The consequences for firms

The papers that seek to identify the effect of formality on firms’ performance typically estimate a regression of the outcome of choice (profits, for example) onto a dummy for whether the firm is formal or not, and additional covariates that capture firms’ (and owners’) observable characteristics. The identification problem then comes from the self-section of firms into formality, which is expected to be positive – i.e. better firms/entrepreneurs self-select into being formal. This decision is likely to be influenced by elements that are unobservable to the econometrician, such as firm-level demand or productivity shocks and unobserved, time-varying entrepreneurial quality. To overcome this identification problem, the literature has largely resorted to experimental or quasi-experimental variation in access to policies and interventions that change the costs and benefits of formalisation, such as those discussed in Section 4.1, to construct instruments for the endogenous regressor of interest, i.e. the formalisation dummy.

The results in the literature generally indicate that formalisation has no statistically significant effects on different measures of firm performance, such as sales, profits and number of employees (e.g. Rocha et al. 2018, Benhassine et al. 2018). Even when the study does find a positive average effect of formalisation on profits, as in De Mel et al. (2013), this seems to be driven by few firms experiencing substantial growth. This lack of effect is consistent with the argument that the perceived benefits of formalisation are very low for most small-scale entrepreneurs (Bruhn and McKenzie 2014). It might be the case that the positive effects of formality take a long time to appear, while most of these studies follow these firms for up to three years. Even if this is the case, these are not very encouraging results, as the costs of formality kick in immediately upon formalisation (such as tax payments), while the benefits would take much longer, if at all.

Perhaps more revealing, even when firms do formalise as a result of the incentives provided, they do not seem to change any meaningful behaviour. De Mel et al. (2013) show that formalisation does not increase tax payments, the likelihood of holding a business bank account nor of applying for a business or personal loan. The only dimension of such intermediary outcomes affected by formalisation is the probability of keeping a receipt book. These results therefore challenge the idea that formalisation per se could have an important causal effect on firms’ performance.

How Taxation and Redistribution are Impacted by the Informal Sector

The existence of large informal sectors in low- and middle-income countries could potentially change the redistributive properties of taxation. This is particularly important for consumption taxes, on which these countries rely to raise a large share of their revenues. Consumption purchased from informal retailers is, by definition, untaxed. If the budget share that households spend in the informal sector varies systematically with income, the presence of informal sectors will change the incidence of consumption taxes. Informal consumption patterns could therefore also affect the desirability of different consumption tax policies. In particular, if much of consumption (especially of poorer households) is outside the formal sector, then this could, for example, substantially reduce the motivation for taxing necessities (food products in particular) at a reduced rate compared to other products.

Bachas et al. (2024) investigate the patterns of informal consumption and their implications for tax policy in 32 developing countries of varying levels of economic development (from Burundi to Chile). Informal sector purchases are by definition hard to observe and link to consumers’ incomes. To overcome this challenge, they use the places of purchase reported by households in expenditure surveys to proxy for the share of consumption in the informal sector. Building on evidence from retail censuses and existing literature, they assign each place of purchase to the informal or formal sector, based on the idea that large modern retailers are much more likely to remit taxes than smaller traditional ones (Lagakos 2016, Kleven et al. 2016). They assume, for example, that consumption from home production, markets and street stalls is informal, whilst consumption from supermarkets is formal.

The key descriptive result of their paper is the existence of a downward-sloping Informality Engel Curve (IEC): they find that, in all countries, the informal budget share declines steeply with household income. Figure 4 shows this in Rwanda and Mexico as an example. In Rwanda, the informal budget share falls from 90% for the poorest decile of households to 70% for the richest decile. In Mexico, it falls from 55% to 25%.

Figure 4: Informality Engel curves in Rwanda and Mexico

Notes: Figures reproduced from Bachas et al. (2021). These panels show the local polynomial fit of the informality Engel curves in Rwanda (Panel A) and Mexico (Panel B). Per person total expenditure on the horizontal axis is measured in log. Informal budget share is on the vertical axis. The shaded area around the polynomial fit corresponds to the 95% confidence interval. The solid grey line corresponds to the median of each country’s expenditure distribution, while the dotted lines correspond to the 5th and 95th percentiles.

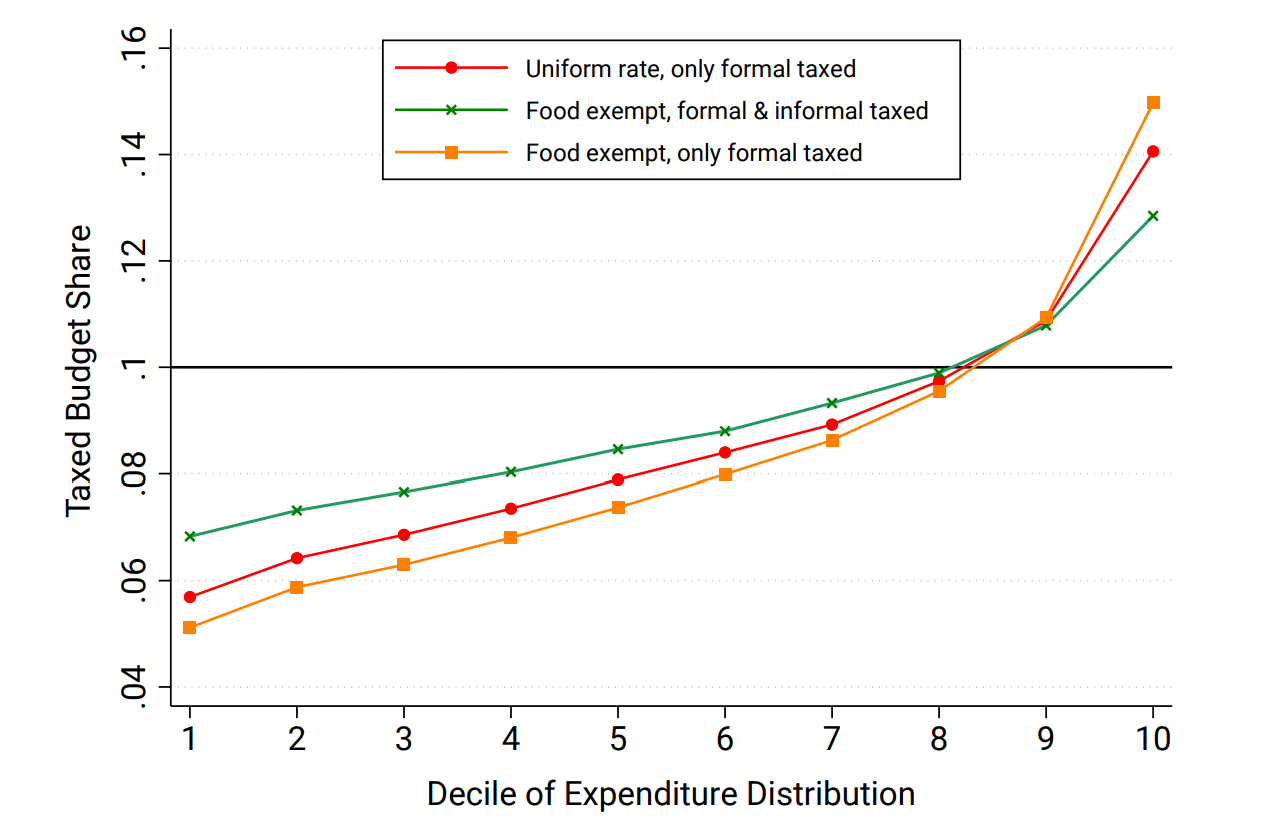

The shape of the informality Engel curves implies that informal consumption patterns make consumption taxes progressive. Simply setting a uniform tax rate on all goods would lead to the richest quintile paying twice as much in taxes as the poorest quintile in the average (Figure 5, red line). As a comparison, Figure 5 plots the taxed budget share obtained under the ‘naïve’ assumption that governments can tax all expenditures but choose to exempt food from taxation (green line). Comparing the green and red lines, one can see that the de facto exemption of the informal sector from taxation is clearly more progressive than this naïve scenario. Results country-by-country in the paper show that this ‘progressivity dividend’ from exempting the informal sector is largest in the poorest countries. The small size of the formal sector in these countries, together with the downward-sloping informality Engel curves, makes formal transactions a particularly good ‘tag’ for household income. Finally, once the informal sector is taken into account, we see that exempting food items from taxation only slightly increases progressivity (orange line). This is because the formal food Engel curve actually has a small but positive slope in the poorest countries.

Figure 5: Taxed budget shares, average across all countries

The authors then use a simple model to study optimal consumption tax policy in the presence of an informal sector, and calibrate it using their data. The existence of the informal sector affects both the equity characteristics of consumption taxes (via the shape of the Informality Engel Curves) and their efficiency: informality increases the efficiency cost of taxing consumption because households can switch to informal varieties of products when taxes on formal ones increase. They find that, in some of the poorest countries, subsidising food relative to non-food is simply not optimal once the informal sector is taken into account. Since, in these countries, poor households consume most of their food from the informal sector, the subsidy ends up either redistributing very little or benefiting mostly richer households.

Overall, the evidence indicates that the presence of large informal sectors in developing countries make consumption taxes progressive. These results caution that any benefits from reducing the informal sector's size should be weighed against potential equity costs. These findings more generally suggest that informality may affect the distributional consequences of tax policy in developing countries in subtle ways, an important avenue for future research.

Aggregate Consequences of the Informal Sector

Informality is an endogenous outcome as much as the unemployment rate or wages observed in a given economy. As such, the aggregate effects of having lower or higher levels of informality are ultimately determined by the means used to achieve a lower level of informality. Both the (more extensive) macro literature and the recent structural literature have approached this question using calibrated/estimated models and relying on counterfactual exercises relative to specific policy experiments. These can be largely classified as those that increase the costs of informality or reduce the costs (or increase the benefits) of formality. In what follows we discuss the main results of the literature by different types of aggregate outcomes in counterfactual exercises that emphasise policy experiments in both of these categories.

Human capital

Two recent papers (Bobba et al. 2021, Bobba et al. 2022) investigate the negative relationship between informality and the stock of human capital in the economy, considering both investments prior to labour market entry and on-the-job human capital accumulation. The broad idea behind both papers is that informality can work as a “tax” on human capital in developing countries. The authors consider a class of equilibrium search and matching models of the labour market aimed at capturing two empirical regularities that are hard to explain in models where the market is competitive or where there is segmentation between the formal and the informal sector: (i) individual workers transition frequently between formal and informal jobs; and (ii) conditional on workers’ schooling level, formal and informal earnings distributions overlap.

The framework in Bobba et al. (2022) allows for workers to decide on their schooling level prior to entering the labour market. The education decision depends on the present discounted value of participating in a schooling-specific labour market with returns resulting from all the factors discussed above. A key finding is that informality depresses the returns to schooling. Since workers anticipate this, they will invest less in their education, and therefore the proportion of workers acquiring a given level of schooling will fall. The mechanism is as follows: the institutions that generate informality tax high-productivity formal jobs and increase the relative profitability of informal self-employment and of low-productivity informal salaried jobs. These taxes and subsidies differ across schooling levels, hurting relatively more those workers with more schooling. Precisely because those workers are more productive, it is harder for firms to offer them informal jobs (since expected penalties are higher). In addition, because some benefits are pooled, when workers with more schooling are formally employed, they subsidise those with less schooling

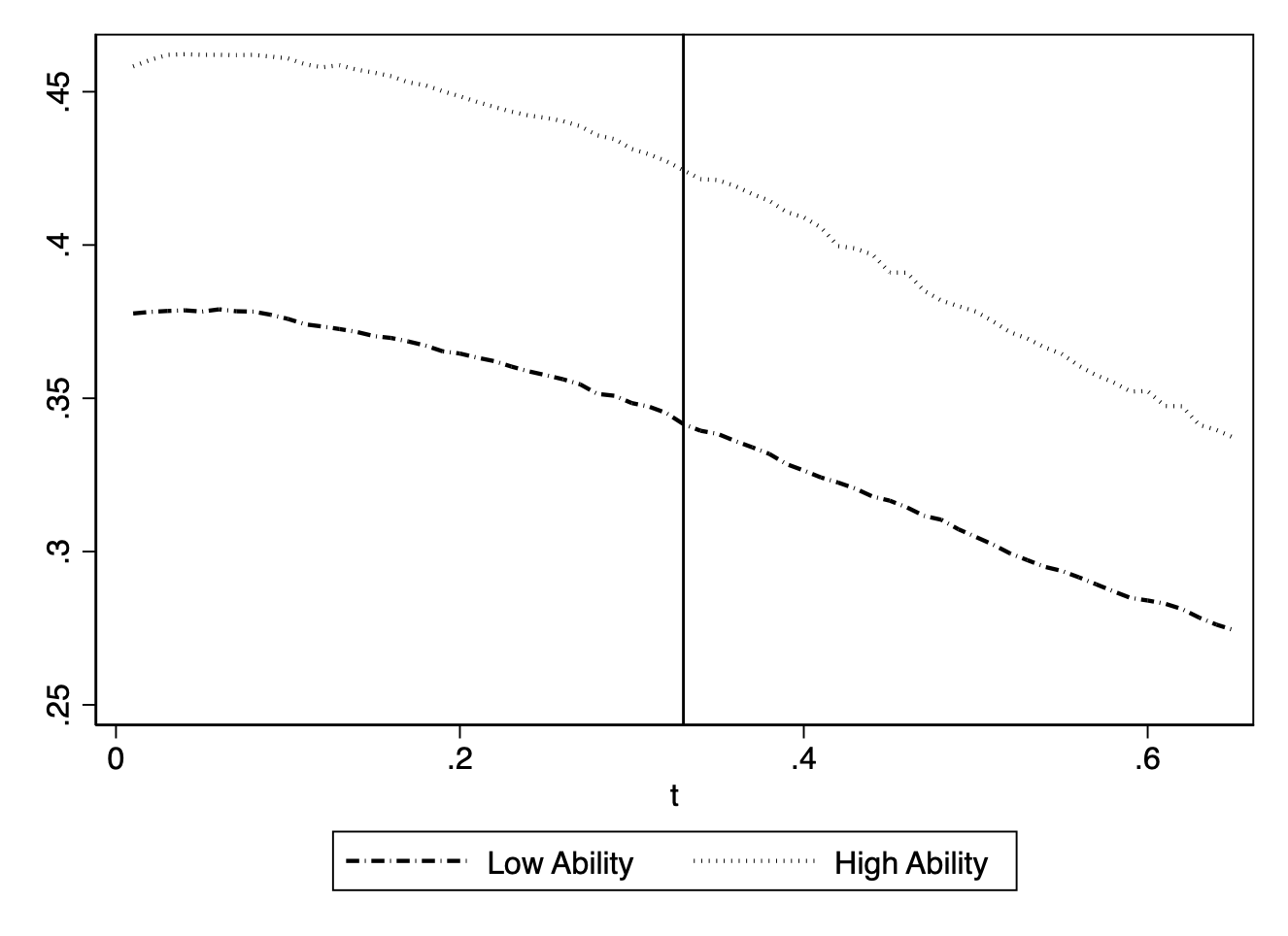

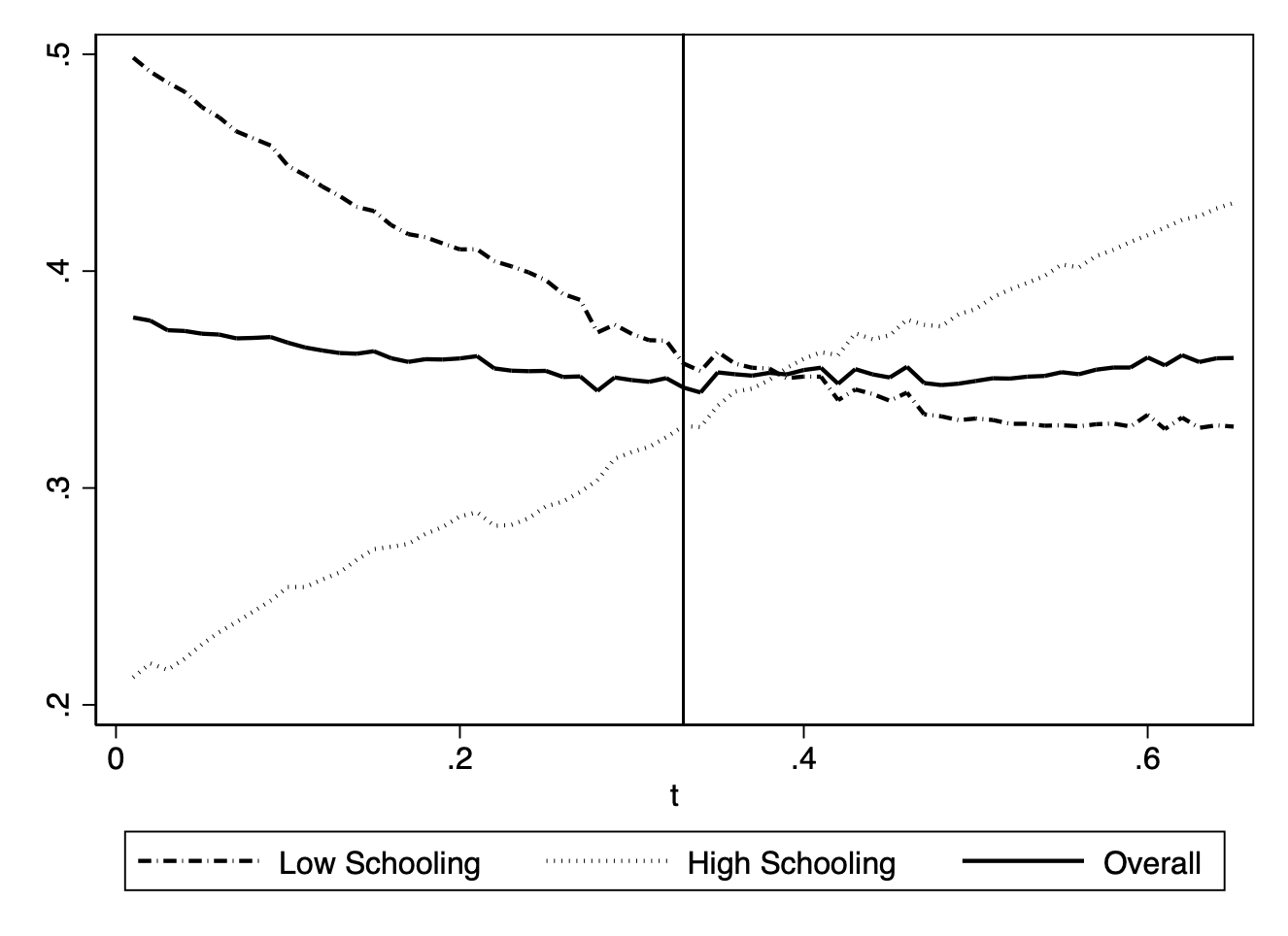

The parameters of the model are estimated using data from Mexico, a country where more than half of the labour force is informally employed.[1] Two sets of counterfactual experiments based on the estimated model quantify the effects of informality on schooling. First, eliminating informal jobs enhances labour market returns to schooling and increases schooling investments by 10% but at the cost of decreasing welfare for both workers (5%) and firms (28%). This trade-off originates from the fact that taxes and subsidies operate through the labour market and are associated with the formality status of the job. Second, the proportion of individuals who acquire the higher schooling level decreases monotonically with the payroll tax rate – as shown in panel a) of Figure 6. Interestingly, these changes in schooling are paired with an almost constant informality rate (panel b). The phenomenon is explained by major composition effects resulting from the progressive features of the contributory social security benefits: as the tax rate increases, a proportionally larger benefit is available to lower earnings individuals.

Figure 6: The effect of changes in the payroll tax rate on schooling and informality

Panel A: Schooling by ability

Panel B: Informality by schooling

Bobba et al. (2021) consider a similar framework where workers are homogenous before entering the labour market and are allowed to accumulate human capital while on-the-job. The human capital evolution while participating in the labour market captures the additional productivity that may be acquired on the job. The authors allow this dynamic to depend on the formality status of a job. While off-the-job and searching (either as unemployed or as self-employed), individuals may even lose previously accumulated knowledge, leading to a depreciation of human capital. Estimation results show that human capital accumulation on the job occurs more rapidly when workers are formally employed. For first entrants in the labour market, it takes on average 1.4 years to start upgrading their human capital if they work formally but it takes 40% longer to do so if they work informally. Human capital upgrading is harder the higher the stock of skills already acquired on the job but, at any human capital level, the probability of upgrading remains higher if working formally. Policy experiments reveal that on-the-job human capital accumulation magnifies the negative impact on productivity of labour market institutions that give raise to informality. For example, the increase in Seguro Popular benefits (see Section 4.3) over the course of 10 years is associated with a drop in aggregate human capital of about 5 percentage points.

Labour Market Power

The frictions to firm growth in low- and middle-income countries – such as high entry costs, a shortage of skilled labour, and inadequate infrastructure – can result in the concentration of employment among a few firms. Relatively large firms may thus internalise their impact on local labour market conditions, thereby strategically reducing wages to increase profits. In these contexts, informal jobs may represent a valuable outside option for workers. Workers can easily switch between informal wage work, or self-employment, and formal wage work within a local labour market, and thus they can opt for informal jobs when posted wages in the formal sector are too low.

A recent working paper by Amodio et al. (2024) formalises this idea using Peruvian data and an equilibrium model that features firms’ oligopsony power that varies across local labour markets as well as heterogenous workers’ sorting across wage work and self-employment based on earnings. In the model, informal self employment plays a dual role in the presence of labour market power. It can shield workers from the wage setting power of firms by providing a livelihood when wage opportunities are scarce. However, when formal employment becomes more attractive, lower self-employment rates decrease the labour supply elasticity in the formal sector possibly having anti-competitive effects in the labour market. This second channel would make it more difficult for policies that seek to boost formal employment and wages to succeed.

Another key source of labour market power is different preferences of workers over job amenities. If jobs are differentiated even small firms face upward sloping labour supply curves, which they internalise by reducing wages relative to the competitive benchmark. Although not related to informal jobs, two recent contributions provide direct empirical evidence of this phenomenon in the context of labour markets in developing countries. Sharma (2023) shows that in Brazil job amenities that are particularly valued by women also confer their employers with higher monopsony power. This channel explains a non-negligible fraction (18 percentage points) of the gender wage gap in the textile and clothing manufacturing industry. Again, in Brazil, Felix (2022) documents that trade liberalisation increased local labour market concentration by 7%, an effect driven by firm exit and labour reallocation towards exporters that raised wage markdowns.

Productivity, output and growth

Reducing Informality via Higher Enforcement

A common feature of most informality models is the presence of a cost of informality that is increasing in firm size, which is typically measured as number of employees, capital or revenues (e.g. Fortin et al. 1997, De Paula and Scheinkman 2011, Ordonez 2014, Meghir et al. 2015, Ulyssea 2018). Thus, a common counterfactual experiment found in the literature is to simulate higher enforcement on informal firms by making this cost function steeper. The basic intuition is that higher enforcement – via intensified inspections, say – increases the cost of operating as an informal firm (due to a higher probability of detection, for example), which would lead to a substantial reduction of informality.

The results from different studies indicate that reducing the size of the informal sector by increasing enforcement could lead to substantial gains in aggregate productivity. As summarised in Ulyssea (2020), different mechanisms contribute to generating these positive effects. First, there are positive composition effects, as greater enforcement eliminates many low-productivity (informal) firms, which then frees up resources that are reallocated to more productive formal firms (e.g. Ulyssea 2010, Charlot et al. 2015, Bosch and Esteban-Pretel 2012, Meghir et al. 2015, Ulyssea 2018). Second, reducing the availability of low-quality informal jobs can make it easier for workers to find higher quality formal jobs, especially if there are substantial labour market frictions (e.g. Meghir et al. 2015). Third, because informal firms face higher financial frictions and are more credit constrained, formalisation can lead to greater capital accumulation (e.g. D’Erasmo and Boedo 2012, Ordonez 2014). Fourth, it affects occupational choices by discouraging low-skill individuals to self-select into informal entrepreneurship, therefore increasing labour supply in the formal sector (e.g. Ordonez 2014, Lopez 2017). Fifth, as discussed in the previous section, there can be higher investments in formal schooling (before entering the labour market) and on-the-job human capital accumulation (Bobba et al. 2021, 2022).

Despite these positive aggregate effects, higher enforcement can have adverse effects on those directly affected and potentially on aggregate outcomes as well. In an earlier paper, Boeri and Garibaldi (2005) argued that large informal sectors are “tolerated” by governments because increasing enforcement could lead to substantial increases in unemployment. The results in Ulyssea (2010) and Charlot et al. (2015) are consistent with this conjecture. Using equilibrium matching models calibrated to the Brazilian economy, they show that greater enforcement substantially reduces informality, but at the cost of increasing unemployment. More recently, Meghir et al. (2015) and Haanwinckel and Soares (2021) find no unemployment effects from higher enforcement. Dix-Carneiro et al. (2024) show non-monotonic effects: stricter enforcement barely changes unemployment, but completely eradicating the informal sector causes the unemployment rate to increase substantially.

One of the key dimensions to determine the extent of the positive effects on productivity and the negative effects on unemployment is how much employment reallocation there can be from lowproductivity informal firms to more productive formal firms. A second important, and completely overlooked, question is how lengthy the transition between steady states is, and therefore how long this reallocation process can take. This is key for both the political economy of implementing these measures, but also to determine the welfare costs in the short- and medium-run for those negatively affected by these policies.

Even though most of the literature focuses on enforcement policies on the extensive margin of informality (i.e. increasing the costs of informal firms), Ulyssea (2018) shows that increasing enforcement on the intensive margin can generate very different results. In particular, even though it reduces informality amongst workers, it can in fact increase the share of informal firms. This occurs because higher enforcement in the intensive margin effectively increases the costs of operating in the formal sector for small formal firms. Hence, many of these firms choose to enter the informal rather than the formal sector in the new equilibrium. As a consequence, this policy generates losses for low-productivity formal firms, while highproductivity firms benefit from it in terms of higher life-time profits. The effects on aggregate productivity are small – an increase of 1.7% – and output decreases by 1.6%, as the reduction in the number of firms operating in the economy more than compensates the small gains in aggregate productivity.

Finally, Almeida and Carneiro (2009) use micro data to estimate average aggregate effects of enforcement across municipalities in Brazil. For that, they exploit the fact that enforcement of labour regulation (the intensive margin of informality) is implemented in a decentralised way and displays a lot of variation across local economies. They use an IV estimator to show that an increase in the number of inspections per hundred formal firms leads to small reductions in output and firm size. In a follow-up paper Almeida and Carneiro (2012) show that more inspections also lead to small negative effects on the share of formal workers and self-employed and an increase in non-employment.

The results by Ponczek and Ulyssea (2022) mentioned in previous sections directly speak to this discussion as well. They examine the effects of local economic shocks generated by the unilateral trade liberalisation in Brazil, and how they varied across regions with weaker and stronger enforcement levels. This unilateral trade opening essentially represented a negative demand shock to the affected industries in Brazil, which generated heterogeneous effects across regions where employment was more and less concentrated in these industries. As mentioned in Section 4.2, the authors show that regions with stricter enforcement experienced lower informality effects, but greater losses in overall employment and greater reductions in the number of formal plants. Regions with weaker enforcement had opposite effects and all the effects are concentrated among low-skill workers. Thus, similarly to Bujanda and de la Parra (2020), these results indicate that greater enforcement can lead to greater formalisation but with potentially adverse employment effects. Conversely, the greater flexibility introduced by informality might allow formal firms and low-skill workers to cope better with adverse labour market shocks (Ponczek and Ulyssea 2022).

Reducing the costs of formality

As discussed in Section 4.1, the literature that uses experimental and non-experimental empirical designs to estimate the effects of reducing the costs of formality on firms’ decisions to formalise shows essentially zero or very limited effects. Despite the importance of these results, it can still be the case that these policies could have important aggregate effects. Indeed, one of the regularities that emerges from counterfactual exercises in different papers is that reducing fixed entry costs into the formal sector can produce positive and sizeable aggregate effects (Ulyssea 2010, D’Erasmo and Boedo 2012, Charlot et al. 2015, Ulyssea 2018). For example, Ulyssea (2018) shows that reducing entry costs into the formal sector leads to higher competition, aggregate production in the formal sector and high-skill wages. However, because it is mostly low-productivity firms that formalise, there is a negative composition effect that leads to a decrease in aggregate productivity. Total output still increases because there is a substantial increase in the number of firms in the economy led by an increase in the number of formal firms (Ulyssea (2010) and Charlot et al. (2015) find similar positive aggregate effects, including lower unemployment).

If, however, there are important frictions in the formal sector as well – such as financial frictions – then these positive effects can be limited. That is the case in Lopez-Martin (2018), who finds limited aggregate effects from reducing entry costs in Mexico and Egypt, of at most 0.5 and 0.7 percentage points in aggregate productivity and output per capita, respectively. It is only when financial frictions in the formal sector (modelled as the ability of firms to collateralise their assets) are relaxed that the economies observe substantial gains in aggregate productivity, output and welfare (D’Erasmo 2016 finds similar results).

As also discussed in Section 4.1, the empirical evidence suggests that reducing the tax burden can induce some formalisation of informal firms, but even in this case the effects are not very large. The counterfactual results from macro and structural models corroborate that: reductions in payroll tax seem to generate some positive but limited formalisation effects (e.g. D’Erasmo and Boedo 2012, Haanwinckel and Soares 2021). Ulyssea (2018) shows that these effects are stronger on labour informality (via the intensive margin) and weaker on firm informality. The overall effects on aggregate productivity and output are also positive but quite limited (Ulyssea 2010, D’Erasmo and Boedo 2012, Haanwinckel and Soares 2021, Ulyssea 2018).

Housing formalisation

A recent line of research analyses housing informality using rich equilibrium models of cities (à la Ahlfeldt et al. 2015), which emphasise the linkages across neighbourhoods via individuals’ decisions about where to live and work, and externalities such as congestion and agglomeration forces. These models typically feature formalisation costs to convert land from informal to formal, which reflect the cost of regulation in the formal market but also land assembly and relocation costs associated with clearing slums. One of the core themes analysed using this class of models is the equity-efficiency tradeoff involved in preserving slums at the expense of formal development. Formal neighborhoods yield higher land values, taller buildings, and enhanced agglomeration benefits. On the other hand, low-height informal housing provides shelter for many residents, enabling them to live in locations with high access to labour markets.

In Gechter and Tsivanidis (2023), the demand side features heterogeneous households, low- and high-skill, choosing where to live, where to work, and whether to consume formal or informal housing, subject to eviction risk. On the supply side, developers optimally choose whether to provide formal housing, subject to formalisation costs, or informal housing, subject to a technological height constraint. They employ this framework to characterise the local and spillover effects of building high-rises in previously unbuildable areas of Mumbai, India. Their counterfactual analysis shows that, in aggregate, building high-rises benefits formal residents and firms, but induces gentrification of nearby informal settlements inflicting large costs on forcibly displaced slum dwellers. They also consider alternate compensation schemes that preserve most of the aggregate gain but improve equity. Harari and Wong (2024) employ a similar model to shed light on these tradeoffs leveraging policy variation from a slum upgrading scheme (see below).

Henderson et al. (2020) calculate that converting Nairobi’s largest slum into a formal area would yield large gains in an amount equivalent to thirty times the typical annual slum rent payments for each displaced slum household. They point to slum landlords benefiting from the status quo as a key obstacle to reallocating land toward formal use.

Slums and Social Mobility

One of the open questions is whether slum residents are “stuck” in a poverty trap - characterised by low human capital accumulation and limited mobility (Marx et al. 2013) – or whether slums provide access to urban economic opportunities that would otherwise be out of reach due to high formal housing costs (Glaeser 2011).

We lack the individual-level data required to shed light on these two competing narratives in a definitive way, but the answer is likely to be context-specific. Several studies suggest that low-quality housing in slums adversely affects health and well-being (Cattaneo et al. 2009, Galiani et al. 2017). However, the evidence on mobility is mixed: Wong (2019) describes patterns suggestive of educational and mobility gains across generations of slum dwellers in Jakarta, Indonesia. In a survey of slum dwellers in Delhi, India, Banerjee et al. (2012) find that a significant portion are recent migrants, suggesting considerable churn, which contrasts with the view of slums as static “traps”. However, Krishna (2013) finds that a majority of slum dwellers in Bangalore, India, have lived in slums for many generations and exhibit little mobility.

Evidence on the link between housing informality and labour market outcomes is also mixed. On one hand, tenure insecurity has been found to reduce labour supply: Field (2007) finds that a titling programme in Lima, Peru, led to increases in labour supply, as residents no longer had to stay home to guard against evictions or land grabs. This is in line with findings by Franklin (2020) for Cape Town, South Africa. At the same time, the literature on relocations (see below, e.g. Barnhardt et al. 2017) suggests, by revealed preferences, that slums may provide favourable access to jobs. Notably, these findings mainly come from studies where slum residents were originally in relatively central locations. While many slums are in accessible locations (Harari 2024), others are in peripheral areas (Galiani et al. 2017), so the degree of labour market access likely varies considerably.

Public Polices towards Slums

Many developing country governments have a stated objective to become “slum free,” in line with Sustainable Development Goal 11.1.

There are several common policy approaches. Titling programmes have been introduced as a market-based solution to secure property rights. Inspired by the influential work of De Soto (2000), titling aims to incentivise private housing investments and facilitate access to credit by enabling property to be used as collateral.

The household-level impacts of titling programmes in the literature are generally positive, yet not transformative. Leveraging the phased implementation of a large-scale land titling programme in Lima, Peru, Field (2005) finds that titling increases private investment and labour supply, but there is limited evidence of credit effects (Field and Torero 2006). Galiani and Schargrodsky (2010) similarly find improvements in investments and education in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

At the city level, implementing titling at scale is challenging because land registration is often complicated by fees, land disputes, moral hazard, and backlogged courts. Successful titling requires establishing a bundle of institutions, including mapping and a registration system. Recent pathways to enhance property rights institutions include technological advances in land mapping (e.g. LIDAR surveying) and leveraging the role of local leaders (Manara and Regan 2022).

Another common government intervention involves the relocation of slum residents. While evictions without compensation were common in the 1950s, most subsequent government-sponsored slum clearance schemes involve some form of compensation, sometimes in the form of subsidised formal housing. Relocations remain politically charged, as compensation is often thought to be below market value. Due to budget constraints, public housing is often located in peripheral neighbourhoods with low market access, where land is inexpensive. A priori, the effects on residents are ambiguous: beneficiaries experience improvements in tenure security, housing quality, and wealth effects from becoming homeowners, but relocating to a different neighbourhood can be disruptive, leading to a loss of networks and reduced access to jobs and amenities.

A growing literature documents the effects of relocation schemes. A common lesson is that displacement can be very harmful for relocated residents, and labour market access in destination locations is crucial to determining the net effects.

Barnhardt et al. (2017) track beneficiaries of a housing lottery in Ahmedabad, India, offering slum dwellers from relatively central neighbourhoods subsidised formal housing in the periphery. Fourteen years later, they find low take-up and significant programme exit among lottery winners, as well as losses from network disruption.

The importance of job access in the destination locations is exemplified by the mixed evidence on a large public housing scheme implemented in South Africa over the past two decades. Picarelli (2019) studies the nationwide programme, exploiting a cutoff in the selection rule, and shows that rehousing to areas with low labour market access negatively affects household outcomes. Franklin (2020) focuses on beneficiaries who were rehoused nearby in Cape Town. Leveraging quasi-experimental variation in programme selection, he finds positive labour supply effects associated with housing improvements. Similarly, Kumar (2021) examines a lottery providing housing on-site in Mumbai, India, and finds positive impacts on housing quality, income, education, and employment rates.

In contrast with some of the previous studies, Franklin (2024) and Agness and Getahun (2024) find positive effects from a large scale subsidised housing lottery in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, providing improved housing in the outskirts of the city. Franklin (2024) finds that nearly half of lottery winners chose to leave central slums for condo housing in the periphery. While amenities and social were initially worse, the destination neighbourhoods improve over time and see business formation, with no negative impacts on labour market outcomes, education, or consumption. Agness and Getahun (2024) focus on children’s human capital outcomes and find large gains in school attendance and completion rates, as well as positive effects on formal employment among adults in the medium run.

Belchior et al. (2024) analyse the effects of the Minha Casa Minha Vida housing lottery programme in Brazil and document similar take up rates as those in Franklin (2024) among lottery winners who are allocated to houses in the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro. Consistent with most of the previous literature, they show that the programme has no significant effects on formal employment, wages, or job quality within the six years following the lottery for the overall population of beneficiaries. For low socioeconomic status beneficiaries, however, receiving a house results in increased formal employment and a substantial reduction in welfare dependency. These positive impacts on formal employment are concentrated among individuals randomly assigned to the neighbourhood with the highest access to formal jobs, despite it having worse social indicators. Their bounding exercise indicate that differences in labour market access across neighborhoods explain 83-94% of the variation in neighbourhood-specific outcomes for disadvantaged beneficiaries.

Rojas-Ampuero and Carrera (2023) innovate on the prior literature by constructing a unique householdlevel dataset with which they track programme beneficiaries and their children. They provide evidence on intergenerational effects of a large-scale slum clearance and relocation programme in Santiago, Chile. Using a propensity score approach, they compare residents of slums slated for clearance and relocation to peripheral areas versus those chosen for formalisation on-site. They find marked negative effects on displaced children in terms of earnings and health, mediated by lower education and worse labour market access in the destinations. Slum upgrading and “sites and services” are other common policy approaches that were historically popularised as alternatives to slum clearance.

Slum upgrading consists of providing basic public goods (such as road paving or drainage) on-site in slums, without relocating residents. To encourage private investments, basic upgrades are often bundled with informal guarantees that residents will not be evicted or occupancy certificates.

Proponents of slum upgrading emphasise that these programmes can provide immediate relief to the living conditions of residents and alleviate negative externalities at a fraction of the cost of public housing and without inducing displacement. However, a concern is that the improvements may make slums more crowded (Fox 2014) and ultimately prolong their persistence, leading to potential land misallocation once the city starts formalising.

Harari and Wong (2024) study the long-term effects of the world’s largest slum upgrading programme, implemented in Jakarta, Indonesia, in the late 1960s. Leveraging localised comparisons between historical slums that received upgrades and nearby ones that did not, they find that, decades later, upgraded neighbourhoods are more likely to have remained slums, with lower land values and building heights. These impacts are concentrated in central areas where formal land values are high. Using a spatial equilibrium model, they highlight equity-efficiency trade-offs: in central areas, slum upgrading and the ensuing persistence of slums is associated with aggregate losses, while in other parts of the city, the benefits of upgrading outweigh the costs.

Leveraging a unique panel of slums across cities in Chile, Gertler et al. (2024) find that slum upgrading is associated with better housing and neighbourhood quality and higher socio-economic status among residents compared to slums subject to relocation programmes.

In contrast with the above approaches, “sites and services” target areas that are not yet settled. These programmes involve creating planned neighborhoods with regular, spaced-out plots and basic infrastructure (e.g. roads and pipes) before residents move in. Low-income households receive serviced land rather than fully built homes and construct their own housing. This approach aims to make housing more affordable and address some coordination failures associated with unplanned settlements, offering a cost-effective alternative to public housing.

Michaels et al. (2021) evaluate a large-scale sites and services programme across seven cities in Tanzania using a spatial discontinuity design. Decades later, they find that planned neighbourhoods are more orderly and feature better-quality housing compared to neighbourhoods that underwent slum upgrading or no intervention. However, the effectiveness of de novo planning in alleviating slum conditions may be limited, as these neighbourhoods were ultimately settled by middle-income, rather than low-income households. This was partly due to plot sizes being too large to cater to the low-income market (Henderson et al. 2024). More generally, this policy approach appears viable for cities at earlier stages of development that still have land availability in peripheral areas.

References

Agness, T and M Getahun (2024), "The Long-Term Human Capital Effects of Subsidized Housing: Evidence from Ethiopia." Working Paper.

Ahlfeldt, G M, S J Redding, D M Sturm, and N Wolf (2015), “The economics of density: Evidence from the Berlin Wall,” Econometrica 83(6): 2127–2189. doi:10.3982/ECTA10876.

Almeida, R and P Carneiro (2009), “Enforcement of labor regulation and firm size”, Journal of Comparative Economics, 37:28 – 46.

Almeida, R and P Carneiro (2012), “Enforcement of labor regulation and informality”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 4: 64-89.

Amodio, F., P. Medina, and M. Morlacco (2024), “Labor Market Power, Self-Employment, and Development”, Working Paper.

Bachas, P., L. Gadenne, and A. Jensen (2024), “Informality, consumption taxes, and redistribution”, Review of Economic Studies 91(5): 2604-2634.

Banerjee, A, et al. (2012), “Delhi’s slum-dwellers: Deprivation, preferences, and political engagement among the urban poor,” Policy Brief, International Growth Centre.

Banerjee, A V, R Hanna, G E Kreindler and B A Olken (2017), “Debunking the stereotype of the lazy welfare recipient: Evidence from cash transfer programs”, The World Bank Research Observer, 32:155–184.

Barnhardt, S, E Field and R Pande (2017), “Moving to opportunity or isolation? Network effects of a randomized housing lottery in urban India,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 9(1): 1–32. doi:10.1257/app.20150397.

Benhassine, N, D McKenzie, V Pouliquen and M Santini (2018), “Does inducing informal firms to formalize make sense? Experimental evidence from Benin”, Journal of Public Economics, 157:1–14.

Bergolo, M and G Cruces (2021), “The anatomy of behavioral responses to social assistance when informal employment is high”, Journal of Public Economics, 193: 104313.

Bobba, M, L Flabbi, S Levy and M Tejada (2021), “Labor market search, informality, and on-the-job human capital accumulation”, Journal of Econometrics, 223: 433–453.

Bobba, M, L Flabbi and S Levy (2022), “Labor market search, informality and schooling investments”, International Economic Review, 63: 211–259.

Boeri, T and P Garibaldi (2005), “Shadow sorting”, in NBER Macroeconomics Annual, eds. C Pissarides & J Frenkel, MIT Press, 125-170.

Bosch, M and J Esteban-Pretel (2012), “Job creation and job destruction in the presence of informal markets”, Journal of Development Economics, 98:270–286.

Bruhn, M (2011), “License to Sell: The Effect of Business Registration Reform on Entrepreneurial Activity in Mexico”, Review of Economics and Statistics 93(1): 382-386.

Bruhn, M and D McKenzie (2014), “Entry regulation and the formalization of microenterprises in developing countries”, The World Bank Research Observer, 29:186-201.

Camacho, A, E Conover and A Hoyos (2013), “Effects of Colombia’s social protection system on workers’ choice between formal and informal employment”, The World Bank Economic Review 28:446-466.

Cattaneo, M D, et al. (2009), “Housing, health, and happiness”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 1(1): 75-105. doi:10.1257/pol.1.1.75.

Charlot, O, F Malherbet and C Terra (2015), “Informality in developing economies: Regulation and fiscal policies”, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 51:1-27.

Corbi, R, T Ferraz and R Narita (2024), “Internal migration and labor market adjustments in the presence of non-wage compensation”, Working Paper.

Cruces, G, G Porto and M Viollaz (2018), “Trade liberalization and informality in Argentina: Exploring the adjustment mechanisms”, Latin American Economic Review, 27:1-29.

De Giorgi, G and A Rahman (2013), “SME’s registration: Evidence from an RCT in Bangladesh”, Economics Letters, 120:573-578.

De Mel, S, D McKenzie and C Woodruff (2013), “The demand for, and consequences of, formalization among informal firms in Sri Lanka”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 5:122-150.

De Paula, A and J A Scheinkman (2010), “Value-added taxes, chain effects, and informality”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 2:195-221.

De Soto, H (1989), The Other Path, Harper & Row, New York.

Delgado-Prieto, L (2024), “Immigration, wages, and employment under informal labor markets”, Journal of Population Economics 37(2): 55.

Derenoncourt, E, F Gérard, L Lagos and C Montialoux (2021), “Racial Inequality, Minimum Wage Spillovers, and the Informal Sector”, Working Paper.

D’Erasmo, P N and H Boedo (2012), “Financial structure, informality and development”, Journal of Monetary Economics, 59:286-302.

D’Erasmo, P N (2016), “Access to credit and the size of the formal sector”, Economia 16:143-199.

Dix-Carneiro, R and B K Kovak (2019), “Margins of labor market adjustment to trade”, Journal of International Economics, 117:125-142.

Dix-Carneiro, R, P K Goldberg, C Meghir and G Ulyssea (2024), “Trade and Domestic Distortions: The Case of Informality”, NBER Working Paper 28391.

Dube, A and A S Lindner (2024), “Minimum Wages in the 21st Century”, Working Paper.

El Badaoui, E, E Strobl and F Walsh (2017), “Impact of internal migration on labor market outcomes of native males in Thailand”, Economic Development and Cultural Change 66(1): 147-177.

Engbom, N and C Moser (2022), “Earnings Inequality and the Minimum Wage: Evidence from Brazil”, American Economic Review 112(12): 3803-3847.

Feler, L and J V Henderson (2011), “Exclusionary policies in urban development: Under-servicing migrant households in Brazilian cities”, Journal of Urban Economics 69(3): 253-272. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2010.09.006.

Felix, M (2022), “Trade, Labor Market Concentration, and Wages”, Working Paper.

Finamor, L (2024), “Labor market informality, risk, and insurance”, Mimeo.

Fortin, B, N Marceau and L Savard (1997), “Taxation, wage controls and the informal sector”, Journal of Public Economics, 66:293-312.

Fox, S (2014), “The political economy of slums: Theory and evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa”, World Development 54:191-203. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.08.005.

Franklin, S (2020), “Enabled to work: The impact of government housing on slum dwellers in South Africa”, Journal of Urban Economics 118, article 103265. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2020.103265.

Franklin, S (2024), “The demand for government housing: Evidence from lotteries for 200,000 homes in Ethiopia”, International Growth Centre.

Fredriksson, P G, S K Gupta, W Zhao and J R Wollscheid (2023), “Legal heritage and urban slums”, Journal of Regional Science 63(1): 236-252. doi:10.1111/jors.12622.

Galiani, S, et al. (2017), “Shelter from the storm: Upgrading housing infrastructure in Latin American slums”, Journal of Urban Economics 98:187-213. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2016.11.001.

Galiani, S and E Schargrodsky (2010), “Property rights for the poor: Effects of land titling”, Journal of Public Economics 94:700-729. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2010.06.002.

Gechter, M and N Tsivanidis (2023), “Spatial spillovers from high-rise developments: Evidence from the Mumbai Mills”, Working Paper.

Gerard, F, J Naritomi and J Silva (2024), “Cash Transfers and the Local Economy: Evidence from Brazil”, Working Paper.

Glaeser, E L (2011), Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier, Penguin Books.

Goldberg, P K and N Pavcnik (2003), “The response of the informal sector to trade liberalization”, Journal of Development Economics, 72:463-496.

Gonzalez-Navarro, M and R Undurraga (2023), “Immigration and slums”, Working Paper.

Haanwinckel, D (2024), “Does regional variation in wage levels identify the effects of a national minimum wage?”, Mimeo.

Haanwinckel, D and R R Soares (2021), “Workforce composition, productivity, and labor regulations in a compensating differentials theory of informality”, The Review of Economic Studies, 88:2970-3010.

Harari, M and M Wong (2024), “Slum upgrading and long-run urban development: Evidence from Indonesia”, Review of Economic Studies, forthcoming.

Harari, M and M Wong (2024b), “Colonial legacy and land market formality”, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania.

Harris, J R and M P Todaro (1970), “Migration, unemployment and development: A two-sector analysis”, The American Economic Review 60(1): 126-142.

Henderson, J V, T Regan and A J Venables (2020), “Building the city: From slums to a modern metropolis”, Review of Economic Studies 88(3): 1157-1192. doi:10.1093/restud/rdaa042.

Henderson, J V, D Nigmatulina and S Kriticos (2021), “Measuring urban economic density”, Journal of Urban Economics 125, article 103188. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2019.103188.

Imbert, C and G Ulyssea (2025), “Rural Migrants and Urban Informality: Evidence from Brazil”, Working Paper.

Jales, H (2018), “Estimating the effects of the minimum wage in a developing country: A density discontinuity design approach”, Journal of Applied Econometrics 33:29-51.

Jensen, A, A Brockmeyer and L Gadenne (2024), “Taxation and Development”, VoxDevLit 12(1).

Jimenez, E (1984), “Tenure security and urban squatting”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 66(4):556-567. doi:10.2307/1935979.

Joubert, C (2015), “Pension design with a large informal labor market: Evidence from Chile”, International Economic Review, 56:673-694.

Kaplan, D S, E Piedra and E Seira (2011), “Entry regulation and business start-ups: Evidence from Mexico”, Journal of Public Economics, 95:1501-1515.

Kleemans, M and J Magruder (2017), “Labour Market Responses to Immigration: Evidence from Internal Migration Driven by Weather Shocks”, Economic Journal 128(613): 2032-2065.

Kleven, H, C Landais, J Posch, A Steinhauer and J Zweimuller (2019), “Child Penalties Across Countries: Evidence and Explanations”, AEA Papers and Proceedings 109:122-126.

Kumar, T (2021), “The housing quality, income, and human capital effects of subsidized homes in urban India”, Journal of Development Economics 153: 102738. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2021.102738.

Leyva, A M (2025), “Job Flexibility”, Working Paper.

Lopez, J C L (2017), “A quantitative theory of tax evasion”, Journal of Macroeconomics 53:107-126.

Lopez-Martin, B (2018), “Informal sector misallocation”, Macroeconomic Dynamics 8:3065-3098.

Manara, V and T Regan (2022), “Ask a local: Improving the public pricing of land through local knowledge”, The Review of Economics and Statistics. doi:10.1162/rest_a_01247.

Michaels, G, et al. (2021), “Planning ahead for better neighborhoods: Long-run evidence from Tanzania”, Journal of Political Economy 129(7): 2112-2156. doi:10.1086/715940.

Meghir, C, R Narita and J M Robin (2015), “Wages and informality in developing countries”, American Economic Review 105:1509-1546.

Mills, E S (1967), “An aggregative model of resource allocation in a metropolitan area”, The American Economic Review 57(2): 197-201.

Monge-Naranjo, A, P C Ferreira and L T M Pereira (2024), “Of cities and slums”, SSRN Working Paper Series, May. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1234567.

Muth, R F (1969), Cities and Housing: The Spatial Pattern of Urban Residential Land Use, University of Chicago Press.

Naritomi, J (2018), “Consumers as tax auditors”, American Economic Review 109(9):3031-3072.

Ordonez, J C L (2014), “Tax collection, the informal sector, and productivity”, Review of Economic Dynamics 17:262-286.

Parente, M R (2024), “Minimum Wages, Inequality, and the Informal Sector”, Working Paper.

Paz, L S (2014), “The impacts of trade liberalization on informal labor markets: A theoretical and empirical evaluation of the Brazilian case”, Journal of International Economics 92:330-348.

Picarelli, N (2019), “There is no free house: The effect of a housing relocation program on labor supply and living conditions”, Journal of Urban Economics 111:35-52. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2019.04.002.

Ponczek, V and G Ulyssea (2022), “Enforcement of Labor Regulation and the Labor Market Effects of Trade: Evidence from Brazil”, The Economic Journal 132(641).

Piza, C (2018), “Out of the shadows? Revisiting the impact of the Brazilian Simples program on firms’ formalization rates”, Journal of Development Economics 134:125-132.

Rocha, R, G Ulyssea and L Rachter (2018), “Do lower taxes reduce informality? Evidence from Brazil”, Journal of Development Economics 134:28-49.

Rojas-Ampuero, F and F Carrera (2023), “Sent Away: The Long-Term Effects of Slum Clearance on Children”, Working Paper.

Samaniego de la Parra, B and L Fernández Bujanda (2024), “Increasing the cost of informal employment: Evidence from Mexico”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 16(1):377-411.

Samaniego de la Parra, B and B Sharma (2025), “How much is a formal job worth? Evidence from Mexico”, Mimeo.

Selod, H and L Tobin (2018), “The informal city”, Policy Research Working Paper 8482, The World Bank Development Research Group, Development Economics.

Sharma, G (2023), “Monopsony and Gender”, Working Paper.

Ulyssea, G (2010), “Regulation of entry, labor market institutions and the informal sector”, Journal of Development Economics 91:87-99.

Ulyssea, G (2018), “Firms, informality, and development: Theory and evidence from Brazil”, American Economic Review 108:2015-2047.

Ulyssea, G (2020), “Informality: Causes and consequences for development”, Annual Review of Economics 12:525-546.

Wong, M (2019), “Intergenerational mobility in slums: Evidence from a field survey in Jakarta”, Asian Development Review 36(1):1-19. doi:10.1162/adev_a_00121.

Zarate, R D (2024), “Spatial Misallocation, Informality and Transit Improvements: Evidence from Mexico City”, Working Paper.

Contact VoxDev

If you have questions, feedback, or would like more information about this article, please feel free to reach out to the VoxDev team. We’re here to help with any inquiries and to provide further insights on our research and content.