Government-led construction of manufacturing plants in dispersed US locations during WWII led to persistent increases in local manufacturing employment and wages, and increased upward economic mobility among pre-war residents who benefitted from local access to higher-wage work.

Even in most advanced economies, many subregions are left behind by economic growth. It is well-documented that the disappearance of high-wage manufacturing work from regions due to trade competition and technological change has had dire impacts on residents, many of whom remain in impacted regions (Wilson 1997, Moretti 2013, Autor et al. 2016, Charles et al. 2019). Many policymakers and academics alike now hope that policies that boost local production employment in afflicted regions might in turn increase employment rates and incomes of the left-behind local population (Austin et al. 2018, Bartik 2020, Slattery and Zidar 2020). However, while there is abundant evidence about what happens when work disappears from a region, we know rather little about what happens when new work appears. Do new work opportunities improve career outcomes for initial residents? Or are new jobs largely filled by outsiders or perhaps they simply replace similar existing jobs in the region?

To obtain evidence about these questions, we looked back at one of the largest government economic interventions in US history: the industrial mobilisation for World War II (WWII). More specifically, our recent research (Garin and Rothbaum 2025) studies the long-run effects of government-led construction of manufacturing plants for war production on regions and the specific people from those regions.

Government-led plant construction during WWII

The industrial mobilisation for WWII was the largest government-driven economic expansion in United States history. As war broke out in Europe in 1939, the United States government began a massive programme of industrial expansion to produce necessary quantities of key war products, a programme which expanded dramatically in scale and urgency after the US entered WWII at the end of 1941. Throughout the war effort, the US military relied on private firms for the overwhelming majority of production. However, firms were reluctant to be on the hook for the new, large-scale plants around the country the military viewed as necessary to achieve both a sufficient scale of production and a secure supply chain.

In response, the US government directly financed the construction of strategic industrial plants in dispersed locations across the country with little history of production in target industries. Siting decisions for these plants were made by military officials motivated by a combination of strategic considerations and short-run expediency. The new plants were run by executives from leading firms and were staffed by local workers, most of whom had no prior related experience and were trained on-site. Most government-financed plants continued to operate after the war.

In our study, we focus on the construction of large, publicly financed plants costing over $10 million ($200 million in 2024 dollars) built in dispersed locations outside of preexisting major industrial centers. While these large plants needed to be sited near sufficient basic resources and population, location decisions were otherwise driven primarily by idiosyncratic considerations that would not have otherwise been relevant outside the context of the war emergency. Therefore, we estimate causal effects of plant construction by comparing counties where plants were built to other similarly populated counties outside of major manufacturing centers - an approach supported by the absence of any association between “treatment'' status and county characteristics in any year prior to the war among counties with comparable populations.

Persistent impacts of plant construction on regional economies in the US

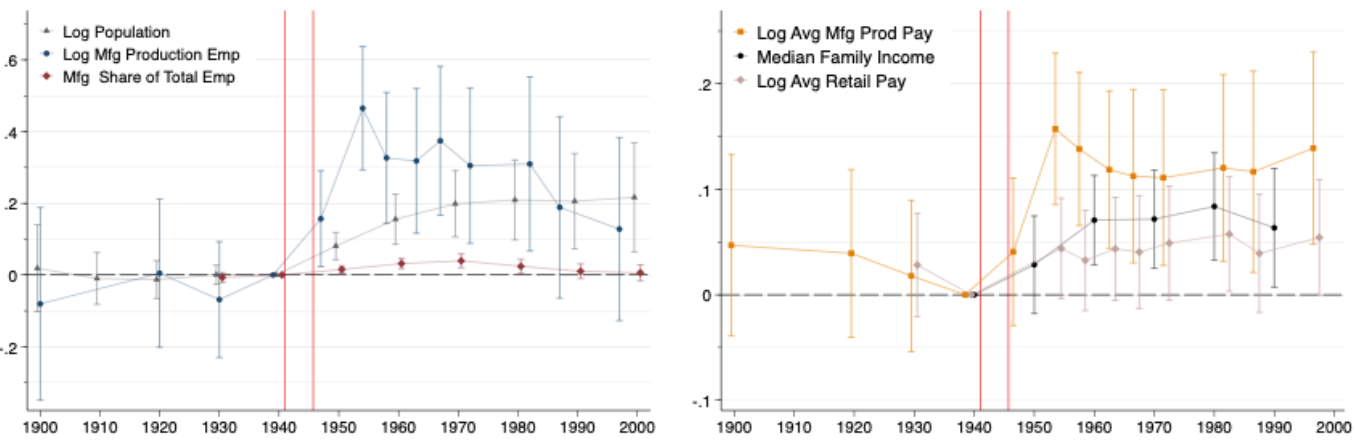

Plant construction had large and persistent impacts on regional development. Figure 1 Panel A shows that, in the immediate aftermath of the war, manufacturing employment in treatment regions expanded by roughly 30% in comparison to control regions. In the short run, local population growth through migration occurred gradually, manufacturing employment increased as a share of total employment by two percentage points. In the longer term, population in treated counties continued to grow, stabilising at a new, permanently higher level about 20% above that of control regions, with manufacturing no longer representing an outsized share of employment.

Figure 1: Impacts of WWII plants on county development

(a) Effects on county population & employment (b) Effects on avg wages & median earnings

Notes: This figure shows estimated impacts of wartime plant construction in a county on county-level outcomes over time and associated 95% confidence intervals. All outcomes are differences relative to 1940 outcome levels (or 1939 as available) to compare differential increases in outcomes, 1940 effects are zero by construction. Each estimate and the associated 95% confidence interval is from a separate regression of the differenced outcome measured in the year specified in the x-axis on the treatment indicator. Estimates are drawn from Garin and Rothbaum (2025).

We find that wartime plant construction also led to a permanent 10% increase in the average manufacturing production worker wage, as is evident in Figure 1 Panel B. Notably, there was not a comparable increase in average wages in other sectors, for instance, the effect on retail wages was less than half the magnitude of the increase in manufacturing wages and not statistically different than zero in most years. Nonetheless, the large increase in manufacturing wages during a period of expanding manufacturing employment drove an increase in median family earnings by 7-8% during the postwar decades. In additional analyses, we find that this increase in median family earnings was driven primarily by higher male earnings and more specifically, higher wages within semi-skilled blue-collar occupations.

Impacts on careers of prewar residents from wartime plant construction in the US

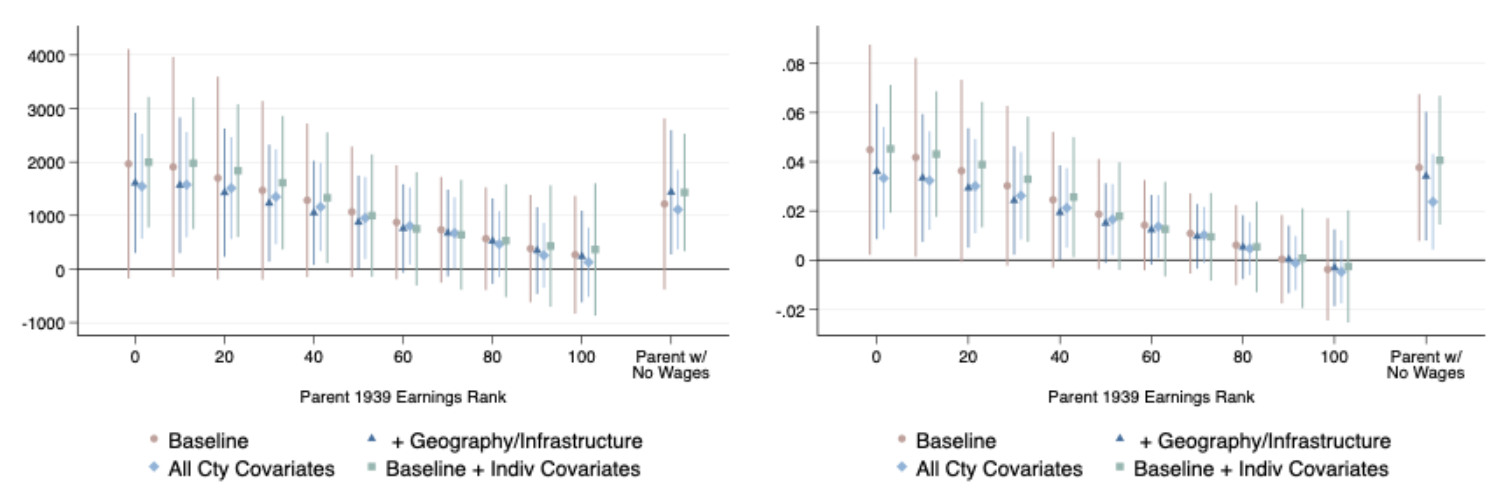

To assess whether wartime plant construction benefitted the population living in affected regions before the war, we compare post-war outcomes of individuals who were born between 1922-1940 in either treatment or comparison counties, as observed in Social Security records. We estimate that, on average, men born in treatment counties in the 18 years before the war had $1,200 (2020 dollars) more in annual wage earnings than those born in comparison counties. Figure 2 shows that these effects were largest for male children of the parents with the lowest prewar earnings, for whom plant construction increased adult earnings by $1,800 per year in adulthood, approximately a 3-4% increase, and that there were no effects for children of parents with the highest prewar earnings. We find that while plants increased women’s household earnings, there were no effects on the individual earnings of women. However, wartime production led to a decline in earning gaps between black and white men, particularly among black and white children of higher-earning parents.

Figure 2: Long run earning effects on men born before WWII in counties where war plants were built

(a) Effects on earnings in 2020 dollars (b) Effects on earnings (in logs)

Notes: This figure shows estimated impacts of wartime plant construction on adult earnings of individuals born in affected regions between 1922–1940 and associated 95% confidence intervals. The outcome is 1969–1984 average wage earnings reported on IRS 1040 returns. We run separate regressions for children with parents with 1939 earnings ranks in different ranges centered around the value displayed on the x-axis; each estimate is from a separate regression. Estimates are drawn from Garin and Rothbaum (2025).

Why did men from low-income backgrounds benefit from war plant construction? Several pieces of evidence suggest that they benefitted primarily from increased access to higher-wage jobs in adulthood. We find the effects on adult earnings are entirely accounted for by location in adulthood and are driven by those who remain in their birth county. We also document that treated individuals were themselves more likely to work in industries paying higher wage premiums as adults. Meanwhile, the accumulation of general human capital appears to play a smaller role. While plants led to modest increases in educational attainment for children of the lowest-earning parents, the effects are not large enough to account for the observed increase in earnings in adulthood.

Implications for contemporary place-based policy

Our findings highlight the potential for place-based economic policies to expand opportunities for economic advancement among residents of target regions. Yet our analysis also gives reason to think that the success of any proposed place-based intervention will depend crucially on the details. Policymakers aiming to promote upward mobility should carefully consider whether an intervention will generate paths to higher-wage employment for the people already living in a target area. Those goals may not align with other objectives of industrial policy such as the reshoring of strategic sectors or the development of nascent industry clusters that might contribute to productivity growth. WWII plant construction may have been particularly effective at improving outcomes for local residents in part because officials were acting to meet the needs of a short-term defense crisis and not pursuing longer-term economic efficiency. In order for new plants in peripheral regions to quickly reach output goals for new products, every available worker in the community had to be put to work as effectively as possible, fueling employment in semi-skilled occupations that offered better pay for workers with less formal education. A key question for future research is whether the types of incentives used by contemporary policymakers to attract jobs to distressed regions can in practice replicate the impacts we find in the case of a war-driven industrial expansion.

References

Austin B, E Glaeser, and L Summers (2018), "Jobs for the heartland: Place-based policies in 21st-century America," Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 49(1 (Spring)): 151–255.

Autor D H, D Dorn, and G Hanson (2016), "The China shock: Learning from labor-market adjustment to large changes in trade," Annual Review of Economics 8: 205–240.

Bartik T J (2020), "Using place-based jobs policies to help distressed communities," Journal of Economic Perspectives 34(3): 99–127.

Charles K K, E Hurst, and M Schwartz (2019), "The transformation of manufacturing and the decline in US employment," NBER Macroeconomics Annual 33(1): 307–372.

Moretti E (2013), The new geography of jobs. Boston, Mass: Mariner Books.

Slattery C and O Zidar (2020), "Evaluating state and local business incentives," Journal of Economic Perspectives 34(2): 90–118.

Wilson W J (1997), When work disappears: The world of the new urban poor. New York, NY: Vintage.