority—legal cynicism spreads, crime reporting goes down, and public safety suffers (Weitzer 2002, Kirk and Papachristos 2011, Ang et al. 2025).

In most regions of the world, trust in the police has fallen below critical levels (Integrated Values Survey 2022), creating serious challenges for governance and the rule of law. To rebuild citizens trust, police departments must urgently equip officers with practical strategies to prevent misconduct and strengthen community relationships. Our recent research (Canales et al. 2025) evaluates whether targeted training can enhance officers’ decision-making on the streets and reduce harmful behaviour in Mexico City.

The importance of procedural justice

When people interact with authority figures such as the police, they often care more about how they are treated than the actual outcome of the encounter. A driver who receives a ticket but feels the officer was respectful and clearly explained the violation may still retain a positive view of law enforcement. Research shows that when people feel they have been treated fairly by authorities, they are more likely to view those authorities as legitimate, comply with their directives, and cooperate with them in the future (Tyler 2006). Conversely, even when let off with a warning, a driver who feels disrespected, unfairly targeted, or even corruptly benefited may develop lasting resentment or scepticism toward the police.

This concept, known as procedural justice, comprises four key elements: giving citizens voice by listening to their concerns and perspectives, demonstrating impartiality in decision-making, treating people with dignity and respect, and explaining actions transparently. While the benefits of procedural justice are well documented (Colquitt et al. 2012, President’s Task Force 2018), evidence on whether such behaviours can be taught effectively remains limited. Can training be a driver for influencing how police officers think and behave in their interactions with the public?

Training as a tool for changing the way police officers think and act

To answer this question, we partnered with Mexico City's Ministry of Citizen Security on a large-scale field experiment involving nearly 1,900 police officers. Half of the officers were randomly assigned to receive a three-day, nine-hour training programme focused on procedural justice (treatment group), while the other half did not receive the training (control group). The training was structured around four key design elements:

- Officer involvement: Former local police officers participated in co-designing both the training content and its delivery to ensure contextual relevance.

- A safe space: The first third of training focused on acknowledging officers' challenges and giving room to express their frustrations—earning their buy-in—before introducing concrete strategies for improving citizen interactions.

- Small groups: Training was delivered to groups of 20 or fewer officers to encourage engagement and active participation.

- Practical approach: Beyond theory, officers were equipped with actionable strategies and practiced them through role-play in realistic scenarios.

To evaluate the training’s effects, we used surveys to measure changes in officer mindsets and approach to policing, and an innovative ‘mystery shopper’ evaluation to assess real-world behavioural changes, in which a group of actors—posing as citizens—interacted with treatment and control police officers. Officers were unaware of the objective of the interaction and did not know they were participating in a simulated encounter until the experiment was completed. Actors recorded the interactions using hidden video and audio devices, which allowed a group of external observers to evaluate officers’ behaviour. The results were compelling on both fronts.

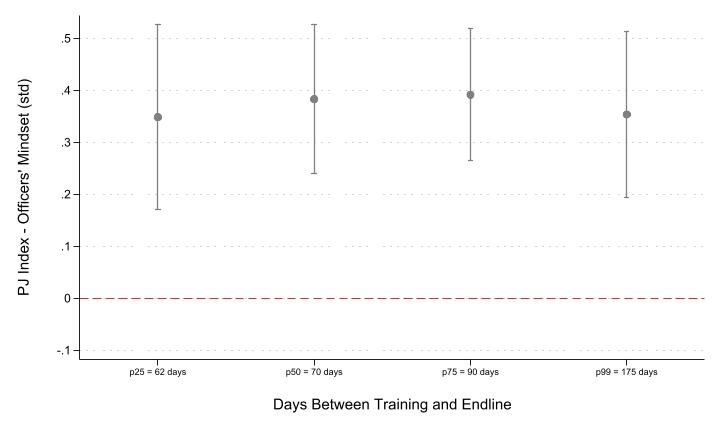

The training reshaped how officers perceive their responsibilities, encouraging a mindset oriented toward fairness, empathy, transparency, and responsiveness to the communities they serve. These improvements persisted even six months after the training, suggesting durable rather than temporary effects.

Figure 1: Training effects on police officers’ procedural justice mindsets

Note: The figures show training effects, measured in standard deviations, at various points in time after the training.

Importantly, these changes were not just limited to internal thoughts, they were reflected in observable behaviour in the streets. Trained officers demonstrated a consistent shift toward more respectful and open communication with the public, accompanied by a notable reduction in dismissive or disengaged conduct. These are exactly the kinds of interactions that lay the groundwork for building trust and strengthening public safety over time.

The role of context in enabling or constraining change

Our findings revealed important patterns in how individual characteristics and environmental factors influenced the training’s effects.

- Officers’ initial attitudes toward citizens influenced their responsiveness to the training: Those with initially more positive attitudes toward citizens showed larger behavioural improvements. Nonetheless, officers with less favourable starting predispositions still experienced meaningful shifts in mindset and reduced their use of harmful behaviours.

- Work environment significantly moderated behavioural change: Officers patrolling higher-crime areas showed smaller behavioural shifts despite similar mindset improvements. This suggests that high-stress environments may make it harder to consistently apply new approaches, even when officers understand and value them.

- Management alignment proved consequential: Officers whose supervisors had also received procedural justice training exhibited greater improvements in mindset. This ‘trickle-down’ effect highlights how organisational culture and leadership signals can either reinforce or undermine training messages.

Beyond policing: Broader lessons for improving frontline services

While our study focused on policing, the findings offer valuable insights for a broad range of public service domains where frontline employees engage with citizens in complex, high-stakes situations requiring discretionary judgment. Sectors such as social services, healthcare, education, and regulatory agencies face similar challenges in promoting respectful and constructive interactions with the public.

Training alone is not a silver bullet. However, when thoughtfully designed, grounded in local context, and supported by leadership and day-to-day organisational practices, it can meaningfully shift how individuals approach their work. For policymakers aiming to improve public service delivery, our research highlights several actionable strategies:

- Fair behaviours can be taught: The ability to treat people justly is not simply an innate personality trait that needs to be recruited—it is a skillset that can be developed through training.

- Training design matters: Small groups, locally relevant content, active engagement, and opportunities for practice appear crucial to training impact. This stands in contrast to conventional corporate training programmes, which are often delivered in large groups, rely on asynchronous modules with minimal engagement, or use generic content that overlooks the specific context or professional realities of participants.

- Organisational practices and incentives must align with the principles being taught: For example, if employees internalise procedural justice but are managed unfairly or rewarded for contradictory behaviours, the benefits of training are unlikely to persist.

- Environmental constraints must be acknowledged and addressed: Frontline workers operating under high stress or frequent adverse interactions may need additional support to consistently translate good intentions into action. This may include refresher training, adjusted shift schedules to prevent burnout, or structural changes to reduce environmental stressors.

For police departments specifically, procedural justice training represents a promising approach to strengthening community relations and improving public safety. But the framework holds equal relevance for other public services. In an era of declining trust in public institutions, efforts to strengthen fairness and transparency in frontline interactions offer a concrete, scalable path to rebuild public trust and enhance government services.

References

Ang, D, P Bencsik, J Bruhn, and E Derenoncourt (2025), “Community engagement with law enforcement after high-profile acts of police violence”, American Economic Review: Insights, 7(1): 124–142.

Canales, R, J F Santini, M González Magaña, and A Cherem (2025), “Shaping police officer mindsets and behaviors: Experimental evidence of procedural justice training”, Management Science.

Colquitt, J A, J Greenberg, and C P Zapata-Phelan (2012), “Organizational justice”, in The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Psychology.

Integrated Values Surveys (2022), “Integrated Values Surveys – with major processing by Our World in Data”.

Kirk, D S and A V Papachristos (2011), “Cultural mechanisms and the persistence of neighborhood violence”, American Journal of Sociology, 116(4): 1190–1233.

Lipsky, M (2010), "Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Service", Russell Sage Foundation.

President’s Task Force (2018), "Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing", Office of Community Oriented Policing Services.

Weitzer, R (2002), “Incidents of police misconduct and public opinion”, Journal of Criminal Justice, 30(5): 397–408.

Tyler, T R (2006), "Why People Obey the Law", Princeton University Press.