The vast majority of firms in developing countries are microenterprises, with the modal firm consisting of a self-employed individual with no paid workers. These microenterprises are an important source of income for many poor households. The most prevalent forms of business training aim to help potential entrepreneurs start firms, and to help those already running these firms earn more income. Traditional training programmes aim to do this by teaching a wide range of business practices. A second approach attempts to simplify training by teaching a few heuristics and rule-of-thumb. Alternatively, rather than attempting to teach firm owners how to carry out specific practices, it may be more effective to change their aspirations and mind-set. Personal initiative training has shown some promise in improving performance through creating a more proactive mind-set. Finally, training programmes may offer a mixture of skill-based and attitude-based content, as well as tailored content for targeted groups such as women and youth.

Traditional small-business training

Classroom-based training in basic business practices is the most common approach to training small-scale entrepreneurs. The ILO’s Start and Improve Your Business programme, and Freedom From Hunger’s programmes for microfinance clients are examples of the best known and most widely implemented classroom-based training programmes. Although there is a wide variety of classroom business training programmes and approaches, a typical programme involves a trainer teaching a group of 15-to-40 participants over a period of 3-to-12 days. Courses for potential entrepreneurs looking to start a business focus on topics like generating a business idea, developing a business plan, permits, costing, pricing, and budgeting. Courses for owners of existing firms looking to grow, cover record-keeping and accounting, marketing, human resources and hiring workers, stock control and inventory management, planning, and operations management.

Most of these training programmes reach scale by training a set of master trainers, who in turn train a network of trainers in different countries. The course materials are typically translated and adapted to local contexts. While courses are typically traditional teacher-led, classroom-based training, many also incorporate active learning. Participants take part in exercises or games to gain an understanding of key concepts, and complete assignments between training sessions that apply the content to their own businesses. Van Lieshout and Mehtha (2017) report costs for offering a 5-7 day SIYB course in 18 different countries. The costs range from US$400 to US$12,242 for a class of 20, with an average cost of US$3,537, or US$177 per participant. In many countries, and most randomised experiments, training is offered to firms for free or for a token cost – van Lieshout and Mehtha (2017) report a median contribution by participants of 10% of the cost. This large variability in costs reflects differences in whether instructors are specialist trainers or NGO staff, whether venues need to be hired or classes can be held in schools or halls without charge, in transport costs for getting instructors to remote areas, and in the scale of training offered.

As the most prevalent form of business training, traditional classroom training has been subject to the largest number of evaluations. The first such randomised experiment was undertaken by Karlan and Valdivia (2011), who evaluated the impact of training offered to clients of a microfinance institution in Peru. A large sample of over 4,500 borrowers were randomly allocated at the village bank level to a control group, or to a treatment group that received up to 22 weekly training sessions of 30-60 minutes each. The results are also typical of much of the early literature: the authors find significant improvements in some measures of business practices and business knowledge, but no significant impact on business revenue (and they do not measure business profits).

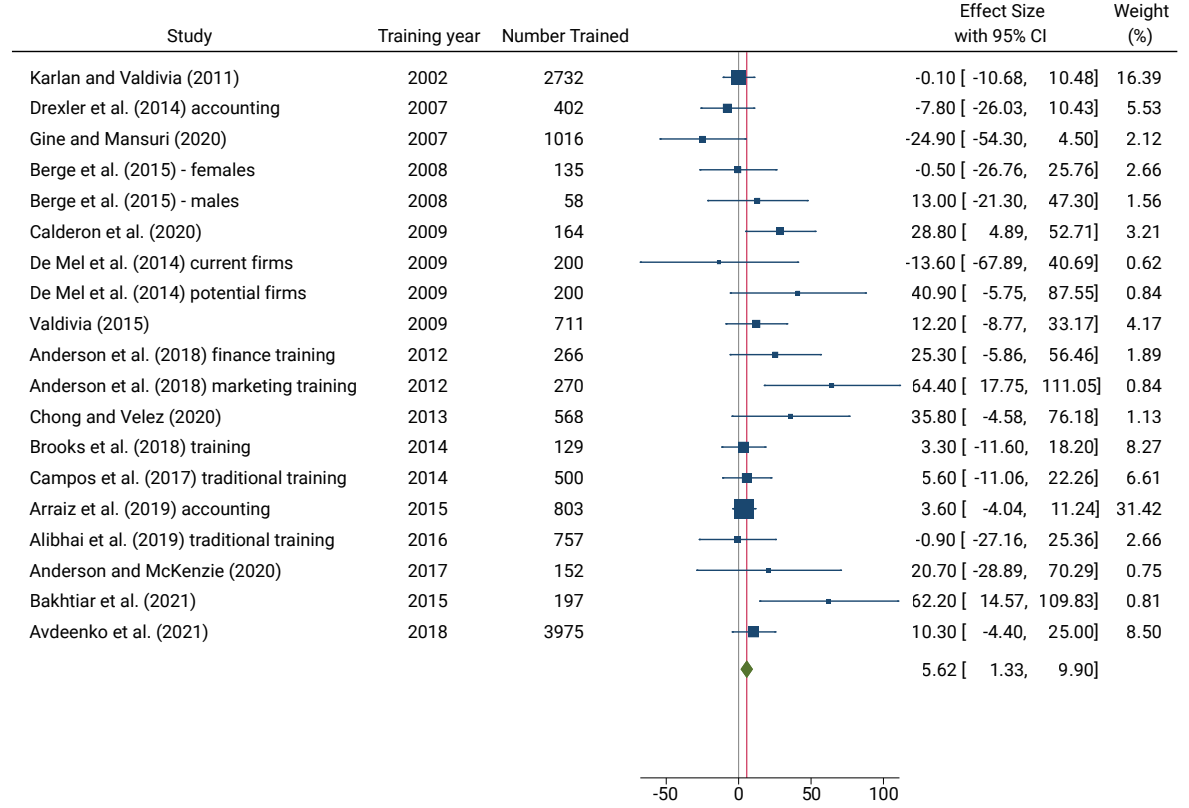

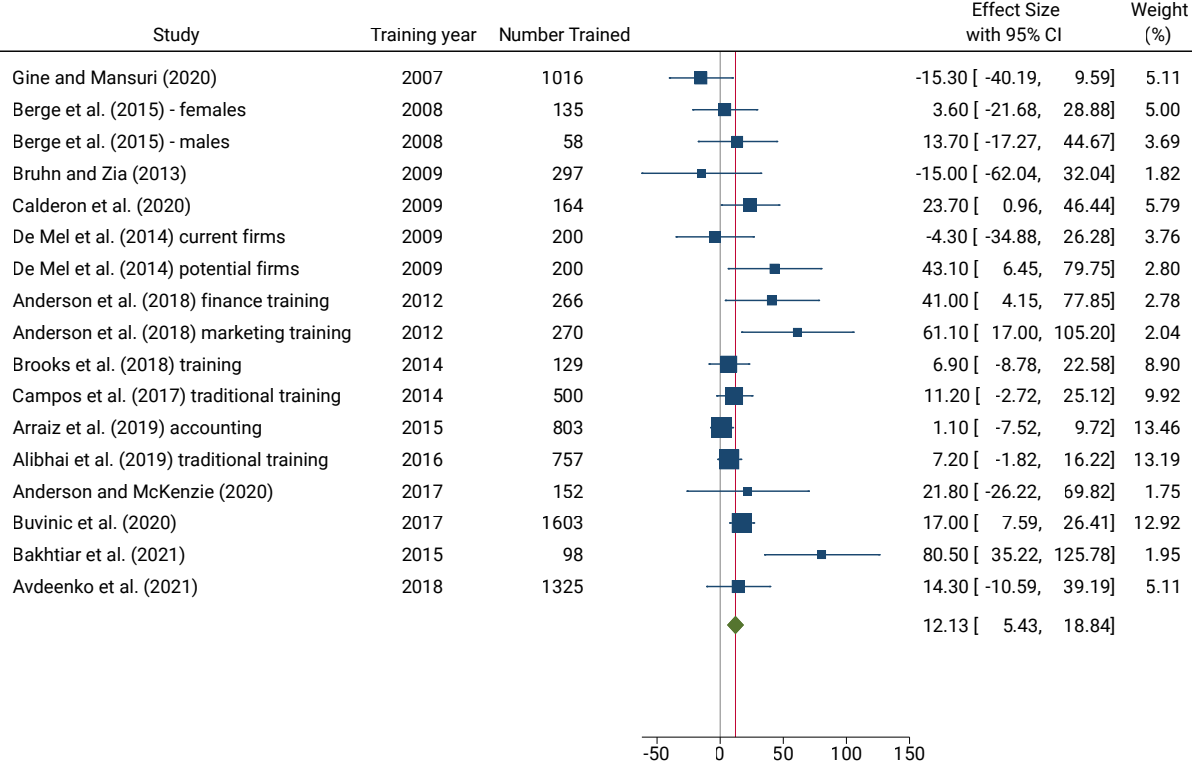

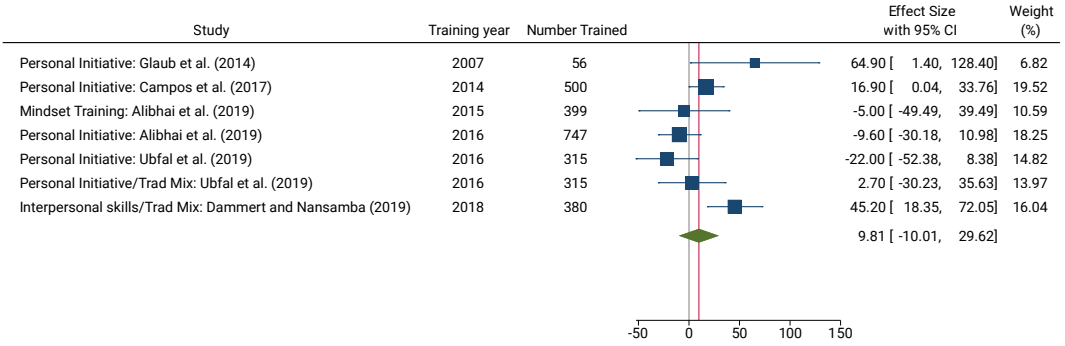

Many of the subsequent studies have also tested variants of traditional training. Figures 1 and 2 summarise the effects on sales and profits, respectively, from these different studies. When considered separately, we see that the confidence intervals of the impact of training in many of these studies are large and include zero. McKenzie (2021) estimates a random effects meta-analysis, and found that the training has a significant positive average effect on both profits and sales, with an estimated 4.7% improvement in sales and 10.1% improvement in profits. We have updated these figures to include new studies released since then, with the average effects now an estimated 5.6% improvement in sales and 12.1% improvement in profits. McKenzie argues that improvements of this magnitude are in line with what is reasonable to expect given what we know about the returns to other forms of education and the return to capital, but that most studies do not have sufficient statistical power to detect effects of these magnitudes. Note that for a firm earning US$100 a month, a 10% increase in profits would therefore enable the typical cost of US$177 of a training course to be recouped within 18 months.

Figure 1: Estimates of the impact of business training on firm sales

Notes: Random-effects REML Model. Source: Original version McKenzie (2021), updated to include new studies

Figure 2: Estimates of the impact of business training on firm profits

Notes: Random-effects REML Model. Source: Original version McKenzie (2021), updated to include new studies

Why doesn’t traditional training have a larger effect? McKenzie and Woodruff (2013, 2017) show that the modest effects on sales and profits are reflected in the fact that enterprise owners implement very few additional best practices after participating in training sessions. A typical SIYB training programme may attempt to teach owners 20 or 30 business practices; however, on average, participants end up improving only one or two of these practices. In part, this reflects the short nature of the courses, but it may also reflect the quality of the training programme and the selection of participants for the course. Training programmes that are more intensive, and those with screening that results in more selective entry into the programme, have shown both larger effects on business practices (e.g. Anderson et al. 2018) and larger effects of the training on enterprise performance. Further work is needed to both measure the quality of training delivery, and to test different approaches to improving the effectiveness of this delivery.

Heuristics and rule-of-thumb

Standard training programmes teach a broad range of practices in a short period of time. They may provide more information than subsistence enterprises can or care to absorb. An alternative is to provide simpler training that focuses on heuristic guidelines or rule-of-thumb. For example, rather than trying to teach detailed accounting practices and how to calculate firm profits, rule-of-thumb training focuses on keeping household and business finances by giving a physical rule to keep money in two separate drawers, and only transfer money from one to the other with an explicit “IOU” note between the business and the household.

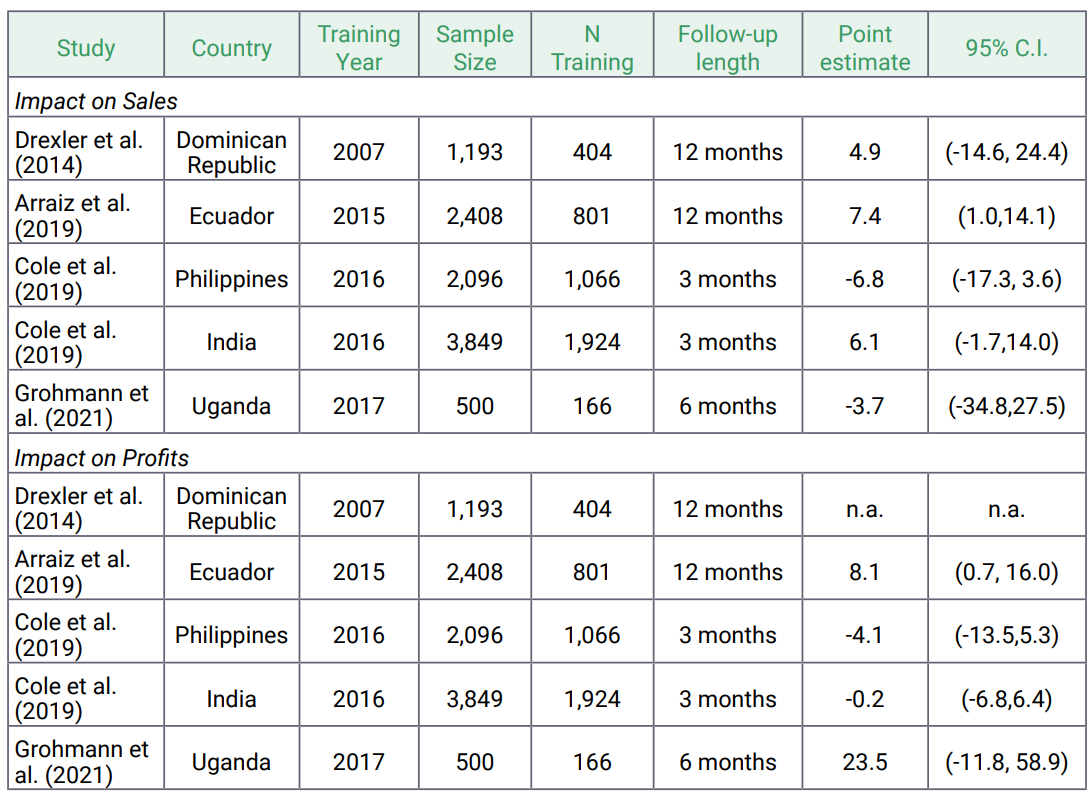

Drexler et al. (2014) evaluate such a training programme in an experiment with 1,193 microenterprises in the Dominican Republic. They find that the heuristic training worked better than more standard accounting training for lower-educated firm owners, but were unable to reject equality of impacts of the two types of training for the full sample (mean effect +4.9%, 95% C.I.: -14.6, +24.4). Statistical power is reduced because sales data are missing for almost half the sample. Somewhat stronger evidence comes from Arráiz et al. (2019), who evaluated a 4-hour rule-of-thumb training for finance amongst 2,408 microenterprises in Ecuador, comparing it with an accounting and finance training programme. Follow-up a year later shows that the heuristic-based approach increased daily profits by 8.1% (95% C.I.: +0.7, +16.0), and daily sales by a similar amount. The rule-of-thumb training was particularly effective for women and those with lower cognitive scores. However, Cole et al. (2019) find limited impacts of sending rule-of-thumb voice messages to small firms in India and the Philippines. Batista et al. (2021) find that a 4-hour rule-of-thumb based training for entrepreneurs in Mozambique has positive, but statistically insignificant impacts at 1 and 5 years, whereas combining it with access to mobile savings accounts results in larger impacts.

Table 1: Impacts of rule-of-thumb training

Note: Batista et al. (2021) not shown since the control mean of profits in their study is negative, making calculation of percent growth on the control mean problematic.

The idea of providing simplified rules that business owners can use offers an appeal for helping the smallest businesses and least-educated entrepreneurs to run their subsistence enterprises slightly better. However, it is unclear from existing studies whether these approaches have long-lasting effects, or whether firms stop using heuristics over time (existing studies only follow firms for a year at most). Moreover, to date, there are limited examples of the types of rule-of-thumb that can be used, largely limited to financing, and it is less clear whether there are relevant heuristics for marketing, stock control, and other important areas of the business.

Teaching an entrepreneurial mind-set

Classroom training programmes typically focus on improving technical business skills in record-keeping, marketing, etc. An alternative approach instead targets attitudes, particularly mind-set and aspirations. Borrowing heavily from psychology, personal initiative training programmes have been the subject of several evaluations in recent years, showing some promise. Personal initiative training aims to develop a proactive entrepreneurial mind-set, encouraging owners to search continuously for new opportunities, learn from errors, and think of ways to differentiate their business from others. For example, a training exercise involves entrepreneurs thinking through their previous business day, and asking what they can do so that tomorrow is an improvement over yesterday.

Campos et al. (2017) carried out an experiment with 1,500 microenterprise owners in Togo, testing the impact of personal initiative training compared to both a control group, and to a group that received the Business Edge programme, a traditional small business training approach. Both groups received 36 hours of classroom training, followed by a trainer visiting each business for one three-hour visit per month for each of the next four months. Personal initiative training is found to improve business profits by 30% over the next two and a half years, which is significantly higher than the 11% increase from traditional training. The result is that the US$750 cost-per-participant of training is recouped with increased profits in less than one year.

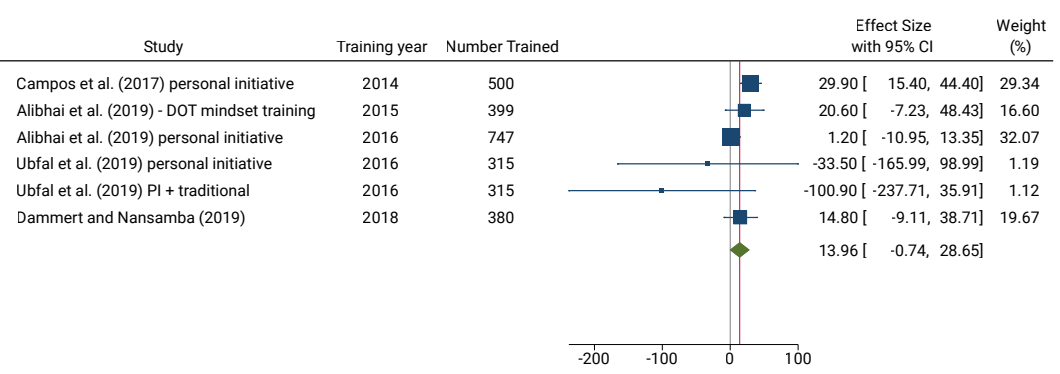

Personal initiative training has been tested in several other countries, including an initial pilot by Glaub et al. (2014) in Uganda, and in studies by Alibhai et al. (2019) in Ethiopia and Ubfal et al. (2019) in Jamaica. There have also been tests of other psychology-influenced training curricula, including interpersonal skills (Dammert and Nansamba 2019) and another form of mind-set training (Alibhai et al. 2019). Figures 3 and 4 summarise the results, and provide a meta-analysis of this emerging set of studies. The average impacts on profits and sales are 14% and 10% improvements respectively, but we see considerable heterogeneity in the impacts across different studies.

Figure 3: Estimates of the impact of psychological training on firm profits

Notes: Random-effects REML Model.

Figure 4: Estimates of the impact of psychological training on firm sales

Notes: Random-effects REML Model.

While there is a lot of interest from different organisations in trying these psychological approaches, there are still many open questions about how to best implement this form of training. Efforts to follow up on the Campos et al. (2017) Togo study found less promising results in Ethiopia and Jamaica. One potential explanation lies in the quality of the trainers and intensity of treatment being lower. A second issue that needs further research is the role of follow-up one-on-one visits after training, which were used in Togo. Some programmes attempt to combine modules on both traditional training topics with modules on personal initiative, and it is unclear whether attempting to do both approaches complements or weakens the emphasis on mind-set in personal initiative training. Finally, it is unclear what the upper limit on firm size or baseline entrepreneurial attitudes should be for participants in these programmes – such training may be less effective for entrepreneurs who already have strong aspirations and who are proactive to begin with.

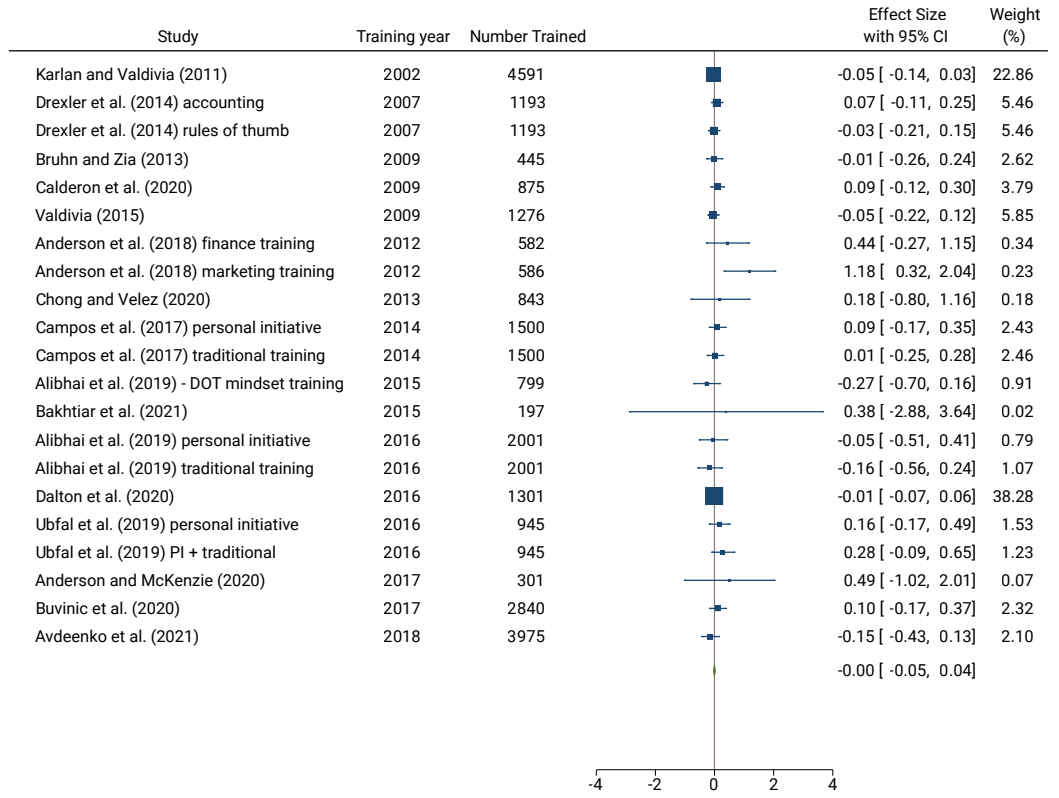

Training impacts on employment

Employment is an important concern for most policymakers, and government subsidies for training are sometimes in part motivated by the belief that it will not only help the person being trained, but also help create jobs for others. However, the typical microenterprise taking part in business training has no or only one additional worker apart from the owner. We have seen firm profits increase by a modest amount of around 10-12%, which equates to only $5-10 a month for a firm earning $50-100 a month in profits. It is therefore hard to see this average gain in profits being sufficient to support the firm taking on another employee. To examine this, we have collected the employment impacts of both traditional and alternative approaches to business training in Figure 5, and run a meta-analysis of the average effect. We see that the treatment impacts are almost always small in magnitude, and statistically insignificant, and the meta-analysis average effect is a very precise 0, with a 95% confidence interval of (-0.05, +0.04) workers.

Figure 5: Estimates of the impact of business training on employment

Notes: Random-effects REML Model. Effect sizes are expressed in terms of jobs created per firm assigned to training.

The main employment impacts of business training for microenterprises are instead likely to be on employment for the firm owner, who may be more likely to start a new business, and to have that business to survive after taking part in training (McKenzie and Woodruff 2013). But training microenterprises does not seem to create more jobs for others, at least over the 1-2 year time horizons of most evaluations.

Training for women and youth specifically

The different training approaches discussed above are designed to apply to a wide variety of microenterprises. However, specific groups of entrepreneurs may face additional constraints, or need additional tailored content.

Programmes for female entrepreneurs

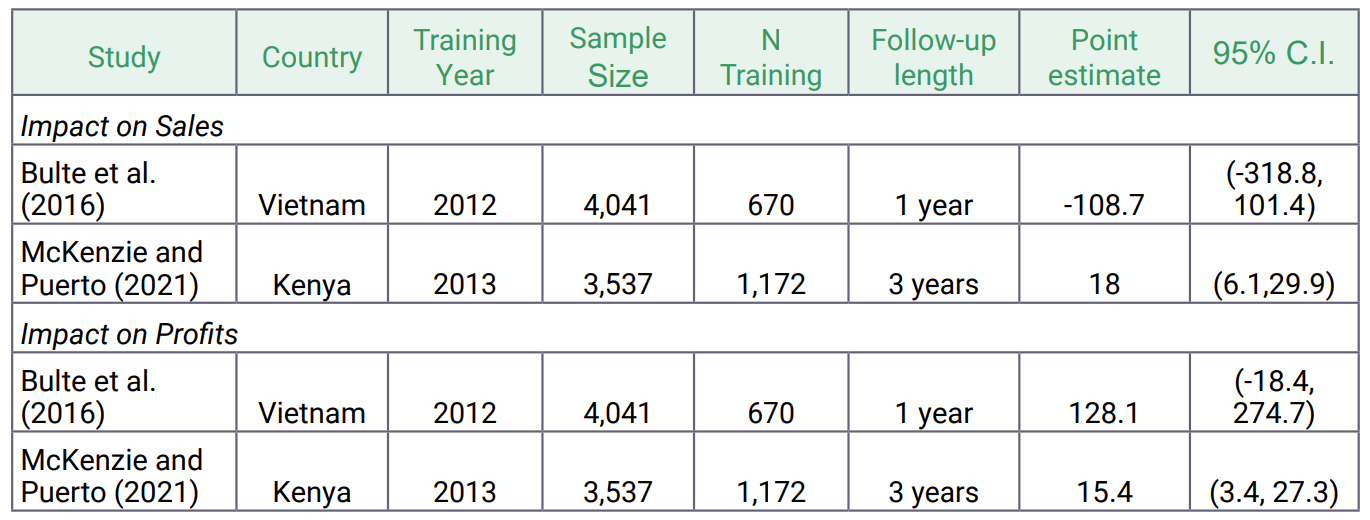

Training programmes designed specifically for female entrepreneurs may aim to also help them overcome additional gender barriers to firm growth, by helping them enter into different sectors, or by teaching them how to better manage segregating household and business tasks, overcoming stereotypes, and working with other women. An example of such a programme is the ILO’s Gender and Enterprise Together (GET Ahead) programme, which combines standard topics like recordkeeping, separating business and household finances, costing and pricing, etc., with topics on gender. This programme has been evaluated in two randomised experiments in Vietnam (Bulte et al. 2016) and Kenya (McKenzie and Puerto 2021). While the programme improved business practices in both cases, only the Kenya study found significant improvements in profits and sales after three years (Table 2). Using a market-level randomisation, McKenzie and Puerto (2021) show that this growth does not appear to have just come from taking away sales from untrained women, but rather, the trained women introduced new products and total market sales grew.

Table 2: Impacts of female-specific training

However, it is unclear how much the extra gender content helped, compared to just the traditional business skills being taught. McKenzie and Puerto (2020) report that they do not see significant impacts on gender attitudes, self-efficacy, or working together with other women, and associated qualitative work does not find women reporting the gender component as especially useful. It would be useful in future work to compare the effects of a programme like GET Ahead to a standard business training programme like SIYB.

Programmes for youth

Youth are another common target group for business training programmes. There are at least three variants of youth business training programmes offered. The first consists of training for out-of-school youth, with the goal of getting them to start businesses or expand existing businesses. In a number of cases, this training is coupled with other forms of assistance such as small grants, making it sometimes hard to assess the impact of training alone. Calderone et al. (2022) provide an example in Tanzania, where rural youth aged 23 on average were given three months of twice a week classroom training on soft skills and business idea and business plan generation, followed by nine months of aftercare. The programme, called STRYDE 2.0, has been implemented at significant scale, reaching over 53,000 youth in four African countries. After two years they find a 2.4 percentage point increase in the likelihood of employment and no significant impact on earnings for the full population, with impacts larger for women: the training cost $418 per head, and their estimates of earnings increases for those who took up training are $3 a month for the pooled sample, or $26 per month for women alone. Brudevold-Newman et al. (2023) compare the impact of a microfranchising programme targeting female youth in urban Kenya with a cash grant programme and pure control. The microfranchising programme bundles training on both technical and business skills with an in-kind grant of the assets needed to establish the business and post-entry mentoring. They find that the microfranchising training increases self-employment rates by about 10 percentage points, an effect sustained for the six years of post-intervention data. But while income increases in the short run relative to the pure control group, the income effect is not sustained after six years.

A second case consists of entrepreneurship education taught in secondary schools, such as the Educate! programme. These programmes typically consist of a combination of soft skills training and business concepts. A challenge in measuring the impact of these programmes is that the impacts may not be seen for several years, until youth have finished school. For example, Chioda et al. (2023) evaluate the Educate! programme that is taught to students in the final two years of secondary school in Uganda and which has an emphasis on entrepreneurship. They conduct a follow-up survey four years later and find that 36% of the sample are still enrolled in tertiary education, leading them to conclude that even four years is too soon to examine labour market outcomes. Chioda et al. (2021) conducted an experiment with 4,400 youth in their final year of secondary school in Uganda (average age 20), and gave them a different three week intensive course that combined hard skills (teaching business practices) and soft skills. They find that 3.5 years later the youth are 6 percentage points more likely to be self-employed, and have 30% higher earnings from all labour market activities, with this increase largely driven by more self-employment income. Berge et al. (2022) conduct an experiment with final year secondary school students in 80 schools in Tanzania, offering economic empowerment and entrepreneurship training that runs for 1.5-2 hours per week for eight weeks. Three to four years later, they find 29% of the control group to be self-employed, compared to 38% of the treatment group, and total work income is about 80% higher relative to a low base of around $11 per month in the control group. Bruhn et al. (2022) examine the long-run effects of a financial education programme for public high school students in Brazil that was piloted in an experiment with 892 schools. The programme included modules on work and entrepreneurship, equivalent to 14-28 hours of material integrated into the regular school curriculum during one semester. Nine years later, treatment students were 10% more likely to own a formal microenterprise, compared to 6.9% of control students owning such enterprises, and were less likely to hold a formal job instead. Finally, entrepreneurship programmes may be offered in universities. An example is an experiment in Tunisia which taught entrepreneurial skills during the last year of university. While the study found positive impacts on starting new firms after one year, these effects disappeared over a four-year horizon (Alaref et al. 2020). Frese et al. (2016) report promising impacts after one year on starting new firms for a psychology-based training programme called STEP implemented in universities in four African countries, and the programme has now scaled to ten countries.

Comparing and synthesising impacts from youth business training programmes is difficult for several reasons. The goal of these programmes is often employment, and so one of the main impacts is on whether youth start a firm. But it is not always clear that self-employment is the most desirable employment option, particularly since the business failure rate tends to be highest for youth (McKenzie and Paffhausen 2019). In the longer-run, youth may also be better off investing in schooling rather than starting a business, so examining employment over the longer term is important. Second, because the control group often starts very few firms, measuring the impacts on profitability or sales is difficult because control group means can be low. Looking at total income from all income-earning activities, including wage work, is likely to be a better measure for comparability.

References

Alaref, J, S Brodmann and P Premand (2020), “The medium-term impact of entrepreneurship education on labor market outcomes: Experimental evidence from university graduates in Tunisia”, Labour Economics, 62: 101787.

Alibhai, S, N Buehren, M Frese, M Goldstein, S Papineni and K Wolf (2019), “Full Esteem Ahead? Mindset-oriented business training in Ethiopia”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper no. 8892.

Anderson, S, R Chandy and B Zia (2018), “Pathways to profits: the impact of marketing vs. finance skills on business performance”, Management Science, 64(12): 5559–5583.

Anderson, S and D McKenzie (2020), “Improving Business Practices and the Boundary of the Entrepreneur: A Randomized Experiment Comparing Training, Consulting, Insourcing and Outsourcing”, Journal of Political Economy, 130(1): 157-209.

Arraiz, I, S Bhanot and C Calero (2019), “Less is More: Experimental Evidence on Heuristic-Based Business Training in Ecuador”, IDB Invest Working Paper TN No.18.

Avdeenko, A, M Frölich and S Helmsmüller (2021), “Changing business practices of micro and small enterprises: Evidence from an RCT with 12 financial service providers”, Mimeo. University of Mannheim.

Bakhtiar, M M, G Bastian and M Goldstein (2022), “Business Training and Mentoring: Experimental Evidence from Women-Owned Microenterprises in Ethiopia”, Economic Development and Cultural Change, 71(1): 151-183.

Batista, C, S Sequeira and P Vicente (2021), “Closing the Gender Profit Gap”, Mimeo. Nova School of Business and Economics.

Berge, L, K Bjorvatn and B Tungodden (2015), “Human and Financial Capital for Microenterprise Development: Evidence from a Field and Lab Experiment”, Management Science, 61(4): 707-22.

Berge, L-I O, K Bjorvatn, F Makene, L H Sekei, V Somville, and B Tungodden (2022), “On the Doorstep of Adulthood: Empowering Economic and Fertility Choices of Young Women”, HCEO Working Paper no. 2022-035.

Bloom, N and J van Reenen (2010), “Why do management practices differ across firms and countries?”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 24(1): 203-224.

Brooks W, K Donovan and TR Johnson (2018), “Mentors or teachers? Microenterprise training in Kenya.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, in press.

Brudevold-Newman, A, M Honorati, G Ipapa, P Jakiela, O Ozier (2023), “A Firm of One’s Own: Experimental Evidence on Credit Constraints and Occupational Choice,” Center for Global Development Working Paper 646.

Bruhn, M and B Zia (2013), “Stimulating Managerial Capital in Emerging Markets: The Impact of Business Training for Young Entrepreneurs”, Journal of Development Effectiveness, 5(2): 232–266.

Bruhn, M, G Garber, S Koyama, and B Zia (2022), “The Long-Term Impact of High School Financial Education: Evidence from Brazil.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper no. 10131.

Bulte, E, R Lensink, R van Velzen and T H V Nhung (2016), “Do Gender and Business Trainings Affect Business Outcomes? Experimental Evidence from Vietnam”, Management Science, 63(9): 2885-2902.

Buvinic, M, H C Johnson, E Perova and F Witoelar (2020), “Can Boosting Savings and Skills Support Female Business Owners in Indonesia? Evidence from A Randomized Controlled Trial”, CGD Working Paper 529. Washington, DC.

Calderon, G, J Cunha and G de Giorgi (2020), “Business Literacy and Development: Evidence from a Randomized Trial in Rural Mexico”, Economic Development and Cultural Change, 68(2): 507-540.

Calderone, M, N Fiala, L Melyoki, A Schoofs and R Steinacher (2022), “Making Intense Skills Training Work at Scale: Evidence on Business and Labor Market Outcomes in Tanzania”, RUHR Economic Paper no. 950.

Campos, F, M Frese, M Goldstein, L Iacovone, H C Johnson, D McKenzie and M Mensmann (2017), “Teaching personal initiative beats traditional training in boosting small business in West Africa”, Science, 357(6357): 1287-1290.

Chioda, L, D Contreras-Loya, P Gertler and D Carney (2021), “Making Entrepreneurs: Returns to Training Youth in Hard Versus Soft Business Skills”, NBER Working Paper no. 28845.

Chioda, L, P Gertler and N Perales (2023), “Empowering women: teaching leadership skills to youth in Uganda”, CEDIL Research Project Paper no. 10.

Chong, A and I Velez (2020), “Business training for women entrepreneurs in the Kyrgyz Republic: evidence from a randomized controlled trial”, Journal of Development Effectiveness, 1-13.

Cole, S, M Joshi and A Schoar (2019), “Heuristics on Call: The impact of mobile-phone based financial management advice”, Mimeo. IDEAS 42.

Dalton, P, J Rüschenpöhler, B Uras and B Zia (2020), “Curating Local Knowledge: Experimental Evidence from Small Retailers in Indonesia”, Mimeo. World Bank.

Dammert, A and A Nansamba (2019), “Skills Training and Business Outcomes: Experimental Evidence from Liberia”, Partnership for Economic Policy Working Paper no. 2019-24.

Drexler, A, G Fischer and A Schoar (2014), “Keeping It Simple: Financial Literacy and Rules of Thumb”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 6(2): 1-31.

Frese, M, M Gielnik and M Mensmann (2016), “Psychological Training for Entrepreneurs to take action: contributing to poverty reduction in developing countries”, Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25(3): 196-202.

Giné, X and G Mansuri (2021), “Money or Management? A Field Experiment on Constraints to Entrepreneurship in Rural Pakistan”, Economic Development and Cultural Change, 70(1): 41-86.

Glaub, M, M Frese, S Fischer and M Hoppe (2014), “Increasing Personal Initiative in Small Business Managers or Owners Leads to Entrepreneurial Success: A Theory-Based Controlled Randomized Field Intervention for Evidence-Based Management”, Academy of Management Learning and Education, 13(3): 354–379.

Grohmann, A, L Menkhoff and H Seitz (2021), “The effect of personalized feedback on small enterprises’ finances in Uganda”, Economic Development and Cultural Change, forthcoming.

Karlan, D and M Valdivia (2011), “Teaching Entrepreneurship: Impact of Business Training on Microfinance Clients and Institutions”, The Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(2): 510-527.

McKenzie, D (2021), “Small Business Training to Improve Management Practices in Developing Countries: Re-assessing the evidence for “training doesn’t work””, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 37(2): 276-301.

McKenzie, D and A L Paffhausen (2019), “Small firm death in developing countries”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 101(4): 645-57.

McKenzie, D and C Woodruff (2013), “What are we learning from business training and entrepreneurship evaluations around the developing world?”, The World Bank Research Observer, 29(1): 48–82.

McKenzie, D and C Woodruff (2017), “Business practices in small firms in developing countries”, Management Science, 63(9): 2967-2981.

McKenzie, D and W Puerto (2021), “Growing Markets through Business Training for Female Entrepreneurs: A Market-Level Randomized Experiment in Kenya”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 13(2): 297-332.

Ubfal, D, I Arráiz, D Beuermann, M Frese, A Maffioli and D Verch (2019), “The Impact of Soft-Skills Training for Entrepreneurs in Jamaica”, IZA Discussion Paper no. 12325.

Valdivia, M (2015), “Business training plus for female entrepreneurship? Short and medium term experimental evidence from Peru”, Journal of Development Economics, 113: 33-51.

Vivalt, E (2019), “How much can we generalize from impact evaluations?”, Journal of the European Economic Association, 18(6): 3045-89.

Contact VoxDev

If you have questions, feedback, or would like more information about this article, please feel free to reach out to the VoxDev team. We’re here to help with any inquiries and to provide further insights on our research and content.