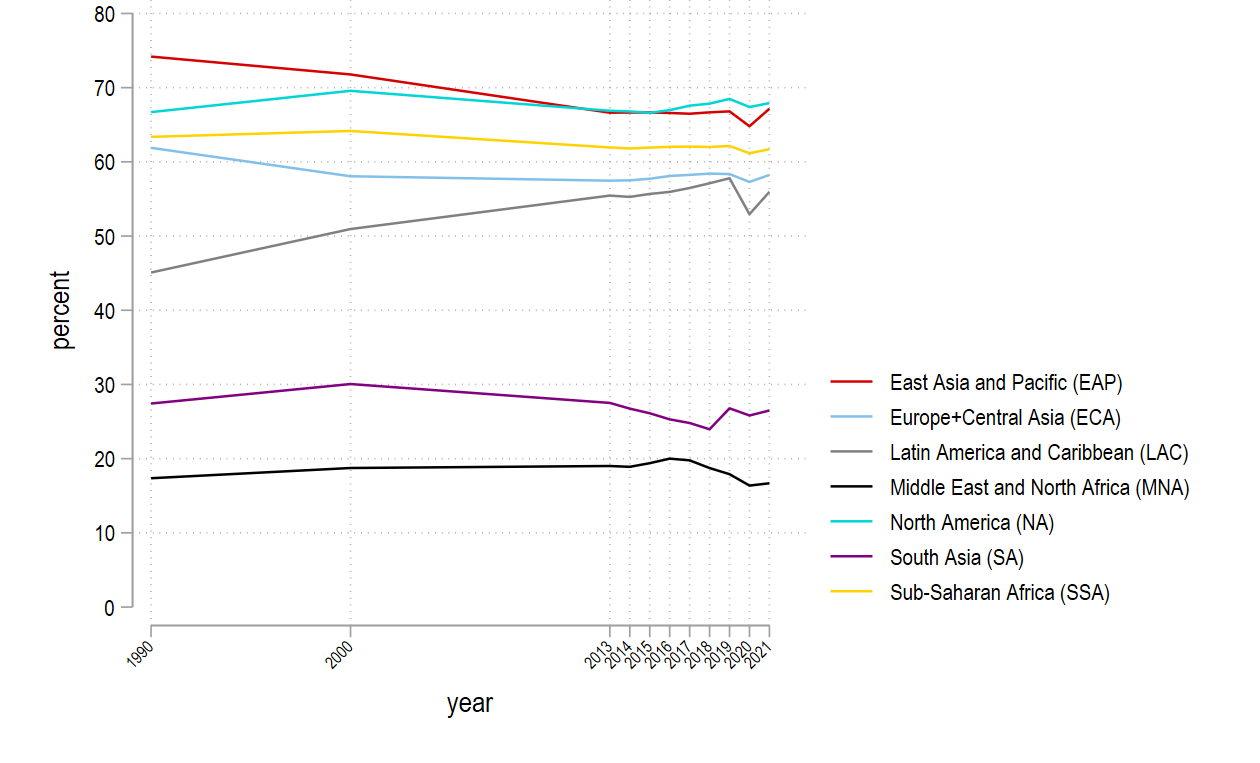

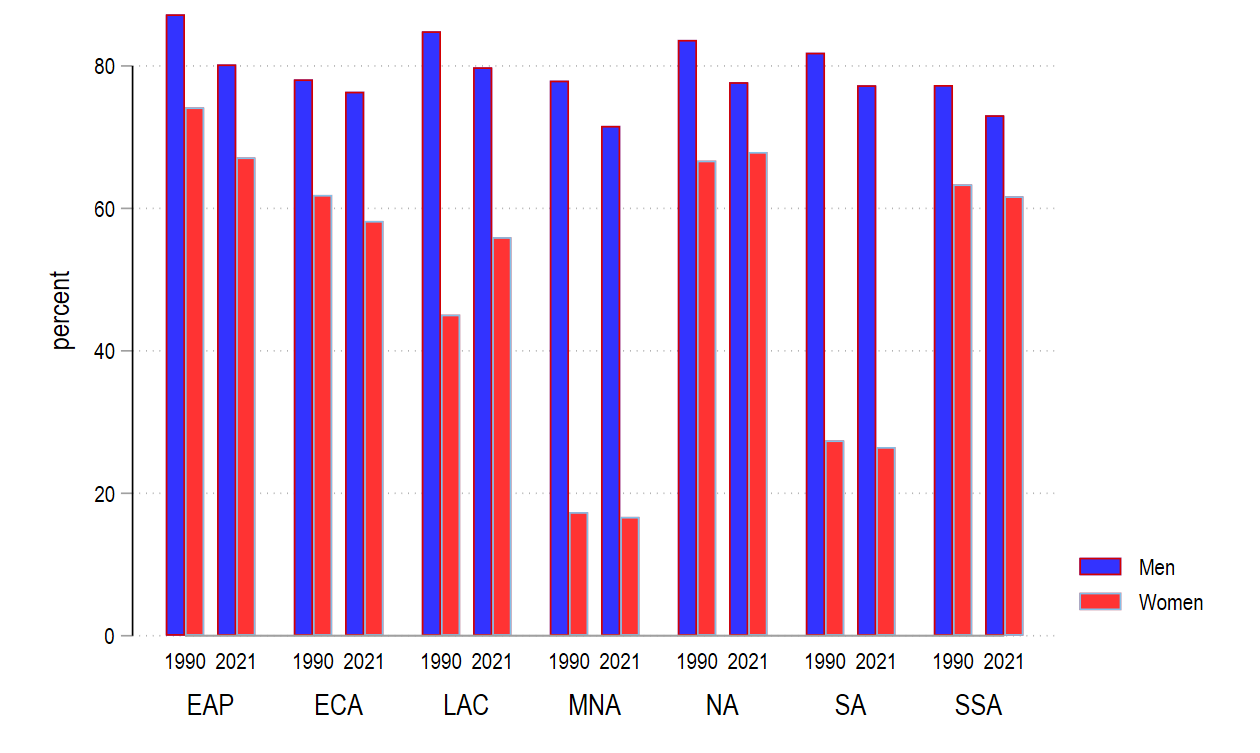

Throughout the world, women’s labour force participation is lower than men’s. But the gap between men’s and women’s labour force participation varies strikingly across regions, which suggests that the gender-specific constraints to labour supply are context specific. For instance, Figure 1 shows that women’s labour force participation in 2021 ranged from 17% in the Middle East and North Africa (vs 72% for men) to 68% in North America (vs 78% for men). Moreover, in most regions of the world, women’s labour force participation has stagnated or fallen over the past 30 years, with Latin America a notable exception.

Figure 1

Panel A: Women’s labour force participation over time

Panel B: Women’s vs men’s labour force participation

Women’s labour supply has important impacts on women’s empowerment (Atkin 2009, Majlesi 2016, Molina and Tanaka 2023) and the human capital of children, especially girls (Qian 2008, Atkin 2009, Heath and Mobarak 2015). Moreover, by contributing to an inefficient distribution of talent, low female labour force participation can be an impediment to overall economic growth (Hsieh et al. 2019, Ashraf et al. 2022, Bandiera et al. 2022). Increasing women’s labour supply is thus a common and important policy goal, both as an outcome in and of itself (e.g. the UN’s 8th Social Development Goal: “Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all”), and due to instrumental reasons such as improving children’s outcomes or achieving gender equality (e.g. the UN’s 5th Social Development Goal: “Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls”).

We accordingly examine the constraints to women’s labour force participation on both the supply side (factors that affect women’s decision to participate in the labour force) and demand side (factors that affect employers’ decision to hire female workers). While we believe this broad distinction is useful, we acknowledge that constraints interact. For instance, a robust empirical finding is that children decrease women’s labour supply on the extensive margin, which we consider a supply-side constraint to women’s labour force participation. However, we also present evidence that prompting employers to provide “female-friendly” amenities like flexibility in work location or the presence of childcare facilities increases retention of women employees with children.

Many of the constraints we identify point to policies that can potentially increase women’s labour force participation by alleviating those same constraints. For example, we cite evidence that harassment on public transportation affects women’s transportation, education, and labour supply decisions. Correspondingly, women-only (or otherwise safe) transportation could increase women’s labour supply and employers’ demand for women workers. However, we also acknowledge that such policies need to be tested in the field to assess whether they have the anticipated impacts on women’s labour supply and assess the extent to which unintended consequences might arise.

Starting with the supply-side, we begin by discussing the role of fertility and childcare. Throughout the world, women spend more time on childcare than men, so there is strong reason to believe that reducing fertility increases labour supply. Some studies indeed find that increased access to contraception increases labour supply, while others do not, highlighting the potential complementarity between such programmes and contextual factors like the sectoral distribution of jobs. The evidence on childcare availability increasing women’s labour supply is more consistently positive, with recent evidence finding that community-provided childcare is a promising mode of delivery.

We then examine the role of intrahousehold constraints, norms, and psychological factors. Within the household, there is evidence that a woman’s bargaining power affects her decision to work. Closely related is the idea that cultural norms - a society’s informal rules about what constitutes appropriate behaviour – affect labour supply. In both cases, increasing men’s support for women’s work can potentially increase women’s labour supply. At the same time, internal considerations matter too; we discuss several recent papers that find that psychological interventions affect women’s labour supply.

Finally, we discuss workplace amenities. Given evidence that women have high demand for flexibility in workplace arrangements (presumably due to care-taking obligations), there is evidence that jobs that provide flexibility or amenities like childcare increase women’s labour supply in the short run, though the longer-run evidence is more mixed, plausibly because women ultimately have difficulty combining even flexible work with home obligations. These “female-friendly” amenities also contribute to gender wage gaps by discouraging female employees from leaving, and thus increasing employers’ monopsony power of them.

We then turn to the demand-side. We start by discussing the potential for discrimination to affect women’s labour force participation. We present evidence from job advertisements and hiring experiments consistent with discrimination in hiring, i.e. the differential treatment of men vs women with the same productivity. There is also evidence that employees respond more negatively to feedback from female supervisors and have biased beliefs about their ability, which suggest that many firms are promoting fewer women than is optimal. However, interventions that provide exposure to, or information about, female leaders can mitigate some of these disparities.

We then examine the role of human capital, looking in particular at education, vocational, and entrepreneurship training. While in some cases, improved skills increase women’s earnings and labour supply, in other circumstances, no effects are found. There is also no consistent pattern of effect sizes between women and men. These mixed effects make sense, given that programmes to increase human capital primarily pay off in the presence of jobs that reward that specific human capital.

Finally, we examine the effects of globalisation on women’s labour force participation. The extent to which increases in globalisation (e.g. by reducing tariffs) increases women’s labour force participation varies depending on the female-intensity of employment in the most affected sectors, but a frequent finding is that, on average, globalisation promotes women’s labour supply. The extent to which globalisation reduces gender pay gaps depends on context-specific factors like the industrial composition and enforcement of anti-discrimination laws.

Overall, the evidence we discuss suggests that women’s labour force participation is affected by both “tangible” constraints such as childcare availability or harassment on transportation to work, and by more “intangible” constraints such as norms against women’s work and psychological barriers. These constraints can be addressed by policies that target women (e.g. by raising their bargaining power), their communities (e.g. by increasing childcare availability), as well as interventions that prompt businesses to address discrimination against women or offer more female-friendly amenities.

References

Aaronson D, R Dehejia, A Jordan, C Pop-Eleches, C Samii and K Schulze (2021), “The effect of fertility on mothers’ labor supply over the last two centuries.” The Economic Journal, 131(633): 1-32.

Ashraf, N, O Bandiera, V Minni, and V Quintas-Martinez (2022), “Gender Roles and the Misallocation of Labour Across Countries,” Working Paper, London School of Economics and Political Science.

Atkin, D (2009), “Working for the future: Female factory work and child health in Mexico.” Unpublished Manuscript, Yale University, 150.

Bandiera, O, I Lindenbaum, C Moser, A Prat, and A Kotia (2022), "Job Diversification and Economic Growth," Technical Report, London School of Economics and Political Science.

Heath, R, and A M Mobarak (2015), “Manufacturing growth and the lives of Bangladeshi women,” Journal of Development Economics, 115: 1–15.

Hsieh, C T, E Hurst, C I Jones, and P J Klenow (2019), “The allocation of talent and US economic growth.” Econometrica, 87(5): 1439-1474.

Majlesi, K (2016), “Labor market opportunities and women's decision making power within households.” Journal of Development Economics, 119: 34-47.

Molina, T, and M Tanaka (2023), "Globalization and female empowerment: Evidence from Myanmar," Economic Development and Cultural Change, 71: 519–565.

Qian, N (2008), “Missing women and the price of tea in China: The effect of sex-specific earnings on sex imbalance.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(3): 1251-1285.

Contact VoxDev

If you have questions, feedback, or would like more information about this article, please feel free to reach out to the VoxDev team. We’re here to help with any inquiries and to provide further insights on our research and content.