Fertility and childcare

Ever since the theoretical foundations of the economics of the family were developed (Becker 1965, Becker 1981), economists have recognised that women’s home production and participation in the paid labour force may interact due to many factors, including the allocation of time towards childcare responsibilities. However, empirically testing the relationship between childcare and fertility is frequently confounded by the many other factors that affect fertility decisions such as education and access to contraception. Empirical tests also face a “reverse causality” issue, since higher labour force participation may impact the decision to bear children or to use contraception. Research summarised in this section has therefore used a variety of strategies to estimate plausibly causal effects of fertility and childcare on female labour force participation. Overall, there is both consistently positive evidence of the effect of improved childcare and substantial heterogeneity in the effects of fertility availability on labour force participation by country, highlighting the importance of context-specific factors like job availability, overall labour market structure, and social support structures for working families.

Fertility

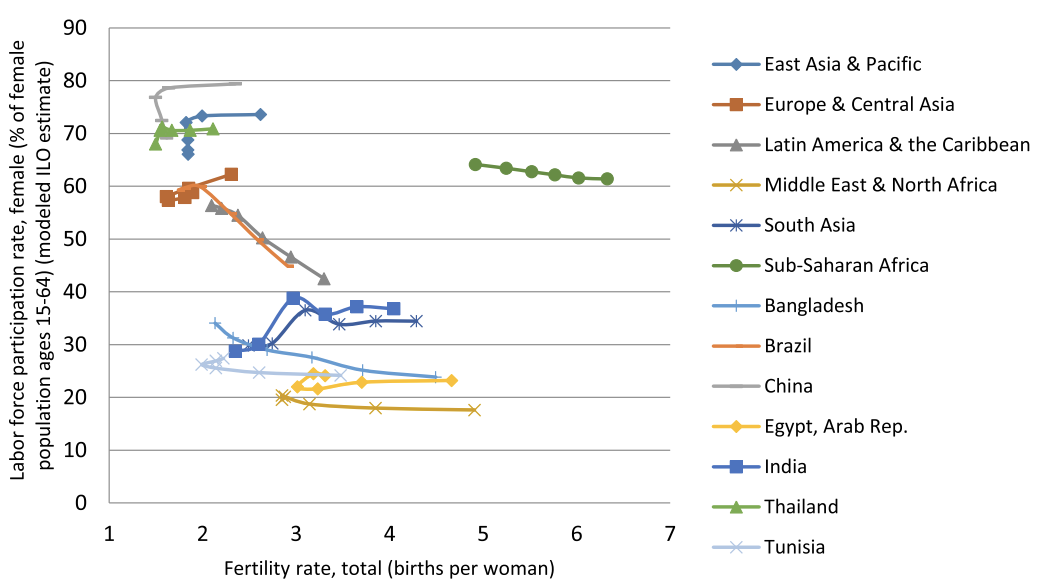

Evidence at a macro-level is mixed on the impact of fertility on female labour force participation. While overall fertility levels worldwide have been falling, there has not been a corresponding worldwide increase in female labour force participation rates. As Klasen (2019) notes, the overall correlation is generally flat; see Figure 2.

Figure 2: Total Fertility Rate and Female Labour Force Participation Rate (15-64) by region and selected countries

This finding departs strongly from the work of Bloom et al. (2009) that suggested there is a strong, negative relationship between fertility and female labour force participation. One notable difference between the two studies is the choice of sample; Bloom et al. (2009) include richer countries, for example. Hausmann and Székely (2001) find in their analysis of 15 Latin American countries that the effect of fertility on labour force participation is highly heterogeneous. Thus, the evidence suggests that any relationship between fertility and labour force participation is context specific. Indeed, Aaronson et al. (2021) study 103 countries from 1787-2015 and find that the effect of fertility on labour supply depends upon the level of economic development as well as the structure and types of jobs available to women.

Empirical microeconomic studies based in low-income settings tend to find stronger effects of fertility (or, contraception access, more precisely) on female labour force participation. These results are echoed in a narrative review by Finlay (2021) demonstrating that there are linkages between reproductive autonomy, childbearing, and labour force participation on the extensive and intensive margin. Canning and Schultz (2012) review the evidence from micro-level studies and similarly find that access to contraception increases female labour force participation. Both Herrera Almanza and Sahn (2018) in Madagascar, as well as Miller (2010) in Colombia, find that large family planning programmes increased labour force participation in the formal sector. Both of these papers highlight that postponing a woman’s first birth in particular may be an important indicator of when and whether women enter paid employment. Other work by Herrera Almanza et al. (2019) in Madagascar suggests that because contraception affects the timing of the first birth, it also affects the timing of labour force entry (via school disenrollment) and may also affect the type of employment women pursue. More recent evidence similarly finds that a randomised female empowerment programme for adolescents, including information on sex and contraception, resulted in lower rates of childbearing and higher rates of self-employment in Uganda (Bandiera et al. 2020). On the other hand, Branson and Byker (2018) find that the effect of an intervention aimed at reducing childbearing in South Africa had no impact on employment despite finding increases in wages. Thus, the microeconomic evidence confirms that the impact of fertility on women’s labour market outcomes is very likely context-specific.

Childcare

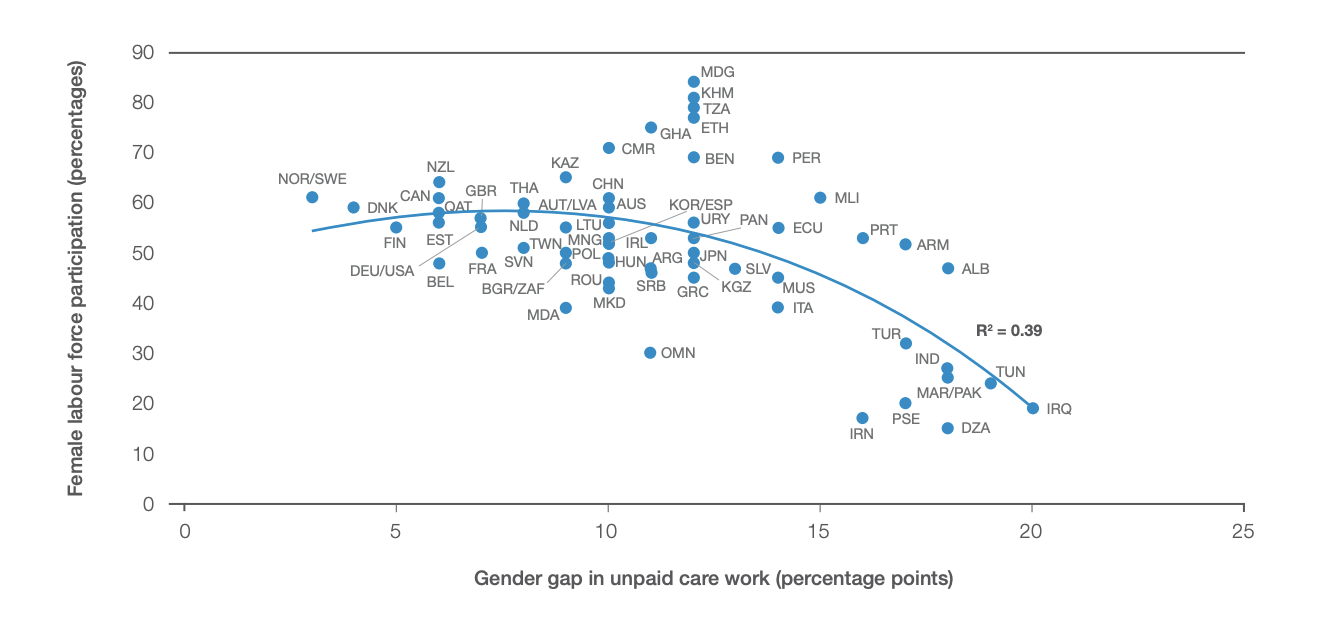

Worldwide, women typically do the bulk of unpaid care work, potentially making it relatively more difficult for them to also engage in paid employment. A report by the International Labor Organization on the state of unpaid work and labour markets supports this hypothesis (Addati et al. 2018). This report cites data showing that women are substantially more likely than men to report child and home responsibilities as reasons for not engaging in paid labour. Similarly, in countries where women do relatively more of the unpaid childcare work (compared to their male counterparts), women’s labour force participation is lower, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Relationship between the gender gap in unpaid care work and women’s labour force participation in 2017

Globally, high-quality childcare is expensive, leading older children and other relatives to frequently contribute to childcare duties. Talamos-Marcos (2023) documents that in Mexico, for example, the death of a grandmother in the household reduces maternal labour supply by 12 percentage points since mothers disproportionately assume childcare responsibilities. Simply leaving children unattended may also be a typical strategy used when others are unavailable. One estimate indicates that over 35.5 million children under five are left without any adult supervision (Samman et al. 2016).

Given the lack of childcare options, women typically work shorter hours and as many as 38% of women bring their children to work with them, a pattern correlated with lower earnings and profits for self-employed women as compared to men (Delecourt and Fitzpatrick 2021). Seeking flexibility to combine work and childcare, there is evidence that women working with children tend to adjust their work location and the type of industry they join (Delecourt et al. 2023) and switch from wage to self-employment (Heath 2017, Berniell et al. 2021). This correlation suggests that across the world, women’s labour force decisions are at least partly based upon childcare needs, and that for many families there is a porous boundary between work and home life (Bertrand et al. 2010, Le Barbanchon et al. 2021).

Given evidence on the effect of children on women’s careers, research has examined the effects of childcare on women’s career outcomes. In their meta-analysis, Halim et al. (2023) find that in 21 out of 22 studies from low-income countries, improved access to childcare increased female labour force participation on both the extensive margin (whether a woman works at all) and intensive margin (how many hours a woman works). Work not included in that study has demonstrated similar findings.[1] For example, Clark et al. (2019) in Kenya find that a one-year voucher for private childcare increased employment by 10 percentage points despite only having a 30% take-up rate. They also document that due to the more regular childcare arrangements that the voucher facilitated, women changed their types of employment from flexible jobs such as sales and laundry to those with more regular hours in the service sector. Hojman and Lopez Boo (2022) find that mothers induced to utilise a public childcare programme in Nicaragua by its random assignment to their neighborhood were 12 percentage points more likely to work. Martinez and Perticara (2017) show that childcare provided to older children can also increase female labour supply; they find that offering after-school care for children aged 6-13 increases maternal employment by 4.3 percentage points.

Two exceptions run counter to the finding that childcare raises female labour supply. Bjorvatn et al. (2022) randomised Ugandan households into either a childcare voucher; a cash grant of equivalent value; both, or neither. They find significant increases in maternal work only in the cash grant treatment arms. While the childcare only arm increased the likelihood of working outside the home only for fathers, it did increase the business earnings of mothers. A randomised programme that provided access to free daycares in Brazil found that there were no differences in female labour force participation once children reached school-age, suggesting that other household production constraints may affect labour force participation even when childcare is available (Reimão et al. 2023).

There is an exciting, and growing, body of work examining whether community-organised nurseries, daycares, and preschools impacts parental outcomes. Donald et al. (2023) find that community-based childcare centres in the DRC are heavily used, resulting in increases to women’s agricultural productivity and also a 2.4 percentage point increase in women’s likelihood of engaging in non-agricultural wage work. Ajayi et al. (2022) similarly find that the facilitation of community-based childcare facilities at public works projects in Burkina Faso increased female employment by 8.3 percentage points. Together, these studies suggest that women do demand childcare, and community organised childcare facilities are a promising method to meet this demand and improve women’s labour market outcomes.

Intra-household constraints

Women’s labour supply decisions are rarely made by women alone; typically other family members are also involved. The decisions will therefore depend not only on women’s preferences but also on the preferences of other family members and the process by which the family makes decisions. The literature typically focuses on the dynamic between husbands and wives as working-age women are very often married, though some research allows for the role of other family members like the women’s parents or parents-in-law.

In standard models, labour is a disutility so greater control in the household should allow women to work less. There is indeed evidence of this hypothesis in developed countries (Angrist 2002, Chiappori et al. 2002, Rangel 2006). However, new data from developing countries suggest this basic premise may not apply there.

Bursztyn et al. (2023) present nationally representative statistics from 60 countries on norms about women’s employment. They find that in virtually every country, women are more likely than men to agree that women should have the freedom to work outside of the home. The widest female-male gaps come from developing countries, while there is virtually no gap in the United States. There are various reasons why men in developing countries may internalise norms against women’s work to a greater extent than women themselves do (Bernhardt et al. 2018, Field et al. 2021), but in settings where this occurs, husbands’ preferences may constrain women’s labour supply. Broadly speaking, there are two ways one might think of overcoming this constraint: raising women’s control in the household, or making husbands more supportive of women’s work. There is evidence on the effectiveness of both approaches.

Field et al. (2021) provide evidence from a large field experiment in India on the first approach of raising women’s control. The authors randomise whether women were given bank accounts, training in account use, and direct deposit of their public sector earnings into their accounts (rather than their husbands’ accounts). Relative to the group that only received accounts, those who also received direct deposits and training worked more in both the public and private sectors. The effect on private sector employment can be explained by a model in which husbands’ preferences constrain women’s employment, but giving women greater financial control raises their bargaining power and overcomes this opposition from husbands.

Heath and Tan (2020) find similar effects from India’s Hindu Succession Act, a law that was phased into different states in India between 1976 and 2005 and enhanced women’s ability to inherit property. In theory, this law would have raised women’s unearned income and thus their control over household decisions. Using age and religious variation in exposure to the law, the authors find the law raised women’s labour supply. A disutility to the husband from the wife’s work is one explanation for this result, though the authors explore an alternative mechanism in a household model that deviates from the efficient benchmark: an increase in a woman’s autonomy in the household increases the share of her income in her control, thereby raising her returns to work and increasing her labour supply. Either mechanism is consistent with the idea that raising women’s control in the household increased their labour supply.

While inheritance rights and financial control could affect women’s work by shifting the underlying distribution of power in the household, Lowe and McKelway (2023) study much lighter-touch interventions that sought to give wives in India more control over their labour supply by simply changing how a women’s employment opportunity was presented to married couples. The authors randomised whether one spouse had the ability to withhold information about the job from the other, thereby preventing the wife from enrolling in it. Among the couples where information was symmetric, they further randomised whether spouses were informed separately or informed together and encouraged to discuss the opportunity. They find no evidence that spouses withhold information, while the discussion treatment significantly reduced take-up of the job. The authors provide suggestive evidence for an explanation that rests on veto power decision making. Relatedly, a cash grant and training programme in Tunisia increased labour supply, but only among women who were assigned to a treatment in which they were not encouraged to invite their partner to training (Gazeaud et al. 2023). More broadly, the evidence suggests that much remains to be learned about intervening directly in the household decision process, but that interventions that shift determinants of women’s bargaining power can be effective in raising their labour supply in some settings.

An alternative approach is to change husbands’ and family members’ opinions about women’s work. McKelway (2023a) partnered with a large carpet manufacturer in India as it introduced new jobs for women, and randomised whether women’s husbands and parents-in-law were given only basic details about the programme, or basic details along with a short (six-minute) promotional video. The video included shots of the workplace and first-hand accounts designed to assuage worries regarding, for instance, safety and ability to manage both work and household chores. Women in both treatment arms were given basic details and shown the video. Showing family members the promotional video increased women’s take-up of the programme from 9% to 16% in the following months. These results suggest women’s employment may be constrained by the opinions of their family members, but also that these opinions could be shifted by a low-cost promotional intervention. Relatedly, Subramanian (2023) finds that reminding female job seekers in Pakistan about discussions with their families makes women less likely to apply to some jobs (specifically, jobs with male supervisors), which is consistent with family opinions constraining female labour supply. In the political sphere, Cheema et al. (2023) find that a campaign to increase political participation only increases women’s voting if men in their household are targeted too.

On the other hand, Dean and Jayachandran (2019) find no effects of a video intervention very similar to that in McKelway (2023a) and also implemented in India. One explanation for these differing results is that Dean and Jayachandran study women who were already employed. Family members of such women would already have a great deal of information about women’s work, which could make them unlikely to be swayed by a short video. Another explanation is that Dean and Jayachandran study results over a one-year time horizon. Indeed, McKelway’s employment effects had faded by one year; she provides suggestive evidence that this is because large amounts of unpaid labour in the home made women’s paid work unsustainable.

Work by Dhar et al. (2022) suggests another way to change husbands’ opinions: reshaping the gender attitudes of adolescent boys so they grow into husbands who are more supportive of women’s labour supply. Adolescence is a natural time to intervene because it is a critical phase in the development of such attitudes. Indeed, Dhar et al. (2022) find that an intervention targeting gender attitudes in secondary schools made boys’ attitudes about women’s employment more progressive over a two-year time horizon. While participants were too young to measure impacts on many economic outcomes, the researchers find some evidence of behavioural change including that boys complete more household chores (though girls do not report a reduction in chores). The researchers plan to conduct a longer-term follow up, which will help shed light on whether these impacts translate to changes in adult employment, marriage, and fertility behaviour.

Norms

A growing empirical literature has studied the role of cultural norms – a society’s informal rules about what constitutes appropriate behaviour – in shaping women’s labour force participation decisions. The first generation of this literature sought to establish that norms, and the underlying attitudes that shape them, matter for women’s economic outcomes. Put differently, researchers sought to establish that economic factors alone could not explain women’s economic decision-making. In a seminal paper, Fernandez and Fogli (2009) find that labour force participation among female second-generation immigrants to the USA is highly correlated with female labour force participation and fertility outcomes in their parents’ country of origin. By examining work behaviour among second-generation immigrants, the researchers are able to identify the role of inherited cultural values holding economic conditions fixed.

The influence of cultural norms on women’s work is also borne out in survey and ethnographic evidence, where researchers find that unequal gender norms within a society are strongly negatively correlated with women’s participation in the labour force (Fortin 2005, Muñoz-Boudet et al. 2013, Giuliano 2021). Norms that constrain women’s work can take on different forms, though often centre on (1) women’s social interactions and freedom of movement; (2) men’s role as family breadwinner; or, (3) men’s and women’s responsibilities regarding child-rearing and other household duties (Jayachandran 2021).

What causes a society to develop norms that constrain women’s economic behavior? Researchers have documented several important historical determinants of gender attitudes, including differences in pre-industrial systems of agriculture. Building on Boserup (1970), Alesina et al. (2013) show, for instance, that pre-industrial tilling practices can help explain gender norms and rates of women’s work today. In particular, some societies prepared agricultural land using ploughs while others used hand tools such as hoes. Because of their upper-body strength, men had a large advantage relative to women in plough tilling; this advantage was smaller when tilling was done with hand tools. As a result, women played a lesser role in agriculture in societies that relied on the plough. Boserup hypothesised that these differences in the gender roles across societies persisted, which Alesina et al. validate by documenting that historical plough use is strongly predictive of both present-day rates of women’s work and attitudes surrounding women in leadership positions. Depth of tillage, which is determined by soil type, also shaped women’s historical participation in agriculture and has been shown to influence both women’s work and gender norms today (Carranza 2014). Modern gender norms can similarly be predicted by pre-industrial economic activities such as hunting-and-gathering (Hansen et al. 2015) and pastoralism (Becker 2021).

Pre-industrial societal characteristics can only explain part of the observed heterogeneity in gender attitudes; there is tremendous variation in local norms even when looking among members of the same cultural or ethnic group. In a study in Odisha, India, Agte and Bernhardt (2023) show, for example, that while there is strong agreement among members of the same Hindu caste group in a given village about whether it is appropriate for women to work outside the home, individuals from that same caste but in the neighbouring village may exhibit a starkly different opinion. Within the Hindu caste system, restrictions on women’s freedom of movement are tied to concepts of “purity”. Agte and Bernhardt find that variation in Hindus’ adherence to caste purity norms can be explained in part by variation in the local presence of Adivasis (the indigenous minority) in their village. Adivasis are outside of the caste system and don’t traditionally follow caste purity norms; as such, Adivasi women are more likely to work. The researchers present evidence to show that there is local norms transmission from Adivasis to Hindus: when Hindus live in Adivasi-majority villages, they report lower adherence to caste purity norms regarding female seclusion and Hindu women are more likely to report paid employment outside the home. At the individual level, transmission of gender attitudes from an outside group has also been documented in schools and other settings where people from different cultural or ethnic backgrounds are placed in close contact (Giuliano 2021).

From a policy perspective, it is important to understand not only the historical determinants of gender norms, but also what works – and what doesn’t work – to change norms and attitudes in the short-run. Researchers have recently begun to build an evidence base on this question. Several studies have sought to directly target individuals’ gender attitudes, with mixed results. In particular, as mentioned earlier, Dean and Jayachandran (2019) found no effects, and McKelway (2023a) only short-term impacts, of a promotional video on men’s attitudes towards women’s work in India, while there is some promise in the approach of targeting men’s attitudes about women’s work, particularly among adolescents, whose ideas are more malleable to change (Dhar et al. 2022).

Another approach to changing gender norms is to target the disconnect between individuals’ privately held beliefs on this topic and their perception of the beliefs held by friends, neighbours, or other community members. Bernhardt et al. (2018) survey households in Madhya Pradesh, India, about both their own beliefs regarding the appropriateness of women working for pay outside the home and their perception of the average belief held by members of their local community. They find that both women and men overestimate local disapproval for women’s work and that the misperception gap is especially large for men. This could lead men to disallow their wives from working for fear of a reputational cost that, in reality, would not come to pass. Bursztyn et al. (2020) offer promising evidence that correcting these misperceptions can lead to an increase in women’s labour force participation. In an experiment in Saudia Arabia, Bursztyn and co-authors similarly find that men systematically overestimate the stigma against women’s work among their peers. For a randomly selected group of men in the sample, the researchers provide accurate information about the true level of disapproval of women’s work within the peer group. In a follow-up survey several months after the information provision, they find that treated men are more likely to report that their wives have applied or interviewed for a job outside the home.

Motivated by the Saudi Arabia evidence, Bursztyn et al. (2023) surveyed men and women from across 60 countries on their personal beliefs about women’s right to work and their perception of the average belief in their society. They find that underestimation of approval for women’s right to work is widespread, which suggests that correcting beliefs could be an effective means of increasing rates of women’s work in many settings.

The above studies describe interventions that aim to increase women’s work via changing gender attitudes; exciting recent work demonstrates that gender attitudes may also shift as a result of an increase in women’s work. First, as discussed in the previous section, Field et al. (2021) find that giving women more control over their income through direct deposits into their own bank accounts increases women’s labour supply. Three years later, women who were induced to work as a result of the intervention also report more liberal attitudes towards women’s employment. Strikingly, the researchers also find that both these women and their husbands perceive a lower level of stigma surrounding women’s work within their community. This may be because participant households directly updated about the strength of social sanctions as a result of their own experience, or because the intervention caused them to observe more women working in their local community, leading them to infer that the social costs of work are lower than they expected.

Ho et al. (2023) similarly find that the experience of working changes women’s own gender attitudes. In an experiment in West Bengal, India, the researchers offer women in rural and urban areas data-entry jobs that can be completed from home and on schedules that accommodate women’s domestic responsibilities. They find that offering women flexibility greatly increases take-up and, as a result of their initial work experience, makes women more willing to accept a less-flexible, outside-the-home job upon completion of the flexible-job intervention. In a short-run follow-up survey, the researchers find that women’s work experience caused them to adopt more liberal attitudes with respect to gender roles inside and outside the home. The results of this study highlight the potential gains to be made from policy interventions that encourage women’s work while accommodating current norms (in this case, norms centred on female seclusion within the home and norms centred on women’s domestic responsibilities).

Taken together, the findings described in Field et al. (2021) and Ho et al. (2023) suggest that short-run interventions that encourage women’s labour force participation could have larger medium- and long-run multiplier effects: if participant women and their families increase their openness to women’s employment as a result of treatment, thereby lowering the average level of opposition to women’s work within a community, this could lead other women to decide to participate in the labour force. The existence and magnitude of this multiplier effect remains an open question for future research.

Psychology

Economists are increasingly using insights from psychology to shed light on topics in development (Kremer et al. 2019). We review evidence on psychological determinants of female labour supply, but note much research remains to be done. To structure our review, we follow DellaVigna’s (2009) classification of behavioural deviations from standard economic models as relating to preferences, beliefs, or decision-making, though we acknowledge that the evidence does not always fit exclusively into one of these categories.

Starting with preferences, Orkin et al. (2023) consider the role of aspirations in determining women’s economic trajectories. Women’s aspirations for their socioeconomic positions could determine their labour supply, but people living in poverty may not have the education or role models needed to set higher aspirations for themselves. The authors randomise whether impoverished women in Kenya were offered a 60-90 minute workshop designed to raise aspirations (while keeping them in reach) and to encourage women to plan and act towards their goals. Compared to a placebo workshop, the aspirations workshop raised female labour supply, as measured on a survey 17 months post treatment. A separate randomly selected subsample was assigned a cash transfer, and the aspirations treatment was also randomly assigned in this subsample. The authors find no effect of the aspirations treatment when cash was given, possibly because cash itself raised aspirations. Ahmed et al. (2023) conducted a related study among final-year female undergraduates in Pakistan, randomising whether subjects were given a light-touch, video-based intervention showcasing employed women they could relate to. This role model treatment left labour supply outcomes largely unaffected for the first 15 months after treatment, though treated women were more likely to be working 18 months post treatment, at the start of Pakistan’s first Covid-19 lockdown, when many primary earners had lost jobs and the opportunity cost of women staying out of the labour market would accordingly have been higher. Evidence from high income countries on women in STEM fields (Carrell et al. 2010, Griffith 2014, Porter and Serra 2020) suggests that role models might also be particularly effective at prompting women to enter male-dominated fields.

In terms of beliefs, McKelway (2023b) studies the role of women’s generalised self-efficacy (GSE) in determining their economic outcomes. GSE refers to beliefs in one’s ability to reach goals. McKelway outlines a model in which low GSE keeps women from pursuing economic goals, which keeps them from learning they could succeed and traps them with low GSE. She randomises whether women in rural India were offered a psychosocial intervention designed to raise GSE or a placebo. Both curricula were delivered across nine sessions held over four weeks. McKelway cross-randomised whether women’s family members were shown a video promoting a female employment opportunity. The GSE treatment alone raised women’s employment. This effect is seen in the months following the treatment but had faded one year later, perhaps due to other constraints on women’s labour supply. The promotion alone also raised employment in the short run, while assignment to both treatments rather than neither had a positive but small and insignificant effect on employment.

Ashraf et al. (2022) study the role of mental imagery in decision-making. Research in psychology and neuroscience suggests visualising future outcomes “in the mind’s eye” can improve the quality of decision-making. The authors randomised would-be entrepreneurs in Colombia to a standard business skills training or to a business training that included imagery-based learning. The trainings were delivered in the second half of 2019 across ten, three-hour sessions. The authors find that relative to the standard training, the imagery-based training significantly increased an index of women’s income and business sales, both before and during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Closely related to psychological constraints to labour supply are constraints imposed by mental illness. Mental illness could affect labour supply through a variety of channels, for instance making work physically costlier or crippling individuals with self-doubt. A meta-analysis finds treating mental illness improves labour market outcomes in developing countries (Lund et al. 2022), but relatively less is known about effects for women in particular. One sort of mental illness that differentially affects women is depression around the time of childbirth. In a randomised trial, Baranov et al. (2020) evaluate psychotherapy for prenatally depressed mothers in Pakistan. Seven years post treatment, treated women were less likely to be depressed and had greater financial empowerment. They were also more likely to be working, but the effect is not significant, in part because very few women in the sample work. Angelucci and Bennett (2024) similarly do not find that medication increases the labour supply of depressed women in India.

Safety and harassment

There is a nascent but fast-growing literature on how harassment and perceptions of safety outside the home affect women’s economic choices. Sexual harassment ranges from verbal harassment (such as catcalls, whistling or emotionally abusive statements) to visual harassment (such as leering or staring) to physical harassment (such as men exposing themselves, groping, other forms of touching, assault, or being forced into a sexual act). Such harassment affects women’s educational attainment, their physical mobility and labour market outcomes. Here we focus on the harassment women face from the beginning to the end of their journey into the labour force, starting with the harassment that is perpetrated by staff or fellow students in educational institutions, to the harassment they face from strangers or service providers in public spaces and finally the harassment by bosses or co-workers in a workplace.

In educational institutions

Violence in schools is a major problem around the world. For example, three out of ten adolescents in Latin America have suffered some form of sexual harassment in schools, and 1.1 million girls within the region have suffered some form of sexual violence (UNICEF 2017, UNICEF 2018). Parkes and Heslop (2011) show that students experience violence in many forms in schools in Ghana, Kenya, and Mozambique, ranging from whipping and beating to peeping and sex in exchange for goods. Additionally, most sexual violence at schools is perpetrated by peers while most of the physical violence is perpetrated by teachers (Parkes and Heslop 2011, Together for Girls 2021a, Together for Girls 2021b, Devries et al. 2018, Samati 2021).

Such harassment and violence in schools affects students’ learning outcomes. Most of the existing evidence on the negative effects of violence in schools is based on studies conducted in high-income countries. Being a victim of violence in school is negatively associated with learning outcomes (Ponzo 2013, Eriksen et al. 2014, Contreras et al. 2016), and positively associated with student dropout, student mobility, and absenteeism (Brown and Taylor 2008, Dunne et al. 2013, Solotaroff and Pande 2014). Evidence also documents lasting negative effects over the life cycle both in the likelihood of employment during adulthood and dimensions of individual well-being related to mental health (Brown and Taylor 2008, Sarzosa and Urzúa 2021). In low-income countries where there are likely additional constraints to educational attainment, the small amount of evidence is more mixed. Using a sample that represents more than 80% of girls aged 15-19 across 20 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Evans et al. (2023) compare girls in and out of school, but they do not find any statistically significant differences in harassment experiences of girls by school enrollment. Palermo et al. (2019) on the other hand analyse surveys of violence against children from six countries and find mixed results of the association between school enrolment and the risk of violence.

There has been an increase in both the programmes to address violence in schools as well as evidence on the efficacy of these programmes in recent years. Karmaliani et al. (2020) conducted a randomised controlled trial to evaluate a structured play-based life-skills intervention implemented in schools in Hyderabad, Pakistan, and found that it led to significant decreases in self-reported peer violence victimisation, perpetration, and depression. Smarrelli (2023) studies the effects of investing in school principals’ skills to manage school violence in Peru by training them in identification and monitoring of different forms of violence between students and teacher-to-student, adoption of response protocols, and the implementation of positive discipline strategies. She finds that this training increased reported violence and reduced school switching or student mobility by 20% for students in treated schools relative to control schools, but finds no effect on school dropout or learning outcomes. Also in Peru, Gutierrez et al. (2018) find that increasing awareness among students about the negative consequences of harassment and encouraging them to stand against this problem and facilitating students' ability to report violent incidents led to positive outcomes: the intervention reduced students' bystander behaviour and increased their willingness to report violence, reduced the likelihood of changing schools and of dropping out, and improved student achievement in standardised tests in the medium term. Amaral et al. (2023a) test a combination of teacher and student training in Mozambique and find that it reduced sexual violence perpetrated by teachers towards girls by almost 50%. There is also evidence in high-income countries on state-level interventions such as anti-bullying laws that have been found to be effective in reducing victimisation and improving students’ mental health (Rees et al. 2022).

Women also face sexual harassment in higher educational institutions. For example, in India one in ten respondents reported being sexually assaulted by a person from their educational institutions (Mukherjee and Dasgupta 2022) while in the US, 22% of college women have experienced dating violence and nearly 20% have experienced completed or attempted sexual assault since entering college (Bondestam and Lundqvist 2020). There is very limited work in economics on understanding the extent, causes, consequences of, or policy solutions for such harassment. A few exceptions to this are the work by Lindo et al. (2018) and Sharma (2023). Lindo et al. (2018) exploit the timing of college football games and show that increased revelry leads to higher rates of sexual assault in college-aged victims (17-24 years) in the US. Sharma (2023) evaluates the effectiveness of class-based sexual harassment awareness training with university students in Delhi and finds that training men reduces women’s reports of sexual harassment by classmates, led to no improvement in men’s attitudes towards women and a long-lasting reduction in romantic relationships between men and women within the classroom.

In public spaces

Harassment in public spaces is pervasive. For example 86% of women in Brazil, 79% in India, and 86% in Thailand have been subjected to harassment in public in their lifetime (ActionAid 2016). Women’s own safety concerns or their parents’ concerns related to safety while traveling have been alluded to as a potential mechanism affecting women’s access to schooling and skills training programmes (Mukherjee 2012, Burde and Linden 2013, Muralidharan and Prakash 2017, Jacoby and Mansuri 2015, Cheema et al. 2022, Alba-Vivar 2023). More directly, lack of safety has been found to affect women’s mobility patterns. Christensen and Osman (2023) use data on transport mode usage and safety perceptions in Cairo, Egypt, to show that women substitute away from unsafe modes of public transport when provided with fare subsidies for Uber, a ride-hailing service. Perceived travel safety affects women’s higher educational choices. Borker (2021) shows that women choose lower quality colleges than equally high achieving men in Delhi, India, to travel by a safer route to university. She finds that women are willing to choose a college that is in the bottom half of the quality distribution over a college in the top 20% for a route that is perceived to be one standard deviation (SD) safer. Men on the other hand are only willing to go from a top 20% college to a top 30% college for an additional SD of perceived travel safety.

Expected harassment in public spaces has also been shown to be correlated with women’s labour force participation on the extensive margin. Women in India are far less likely to seek outside employment in neighbourhoods where the self-reported level of sexual harassment is high (Chakraborty et al. 2018) or where local media reports of sexual assaults are high (Siddique 2022). In Lahore, Pakistan, Field and Vyborny (2022) show that provision of a women-only transport service to and from work increased job search behavior for women relative to mixed-transport offer. Additionally, Buchmann et al. (2023) highlights how provision of safe transport can also increase the demand for women workers by reducing their perceived costs to employers who exhibit paternalistic discrimination. These results raise the possibility that in environments where women’s safety and mobility is severely constrained, it could be profitable for businesses to offer transportation to their female employees.

In recognition of women’s safety in public spaces being an important constraint limiting not only women’s physical mobility but also their economic mobility, several policy solutions have been evaluated. Investment in large-scale infrastructure projects that make it faster and safer for women to use public transport have been found to improve women’s economic outcomes. Martinez et al. (2020) show that Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and elevated light rail investments in the metropolitan region of Lima, Perú, led not only to an increase in the use of public transport by women closer to the new transport system compared to those father away, but also a 10 percentage point increase in the probability of being employed for women and an increase of 23% in the earnings per hour; men did not experience any such gains. Kondylis et al. (2020) evaluated the women’s only cars in the Rio de Janeiro supervia and found that 20% of female riders are willing to pay 20% more for a reserved space, and over a one-year period, an average female rider is willing to pay the equivalent of 0.35% of the minimum wage to travel in women-only cars.

What policies have been proposed to address this harassment? While being one of the easier policies to implement, segregated spaces can have unintended consequences, where opting for strict gender-based segregated public transport is seen as the “proper” choice for women commuters, and women traveling outside the reserved spaces are seen as provoking harassment or “asking for it” (Kondylis et al. 2020). Segregation has also been found to reduce sexual violence faced by women but increase nonsexual aggression in the male compartments such as insults or shoving (Aguilar et al. 2021). Fare subsidies targeting women have been found to be effective in increasing the take-up and use of the subsidised mode of transport (Borker et al. 2020), but there is significant heterogeneity in the effects based on women’s educational level and socio-economic status. Such subsidies have also been found to increase job search behaviour for unemployed women (Chen et al. 2023). Amaral et al. (2023b) find that patrolling by police that targets sexual harassment in public spaces leads to a reduction in severe forms of harassment by 27% and improves women’s mobility, highlighting how creating safe spaces can help women move more freely.

At work

Harassment at work affects a significant number of women, although the prevalence varies across countries. For example, 12.6% women in Sweden report being sexually harassed at their workplace in the last 12 months based on a bi-annual nationally representative survey of the employed population aged 16-64 years (Folke and Rickne 2022) while 90% of women interviewed across 2,910 organisations in Uganda report being sexually harassed by their male superiors at work (ITUC 2014). Younger women, women with temporary contracts, women in leadership positions, and those in male-dominated workplaces are more likely to be harassed at work (Agbaje et al. 2021, Folke and Rickne 2022). Much like all reported data on violence against women, workplace harassment also suffers from underreporting. Cheng and Hsiaw (2022) develop a model in which harassment is underreported if there are multiple victimised individuals because of coordination problems. Dahl and Knepper (2021) examine causes of underreporting, providing evidence that US employers use the threat of retaliatory firing to coerce workers not to report sexual harassment.

Given that rules around worker safety are more likely to be lacking altogether and/or imperfectly enforced in developing contexts, one might expect both rates of unsafe working conditions and underreporting of such conditions to be even more prevalent in these settings, with worse consequences for workers. Indeed, Boudreau et al. (2023) document that unsafe working conditions and harassment are prevalent in the Bangladeshi garment sector. This sector is an important employer of women across developing countries, employing over 60 million women workers (RISE 2023). To incentivise workers to truthfully report instances of harassment, Boudreau et al. (2023) provide them with plausible deniability by falsely coding some of their reports of no harassment as true. The authors find that 13.5% of workers report being threatened in the workplace, 5.7% report being subject to physical harassment, and 7.7% report being subject to sexual harassment. And what makes the issue even more problematic is that reporting could be made worse by well-intentioned interventions like social norms training for potential bystanders, which can potentially inspire “free-riding” among participants who perceive that someone else will intervene when they learn that the majority of their peers disapprove of an activity (Rhodes et al. 2023).

In terms of the consequences of harassment, we know very little about its effect on workers’ labour supply and well-being, and policies to address it. From the limited evidence that exists, we know that harassment limits Swedish women from applying to jobs where they are the gender minority and women who face harassment are more likely to take a pay cut to switch to jobs with more women colleagues (Folke and Rickne 2022). Consistent with these results, in Finland, Adams-Prassl et al. (2022) find that violence against women at work reduces women at the firm both by reducing the number of new women hires as well as women leaving the firm. They also show that women managers are more likely than male managers to fire perpetrators thereby mitigating the negative impacts of harassment on women. Interestingly, one way to increase the number of women managers is by implementing sexual harassment training programmes for managers (Dobbin and Kalev 2019).

Having women in managerial roles has other positive benefits on female employees. For instance, plausibly random assignment to a female manager in a Bangladeshi garment factory increases female workers’ say in decisions in their own households (Uckat 2023). In the United States, female principals and superintendents also reduce the gender wage gap that arises when flexibility is introduced into the wage-setting process among public school teachers (Biasi and Sarsons 2022).

Workplace Amenities

Despite large improvements in women's education and declines in their fertility over the last few decades, women in developing countries continue to work and earn substantially less than men. Across a series of surveys, women identify inadequate workplace conditions, or “amenities”, as an important barrier to their participation. For example, over 30% of working women cite low workplace safety or flexibility as their main challenge (Ray et al. 2017). Over 30% of married Indian women report wanting to enter the labour market, but only if offered part-time jobs (Fletcher et al. 2017). And women are willing to accept a 14% pay cut for shorter commutes (Le Barbanchon et al. 2021).[2] In other words, modern workplaces are ill suited to the needs of working women, and especially those of working mothers.

In this section, we begin by describing the current state of research on the amenities that crucially underlie women's participation and retention in the labour market in developing countries. We subsequently outline how the prevalence of jobs that do not provide these amenities, and which are therefore ill suited to the needs of working women, can generate gender wage gaps, both by directly reducing women’s productivity, and by conferring employers with higher monopsony power over them. Finally, we examine the role of various demand-side institutions in influencing the design of jobs, how they can change workplaces to become more female-friendly, and the consequences of doing so.

Amenities

Women in developing countries regularly bear the double burden of work and home, suggesting that amenities that enable them to balance the two could be instrumental in increasing women's participation in the labour market. Several recent papers find evidence in favour of this hypothesis.

Corradini et al. (2023) study a reform at Brazil’s largest trade union federation (the Central Unica dos Trabalhadores, or CUT), that caused a fifth of Brazilian employers to increase their provision of female-friendly amenities – including expansions of maternity leave, flexibility, and childcare. The authors find that a 19% increase in female-friendly amenities increased women’s retention at affected employers by 10% and caused women to queue for jobs there (a 10% increase in women who have probationary contracts, which employers use to screen job applicants).

In addition to amenities that improve work environments in the office, flexible work arrangements that enable women to work from home instead of the office are also shown to dramatically increase women’s labour force participation. In two randomised controlled trials in India, Ho et al. (2023) and Jalota and Ho (2023) evaluate women's willingness to take up and pay for flexible work. Ho et al. (2023) find that women who are offered the option to perform gig work from home are three times as likely to take up work (48%) compared to women who are offered the same job in an office (15%). In Jalota and Ho (2023), a similarly flexible work arrangement doubles women’s take-up of gig work, from 27% to 56%. The latter also find that women are willing to forego substantial earnings to avoid working from the office. Doubling wages has no effect on their take-up of office-based work. The McKelway (2023a) study discussed earlier finds, similarly, that informing women and their families about the flexible nature of a job increases take-up.

All four of these papers demonstrate the outsized importance of flexibility in increasing women's labour market participation over the short run. However, the extent to which these gains are sustained over time remains an open question. Corradini et al. (2023) track workers over three years and find persistent improvements in their labour market participation, especially following motherhood. McKelway (2023a) finds no effect on employment one year following the intervention, at least partly because the women in her setting find it difficult to manage work alongside home. By contrast, Ho et al. (2023) find that flexible jobs may serve as a gateway to more inflexible, office-based work by changing household norms regarding the appropriateness of women's work. Women exposed to flexible jobs are 6 percentage points more likely to accept office-based work two to three months later.

A second amenity that is especially valuable to women is safety. We discussed the evidence that harassment from coworkers and supervisors discourages women’s labour supply in Section 2.5. On occupational safety, Boudreau (2022) finds that very few Bangladeshi garment factories were complying with a national mandate to set up occupational safety and health (OSH) committees as of 2019. The Bangladeshi government had mandated these committees following the tragic collapse of a garment factory in the Rana Plaza complex in Dhaka, which killed 1134 garment workers. Although few factories complied with the OSH mandate as of 2019, experimentally inducing some factories to comply improved both safety and, importantly, worker satisfaction.

A third amenity that influences women's choice to participate in the labour market and, especially, their choice of employer, given the harassment in public spaces we document earlier, is safe and short commutes. Given the low levels of public safety prevalent in some developing contexts, women may disproportionately choose employers that are close to their homes.[3] Le Barbanchon et al. (2021) find that French women are willing to take a 14% pay cut relative to men for shorter commutes – which constitutes perhaps a lower bound on the willingness to pay among women in developing countries. As discussed in Section 2.5, a lack of safety on public transportation discourages women from choosing high quality colleges (Borker 2021), and being offered safe transportation affects women’s labour supply (Field and Vyborny 2022, Buchmann et al. 2023). Commuting constraints affect women’s earnings. In Brazil, Sharma (2023) finds that unsafe commutes to alternative employers make women substantially less likely to leave their current employer following a wage cut, giving employers higher monopsony power over them and generating a 10 percentage point gender wage gap among equally productive workers.

Two other amenities merit mention. First, women have an affinity for working with other women, making the presence of female co-workers a valued amenity. This “amenity” could reflect that women possess a strong preference for female co-workers, but it could also reflect traditional gender norms that restrict women's interactions with men, or practical safety constraints that lead them to avoid predominantly male workplaces. Chiplunkar and Goldberg (2021) document that, consistent with women's affinity for working with female co-workers, female entrepreneurs find it substantially easier to recruit female workers compared to male entrepreneurs. The authors show that female entrepreneurs face higher barriers to starting and expanding businesses than men. Combined, these two facts imply that reducing barriers to female entrepreneurship may indirectly increase female labour force participation. The paper’s simulations suggest that eliminating all excess barriers to female entrepreneurship would increase the number of female entrepreneurs five-fold (to 11%), and double female labour force participation (to 60%). Expanding the networks of female entrepreneurs through online networking also improves business outcomes (Asiedu et al. 2023).

Finally, workers likely value being treated with dignity and having voice. Women may especially value these attributes. While very few papers in economics investigate the importance of dignity at work, worker voice has received more attention.[4] Adhvaryu et al. (2022) implement a randomised controlled trial in the Indian garment sector to evaluate the effect of increasing worker voice on turnover and absenteeism. They find that workers, a large majority of whom are women, who are asked to provide feedback after a disappointing wage hike are 19% less likely to quit five months following the voice intervention, and less likely to be absent from work.

Amenities and gender wage gaps

In sum, desirable features of the work environment that improve it for women crucially underlie their choice to participate in the labour market at all, to remain in it, and their choice of employer. Even so, jobs are slow to adapt to the needs of working women (Goldin 2014). For example, only 30% of collective bargaining contracts in Brazil feature any female-friendly clause pertaining to maternity leave, childcare, flexible work arrangements, or the prevention of harassment and discrimination (Corradini et al. 2023). And although work from home opportunities are growing following the COVID-19 pandemic, the vast majority of jobs remain inflexible (Datta et al. 2023). Finally, nearly 8% of garment workers in a large Bangladeshi garment factory are subject to sexual harassment (Boudreau et al. 2023).

That few jobs are well-suited to women's needs limits not only their participation but also generates gender wage gaps. First, it causes women to become less productive in their current jobs. Women are more likely to drop out of and be absent from inflexible jobs, thereby making them less reliable workers (Ho et al. 2023, McKelway 2023a). They are also less likely to return to work following motherhood (Corradini et al. 2023, Kleven et al. 2023), and suffer large earnings penalties when they do become mothers (Kleven et al. 2023). Although less empirically documented, unsafe work environments and commutes surely also diminish worker productivity.

Second, the fact that women have fewer good (high amenity) jobs than men, and are thus less likely to switch employers when underpaid by their current employer, can confer employers with higher monopsony power over women. Sharma (2023) investigates the extent to which gender differences in monopsony power explain the gender wage gap in Brazil, and the sources of this differential monopsony power over women. Using firm-specific demand shocks in the textile and clothing manufacturing industry, she documents that women are substantially less likely than men to leave their employer following a wage cut. The resulting gender difference in monopsony power would generate an 18 percentage point gender wage gap among equally productive workers, and explain over half the observed gender wage gap. Of this, she finds that about half the monopsony gender wage gap is attributable to women's stronger preference for their specific employer, at least partly due to their inability to commute to a new employer when their neighbourhood is unsafe. The remaining half of the monopsony gender gap is explained by the fact that good jobs for women are highly concentrated in the textile and clothing manufacturing industry. By contrast, desirable jobs for men are not similarly concentrated.

What causes these jobs to persist/how can we change them?

Which institutions determine how workplaces are designed, and how can they change to become more female-friendly? Recent research has investigated the importance of several demand-side institutions in making workplaces more female-friendly and the associated tradeoffs.

First, the government can implement female-friendly policies. Field et al. (2021) study the importance of financial inclusion and increasing women's control over their earnings by depositing salaries in women's own accounts as opposed to in their husband's account. In a randomised controlled trial that implements this policy for India's national employment guarantee programme, the authors find a 0.11 standard deviation increase in a measure of women's engagement with the labour market. Garcia et al. (2023) show that providing free childcare increases mothers' labour supply by 6.4 percentage points. Finally, although we lack evidence on the labour supply effects of maternity leave policies in developing countries, research in developed countries finds that they enable women to spend more time with their children with limited long-term effects on employment or earnings (Lalive and Zweimüller 2009, Schönberg and Ludsteck 2014, Dahl et al. 2016).

Second, unions can bargain for improved female-friendly amenities. Corradini et al. (2023) show that when a reform caused Brazil's largest trade union federation (CUT) to prioritise women's needs in collective bargaining, this improved female-friendly amenities by 19% at employers who were negotiating with CUT-affiliated unions compared to those negotiating with a different union. Women valued the increase in amenities, and became less likely to quit and more likely to queue for jobs at affected employers. However, surprisingly, the gain in amenities did not come at the expense of either women or men's wages, employment, or firm profits. Together, these findings suggest that employers were inside their frontier provision of female-friendly amenities.

Third, and increasingly, international buyers can induce their suppliers to improve amenities. Boudreau (2022) finds that buyer-induced compliance with OSH committees in Bangladesh has small, positive effects on safety and worker satisfaction, without reducing wages or employment. Alfaro-Ureña et al. (2022) find that responsible sourcing policies in Costa Rica cause affected employers to increase the wages of low wage workers. However, they also cause employers to reduce employment, which in turn has negative spillover effects on the wages of workers at unaffected employers. Bossavie et al. (2023), by contrast, find that factories exposed to greater international scrutiny improved working conditions and wages, but did not find employment losses. They argue that if firms have monopsony power, external pressure to raise total compensation need not come at the expense of jobs.

Finally, firms can change their own policies. For example, Kuhn and Shen (2013) find that when a Chinese jobs board disallowed employers from explicitly requesting workers of a specific gender, employers became much more receptive to applications from workers of a different gender. This improved the quality of matches and led to win-win gains for both workers and employers. Of course, not all changes have a win-win element: Atkin et al. (2023) find that switching entirely to a work from home policy would increase participation among workers who have greater household responsibilities, but would reduce worker productivity by 18%.

Taken together, existing research on the role of institutions in improving workplaces for women offers a promising insight—that institutions can effectively improve female-friendly amenities, with positive effects on female labour force participation and retention, and the potential to reduce employers' monopsony power over women. A surprising conclusion of some recent studies is that these improvements in female-friendly amenities can manifest without observed tradeoffs in workers' wages, employment, or firm profits. Thus, they suggest the possibility that providing female-friendly amenities is both profitable to employers and beneficial to employees (Boudreau 2022, Corradini et al. 2023).

One possible explanation for these findings is that frictions in the bargaining process or in aggregating workers’ interests to the union or firm level (e.g. information or contracting frictions) yields the possibility for win-win situations once attention is refocused on previously ignored issues. An alternative explanation is that, although women are increasingly entering the labour force, employers are only slowly adapting workplaces to the needs of women workers. In either case, the findings imply that policies to elevate worker voice within labour market institutions can effectively reduce gender gaps in participation and compensation. Even more broadly, they highlight the possibility that government policies to improve female amenities—such as universal childcare—can usher a transition to the frontier provision of amenities without necessarily reducing wages or employment. Of course, not all policies that improve workplaces for women will be costless—for example, shifting entirely to WFH arrangements could dramatically lower productivity (Atkin et al. 2023, Ho et al. 2023). Studying how best to mitigate the costs of these policies remains a fruitful avenue for future work.

References

Aaronson D, R Dehejia, A Jordan, C Pop-Eleches, C Samii and K Schulze (2021), “The effect of fertility on mothers’ labor supply over the last two centuries.” The Economic Journal, 131(633): 1-32.

ActionAid (2016), “Three in four women experience harassment and violence in UK and global cities.”

Adams-Prassl, A, K Huttunen, E Nix, and N Zhang (2022), "Violence against women at work."

Addati, L, U Cattaneo, V Esquivel, and I Valarino (2018), "Care work and care jobs for the future of decent work," International Labour Organisation (ILO).

Adhvaryu, A, T Molina, and A Nyshadham (2022), "Expectations, Wage Hikes and Worker Voice," The Economic Journal, 132: 1978–1993.

Ajayi, K F, A Dao, and E Koussoubé (2022), "The Effects of Childcare on Women and Children."

Agbaje, O S, C K Arua, J E Umeifekwem, P C I Umoke, C C Igbokwe, T E Iwuagwu, C N Iweama, E L Ozoemena, and E N Obande-Ogbuinya (2021), "Workplace gender-based violence and associated factors among university women in Enugu, South-East Nigeria: an institutional-based cross-sectional study," BMC Women's Health, 21: 124.

Agte, P, and A Bernhardt (2023), "The Economics of Caste Norms: Purity, Status, and Women’s Work in India."

Aguilar, A, E Gutierrez, and P S Villagran (2021), “Benefits and Unintended Consequences of Gender Segregation in Public Transportation: Evidence from Mexico City’s Subway System,” Economic Development and Cultural Change, 69: 1379–1410.

Ahmed, H, M Mahmud, F Said, and Z Tirmazee (2023), “Encouraging Female Graduates to Enter the Labor Force: Evidence from a Role Model Intervention in Pakistan,” Economic Development and Cultural Change, Advance online publication.

Alba-Vivar, F (2023), “Opportunity Bound: Transport and Access to College in a Megacity.”

Alesina, A, P Giuliano, and N Nunn (2013), "On the origins of gender roles: Women and the plough," The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128: 469–530.

Alfaro-Ureña, L, B Faber, C Gaubert, I Manelici, and J P Vasquez (2022), “Responsible Sourcing? Theory and Evidence from Costa Rica,” Working Paper.

Amaral, S, A Garcia-Ramos, S Gulesci, S Oré, A Ramos, and M M Sviatschi (2023), “Report: Tackling Gender-Based Violence in Schools: Experimental Evidence from Mozambique.”

Amaral, S, G Borker, N Fiala, A Kumar, N Prakash, and M M Sviatschi (2023), “Sexual Harassment in Public Spaces and Police Patrols: Experimental Evidence from Urban India,” NBER Working Paper no. 31734.

Angelucci, M and D Bennett (2024), “The economic impact of depression treatment in India: Evidence from community-based provision of pharmacotherapy.” American Economic Review, 114(1): 169-198.

Angrist, J (2002), “How Do Sex Ratios Affect Marriage and Labor Markets? Evidence from America's Second Generation,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117: 997–1038.

Ashraf, N, G Bryan, A Delfino, E Holmes, L Iacovone, and A Pople (2022), “Learning to See the World’s Opportunities: The Impact of Imagery on Entrepreneurial Success,” Working Paper.

Asiedu, E, M Lambon-Quayefio, F Truffa, and A Wong (2023), “Female Entrepreneurship and Professional Networks,” PEDL Working Paper.

Atkin, D, A Schoar, and S Shinde (2023), "Working from home, worker sorting and development," NBER Working Paper no. w31515.

Bandiera, O, N Buehren, R Burgess, M Goldstein, S Gulesci, I Rasul, and M Sulaiman (2020), "Women’s empowerment in action: evidence from a randomized control trial in Africa," American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 12: 210–259.

Baranov, V, S Bhalotra, P Biroli, and J Maselko (2020), "Maternal Depression, Women's Empowerment, and Parental Investment: Evidence from a Randomized Controlled Trial," American Economic Review, 110: 824–859.

Becker, A (2021), "On the economic origins of restricting women’s promiscuity," Review of Economic Studies.

Becker, G S (1965), "A Theory of the Allocation of Time,” The Economic Journal, 75: 493–517.

Becker, G S (1981, Enlarged ed., 1991), "A Treatise on the Family", Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bernhardt, A, E Field, R Pande, N Rigol, S Schaner, and C Troyer-Moore (2018), "Male social status and women’s work," AEA Papers and Proceedings, 108: 363–367.

Berniell, I, L Berniell, D De la Mata, M Edo, and M Marchionni (2021), "Gender gaps in labor informality: The motherhood effect," Journal of Development Economics, 150: 102599.

Bertrand, M, C Goldin, and L F Katz (2010), "Dynamics of the gender gap for young professionals in the financial and corporate sectors," American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2: 228–255.

Biasi, B, and H Sarsons (2022), "Flexible wages, bargaining, and the gender gap," The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 137: 215–266.

Bjorvatn, K, D Ferris, S Gulesci, A Nasgowitz, V Somville, and L Vandewalle (2022), "Childcare, labor supply, and business development: Experimental evidence from Uganda."

Bloom, D E, D Canning, G Fink, and J E Finlay (2009), "Fertility, female labor force participation, and the demographic dividend," Journal of Economic Growth, 14: 79–101.

Bondestam, F, and M Lundqvist (2020), "Sexual harassment in higher education – a systematic review," European Journal of Higher Education, 10: 397–419.

Borker, G (2021), "Safety first: Perceived risk of street harassment and educational choices of women," World Bank Policy Research Working Paper no. 9731.

Borker, G, G Kreindler, and D Patel (2020), "Women’s Urban Mobility Barriers: Evidence from Delhi’s Free Public Transport Policy," IGC Final Report, London: International Growth Centre.

Bossavie, L, Y Cho, and R Heath (2023), "The effects of international scrutiny on manufacturing workers: Evidence from the Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh," Journal of Development Economics, 163: 103107.

Boserup, E (1970), Woman’s Role in Economic Development, London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd.

Boudreau, L (2022), "Multinational enforcement of labor law: Experimental evidence from Bangladesh’s apparel sector."

Boudreau, L E, S Chassang, A Gonzalez-Torres, and R M Heath (2023), "Monitoring harassment in organizations," NBER Working Paper no. w31011.

Branson, N, and T Byker (2018), "Causes and consequences of teen childbearing: Evidence from a reproductive health intervention in South Africa," Journal of Health Economics, 57: 221–235.

Brown, S, and K Taylor (2008), "Bullying, education and earnings: Evidence from the National Child Development Study," Economics of Education Review, 27: 387–401.

Buchmann, N, C Meyer, and C D Sullivan (2023), "Paternalistic Discrimination."

Burde, D, and L L Linden (2013), “Bringing education to Afghan girls: A randomized controlled trial of village-based schools,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 5: 27–40.

Bursztyn, L, A L Gonzalez, and D Yanagizawa-Drott (2020), "Misperceived social norms: Women working outside the home in Saudi Arabia," American Economic Review, 110: 2997–3029.

Bursztyn, L, A Cappelen, B Tungodden, A Voena, and D Yanagizawa-Drott (2023), "How Are Gender Norms Perceived?" Working Paper.

Canning, D, and T P Schultz (2012), "The economic consequences of reproductive health and family planning," The Lancet, 380: 165–171.

Carranza, E (2014), "Soil endowments, female labor force participation, and the demographic deficit of women in India," American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 6: 197–225.

Carrell, S E, M E Page, and J E West (2010), “Sex and science: How professor gender perpetuates the gender gap,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125: 1101–1144.

Chakraborty, T, A Mukherjee, S R Rachapalli, and S Saha (2018), “Stigma of Sexual Violence and Women’s Decision to Work,” World Development, 103: 226–238.

Chen, Y, K Cosar, D Ghose, S Mahendru, and S Sekhri (2023), “Gender-Specific Commuting Costs and Female Time Use: Evidence from India’s Pink Slip Program.”

Cheema, A, A I Khwaja, M F Naseer, and J N Shapiro (2022), “Glass Walls: Experimental Evidence on Access Constraints Faced by Women.”

Cheema, A, S Khan, A Liaqat, and S K Mohmand (2023), "Canvassing the gatekeepers: A field experiment to increase women voters’ turnout in Pakistan," American Political Science Review, 117: 1–21.

Cheng, I H, and A Hsiaw (2022), “Reporting sexual misconduct in the #MeToo era,” American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 14: 761–803.

Chiappori, P‐A, B Fortin, and G Lacroix (2002), “Marriage Market, Divorce Legislation, and Household Labor Supply,” Journal of Political Economy, 110: 37–72.

Chiplunkar, G, and P K Goldberg (2021), "Aggregate implications of barriers to female entrepreneurship," NBER Working Paper no. w28486.

Christensen, P, and A Osman (2023), “The Demand for Mobility: Evidence from an Experiment with Uber Riders,” NBER Working Paper no. 31330.

Clark, S, C W Kabiru, S Laszlo, and S Muthuri (2019), "The impact of childcare on poor urban women’s economic empowerment in Africa," Demography, 56: 1247–1272.

Contreras, D, G Elacqua, M Martinez, and A Miranda (2016), “Bullying, identity and school performance: Evidence from Chile,” International Journal of Educational Development, 51: 147–162.

Corradini, V, L Lagos, and G Sharma (2023), "Collective bargaining for women: How unions can create female-friendly jobs."

Dahl, G B, and M M Knepper (2021), “Why is Workplace Sexual Harassment Underreported? The Value of Outside Options Amid the Threat of Retaliation,” IZA Discussion Papers no. 14740.

Dahl, G B, K V Løken, M Mogstad, and K V Salvanes (2016), "What is the case for paid maternity leave?" Review of Economics and Statistics, 98: 655–670.

Datta, N, C Rong, S Singh, C Stinshoff, N Iacob, N S Nigatu, M Nxumalo, and L Klimaviciute (2023), "Working Without Borders-The Promise and Peril of Online Gig Work: Short Note Series Number Two-Is Online Gig Work an Opportunity to Increase Female Labor Force Participation?"

Dean, J, and S Jayachandran (2019), "Changing family attitudes to promote female employment," AEA Papers and Proceedings, 109: 138–142.

Delecourt, S, and A Fitzpatrick (2021), "Childcare matters: Female business owners and the baby-profit gap," Management Science, 67: 4455–4474.

Delecourt, S, A Marchenko, A Fitzpatrick, and L Lowe (2023), "Sticky constraints: Business location, competition, and the gender profit gap."

DellaVigna, S (2009), "Psychology and Economics: Evidence from the Field," Journal of Economic Literature, 47: 315–372.

Devries, K, L Knight, M Petzold, K G Merrill, L Maxwell, A Williams, C Cappa, K L Chan, C Garcia-Moreno, N Hollis, H Kress, A Peterman, S D Walsh, S Kishor, A Guedes, S Bott, B C B Riveros, C Watts, and N Abrahams (2018), “Who perpetrates violence against children? A systematic analysis of age-specific and sex-specific data,” BMJ Paediatrics Open, 2.

Dhar, D, T Jain, and S Jayachandran (2022), "Reshaping adolescents’ gender attitudes: Evidence from a school-based experiment in India," American Economic Review, 112: 899–927.

Dobbin, F, and A Kalev (2019), “The promise and peril of sexual harassment programs,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116: 12255–12260.

Donald, A, S Lowes, and J Vaillant (2023), "Experimental Evidence on Rural Childcare Provision."

Dube, A, S Naidu, and A D Reich (2022), “Power and dignity in the low-wage labor market: Theory and evidence from Wal-Mart workers” NBER Working Paper no. w30441.

Dunne, M, R Sabates, C Bosumtwi-Sam, and A Owusu (2013), “Peer Relations, Violence and School Attendance: Analyses of Bullying in Senior High Schools in Ghana,” Journal of Development Studies, 49: 285–300.

Eriksen, T L M, H S Nielsen, and M Simonsen (2014), “Bullying in elementary school,” Journal of Human Resources, 49: 839–871.

Evans, D K, P Jakiela, and H A Knauer (2021), "The impact of early childhood interventions on mothers," Science, 372: 794–796.

Evans, D K, S Hares, P A Holland, and A Mendez (2023), “Adolescent Girls’ Safety In and Out of School: Evidence on Physical and Sexual Violence from across Sub-Saharan Africa,” Journal of Development Studies, 59: 739–757.

Fernandez, R, and A Fogli (2009), "Culture: An empirical investigation of beliefs, work, and fertility," American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 1: 146–177.

Field, E, and K Vyborny (2022), "Women's Mobility and Labor Supply: Experimental Evidence from Pakistan," Asian Development Bank Economics Working Paper Series No. 655.

Field, E, R Pande, N Rigol, S Schaner, and C Troyer Moore (2021), "On her own account: How strengthening women’s financial control impacts labor supply and gender norms," American Economic Review, 111: 2342–2375.

Finlay, J E (2021), "Women’s reproductive health and economic activity: A narrative review," World Development, 139: 105313.

Fletcher, E, R Pande, and C M T Moore (2017), "Women and work in India: Descriptive evidence and a review of potential policies."

Folke, O, and J Rickne (2022), “Sexual Harassment and Gender Inequality in the Labor Market,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 137: 2163–2212.

Fortin, N (2005), "Gender Role Attitudes and the Labor-market Outcomes of Women across OECD Countries," Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 21: 416–438.

Garcia, J, M Mello, and R Latham-Proença (2023), "Free Childcare and the Motherhood Penalty: Evidence from São Paulo."

Gazeaud, J, N Kahn, E Mvukiyehe, and O Sterck (2023), “With or Without Him? Experimental Evidence on Cash Grants and Gender-Sensitive Trainings in Tunisia,” Journal of Development Economics, 165: 103169.

Giuliano, P (2021), "Gender and culture," Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 36: 944–961.

Goldin, C (2014), "A grand gender convergence: Its last chapter," American Economic Review, 104: 1091–1119.

Griffith, A L (2014), “Faculty gender in the college classroom: Does it matter for achievement and major choice?” Southern Economic Journal, 81: 211–231.

Gutierrez, I A, O Molina, and H R Nopo (2018), “Stand against bullying: An experimental school intervention,” IZA Discussion Papers no. 11623.

Halim, D, E Perova, and S Reynolds (2023), "Childcare and mothers’ labor market outcomes in lower-and middle-income countries," The World Bank Research Observer, 38: 73–114.

Hansen, C, P Jensen, and S Volmar (2015), "Modern Gender Roles and Agricultural History: The Neolithic Inheritance," Journal of Economic Growth, 20: 365–404.

Hausemann, R, and M Szekely (2001), “Inequality and the family in Latin America,” in Population Matters: Demographic Change, Economic Growth, and Poverty in the Developing World, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 260–295.

Heath, R (2017), “Fertility at work: Children and women's labor market outcomes in urban Ghana,” Journal of Development Economics, 126: 190–214.

Heath, R, and X Tan (2020), “Intrahousehold Bargaining, Female Autonomy, and Labor Supply: Theory and Evidence from India,” Journal of the European Economic Association, 18: 1928–1968.

Herrera Almanza, C, and D E Sahn (2018), "Early childbearing, school attainment, and cognitive skills: evidence from Madagascar," Demography, 55: 643–668.

Herrera Almanza, C, D E Sahn, and K M Villa (2019), “Teen fertility and female employment outcomes: evidence from Madagascar,” Journal of African Economies, 28: 277–303.

Ho, L, S Jalota, and A Karandikar (2023), “Bringing Work Home: Flexible Arrangements as Gateway Jobs for Women in West Bengal,” Technical Report, MIT Working Paper.

Hojman, A, and F Lopez Boo (2022), "Public childcare benefits children and mothers: Evidence from a nationwide experiment in a developing country," Journal of Public Economics, 212: 104686.