Training programmes aimed at microenterprises yield, on average, modest increases in profits and sales. However, there is no evidence that training unlocks rapid and sustained growth of microenterprises. Training appears to be a means of increasing incomes of microenterprises, but not of generating the sort of growth that will propel the aggregate economy. What is the evidence that training and consulting is effective when applied to larger-scale enterprises? The existing evidence for larger firms is much more limited, at least in part because larger firms are fewer in number and training programmes need to be more intense and therefore more expensive. We divide the review into evidence on sector-based programmes designed around the Kaizen model, business consulting, and programmes like incubators and accelerators designed for high-growth start-ups.

Kaizen

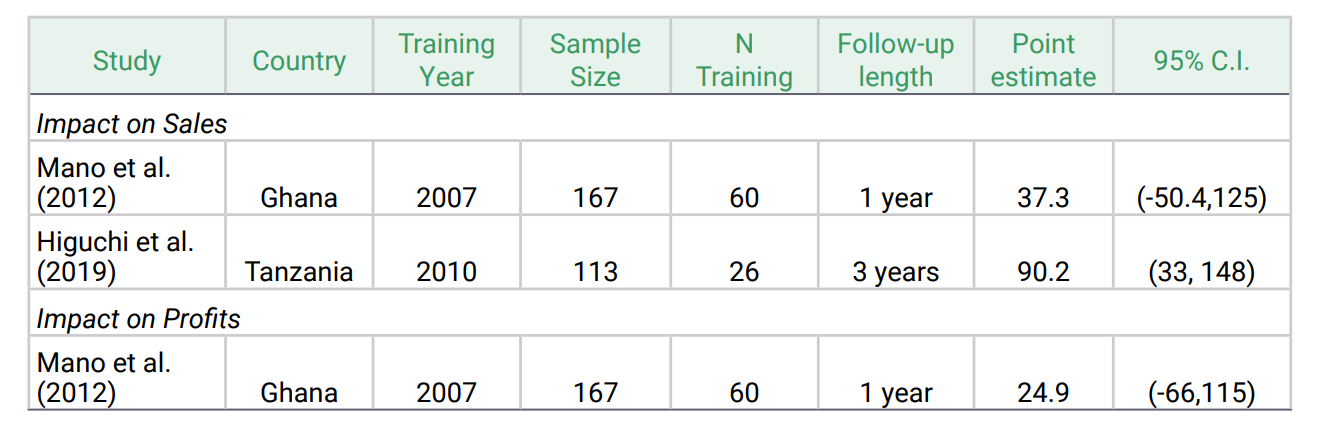

An alternative form of training focuses on production and quality management. There are several randomised evaluations of programmes based on the Japanese-inspired concept of lean production, or kaizen (continuous improvement), delivered to firms organised in industry clusters. This includes visual control examining workflow and bottlenecks, and habit-forming techniques such as 5S, which induce workers to reduce waste, ensure safety first, maintain machinery and equipment, keep the workspace clean and uncluttered, and find remaining problems and suggest solutions. The first experiment to test this approach is Mano et al. (2012), who added a module on this approach to two modules based on the ILO’s standard programme (SIYB). Working with 167 small metalwork firms in Ghana, they find that training increases one-year survival by 8 to 9 percentage points, but effects on profits and sales are imprecisely measured (Table 3).

The kaizen approach has also been evaluated with experiments amongst 316 steel construction and knitwear firms in Vietnam (Higuchi et al. 2015), and 113 garment firms in Tanzania (Higuchi et al. 2019). In both cases, the researchers split the samples into four groups, comparing classroom training only with training on-site, or a combination of the two. The number of firms getting any particular training combination is small – approximately 30 in the Tanzania example. Neither study estimates impacts on profits, but they both show that firms adopt more management practices, and that value-added improves after some time. A longer-term follow-up of the Vietnam sample by Higuchi et al. (2017) finds firms assigned to training were 17 percentage points more likely to still be in business five years after training. The Tanzania study also finds large increases in sales – 90% higher after three years for the group getting both classroom and on-site training (95% C.I.: +33, +148). None of the kaizen studies report impacts on firm employment.

While these results suggest potential in this kaizen approach, studies on much larger sample sizes are needed to feel more confident in the effectiveness. Moreover, it would be good to benchmark kaizen against a standard training programme, to measure how much additional benefit the kaizen content provides.

Table 3: Impacts of kaizen

Other specialised training for SMEs

Apart from this kaizen approach, classroom-based training has seldom been used with small and medium enterprises, except for programmes that aim to train their workers. But other types of specialised training may also have a role in helping SMEs. A first example is MBA-style training for executives. Custódio et al. (2020) test this idea by providing executive education in finance to managers of 93 medium and large firms in Mozambique and find this decreases the amount of working capital held and increases the return on assets. A second example is providing training specifically focused on expanding demand through accessing specialised customers such as governments or overseas buyers. Hjort et al. (2020) provides an example, conducting an experiment with 1,192 firms of average size 14 employees in Liberia, inviting them to a seven-day training on how to bid for large procurement contracts. Take-up is low, with only 20% of firms attending, but they find trained firms win more contracts, with a large, but not statistically significant, impact on revenues from contracts.

Consulting

Business consulting offers a more customised, intensive, and individually tailored approach. A typical consulting intervention begins with a diagnostic that evaluates existing management practices across a range of functional areas such as production, logistics, human resources, and finance, and identifies a set of priority areas for improvement. A consultant or team of consultants then works directly with management and workers of the firm to implement improvements in the firm in a sustained and intensive interaction that can often last for six months or more. Governments supporting the use of consultants often are most interested in the impacts of these programmes on the productivity of firms and on employment, rather than just sales and profitability.

The cost of consulting programmes can vary dramatically depending on the number and type of consultants used, and their intensity. A single local consultant working one-on-one with a small firm for 88 hours costs US$ 4,000 in Nigeria (Anderson and McKenzie 2020) and US$ 12,000 for 200 hours in Mexico (Bruhn et al. 2018). In contrast, a team of local consultants cost US$ 30,000 per firm for 500 hours of consulting in Colombia (Iacovone et al. 2022) and a team of international consultants had a market price of up to US$ 250,000 per firm for 780 hours of working with large firms in India (Bloom et al. 2013). While these numbers are much larger than the cost of training smaller firms, since the firms receiving consulting are much larger and profitable to begin with, a 5% or 10% improvement in profits may still be enough for consulting to pay for itself.

Large firm consulting

A proof of concept that intensive individual consulting can deliver improvements in large firms was shown in an experiment by Bloom et al. (2013) with large textile factories in Mumbai, India. These firms had an average of 270 employees, US$ 7.5 million in sales, and often had more than one plant. A sample of 17 firms (with 28 plants) was split into a treatment group of 11 and a control group of 6. The control firms received a one-month diagnostic, which was deemed necessary both to retain their interest and to ensure the quality and comparability of the information reported. The treated firms received an additional four months of consulting services aimed at improving management practices. Using high-frequency data on output and quality defects, Bloom et al. show that the intensive consulting intervention significantly increases output per worker and TFP, and significantly reduces inventory levels and the quality defect rate. The intervention also led to improvements in management practices. They estimate that the changes resulted in an increase in profits of US$ 325,000 per year per firm, implying that the cost of the consulting, which they estimate as US$ 250,000, is recouped in less than a year. Why did managers not adopt the practices on their own? There are both proximate and deeper answers to this question. Using data that the consultants obtained from managers, Bloom et al. show that the proximate reasons are either that the managers were unaware of the practice (most often for “uncommon” practices), or that they did not think that adopting the practices would be profitable (most often for “common” practices). Bloom et al. (2020) returned 8-9 years after the consulting to see whether the improvements persist, finding that there is a lasting impact on firm practices and a proxy for productivity, but that firms stop using some of the management practices over time, particularly when key managers leave.

Scaling up such an approach is difficult given the expense. Iacovone et al. (2022) test whether consulting can be effective when delivered at a cheaper cost, in an experiment with 159 auto-parts firms in Colombia. They test an individual consulting intervention that is similar to the Indian case, but using local consultants and costing US$ 30,000; and a group-based approach that has a consultant work with groups of 3-8 firms, at a cost of US$ 10,000 per firm. They find that the group-based approach leads to the same improvement in measured management practices as the more expensive individual option, and that it results in increases in employment (6-15 workers), sales (28-33%), and profitability (5-26%) over the subsequent three years. Labour productivity increases by 11-14 percentage points, although this impact is not statistically significant.

Consulting to expand exports

In addition to expanding productivity, policymakers often have a strong interest in increasing the variety and amount of exports. There are two approaches consulting can use to try to achieve this aim. The indirect approach is to first focus on improving general management practices, with the aim that this improves productivity and makes firms better able to compete in international export markets. Iacovone et al. (2023) test such a programme in Colombia, and find that it appears to have actually reduced exports, with firms improving general management practices but not those specifically related to exporting, and in some cases being advised to focus more on domestic sales. The alternative is to provide firms with specific help in learning how to attract customers in overseas markets, meet quality standards for different markets, and overcome logistics constraints that can make it hard to sell in another market. Cusolito et al. (2023) show that a mixture of training and consulting for innovative firms in the Western Balkans was able to expand exports at the intensive margin, enabling those firms who were exporting to sell more by expanding their customer base, learning specific knowledge about how to sell in particular European markets, and getting the confidence to move forward with new ideas.

Consulting for small firms

While the above experiments took place in firms with many workers and several departments, consulting can also potentially offer benefits to smaller firms. A very common form of government support occurs through matching grant programmes, where the government subsidises firms to use consulting services, but requires firms to pay a fraction of the cost. Campos et al. (2014) note that more than US$ 1.2 billion has been spent on World Bank matching grant projects; however, they have been difficult to evaluate.

Bruhn et al. (2018) conduct an experiment with 432 micro, small- and medium-sized firms taking part in a matching grant programme in Puebla, Mexico, with firms paying 10-30% (depending on size) of the US$ 12,000 cost of consulting. Their firms are much smaller than those in the Bloom et al. study, with around 70% classified as “micro” and 22% “small”, and an average of 14 full-time employees. Treated firms received weekly four-hour sessions over a period of one year. The researchers find generally positive but somewhat fragile impacts on profitability and return on assets at the end of the year of consulting. More impressive results come from national Social Security system (IMSS) data for as long as five years after treatment. The IMSS data show that treated firms grew faster than control firms after the programme, leading to 57% higher employment after five years, or 5.7 extra employees per treated firm. However, the IMSS records are available for just over half (57%) of their sample, and are aggregated to total employment for the treatment and control groups. We therefore cannot tell whether the growth comes from a few firms or is spread more widely across the sample. This makes the cost-effectiveness somewhat difficult to assess.

Anderson and McKenzie (2020) evaluate the effects of a government programme that offered firms with two to 15 workers 88 hours of consulting time spread over six to nine months. They find that two years later, consulting had improved a wide range of business practices, and that there were positive, but imprecise, impacts on sales, profits and employment. Anderson et al. (2020) use university students as consultants to visit Mexican small firms in 13 sessions of about three hours each, with the goal of helping firms modernise by improving the appearance and marketing of the store, or by improving their internal financial and stock-keeping methods. They find treated firms improve sales by 15 to 19% over the next 18 months, but do not report impacts on profits or the cost of scaling such an approach.

Markets for training and consulting services

Although Bloom et al. show that the returns to very intensive management consulting are reasonably high, the market for these services has been slow to develop. Many firms appear willing to pay something for training, but demand falls quickly with price and the willingness to pay of most firms is far short of the cost of providing these services (Maffioli et al. 2020).

There are multiple reasons why firms may be reluctant to pay for training or consulting, and why these markets do not work as well as they could. A first set of reasons relates to information frictions. Firms may not know what they do not know, and over-estimate how well-managed they are. For example, Iacovone et al. (2022) find that Colombian firms perceive their management practices to be much better than the reality. Bruhn and Piza (2022) find that giving Brazilian firms concise information about their current level of business practices and where they can obtain help leads to a 7 percentage point increase in the likelihood they use services from SEBRAE, a business service non-profit, in the next few months. Secondly, even if they know they need to improve, the market for consulting services may be opaque, and firms may find it hard to know which providers exist and how good their quality is. Anderson and McKenzie (2021) study the market for business service providers in Nigeria and find that most small firms do not even know of the existence of most of the providers in the market, and that providers largely rely on word-of-mouth for new customers, not doing a lot of advertising. However, giving firms information about the different providers in the market and an external signal of their quality from mystery shoppers was not enough by itself to get more firms to purchase these services.

A second reason then concerns beliefs and uncertainty about the expected returns to using these services, and relates to the issues of external validity and heterogeneity of impacts. Even if the average impact of training or consulting has been shown to be positive and pass a cost-benefit test, firms may be uncertain as to whether using these services will be profitable for their specific business. Indeed, in some cases they may not be. Karlan et al. (2015) found that in an experiment with small tailors in Ghana, taking up the advice of consultants actually lowered profits on average in the short-term, leading them to stop using the recommended practices and revert back to their prior scale of operations. Firms may then rely on recommendations from trusted friends, or require an initial subsidy to learn through experience. Anderson and McKenzie (2020) find that firms who received a subsidy to hire insourcing and outsourcing providers were subsequently more likely to go back to the market and spend their own money to hire more services. Atherton et al. (2002) and Ezell and Atkinson (2011) argue that public support for these services can then in fact be “market-making”, by helping SMEs understand the value of these services and building future demand. Future work is needed to understand what the optimal level of public subsidy is, and whether there is empirical support for this idea that subsidising services can expand overall market demand by demonstration to trusted peers.

However, a final point to note on this is that it may be hard for firms to know whether consulting (or training) has helped them, even after they have received these services. Firm profits and revenues are typically very volatile and driven by a large number of factors that the entrepreneur cannot observe. As we have noted, studies with hundreds of firms often struggle to detect whether the programme is effective, so thinking that an individual firm can simply observe whether consulting has helped it or not may be overly optimistic.

Consulting and training in fragile and conflict-affected states

The World Bank estimates that by 2030, two-thirds of the world’s extreme poor will live in fragile and conflict-affected states. The need to increase incomes for the poor and generate jobs in these environments has meant development agencies are increasingly looking for policies that can work in these environments. However, to date, almost all of the evaluations of training and consulting programmes have taken place in less fragile settings, raising questions as to whether they are applicable in settings where the supply of consultants and trainers may be much more limited, and firms facing considerable uncertainty about the continued viability of their businesses. Conducting research in these settings is difficult, and there is not yet a body of research to synthesise, but a couple of evaluations of consulting services do suggest firms receiving consulting are better able to survive and innovate in these settings. Pulido (2021) reports on an experiment with 190 SMEs in Venezuela, where half were given individualised consulting over nine months. They find the programme helped firms with ten or more workers to survive, but smaller firms had higher drop-out and no survival impact. McKenzie et al. (2017) conducted an experiment with 416 firms in Yemen in the run-up to the civil war, where treated firms received matching grants to purchase consulting services for accounting, marketing and training. They find, in the first year, treated firms are 30 percentage points more likely to innovate by introducing a new product, implement more marketing and accounting practices, and are more likely to report sales growth. However, longer term follow-up was not possible due to the outbreak of civil war.

Incubators and accelerators for high growth start-ups

High-growth potential start-ups are of particular interest to many policymakers, because of their potential for innovation and rapid growth, and because of their relative scarcity in developing countries (Eslava et al. 2019). Most of these firms are young and have few workers, but they differ from micro and small firms in terms of the types of entrepreneurs running these firms, and in the technologies and industries. Entrepreneurs starting these types of firms are often highly educated and highly motivated. The result is that these entrepreneurs are less likely to need training on basic business skills or on cultivating an entrepreneurial mind-set, but instead need more specialised assistance with their business model, and with positioning their firm to receive outside financing from investors. The most common intensive approach is to support firms through business accelerators and incubators. Accelerators often offer firms some seed capital, workspace and other “non-monetary services” (such as mentoring and opportunities to network), in addition to training. These programmes typically work with small cohorts of 10 or 20 firms at a time, and last three to six months on average, although participants often remain connected through alumni networks.

A typical accelerator programme starts with a rigorous selection of entrepreneurs into a cohort that receives training and mentoring from successful business owners either from within the country or remotely. Many accelerator programmes provide links to angel finance or provide grants to enterprises completing the training. The combination of selection and the provision of a bundle of services makes the effect of accelerators particularly difficult to measure. There are a limited number of studies that use a credible comparison sample.

The most credible evaluations of accelerators to date use characteristics of the selection processes in these programmes as a source of exogenous variation in participation. The first such exercise is by Gonzalez-Uribe and Leatherbee (2017), who use a regression discontinuity design (RDD) to explore the effects of StartUp Chile, an accelerator that offers participants cash, workspace, and the possibility of being selected into the “entrepreneurship school” where additional non-monetary services are provided. With 1000 ventures selected to participate in the programme from amongst 6000 applicants, the marginally selected applicants are reasonably similar to the marginally rejected applicants. All applicants also receive a quantitative score, which can be used as a control for differences in enterprise potential.

Gonzalez-Uribe and Leatherbee show that ventures selected to participate in the Startup Chile programme (compared to those not selected) are more likely to: raise subsequent finance, survive, and have a web presence. However, the analysis shows that these effects are entirely driven by selection of higher-quality ventures into the programme. The basic accelerator programme – the office space and capital grant – has no additional effect on these outcomes.

There has been much less analysis of the specific components of accelerator programmes. One first attempt was made by Gonzalez-Uribe and Leatherbee, who assessed the impact of an “entrepreneurship school” that is offered to 20% of Startup Chile participants. The school is additional to the basic programme, providing monthly meetings with programme staff, peers, and industry experts; opportunities for networking; and advertisement on the programme’s web page. Exploiting the discontinuity in acceptance into the additional programme, they find that the schooling, bundled with cash and other basic services, significantly improves the performance of ventures, even after controlling for selection effects. Within five years, entrepreneurs receiving the additional training see a 21% (0.29 standard deviation) increase in the probability of securing additional financing, triple the amount of capital raised (from $37K to $112K; a 0.30-standard-deviation increase), and double the number of employees (from 0.9 employees to 1.8, a 0.34 standard deviation increase).

While the evidence in Gonzalez-Uribe and Leatherbee (2017) shows that the non-monetary services provided by accelerators can affect performance when bundled with cash grants, it raises the question of whether non-monetary services on their own can have meaningful impacts. Gonzalez-Uribe and Reyes (2021) tackle this question in the context of ValleE, a business accelerator in Colombia, that instead of providing cash to participants, offers standardised business training, customised business advice, and visibility. For identification, they exploit variance in the generosity of the randomly assigned panellists charged with selecting enterprises into the programme. A key advantage of the setting is the administrative revenue data from the Colombian business registry two years before application and three years after.

Gonzalez-Uribe and Reyes show that the provision of non-monetary services on their own, significantly increases average annual revenue by 166% relative to rejected applicants. The average effect masks substantial heterogeneity: whereas firms with the highest growth potential at application exhibit remarkable growth, there is no evidence that the programme increases growth for the participants with the lowest potential. This result is consistent with the emphasis of these programmes on rigorous selection processes.

More work is needed to further unpack the components of incubator and accelerator programmes to identify the non-monetary services that have the highest impact and are most cost-effective and scalable. The evidence on this topic remains mostly informal, but points towards the importance of services different from standard business training. An exception is a recent work by Assenova (2020) distinguishing the effects of mentoring from other services provided to participants in an incubator in South Africa serving socially and educationally disadvantaged entrepreneurs from low-income backgrounds. For identification, she uses seven cohorts of randomly assigned participants to mentors of varying ability during incubation. The findings show that participants assigned to high-ability (versus low-ability) mentors had 3.2% higher revenue and 3.5% higher profits one year after incubation. This growth was highest for businesses whose entrepreneurs had less pre-entry knowledge and experience.

Cusolito et al. (2021) conducted a five-country randomised experiment in Croatia, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, and Serbia, to test the effectiveness of an investment-readiness programme with 346 firms. The components of the programme are similar to the more common accelerator programmes. The firms included in the Cusolito et al. programme had an average of six employees, and were in high-tech innovative industries such as cloud computing and app development. The treatment group received help developing their financial plans, product pitch, market strategy, and willingness to take equity financing, along with master classes, mentoring, and other assistance. Both groups then competed in a pitch competition, and were tracked for two years to measure impacts on receiving outside investments. Treated firms scored higher on their pitch. The programme’s effects were strongest for firms that were smaller and less likely to otherwise get external financing: the programme had a statistically significant 15 percentage point increase in the likelihood of getting external financing for firms below the median size.

References

Anderson, S and D McKenzie (2020), “Improving Business Practices and the Boundary of the Entrepreneur: A Randomized Experiment Comparing Training, Consulting, Insourcing and Outsourcing”, Journal of Political Economy, 130(1): 157-209.

Anderson, S and D McKenzie (2021), “What prevents more small firms from using professional business services? An information and quality ratings experiment”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper no. 9614.

Anderson, S, L Iacovone, S Kankanhalli and S Narayanan (2020) “Modernizing retailers in emerging markets: investigating externally-focused and internally-focused approaches”, Mimeo. UT Austin.

Assenova, V (2020), “Early-Stage Venture Incubation and Mentoring Promote Learning, Scaling, and Profitability Among Disadvantaged Entrepreneurs”, Organization Science, 31(6): 1560-1578.

Atherton, A, T Philpott and L Sear (2002), “A Study of Business Support Services and Market Failure”, European Commission, Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/content/business-support-services-and-market-failure-0_nn [accessed 9 June, 2021].

Bloom N, B Eifert, A Mahajan, D McKenzie and J Roberts (2013), “Does management matter? Evidence from India”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(1): 1-51.

Bloom N, B Eifert, A Mahajan, D McKenzie and J Roberts (2020), “Do Management Interventions Last? Evidence from India”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 12(2): 198-219.

Bruhn M, D Karlan and A Schoar (2018), “The impact of consulting services on small and medium enterprises: Evidence from a randomized trial in Mexico”, Journal of Political Economy, 126(2): 635-687.

Bruhn, M and C Piza (2022), “Missing information: Why don’t more firms seek out business advice?”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper no. 10183.

Campos, F, A Coville, A Fernandes, M Goldstein and D McKenzie (2014), “Learning from the experiments that never happened: lessons from trying to conduct randomized evaluations of matching grant programs in Africa”, Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 33: 4-24.

Cusolito, A, O Darova, and D McKenzie (2023), “Capacity building as a route to export market expansion: a six-country experiment in the Western Balkans”, Journal of International Economics, 144: 103794.

Cusolito, A, E Dautovic and D McKenzie (2021), “Can Government Intervention make firms more investment-ready? A randomized experiment in the Western Balkans”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 103(3): 428-42.

Custódio, C, D Mendes and D Metzger (2020), “The impact of financial education of executives on financial practices of medium and large enterprises”, Mimeo. Imperial College London.

Eslava, M, J Haltiwanger and A Pinzon (2019), “Job creation in Colombia vs the U.S.: ‘up or out dynamics’ meets ‘the life cycle of plants’”, NBER Working Paper 25550.

Ezell, S and R Atkinson (2011), “International Benchmarking of Countries’ Policies and Programs Supporting SME Manufacturers”, The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, September.

Gonzalez-Uribe, J and M Leatherbee (2017), “The Effects of Business Accelerators on Venture Performance: Evidence from Start-Up Chile”, The Review of Financial Studies, 31(4): 1566-1603.

Gonzalez-Uribe, J and S Reyes (2021), “Identifying and Boosting 'Gazelles': Evidence from Business Accelerators”, The Journal of Financial Economics, 139(1): 260-287.

Higuchi, Y, V H Nam and T Sonobe (2015), “Sustained impacts of Kaizen training”, Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 120(C): 189-206.

Higuchi, Y, V H Nam and T Sonobe (2017), “Management practices, product upgrading, and enterprise survival: Evidence from randomized experiments and repeated surveys in Vietnam”, Mimeo. Nagoya City University.

Higuchi, Y, E P Mhede and T Sonobe (2019), “Short- and Medium-Run Impacts of Management Training: an Experiment in Tanzania”, World Development, 114(C): 220-36.

Hjort, J, V Iyer, and G de Rochambeau (2020), “Informational barriers to market access: Experimental evidence from Liberian firms”, NBER Working Paper no. 27662.

Iacovone, L, W Maloney and D McKenzie (2020), “Improving Management with Individual and Group-Based Consulting: Results from a Randomized Experiment in Colombia”, Review of Economic Studies, 89(1): 346-371.

Iacovone, L, D McKenzie and R Meager (2023), “Bayesian Impact Evaluation with Informative Priors: An Application to a Colombian Management and Export Improvement Program”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper no. 10274.

Karlan, D, R Knight, and C Udry (2015), “Consulting and Capital Experiments with Microenterprise Tailors in Ghana”, Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 118: 281-302.

Maffioli, A, D McKenzie and D Ubfal (2020), “Estimating the Demand for Business Training: Evidence from Jamaica”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 9415.

Mano, Y, A Iddrisu, Y Yoshino and T Sonobe (2012), “How Can Micro and Small Enterprises in Sub-Saharan Africa Become More Productive? The Impacts of Experimental Basic Managerial Training”, World Development, 40(3): 458–68.

McKenzie, D, N Assaf and A Cusolito (2017), “The additionality impact of a matching grant programme for small firms: experimental evidence from Yemen”, Journal of Development Effectiveness, 9(1).

Pulido, J (2021), “The power of the right advice for small and medium business growth in a difficult political and economic context”, https://www.innovationgrowthlab.org/blog/power-right-advice-small-and-medium-business-growth-difficult-political-and-economic-context.

Contact VoxDev

If you have questions, feedback, or would like more information about this article, please feel free to reach out to the VoxDev team. We’re here to help with any inquiries and to provide further insights on our research and content.