Migration can act as a powerful tool for upward mobility. Evidence from Indonesia indicates that the benefits of migration depend on a household's initial education level, the age at which a child migrates, and the origin and destination locations.

Millions of families migrate each year in search of better opportunities, but not all children benefit equally from such moves. Extensive research underscores the potential benefits of migration for adults, especially in developing countries, where moving to urban centres or economically dynamic regions often improves incomes and livelihoods (Bryan et al. 2014, Hamory et al. 2020). However, the implications for children are more complex. Studies suggest that access to better schools, safer neighbourhoods, and more educated peer groups can be transformative (Chetty et al. 2016, Van Maarseveen 2022). Yet, in many developing contexts, most migration remains rural-to-rural, where such advantages may be limited. In Indonesia, with its stark regional disparities in education, my study examines how destination quality shapes children’s educational outcomes (Schwank 2024).

Internal migration in Indonesia

Indonesia has a long history of internal migration. Since colonial times, the government’s “Transmission Program” has facilitated the movement of landless households to sparsely populated islands. Non-government-organised internal migration has also played a significant role. According to the 2000 Population Census, 5.9% of the population aged five or older reported migrating across district borders within the past five years. These moves, while primarily motivated by economic or social factors, also expose children to vastly different educational environments. As Suharti (2013) documents, there is substantial variation both across and within provinces in terms of average years of schooling, as well as in the qualification of teachers. Hence, the destination may play a critical role in shaping children’s educational outcomes.

The impact of internal migration in Indonesia on education outcomes

In estimating the effect of internal migration on educational attainment, several issues arise:

- The effect of destination may depend on the duration of an individual’s stay.

- Families may vary in their willingness or ability to invest in children’s education, leading to biased estimates.

- Difficulties in comparing destination quality with place of origin.

I address each of these empirical challenges by using the seminal age-at-migration approach developed by Chetty and Hendren (2018). This methodology can be used to identify how the length of exposure to the destination impacts a migrant child’s outcomes. Additionally, I define destination quality as the difference in educational attainment between the permanent residents of destination districts and origin districts. By constructing this variable separately for each birth cohort, district quality is captured at specific points in time.

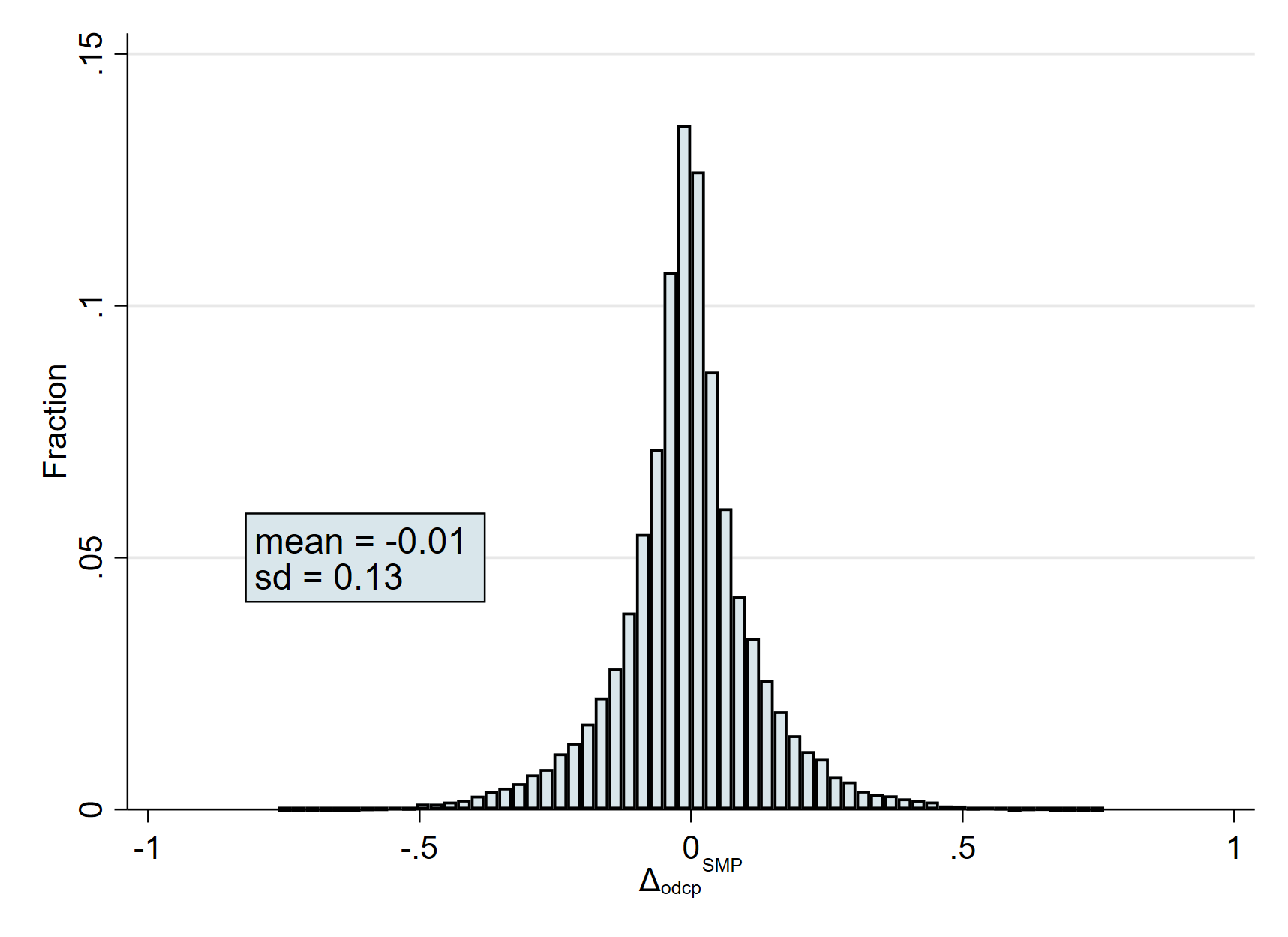

Figure 1 plots a histogram of this district quality change measure, revealing that migration flows both ways, and about half of the children migrated to a district with higher quality, while the other half migrated to a district with lower quality.

Figure 1: Histogram of the change in district quality using sample of 15–20 year olds

Notes: The figure shows the change in junior secondary school graduation rates between destination and origin districts for migrants aged 15–20, based on 2000 and 2010 Indonesian Census data. Rates are calculated by birth cohort and parental education group. Sample: one-time migrants aged 15 to 20 from 2000 and 2010 Indonesian Population Census.

I introduce a novel approach to infer migration timing in data-sparse contexts, leveraging differences in siblings’ birth years and locations within Indonesia’s Population Census data (2000 and 2010). This methodology is particularly valuable for studying migration in developing countries, where detailed longitudinal data is often unavailable.

Children gain more when they migrate at younger ages

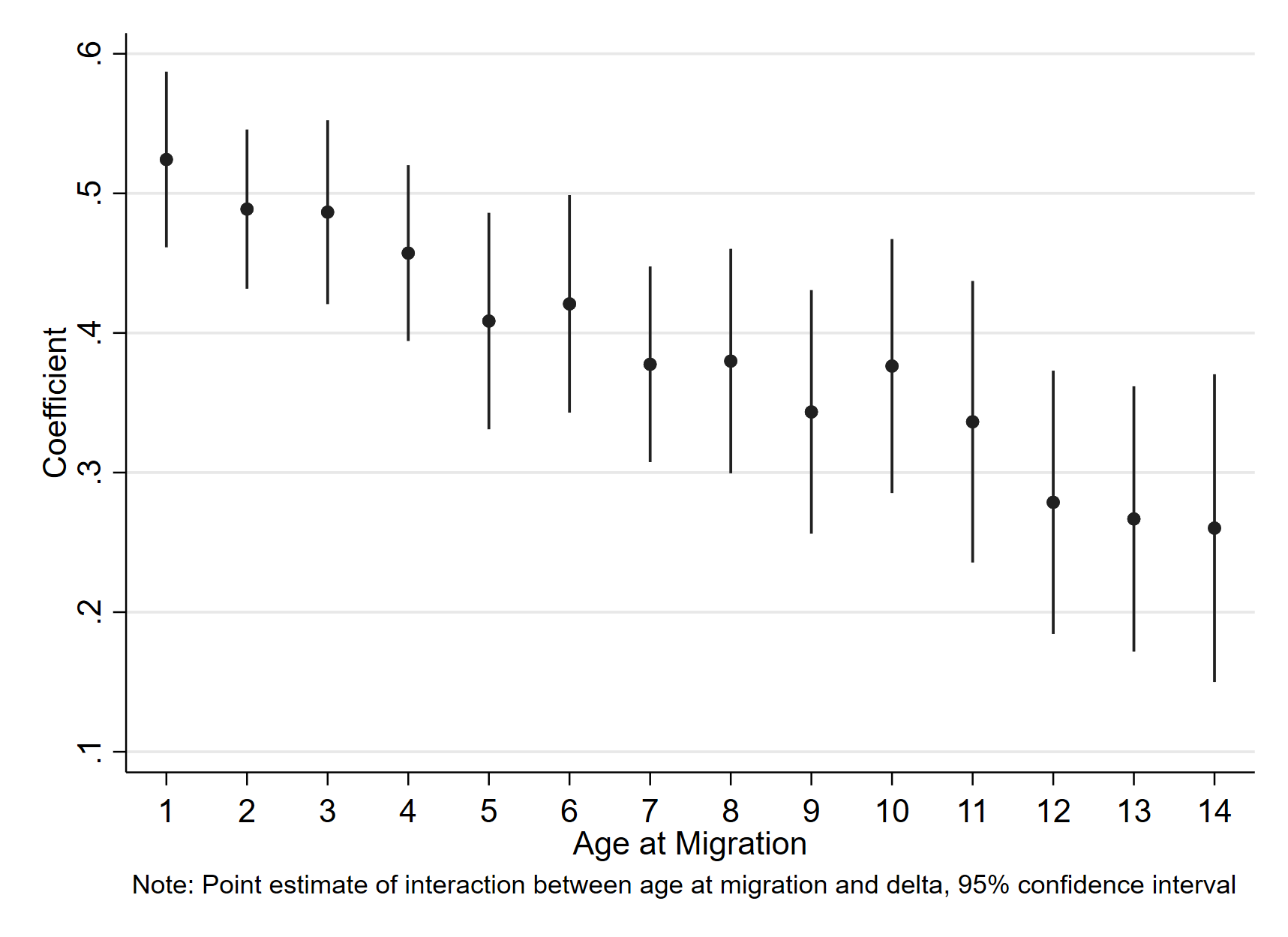

Children who move earlier to districts with higher educational attainment among permanent residents are significantly more likely to complete primary and secondary education. This can be seen in Figure 2a which plots the relationship of the likelihood of completing junior secondary school and the change in district quality at different ages at migration. The idea behind it is simple: the earlier a child moves to a district with better education opportunities, the longer they can benefit from those advantages.If parents with a greater propensity to invest in their children’s education choose higher quality destinations, each of these coefficients may be subject to upward bias. However, this selectivity is unlikely to depend on the child's age at migration. I can hence calculate the differences in coefficients across ages at migration to derive a causal estimate of the yearly destination effect for a migrant child. By observing how these coefficients change with age at migration, I assess how the length of exposure affects junior secondary school completion.

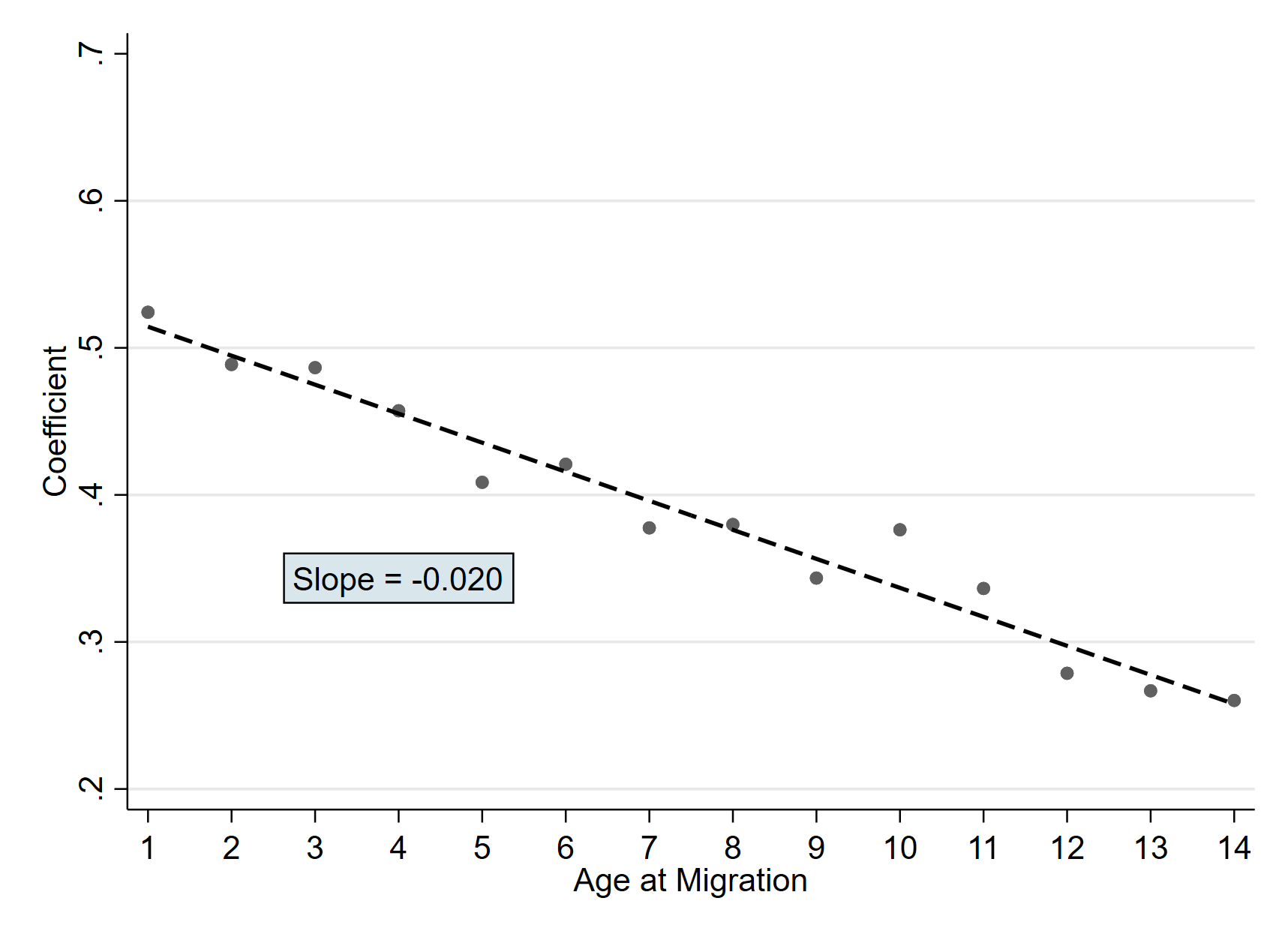

Figure 2a reveals a clear downward pattern of the coefficients. This suggests that children who migrate at a younger age gain more than those who migrate later, as they have more exposure to the new environment. Figure 2b presents a linear fit of this relationship. The slope of -0.02 implies that during each year of exposure, educational outcomes of migrant children converge to outcomes of the locals at a rate of 2%. For every additional year a migrant child spends in a one standard deviation better destination, the likelihood of graduating from junior secondary school increases by 0.26 percentage points per year.

Figure 2: Location exposure effect on junior secondary school graduation (Age 15–20).

Notes: Figure 2a shows the effect of location quality change on junior secondary school graduation by age at migration during childhood, with 95% confidence intervals and clustered standard errors. Figure 2b presents the linear fit of these effects, representing the location exposure effect. Sample: one-time migrants aged 15–20 from 2000 and 2010 Indonesian Censuses; maximum migration age is 14 years.

I observe similar effects on the completion of primary school and senior secondary school. Each additional year a child spends in a destination that is one standard deviation higher in quality increases their likelihood of completing primary school by 0.17 percentage points and senior secondary school by 0.22 percentage points. Interestingly, migration affects children’s educational outcomes symmetrically: moving to better-quality destinations leads to improvements, while relocating to worse areas results in comparable declines.

Children from less educated households benefit more from exposure to better districts

Crucially, the benefits are not evenly distributed across all groups. Children from less educated families gain the most from moving to higher-quality destinations, with each additional year in a better district increasing their likelihood of junior secondary school completion by 0.34 percentage points—a significant boost compared to children of more educated parents. This suggests that migration serves as a mechanism for upward mobility, helping to close the intergenerational education gap for disadvantaged families.

Gender also plays a role. Girls tend to benefit slightly more than boys from exposure to better destinations, reflecting differences in how gender influences educational opportunities and outcomes. However, these effects vary less dramatically compared to differences across socioeconomic groups, signalling that destination quality is a key equaliser in bridging broader educational disparities.

Reducing barriers to internal migration and offering information on migration choices can improve children’s educational outcomes

These findings highlight the important role of internal migration in shaping children’s educational outcomes. They suggest that policies aimed at reducing barriers to internal migration can facilitate opportunities for families and promote human capital development. However, outcomes vary by destination quality, which may be a difficult measure to assess for families. Offering information to households considering migration could hence enhance their decision-making process and subsequently improve children’s outcomes. Moreover, education quality within rural areas should be an important priority for policymakers, as such regions constitute a significant portion of migrant destinations in developing countries.

Further investigation is needed to better understand the key factors that define a “high-quality” district. By exploring determinants such as school and peer quality, local perceptions of educational returns, economic conditions, and cultural and religious norms, we can gain a deeper understanding into how destination characteristics influence child outcomes.

References

Bryan, G, S Chowdhury, and A M Mobarak (2014), “Underinvestment in a profitable technology: The case of seasonal migration in Bangladesh,” Econometrica, 82(5): 1671–1748.

Chetty, R, N Hendren, and L F Katz (2016), “The effects of exposure to better neighborhoods on children: New evidence from the moving to opportunity experiment,” American Economic Review, 106(4): 855–902.

Chetty, R, and N Hendren (2018), “The impacts of neighborhoods on intergenerational mobility I: Childhood exposure effects,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133(3): 1107–1162.

Hamory, J, M Kleemans, N Y Li, and E Miguel (2021), “Reevaluating agricultural productivity gaps with longitudinal microdata,” Journal of the European Economic Association, 19(3): 1522–1555.

Suharti, S (2013), “Trends in education in Indonesia,” in Education in Indonesia, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS).

Van Maarseveen, R (2022), “The effect of urban migration on educational attainment: Evidence from Africa,” PAA 2022 Annual Meeting.

Schwank, H (2024), “Childhood migration and educational attainment: Evidence from Indonesia,” Journal of Development Economics, 171: 103338.