Living closer to the resettlement sites of ethnic minorities in Malaysia reduced voter’s preference for ethno-nationalistic politics by improving economic outcomes and enhancing the frequency of casual inter-ethnic contact in shared public spaces.

By 2023, at least 117.31 million people were forcibly displaced (UNHCR 2023). The sudden and rapid inflow of forcibly displaced people has increased support for populist, far right parties (Steinmayr 2021, Dustmann et al. 2019, Halla et al. 2017). Given the vast literature on contact theory (Allport 1954), the impact of inter-group contact on political preferences of the native majority, is central to understanding how policymakers can mitigate the effects of rising anti-immigration and far-right sentiment. What are the long-run economic and political consequences of proximity to out-group members?

In a recent study (Kok and Lim 2024), we answer this using a historical natural experiment: a large-scale, colonial-era, rural-to-rural resettlement programme of ethnic minorities in Malaysia. Between 1949-1952, the programme relocated 500,000 ethnic Chinese from original squatter locations along rivers and jungles to resettlement sites that could be better supervised by the state. We leverage the plausibly exogenous nature of site selection criteria, both with respect to pre-existing economic development and political preferences of receiving communities, to provide the first causal estimates of the long-run impact of persistent differences in transient contact on the economic outcomes and political preferences of the native majority in receiving areas.

Using survey data, we first study micro-level contact, documenting novel evidence that increases in proximity between ethnic Chinese and Malays resulting from resettlement has not led to meaningful increases in inter-ethnic friendships. We do, however, find large increases in sustained casual interactions in shared public spaces. We hypothesise that these casual interactions might have been sufficient for affecting downstream political attitudes (Allport 1954, Enos 2014)

Studying the impact of inter-ethnic proximity on economic and political outcomes in Malaysia

Despite explicit top-down military objectives, the location of Chinese New Villages may be endogenous to unobserved factors. We circumvent this by using a spatial, randomisation inference-style design (Borusyak and Hull 2023, Dell and Olken 2020).

We use plausibly exogenous site selection criteria to construct 1,000 counterfactual village sites for each New Village. We compare the impact of proximity to an actual New Village to the impact of proximity to counterfactual New Villages on surrounding areas (averaged across 1,000 alternative configurations). This yields balance on many predetermined geographic, pre-resettlement demographic and economic variables, providing support that our estimates are unlikely to be contaminated by selection bias or differences in unobservable locational fundamentals.

Political and economic effects of proximity to Malaysian resettlement sites of ethnic minorities

Economic effects

We find a long-run positive economic effect on areas located immediately around resettlement sites (0-2km). Specifically, in a grid-cell analysis, we find that areas located further away from resettlement sites (in increments of 2km bins) have lower nighttime light intensity, population density, and higher agricultural crop productivity.

Figure 1

Strikingly, however, turning to an aggregated, polling district-level analysis, most effects disappear except in immediate 2-4km bins (dip in nightlights and large spike in agricultural crop productivity). These effects are consistent with agglomeration shadows - resettlement led to a spike in population density around resettlement sites that have persisted over time. At the same time, however, resettlement sites appear to have drawn in higher-value economic activities, resulting in more distant areas becoming persistently more agricultural over time (few spillovers) (Hornbeck et al. 2024).

Political effects

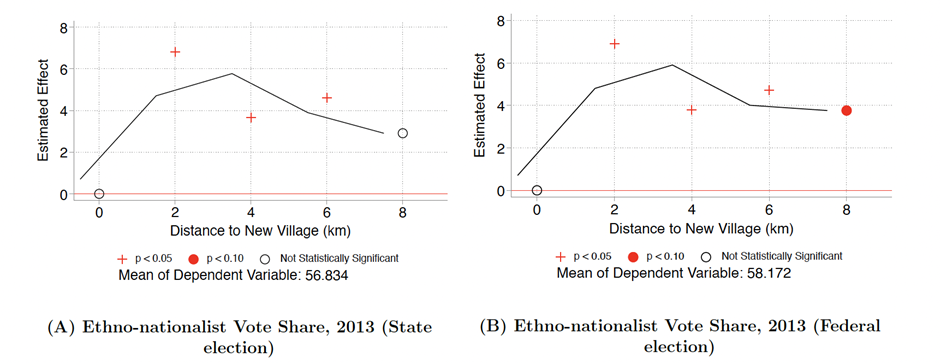

We find that areas in closer proximity to resettlement site had lower vote shares for the ethno-nationalist coalition (2013). Polling districts within 0-2km of the resettlement sites have 3.6 – 6.8 percentage points lower vote shares (mean = 56%) in state and federal elections. We interpret these lower vote shares as representing weaker voter preference for ethno-nationalist policies/politics.

Taken together, we interpret our results as suggesting that ethnic-Malay majority communities that benefitted economically from proximity to resettlement sites were less likely to vote for the ethno-nationalist coalition. One key possibility, in line with the threat hypothesis (Enos 2014), is that the ethnic-Majority no longer saw ethnic Chinese minorities as threats to their economic interest due to their own economic success and hence did not see the need for political power to protect these interests.

Figure 2

Alternative explanations

We rule out two key, potential alternative explanation for lower ethno-nationalist vote shares:

- We find no difference in aggregate voter turnout.

- We show that differences in ethnic composition are insufficient to explain our results - under realistic assumptions that all ethnic-minority voters voted against the ethno-nationalist coalition (Jomo 2017) and an ethnic Chinese voter turn-out rate of 40-50% (consistent with historical voter turnout rates (Malay Mail 2024)

The role of proximity and shared prosperity in reducing ethno-nationalism

Our results have important implications for understanding the conditions under which persistent changes in inter-ethnic proximity can promote positive economic and social change. Given large-scale population displacements from ongoing conflicts and the impending possibility of larger-scale climate disasters, how to best manage inter-group relations remains to be a relevant policy question. In the presence of positive economic outcomes for natives and sustained casual interactions in shared public shapes, the relocation of ethnic groups, even across distinct, segregated communities, can nonetheless spur positive economic and political outcomes.

References

Allport, G W (1954), The Nature of Prejudice, Addison-Wesley, 2: 59–82.

Borusyak, K, and P Hull (2023), “Non-random exposure to exogenous shocks,” Econometrica, 91(6): 2155–2185.

Dell, M, and B A Olken (2020), “The development effects of the extractive colonial economy: The Dutch cultivation system in Java,” The Review of Economic Studies, 87(1): 164–203.

Dustmann, C, K Vasiljeva, and A Piil Damm (2019), “Refugee migration and electoral outcomes,” The Review of Economic Studies, 86(5): 2035–2091.

Enos, R D (2014), “Causal effect of intergroup contact on exclusionary attitudes,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(10): 3699–3704.

Halla, M, A F Wagner, and J Zweimüller (2017), “Immigration and voting for the far right,” Journal of the European Economic Association, 15(6): 1341–1385.

Hornbeck, R, G Michaels, and F Rauch (2024), “Identifying agglomeration shadows: Long-run evidence from ancient ports,” Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Jomo, K (2017), “The new economic policy and interethnic relations in Malaysia,” in Global Minority Rights, pp. 239–266, Routledge.

Kok, C C, and G J Lim (2024), “Ethnic proximity and politics: Evidence from colonial resettlement in Malaysia,” Available at SSRN 5008727.

Malay Mail (2024), “Chinese voter turnout surges to nearly 50pc in Mahkota polls, says DAP’s Chin Tong,” 1 October 2024. Available at: https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2024/10/01/chinese-voter-turnout-surges-to-nearly-50pc-in-mahkota-polls-says-daps-chin-tong/152256.

Steinmayr, A (2021), “Contact versus exposure: Refugee presence and voting for the far right,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 103(2): 310–327.

UNHCR (2023), Global Trends - Forced Displacement in 2023, UNHCR, Geneva.