An unprecedented gender gap in political preferences has emerged in many countries. Evidence from the 2018 Brazilian presidential election shows that labour market shocks which disproportionately affect men can increase support for right-wing populist candidates who embrace traditional masculine values.

The global rise of right-wing populism has sparked renewed interest in its underlying drivers. While previous research has documented how economic shocks can fuel populist attitudes, many studies have focused on grievances surrounding globalisation dynamics—such as rising immigration or import competition—that are particularly salient in high-income countries (Guriev and Papaioannou 2022). However, in low- and middle-income countries, globalisation is often not a central theme, with populists typically emphasising different domestic issues such as crime, corruption, and tensions among social or ethnic groups.

We argue that one common but understudied feature across right-wing populist movements is their approach to gender roles—often characterised by authoritarian, strongman tendencies that combine an exacerbation of masculine stereotypes (aggressiveness, risk tasking, competitiveness, etc.) with ultra-conservative views on women's place in society. We refer to this as a form of supply-side ‘macho politics’. On the demand side, it is now a stylised fact that right-wing populists attract substantially more support from male than female voters, a pattern that has received increasing media attention[1] but whose determinants remain understudied in economics.

In our recent research (Barros and Santos Silva 2025), we investigate how gender-specific exposure to a large economic crisis in Brazil (from 2014 to 17) affected support for Jair Bolsonaro, a far-right politician who embodies macho politics, in the 2018 presidential election.

Brazil’s 2018 presidential election

Brazil's 2018 presidential election presents an ideal case study for understanding the relationship between gender-specific economic shocks and the rise of right-wing populism. First, the election followed a severe economic crisis that disproportionately affected male-dominated industries[2], creating varying labour demand shocks by gender across Brazilian regions. Second, the election winner, Jair Bolsonaro, had a long history of misogynistic comments that brought gender issues to the forefront of the electoral campaign. In fact, shortly before the first round of voting, women organised massive protests against Bolsonaro under the #EleNão (Not Him) movement.

The emergence of an unprecedented gender gap in politics

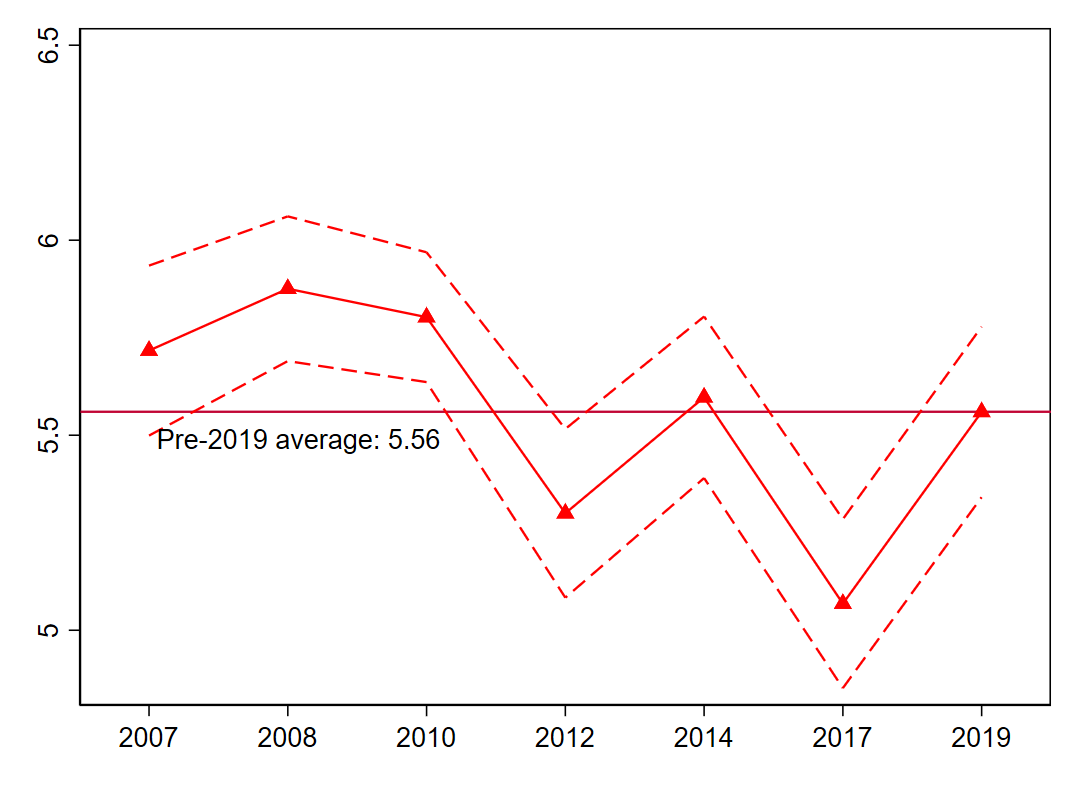

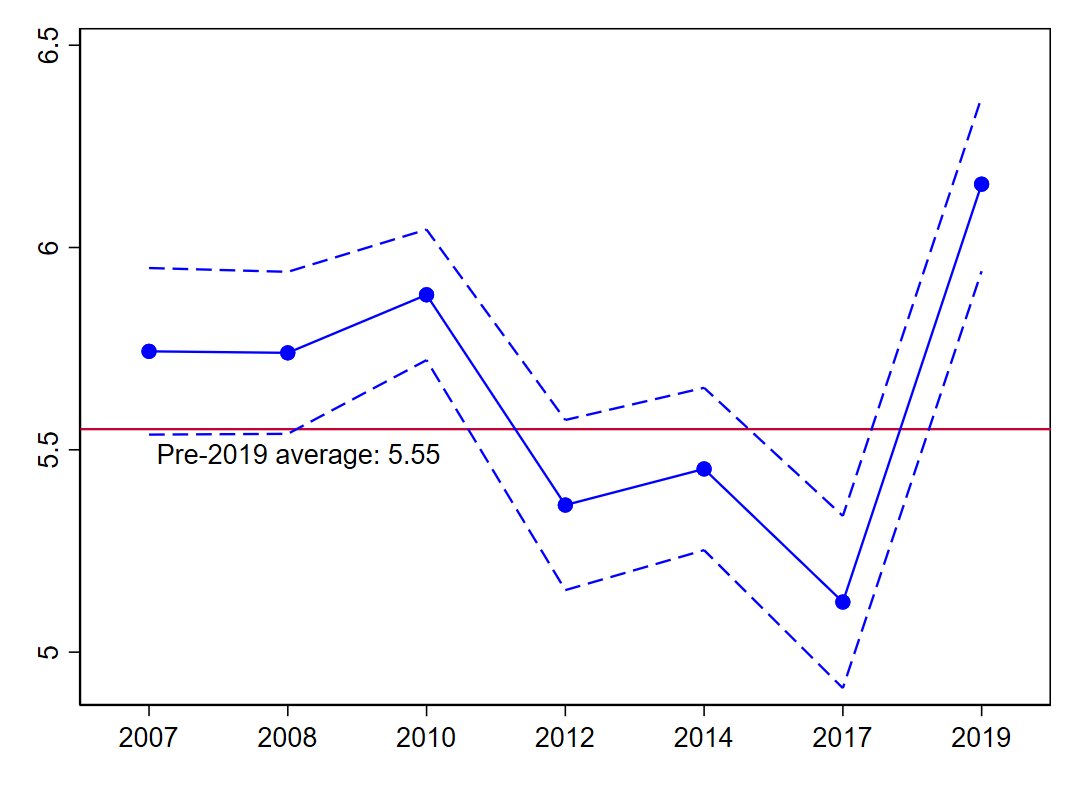

Strikingly, 2018 marked the emergence of an unprecedented gender gap in political preferences in Brazil, as shown in Figure 1. Contrary to Western democracies, where gender gaps in political ideology have been trending for decades (Norris and Inglehart 2000), Brazil previously showed no significant gender differences in political preferences. After 2018, a substantial gap emerged, with men becoming relatively more conservative and more likely to support Bolsonaro.

Figure 1: Self-reported political ideology from 0 (most left-wing) to 10 (most right-wing) by gender

(a) Women (b) Men

Notes: Larger values correspond to moving towards the ideological right. Predicted mean values by gender (conditional on socioeconomic characteristics) with 95% confidence bands. Panel (a) in red colour are women. Panel (b) in blue colour are men. Horizontal red lines plot the average predicted ideology for each gender before 2019 (i.e. pre-Bolsonaro). Before 2019, there is no gender gap in ideology. In 2019, a larger gap emerges, mainly due to men’s rightward shift. Source: Authors’ calculations from AmericasBarometer (LAPOP).

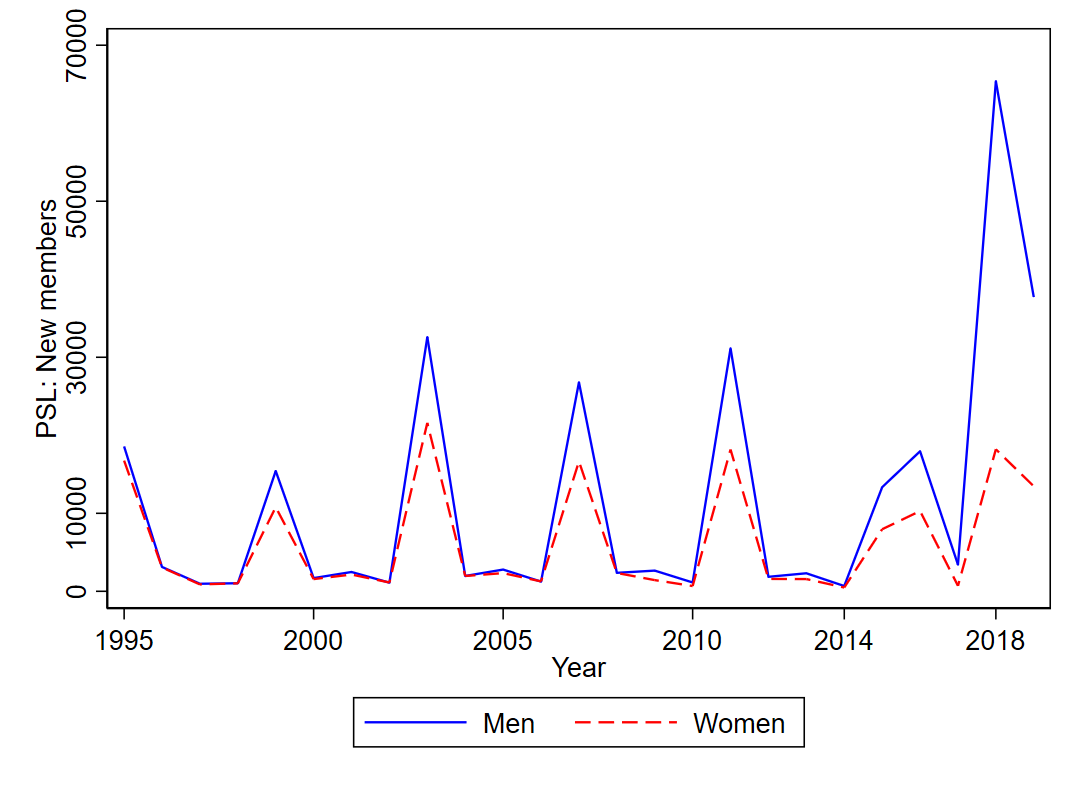

Likewise, as shown in Figure 2, administrative data on party affiliations reveal a dramatic surge in male affiliations for PSL, the party that Bolsonaro joined ten months before the 2018 election. Female affiliations, on the other hand, evolved similarly to previous election cycles.

Figure 2: Yearly number of new PSL members by gender, 1995-2019

Notes: Bolsonaro joined the party in January 2018, only ten months before the October elections. The party was founded in late 1994. Source: Authors’ calculations from TSE data on party affiliations.

Measuring gender-specific economic shocks across regions

Our research examines how local employment losses by gender across regions in 2014-17 affected votes in the 2018 presidential election. Using a so-called shift-share approach (Bartik 1991, Borusyak et al. 2022), we create gender-specific measures of exposure to the economic shock at the regional level.

For each region, we calculated a weighted average of the pre-crisis regional employment shares (separately for men and women) across detailed industry codes and the national change in employment during the 2014-17 recession by gender for each industry. This approach leverages variation in three key factors: (1) different industries have different employment responses to business cycles, (2) they employ men and women at different rates, and (3) they are spread unevenly across regions.

To illustrate, imagine one region specialising in construction—a male-dominated industry that is highly cyclical—versus another region specialising in domestic services—a female-dominated industry with much less cyclicality. These regions would experience very different gender patterns in job losses during an economic crisis, with men in the former region expected to be much more severely affected than in the latter.

Gender-specific shocks influence voting behaviour in Brazil

Our findings reveal a striking pattern: in regions where men experienced larger economic shocks relative to women, support for Bolsonaro was significantly higher. Conversely, in areas where women were disproportionately affected by the recession, his vote share was lower. We find opposite effects for the left-wing Workers' Party (PT), whose vote share declined more relative to the 2014 election in regions with larger male-specific shocks.

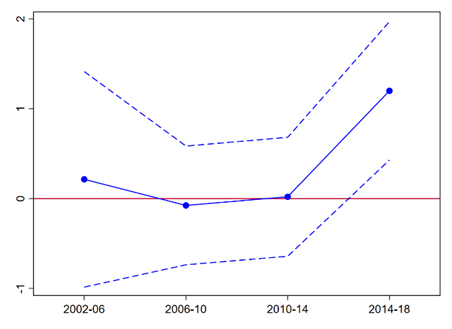

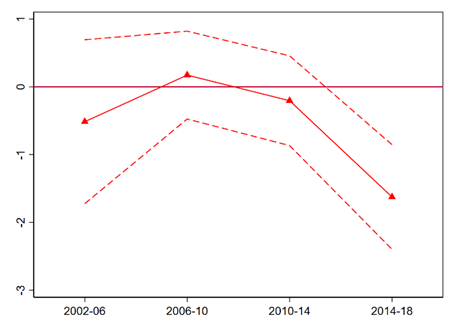

Importantly, Figure 3 shows that our finding is unique to the 2018 election. The figure plots the coefficients of employment growth by gender for each 4-year election cycle between 2002 and 2018 on votes for PT, the left-wing party of the incumbent presidents (Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff) in the period. Before the crisis cycle, we find no relationship between gender-specific shocks and voting outcomes. This finding supports our view that the supply of populist rhetoric by Bolsonaro interacted with the gendered demand for such rhetoric created during the crisis. In previous elections, when these two ingredients are absent, the relationship disappears.

Figure 3: Estimated effect of an increase in employment on the change in votes for PT by four-year presidential election cycle by gender, 2002-2018

(a) Effect of male employment growth (b) Effect of female employment growth

Notes: The figure shows estimated effects for male employment changes in blue (Panel (a)) and for female employment changes in red (Panel (b)). Dashed lines are 95% confidence intervals. Before the 2014-18 cycle, the gender-specific employment shocks have a very small and statistical insignificant effect on voting outcomes. In the 2014-18 cycle, there are large and opposing effects. Increases in male employment raise the vote share of leftwing PT (i.e. conversely, male employment losses raise Bolsonaro’s vote share). Female employment has the opposite effect.

How do gender stereotypes reinforce voting behaviour?

What explains this gender divergence in response to economic hardship? We hypothesise that when men experience shocks to their breadwinner identity, they are more likely to embrace a candidate who emphasises masculine stereotypes as a way of compensating for perceived losses in social and economic status.

Previous research has shown that employment and earnings are central to male identity (Bertrand et al. 2015, Autor et al. 2019), and, when these are threatened, men often respond by exaggerating their masculinity and aggressiveness (Cheryan et al. 2015). In political science, the ‘fragile masculinity hypothesis’ suggests that insecurities around men's gender identities drive populist and authoritarian tendencies (DiMuccio and Knowles 2020).

Our analysis of World Values Survey data supports this interpretation. We found a significant gender gap in support for abortion (a highly polarising issue in Brazil, where it is illegal) emerging in 2018 among economically dissatisfied respondents, with men becoming relatively more conservative. No such gap exists among economically satisfied respondents, nor did it exist in previous years or in Mexico (which we use as a placebo country).

Implications of gender and populism on politics

Our findings suggest that policymakers and political analysts should pay closer attention to how economic shocks affect different demographic groups, as these differential impacts can have profound electoral consequences. Understanding how economic vulnerability interacts with social identity—particularly gender identity—may contribute to reducing the appeal of populist movements worldwide.

Bolsonaro was eventually voted out of office in 2022. On account of multiple electoral and criminal cases, he is currently barred from holding political office and under trial for promoting a failed coup after his electoral defeat. However, it remains to be seen whether the profound gender cleavages we document will outlast him.

References

Autor, D, D Dorn, and G Hanson (2019), “When work disappears: Manufacturing decline and the falling marriage-market value of young men,” American Economic Review: Insights, 1(2): 161–178.

Barros, L, and M Santos Silva (2025), “Economic shocks, gender, and populism: Evidence from Brazil,” Journal of Development Economics, 174: 103412.

Bartik, T J (1991), "Who Benefits from State and Local Economic Development Policies?" WE Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

Bertrand, M, E Kamenica, and J Pan (2015), “Gender identity and relative income within households,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(2): 571–614.

Borusyak, K, P Hull, and X Jaravel (2022), “Quasi-experimental shift-share research designs,” Review of Economic Studies, 89(1): 181–213.

Burn-Murdoch, J (2024), “A new global gender divide is emerging,” Financial Times.

Cheryan, S, J S Cameron, Z Katagiri, and B Monin (2015), “Manning up,” Social Psychology, 46(4).

DiMuccio, S H, and E L Knowles (2020), “The political significance of fragile masculinity,” Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 34: 25–28.

Guriev, S, and E Papaioannou (2022), “The political economy of populism,” Journal of Economic Literature, 60(3): 753–832.

Klein, E (2024), “Manliness, cat ladies, fertility panic and the 2024 election,” The New York Times.

Norris, P, and R Inglehart (2000), “The developmental theory of the gender gap: Women’s and men’s voting behavior in global perspective,” International Political Science Review, 21: 441–463.