Firms: costs and benefits of (in)formality

This section discusses the determinants of firms’ decisions regarding the extensive and intensive margins of informality. Broadly speaking, the costs of informality can be categorised into two large groups: (i) the costs of entering the formal sector, such as the costs of formally registering a business; and (ii) the costs of remaining formal, such as tax payments and other ongoing administrative costs associated to being formal (costs associated to tax compliance beyond direct tax payments, for example). As discussed in Ulyssea (2020), if policy makers want to increase formalisation rates among firms, they can do so by reducing these costs of formality. A second approach would be to increase the benefits of formality, via greater access to capital, for example. Finally, it is possible to increase the costs of informality, which can be achieved by increasing enforcement of the existing laws and regulations (increasing the number of inspections, for example).

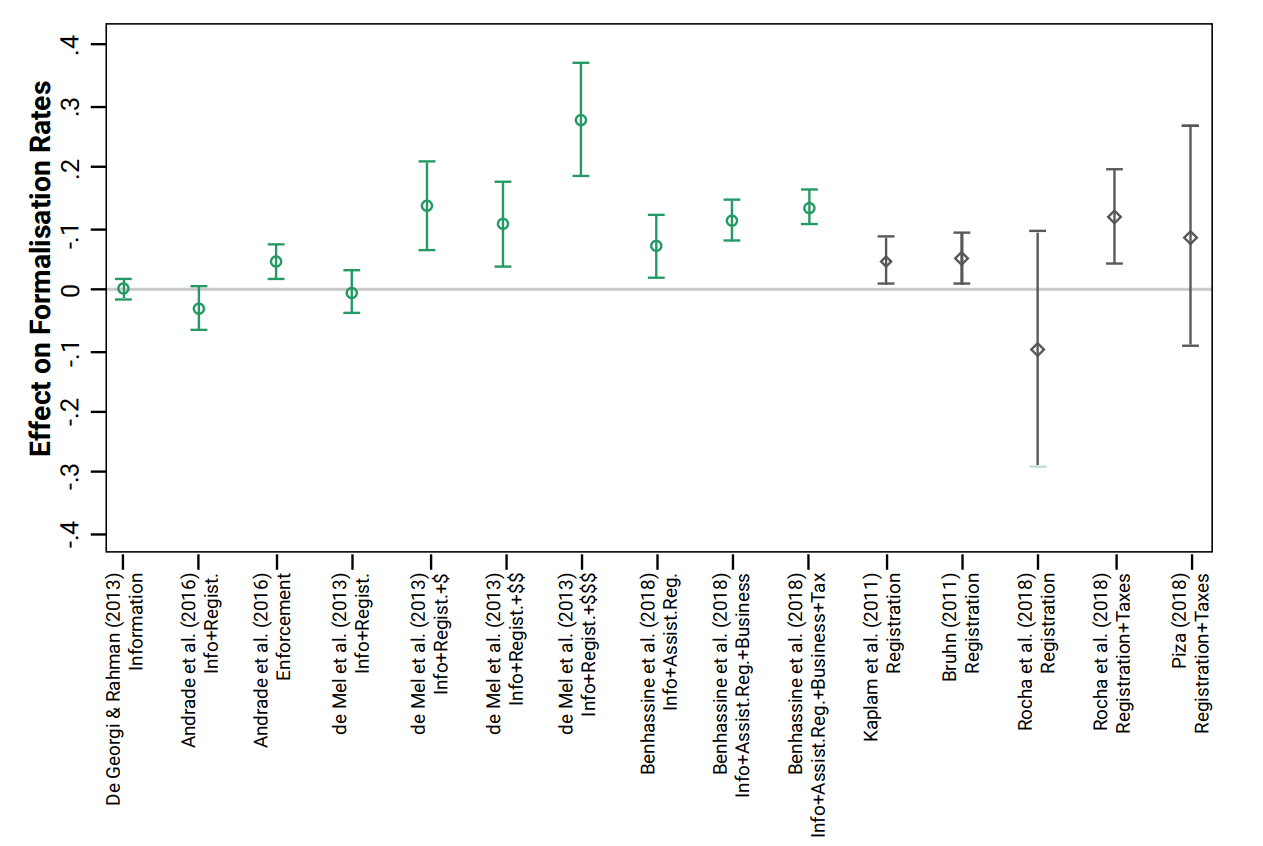

The policies or interventions analysed in papers that empirically investigate the potential determinants of firms’ formalisation decision can naturally be grouped into these three broad categories. The policies and interventions analysed in the literature have been highly concentrated in the first group – reducing the costs of formality – and in particular reducing the costs of entering the formal sector (Bruhn and McKenzie 2014). However, Figure 2 shows that the available results in the literature are not very encouraging. It summarises the results from both experimental and quasi-experimental studies that have a credible research design to identify the causal effect of a given policy.[1]

Figure 2 shows that providing information about the process of registration and its potential benefits (De Giorgi and Rahman 2013), information and reimbursing all registration costs (De Mel et al. 2013, de Andrade et al. 2016), or creating national formalisation programmes that substantially reduce registration costs (Bruhn 2011, Kaplan et al. 2011, Piza 2018, Rocha et al. 2018) have very limited effects on firm formalisation. The exception to the rule is Benhassine et al. (2018), who find a positive and significant effect of providing information and assistance in registering in Benin. However, it seems that this positive result comes from the high-quality staff used in the experiment (who were responsible for providing the information), rather than from the informational content itself. Indeed, in a follow-up intervention, the authors provided the same information without the qualified staff used in the first intervention and found no effects.

Figure 2: Formalisation effects on firms – experimental and quasi-experimental results

Notes: Figure from Ulyssea (2020). Blue circles indicate results from experimental studies and red diamonds the results from the non-experimental literature. We only report ITT estimates from the experimental papers.

Figure 2 shows that the largest formalisation effects come from interventions that reduce the costs of staying in the formal sector or that increase the benefits of formality. The results from De Mel et al. (2013) are particularly illustrative: the authors find no effects from the treatment arm that essentially eliminated registration costs; however, when firms are offered a substantial compensation for formalising (the equivalent of two months' profits for the median firm), in addition to removing registration costs, there is a substantial formalisation effect of 47%. Rocha et al. (2018) find similar results in the context of a national formalisation policy in Brazil targeted at entrepreneurs with at most one employee. In its first phase, this formalisation program eliminated entry costs for eligible entrepreneurs and in the second phase it also substantially reduced the tax burden faced by firms. The first phase had a null effect on formalisation rates, but the second one generated an increase of around 11%. This result is driven by the formalisation of existing informal firms, not by the creation of new formal businesses, nor greater survival among formal incumbents.

The third group of policies – which seek to increase the costs of informality – has received far less attention by policy makers and empirical studies. The first exception is the work of Andrade et al. (2014), who randomly assign municipal inspectors to firms to assess whether higher enforcement could induce firms to formalise in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Using an IV approach, the authors show that the impact of receiving an additional inspector visit is quite high, with an effect of 21-27 percentage points in firms’ registration. They find no spillovers to neighbouring firms.

A second important exception is the work of Samaniego de la Parra and Bujanda (2024). The authors use nearly half a million random work-site inspections by the Ministry of Labour in Mexico to analyse the effects of increasing the cost of the intensive margin of informality, that is, the cost for formal firms of hiring informal workers. At the firm level, the authors find a large negative effect on total formal employment: one year after the establishment’s first inspection, formal employment is 11% lower at inspected firms than in control firms, and this gap stabilises at a negative 15% differential and continues for 18 months after the inspection. These estimates constitute the net effect of different forces within the firms. Inspections increase both within-firm formalisation (by 6 percentage points) and separations: exit to unemployment increases for firms’ informal workers, while job-to-job transitions increase for formal employees.[2]

Interpreting the evidence

The results discussed above show that reducing the formal sector’s entry costs has very limited effects on formalisation. Reducing the ongoing costs of formality (or increasing its benefits) is more effective, but the effects are not large enough to make these policies cost effective, as they typically lead to substantial forgone tax revenues (Ulyssea 2020). Overall, the largest formalisation effects come from greater enforcement.

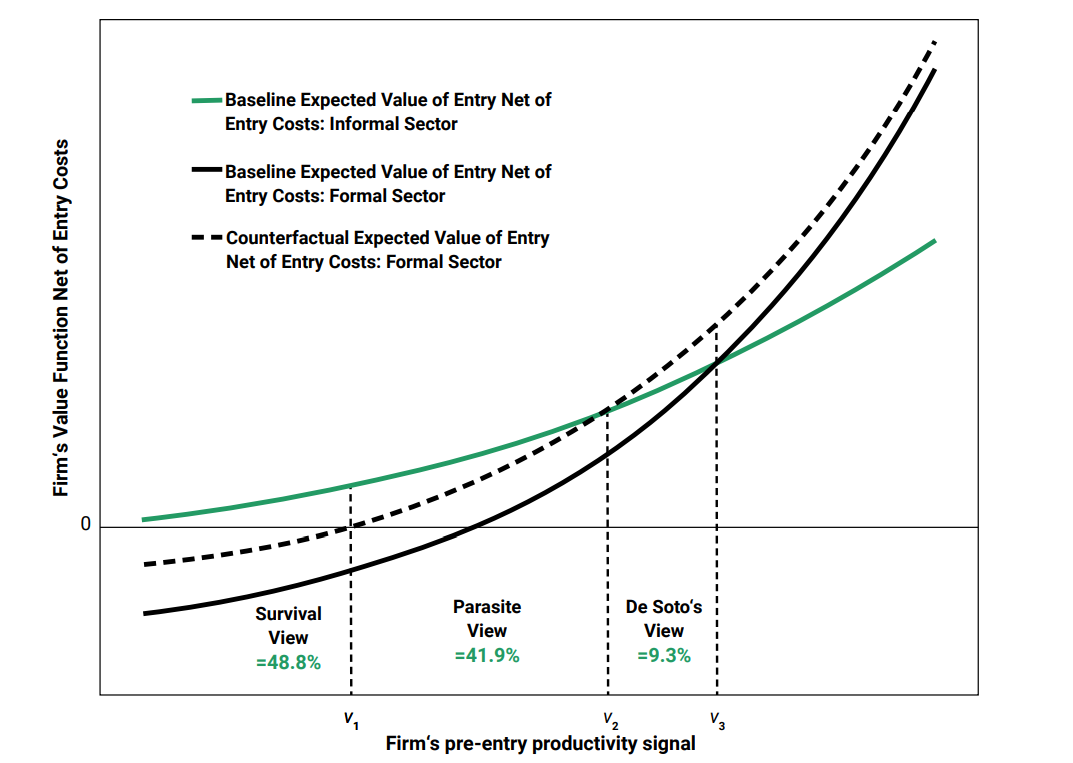

A useful way to organise these results is through the lenses of the three leading views about informality in the literature (La Porta and Shleifer 2014). The first view – the “De Soto view” – argues that the informal sector is composed of potentially productive entrepreneurs who are kept out of formality by high regulatory costs, in particular entry regulation. This view dates back to De Soto (1989) and has motivated numerous efforts to reduce fixed registration costs around the world. The second – termed the “Parasite view” – argues that informal firms are “parasite firms”: they could survive in the formal sector but choose to remain informal to earn higher profits by not complying with the relevant taxes and regulations. The third – the “Survival view” – sees informality as a survival strategy for low-skill individuals, who are too unproductive to ever become formal. The policy implications – and their expected results – are clear. According to the first view, reducing entry costs would lead to higher formality, productivity and growth, as it would “unleash” constrained informal entrepreneurs. The second view implies that the government should increase enforcement, which would allow the reallocation of resources from less productive informal firms to more productive formal ones. Finally, the third view implies that reducing entry costs would have very limited effects, while increasing enforcement would not lead to formalisation of informal firms, as they are not able to survive in the formal sector. Moreover, higher enforcement could have negative social consequences by eliminating the livelihoods of the most vulnerable individuals.

As shown in Ulyssea (2018), these views are not competing but complementary frameworks for understanding informality, as they simply reflect the underlying heterogeneity in the informal sector. Thus, the main task becomes determining their relative importance in the data. Ulyssea (2018) proposes a simple taxonomy of informal firms based on these views and uses a structural model to infer their relative importance in the Brazilian context. The results are reproduced in Figure 3.

Figure 3 shows that the “De Soto view” accounts for a small fraction of informal firms, 9.3%. The “Parasite view” corresponds to 41.9%, while the remaining 48.8% correspond to the “Survival view”. To the extent that these results from Brazil are informative for other contexts, Figure 3 provides a rationale for the results found in the empirical literature summarised in Figure 2. It is only a small fraction of informal firms that are constrained by registration costs and therefore reducing these costs does not lead to substantial formalisation. Increasing enforcement can have a substantial impact, since the parasite view encompasses a large fraction of informal firms. However, the survival view accounts for nearly half of all informal firms. Since enforcement policies cannot really distinguish between the two types of firms, they could lead to potentially large adverse effects by displacing a large number of very low productivity informal entrepreneurs and their employees. The extent to which these adverse effects would be observed in equilibrium crucially depends on how much reallocation of labour away from informal firms to more productive formal firms actually happens. Even if the reallocation does occur in the longer run, the transition to the new steady state can be costly to displaced individuals.

Figure 3: Taxonomy of informal firms in Brazil

Source: Ulyssea (2018).

How Taxes, Trade and Minimum Wages Interact with the Informal Sector

Taxes

The tax structure (and not only the tax burden) that firms face is a key determinant of their decisions to formalise, but one that has received much less attention in the literature. An early exception is the work of de Paula and Scheinkman (2010), who analyse the role of value-added tax (VAT) in transmitting informality via its credit scheme. In this type of scheme, establishments receive a credit for taxes paid upstream in the production chain, which is used against future tax liabilities. By definition, purchases from informal suppliers do not generate tax credits and informal firms cannot generate tax credits from their own suppliers, even if those are formal. Thus, formality/informality could be transmitted throughout the production chain, as more (in)formal supply chains produce greater incentives for firms to be (in)formal. The empirical analysis using micro data on formal and informal firms in Brazil confirms the predictions of their model. Formality of a firm’s suppliers and buyers is correlated with its own formal status, while greater enforcement upstream or downstream implies a higher probability of being formal. In related work, Naritomi (2018) uses a unique administrative data from Brazil to show that introducing incentives similar to the VAT for final sales leads to substantial increase in firms’ reported revenue.

This topic intertwines with the broader discussion related to taxation in developing countries, which goes beyond the scope of this review. The interested reader is referred to the excellent VoxDevLit on Taxation and Development by Senior Editor Anders Jensen and Co-Editors Anne Brockmeyer and Lucie Gadenne (Jensen et al. 2024).

Trade

Using different research designs, Paz (2014), Dix-Carneiro and Kovak (2019), Cruces et al. (2018), and Ponczek and Ulyssea (2022) find substantial effects of trade opening (tariff reduction) on informal employment. Moreover, Ponczek and Ulyssea (2022) show that these informality effects are concentrated on low-skill workers in Brazil. These results thus confirm a long-standing concern that trade reforms could lead to a reallocation of firms and workers from the formal to the informal sector due to the greater competitive pressure faced by domestic firms (Goldberg and Pavcnik 2003).

The results in Cisneros-Acevedo (2022) provide an interesting nuance to the results above and illustrate the importance of distinguishing between the two margins of informality. The author analyses the impact of import tariff reduction in Peru to show that greater trade opening had two opposing effects. On the one hand, tariff reduction leads the least productive (informal) firms to exit, which causes informality on the extensive margin to fall. On the other hand, the same competitive pressure induces formal firms to cut costs by hiring informal workers, causing an increase in the intensive margin of informality. The latter effect dominates, and overall informality increases as a result of tariff reduction.

Importantly, the results in Dix-Carneiro and Kovak (2019) and Ponczek and Ulyssea (2022) indicate that the increase in informality per se is not clearly a negative result, as informality can help reduce employment losses after a negative shock. In particular, Ponczek and Ulyssea (2022) show that regions with weaker enforcement observed higher informality effects but no unemployment effects. Not only that, in these regions formal plants had a larger probability of surviving, most likely due to the intensive margin (which is consistent with the results of Cisneros-Acevedo 2022).

The flipside of these more negative results can be found in the work of McCaig and Pavcnik (2018). They show that a positive export shock in Vietnam (from the U.S.-Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement) led to a substantial decline of informality due to the reallocation of workers away from informal firms to more productive formal firms.

Despite their importance, these empirical studies are not able to account for general equilibrium effects, which can be quite important in the case of trade opening. Dix-Carneiro et al. (2024) develop an equilibrium trade model with firm dynamics and firm heterogeneity, formal and informal sectors, labour market frictions and a rich institutional setting, which is estimated using several data sources from Brazil. Their results are broadly consistent with those from the empirical literature discussed thus far, whereby the decline in informality within the tradable sector is a consequence of trade liberalisation. However, the authors show that even though informality can be an “unemployment buffer” – as shown by Ponczek and Ulyssea (2022) – it is not a “welfare buffer”, as welfare is actually higher when enforcement is stronger, even if it comes at the cost of greater unemployment.

Minimum Wage

The analysis of labour market effects of the minimum wage is one of the oldest and most contentious topics in labour economics. A full review of this literature is outside the scope of this article and the reader is referred to the many excellent reviews available in the literature (for the most recent one, see Dube and Lindner 2024). Instead, we focus on recent work that analyses the effects of minimum wage increases on informality, which mostly focus on Brazil, a high informality country that increased its national minimum wage by 130% in real terms between 1996 and 2018.

The results from this recent body of literature present an inconclusive picture. Jales (2018) uses a density discontinuity design to show that informality would be much lower in Brazil in the absence of the minimum wage. Most studies, however, leverage the substantial increase in the Brazilian national minimum wage and cross-regional variation in wage levels (i.e. how binding the national minimum wage is in the baseline period) to identify its effects. Despite the methodological similarities, they reach quite different conclusions. Parente (2024) finds an increase in informal employment relative to formal employment, while Derenoncourt et al. (2021) and Engbom and Moser (2022) estimate zero effects on informality.

Haanwinckel (2024) argues that the reason for such discrepancy across studies is the fact that these estimators are prone to biases from correlated measurement errors and functional form misspecification. He shows that these estimators can be plagued by economically significant biases when used in contexts with a national minimum wage (as in Brazil).

Consistent with the more pessimistic results about minimum wage effects, Haanwinckel and Soares (2021) use an equilibrium structural model to show that the observed decline in both informality and unemployment in the 2000’s would have been considerably larger - 2.3 and 2.9 percentage points, respectively - if the minimum wage had not increased during this period. This is consistent with the counterfactual results in Parente (2024), which show that minimum wage increases lead to higher informality, an increase in wage inequality within the informal sector and an increase in overall inequality, despite the inequality-reducing effect within the formal sector.

Why are Workers in the Informal Sector?

The Role of Public Policies

One important concern in developing countries with large informal sectors is the potential effect of welfare policies shifting labour supply from the formal to the informal sector. This is clearly a concern in cash transfer programmes that are means-tested, which could incentivise individuals to work informally to remain eligible for the benefit. More broadly, universal programmes that increase the benefits of informality (or reduce its costs) could produce similar effects, as extensively discussed in Levy (2010).

Bosch and Campos-Vazquez (2014) analyse one such programme, the Seguro Popular in Mexico. It was created in 2002 and introduced universal health coverage, including all informal and previously uninsured informal workers. Before that, health coverage was tied to payroll contributions, which represented a large cost of being informally employed. Hence, the programme substantially decreased the costs of informality. The authors show that Seguro Popular had a negative effect on the formality trend (measured by social security contribution) in small and medium firms. In the absence of the programme, around 4.6 and 4% additional employers and employees would have formally registered, respectively.[3] Camacho et al. (2013) analyse a similar programme in Colombia (the Subsidised Health Regime) and find that the programme leads to an increase in informal employment of around 4 percentage points. The reported effects are not very large, which could indicate that the value of these programmes to workers is not very high. Indeed, Conti et al. (2018) develop and estimate a household search model with formal and informal sectors and show that the utility value of Seguro Popular represents 4% and 9% of the mean household income for high and low education households, respectively.

As discussed above, the availability of cash transfer programmes could also be an important determinant of informal labour supply and could discourage work more broadly (Banerjee et al. 2017). Evidence from the Bolsa Família in Brazil (De Brauw et al. 2015), Plan de Atención Nacional a la Emergencia Social in Uruguay (Bergolo and Cruces 2021), and the Universal Child Allowance in Argentina (Garganta and Gasparini 2015) suggest that both of these effects – higher informality and non-employment – are present in the data. For example, Bergolo and Cruces (2021) find a reduction of formal employment in eligible households of around 8 percentage points, which are equally distributed between informal employment and non-employment. More recently, however, Leite Mariante (2025) shows that an exogenous increase in Brazil’s Bolsa Família had no effect on men, and increased women’s formal employment by 7.4% over two years. This effect is driven by mothers, for whom the transfer relaxes childcare constraints.

These results refer to the direct effects of the transfer on individuals’ labour supply decisions. However, some of these programs are quite large in scale and could have sizable general equilibrium effects in local economies. Indeed, Gerard et al. (2024) show in recent work that Bolsa Família (PBF) led to an increase in local formal employment in Brazil. They exploit a large increase in the number of PBF beneficiaries in 2009, as well as a change in the methodology used to allocate slots across municipalities. Their main result indicates that municipalities more positively affected by the increase in total PBF payments observed an increase in the number of formal jobs of up to 2% by 2011 (two years after the reform). The effects are concentrated in low-skill, private sector jobs with no effects on public sector jobs. Their results suggest that larger PBF benefits had an important local multiplier effect, as they also find a similar increase in formal employment for workers who were never part of the programme.

The discussion thus far has focused on the static relationship between public policies and individuals’ informality decisions. However, there can be important dynamic implications as well, especially when one considers the effects of social security systems that have some form of non-contributory safety net that provides a minimum benefit to the elderly. These non-contributory benefits can represent a tax on individuals who contribute, as they are typically decreasing in one’s contributions, and could hence discourage formal work, especially for low skill workers. Joubert (2015) investigates the importance of these forces in a life-cycle, discrete choice model that captures household's labour supply choice between formal and informal employment, and saving decisions under the rules of Chile's pension system. The results from counterfactual analysis using the estimated model show increasing the mandatory contribution rate by 5 percentage points increases informality by 12.5% and 9.3% for men and women, respectively.[4]

Finamor (2024) extends the existing literature by developing a life-cycle model of labour supply, formal/ informal employment, and savings with search frictions. An important implication of his analysis is that workers have a high willingness to pay (WTP) for a formal job: on average, an informal employee would forgo 18.7% of their earnings to have their job “formalised”. His decomposition exercise further shows that 62% of this value is due to higher stability and better job search prospects, while 38% is due to the insurance package offered by formal jobs. This estimated value of a formal job is of similar magnitude of that obtained by Samaniego de la Parra and Sharma (2025): they estimate this value to between 14% and 20% of the median monthly wage in Mexico.

Workers: The role of human capital

As discussed in Section 3, a well-established fact about informality is that it is (sometimes sharply) decreasing with individuals’ schooling levels. This fact could thus suggest that changes in the composition of the labour force toward a higher share of more-educated workers could be an important force to reduce informality rates. This seems consistent with broad trends observed in many Latin American countries, which have recently shown sustained reductions in informality among employees, without experiencing major changes in labour regulations, minimum wages, or enforcement.

A recent study by Haanwinckel and Soares (2021) investigates to what extent the changes in composition of the labour force could explain the observed strong reduction in informality levels observed in Brazil in the 2000s. For this, the authors develop a model with two types of workers—skilled and unskilled—and a large number of firms, which differ in productivity but are not intrinsically connected to any sector. Decisions related to formality status are the result of a labour market equilibrium where each agent is choosing optimally. The model incorporates many features of Brazilian labour regulation: payroll taxes, mandated benefits, and the minimum wage. Finally, it also includes an informality penalty that increases with firm size to account for the risk of being caught by labour inspectors and for the eventual punishment. The model is able to reproduce several patterns in the Brazilian labour market, especially those related to labour informality, even though it does not impose structural differences across sectors.

Their key result is that increased schooling is the most important factor in explaining the decline in informality observed in Brazil between 2003 and 2012. If the schooling composition of the labour force had remained the same as in 2003, but all other factors had changed according to what was observed during the period, there would have been an increase in the informality rate instead of a large decrease. In the model, increased schooling alone can generate a large decline in informality rates, suggesting that education is a key determinant of formalisation. Two main channels explain this result. First, an expansion in schooling levels leads to higher low-skill wages due to scarcity and increased productivity of these workers, which results in higher wages in the informal sector. Second, it stimulates increases in firm size. As a result of the increased incentive to grow, formal firms hire more workers and, simultaneously, firms operating at the margin of informality find it profitable to move into the formal sector (since it is difficult to hide in the informal sector if a firm becomes too large).

Fertility and Informality

As discussed in Section 2, women are over-represented in informal jobs. Even though formal contracts in developing countries are more stable and on average offer higher wages, they are typically very rigid in terms of working hours and work arrangements – e.g. there are limited part-time opportunities. Given that women are disproportionally burdened with household and childcare responsibilities, informal jobs may be an attractive option because of the higher flexibility they offer (Berniell et al. 2021). Moreover, informal jobs are also less spatially concentrated than formal ones and often allow low-skill workers to work from home, thus being associated to substantially lower commuting times (Zarate 2024).

Berniell et al. (2021) use Chilean data to show that motherhood explains a large part of the gender gap in informality rates observed in Chile. Similarly to the child penalty literature that focuses on developed economies (e.g. Kleven et al. 2019), the authors show that the birth of the first child has substantial and long-lasting effects on labour market outcomes of mothers, while fathers remain unaffected. In particular, they show that the fall in female employment is explained by a reduction in formal employment, with a 38% increase in the informality rate among women and no effects on men. These results are corroborated by Leyva (2025), who analyses the impacts of childbirth and the loss of childcare support on women’s employment outcomes in Mexico. In both events, mothers are more likely to transition to informal employment and to reduce hours worked within the informal sector.

Given these results, there remains the question of whether having access to informal jobs makes women better or worse off in the short- and long-run relative to a counterfactual scenario with, say, stronger enforcement and lower informality. On the one hand, informal jobs could make it less costly for women to remain attached to the labour market after having children, thus improving employment outcomes in the short run. On the other hand, if long spells in the informal sector make it harder to transit back to the formal sector, and if the latter offers higher life-cycle wage gains, then taking up informal jobs would lead to long-run losses for women. Thus, women might face an intertemporal trade-off associated to taking up informal jobs after having children.

Migration and the Informal Sector

The analysis of the relationship between migration – in particular rural-urban migration – and informality dates back to the seminal works of Harris and Todaro (1970) and Fields (1975). The “Harris-Todaro-Fields” framework predicts that immigration has negative labour market effects in urban destinations, as migrants join the pool of unemployed or informal workers. Albeit highly stylised this framework remains very influential, no less because its predictions have been confirmed by empirical evidence on the short-run effects of ruralurban migration. This literature estimates year-on-year effects of inflows of rural migrants on urban labour markets, showing that greater immigration leads to employment losses in the formal sector with limited effects on wages, while negative effects on informal sector wages are large but with lower employment losses (El Badaoui et al. 2017, Kleemans and Magruder 2017, Corbi et al. 2024). The interpretation of these results is best summarised by Kleemans and Magruder (2017): “…we propose that this result may be understood as another consequence of the two-sector labour market with a wage floor in the formal sector where the lessskilled group faces chances of disemployment or employment in the informal sector”.

These predictions are also confirmed by a recent literature that analyses the short-run economic effects of refugees on labour market outcomes of receiving developing countries. Altındağ et al. (2020), for example, show that Turkish firms located in regions that receive Syrian refugees benefit from these inflows, but these positive effects are concentrated in the informal economy. More recently, Delgado-Prieto (2024) shows that the arrival of Venezuelan refugees in Colombia leads to a strong decline in wages in the informal sector but with limited decline in employment, while in the formal sector there are no effects on wages but stronger negative effects on employment. Thus, these results are very much in line with the rural-urban migration literature, in particular with the results in Kleemans and Magruder (2017) and Corbi et al. (2024).[5]

More recently, Imbert and Ulyssea (2025) investigate the long-run economic effects of rural-urban migration on local urban economies in Brazil. In sharp contrast with the previous literature, they show that droughtinduced immigration reduces informality, has no effect on unemployment, and increases the number of formal firms and jobs over a decade. Although these results are seemingly at odds with predictions from the “Harris-Todaro-Fields” framework, the authors show that these effects are weaker in municipalities where formal sector wages exhibited greater downward nominal wage rigidity (DNWR) at baseline. In the short run, when wage rigidity is strongest, they obtain the same results as in the previous literature – i.e. cities that receive more rural migrants experience an increase in informality. These results highlight the contrast between the short- and long-run labour market effects of migration. Moreover, their reduced form evidence, combined with the model-based counterfactuals, consistently shows that sluggish wage adjustment in the formal sector can explain these differences between short- and long-run effects.

Determinants of Slum Formation and Growth

The earliest literature on slums emphasised the role of rapid rural-to-urban migration (Harris and Todaro 1970), characterising slums as a transitory phenomenon typical of economies undergoing structural transformation (Frankenhoff 1967). Monge Naranjo et al. (2024) provide a more recent take on slum formation and structural transformation through the lens of a dynamic macro model.

Subsequent research on the role of slums in urban development has highlighted the duality of housing markets, formal and informal. One strand of literature embeds residents’ choices of whether to squat (subject to eviction risk) or rent in the formal market into the classic monocentric city model (Alonso 1964, Mills 1967, Muth 1969). For example, in Brueckner and Selod (2009), squatters and formal households compete for land and there is no eviction in equilibrium. Squatting emerges as an equilibrium outcome when regulation (e.g. minimum lot sizes) forces the poor out of the formal market (Jimenez 1984) or when formal property titles are costly to obtain (Selod and Tobin 2018).

More recently, Alves (2021) embeds the choice of formal versus informal land tenure in a system-of-cities model and estimates separate housing elasticities for the formal and informal sectors in Brazil, showing that faster rent growth in the formal sector forces low-income migrants into slums. In Cavalcanti et al.’s (2019)’s single-city model, slum residents trade off foregone labour income (as they need to be at home to protect it from eviction) and the cost of complying with regulation in the formal market.

Henderson et al. (2020) focus on supply-side dynamics. They theoretically and empirically analyse the dynamics of land use in Nairobi, Kenya, documenting transitions of slums to high-rise formal neighbourhoods. The model characterises the timing of these transitions as a function of the evolution of formal land values. The authors highlight the role of spatially heterogeneous formalisation costs in delaying the redevelopment of slums, resulting in potential land misallocation.

Beyond these contributions, several empirical papers have examined other determinants of slum formation in cities, including historical land market institutions and legal origin (Harari and Wong 2024b, Fredriksson et al. 2023), strategic behaviour of mayors in withholding public goods provision (Feler and Henderson 2011), and rapid immigration (Gonzalez Navarro and Undurraga 2023).

References

Alonso, W (1964), Location and Land Use: Toward a General Theory of Land Rent, Harvard University Press, Reprint 2013. doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674730854.

Altındağ, O., Bakış, O., & Rozo, S. V. (2020). Blessing or burden? Impacts of refugees on businesses and the informal economy. Journal of Development Economics, 146, 102490.

Alves, G (2021), “Slum growth in Brazilian cities,” Journal of Urban Economics 122, article 103327. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2021.103327.

Banerjee, A V, R Hanna, G E Kreindler and B A Olken (2017), “Debunking the stereotype of the lazy welfare recipient: Evidence from cash transfer programs”, The World Bank Research Observer, 32:155–184.

Benhassine, N, D McKenzie, V Pouliquen and M Santini (2018), “Does inducing informal firms to formalize make sense? experimental evidence from Benin”, Journal of Public Economics, 157:1–14.

Bergolo, M and G Cruces (2021), “The anatomy of behavioral responses to social assistance when informal employment is high”, Journal of Public Economics, 193: 104313.

Bruhn, M (2011), “License to Sell: The Effect of Business Registration Reform on Entrepreneurial Activity iin Mexico.” Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(1): 382-386.

Bruhn, M and D McKenzie (2014), “Entry regulation and the formalization of microenterprises in developing countries”, The World Bank Research Observer, 29:186–201.

Brueckner, J K, and H Selod (2009), “A theory of urban squatting and land-tenure formalization in developing countries,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 1(1): 28–51. doi:10.1257/pol.1.1.28.

Camacho, A, E Conover and A Hoyos (2013), “Effects of Colombia’s social protection system on workers’ choice between formal and informal employment”, The World Bank Economic Review 28:446–466.

Cavalcanti, T, D Da Mata, and M Santos (2019), “On the determinants of slum formation,” The Economic Journal 129: 1971–1991. doi:10.1111/ecoj.12626.

Cisneros-Acevedo, C (2022), “Unfolding trade effect in two margins of informality: The Peruvian case”, The World Bank Economic Review, 36: 141–170.

Conti, G, R Ginja and R Narita (2018), “The value of health insurance: A household job search approach”, IZA DP, 11706.

Corbi, R, T Ferraz, R Narita (2024), “Internal migration and labor market adjustments in the presence of non-wage compensation”, Working Paper.

Cruces, G, G Porto and M Viollaz (2018), “Trade liberalization and informality in Argentina: exploring the adjustment mechanisms”, Latin American Economic Review, 27:1-29.

de Andrade, G H, M Bruhn, D Mckenzie (2016), “A Helping Hand or the Long Arm of the Law? Experimental Evidence on What Governments Can Do to Formalize Firms”, The World Bank Economic Review, 30(1):24-54.

De Brauw, A, D O Gilligan, J Hoddinott and S Roy (2015), “Bolsa Familia and household labor supply”, Economic Development and Cultural Change, 63:423-457.

De Giorgi, G and A Rahman (2013), “SME’s registration: Evidence from an RCT in Bangladesh”, Economics Letters, 120:573 – 578.

De Mel, S, D McKenzie and C Woodruff (2013), “The demand for, and consequences of, formalization among informal firms in Sri Lanka”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 5:122-50.

De Paula, A and J A Scheinkman (2010), “Value-added taxes, chain effects, and informality”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 2:195-221.

Delgado-Prieto, L. (2024). Immigration, wages, and employment under informal labor markets. Journal of Population Economics, 37(2), 55.

Derenoncourt, E, F Gérard, L Lagos, and C Montialoux (2021), “Racial Inequality, Minimum Wage Spillovers, and the Informal Sector”, Working Paper.

De Soto, H (1989), The Other Path, Harper Row: New York.

Dix-Carneiro, R and B K Kovak (2019), “Margins of labor market adjustment to trade”, Journal of International Economics, 117:125-142.

Dix-Carneiro, R, P K Goldberg, C Meghir and G Ulyssea (2024), “Trade and Domestic Distortions: The Case of Informality”, NBER Working Paper 28391.

Dube, A and A S Lindner (2024), “Minimum Wages in the 21st Century”, Working Paper.

El Badaoui, E, E Strobl and F Walsh (2017), “Impact of internal migration on labor market outcomes of native males in Thailand”, Economic Development and Cultural Change 66(1): 147-177.

Engbom, N and C Moser (2022), “Earnings Inequality and the Minimum Wage: Evidence from Brazil”, American Economic Review 112(12): 3803-47.

Feler, L., and J. V. Henderson (2011). “Exclusionary policies in urban development: Under-servicing migrant households in Brazilian cities.” Journal of Urban Economics 69(3): 253–272. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2010.09.006.

Finamor, L. (2024). Labor market informality, risk, and insurance. Mimeo.

Fredriksson, P G, S K Gupta, W Zhao, and J R Wollscheid (2023), “Legal heritage and urban slums,” Journal of Regional Science 63(1): 236–252. doi:10.1111/jors.12622.

Frankenhoff, C A (1967), “Elements of an economic model for slums in a developing economy,” Economic Development and Cultural Change 15(1): 27–35. doi:10.1086/450204.

Garganta, S and L Gasparini (2015), “The impact of a social program on labor informality: The case of AUH in Argentina”, Journal of Development Economics, 115(C):99-110.

Gerard, F, J Naritomi and J Silva (2024), “Cash Transfers and the Local Economy: Evidence from Brazil”, Working Paper.

Goldberg, P K and N Pavcnik (2003), “The response of the informal sector to trade liberalization”, Journal of Development Economics, 72:463-496.

Gonzalez-Navarro, M, and R Undurraga (2023), “Immigration and slums,” Working Paper.

Haanwinckel, D. (2024). Does regional variation in wage levels identify the effects of a national minimum wage? Mimeo.

Haanwinckel, D and R R Soares (2021), “Workforce composition, productivity, and labor regulations in a compensating differentials theory of informality”, The Review of Economic Studies, 88:2970-3010.

Harari, M, and M Wong (2024b), “Colonial legacy and land market formality,” The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania.

Harris, J R., & M P Todaro (1970). Migration, unemployment and development: a two-sector analysis. The American Economic Review, 60(1), 126-142.

Henderson, J V, T Regan, and A J Venables (2020), “Building the city: From slums to a modern metropolis,” Review of Economic Studies 88(3): 1157-1192. doi:10.1093/restud/rdaa042.

Imbert, C and G Ulyssea (2025), “Rural Migrants and Urban Informality: Evidence from Brazil”, Working Paper.

Jales, H. (2018). Estimating the effects of the minimum wage in a developing country: A density discontinuity design approach. Journal of Applied Econometrics 33: 29-51.

Jensen, A, A Brockmeyer, and L Gadenne, “Taxation and Development” VoxDevLit, 12(1), September 2024.

Jimenez, E (1984), “Tenure security and urban squatting,” The Review of Economics and Statistics 66(4): 556-567. doi:10.2307/1935979.

Joubert, C (2015), “Pension design with a large informal labor market: Evidence from Chile”, International Economic Review, 56:673-694.

Kaplan, D S, E Piedra and E Seira (2011), “Entry regulation and business start-ups: Evidence from Mexico”, Journal of Public Economics, 95:1501-1515.

Kleemans, M and J Magruder (2017), “Labour Market Responses to Immigration: Evidence from Internal Migration Driven by Weather Shocks”, Economic Journal 128(613): 2032-2065.

Kleven, H, C Landais, J Posch, A Steinhauer and J Zweimuller, “Child Penalities Across Countries: Evidence and Explanations”, AEA Papers & Proceedings 109: 122-126.

Kuffer, M, K Pfeffer, and R Sliuzas (2016), “Slums from space—15 years of slum mapping using remote sensing,” Remote Sensing 8(6), article 455. doi:10.3390/rs8060455.

La Porta, R and A Shleifer (2014), “Informality and development”, The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28:109-126.

Leite Mariante, G (2025), “Cash transfers and women's labour supply: evidence from the world's largest programme”, Working Paper.

Leyva, A M (2025), “Job Flexibility”, Working Paper.

McCaig, B and N Pavcnik (2018), “Export markets and labor allocation in a low-income country”, American Economic Review, 108:1899-1941.

Mills, E S (1967), “An aggregative model of resource allocation in a metropolitan area,” The American Economic Review 57(2): 197-201.

Monge-Naranjo, A, P Cavalcanti Ferreira, and L T M Pereira (2024), “Of cities and slums,” SSRN Working Paper Series, May. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1234567.

Muth, R F (1969), Cities and housing: The spatial pattern of urban residential land use, University of Chicago Press.

Naritomi, J (2018), “Consumers as tax auditors”, American Economic Review, 109(9):3031-3072.

Parente, M R (2024), “Minimum Wages, Inequality, and the Informal Sector”, Working Paper.

Paz, L S (2014), “The impacts of trade liberalization on informal labor markets: A theoretical and empirical evaluation of the Brazilian case”, Journal of International Economics, 92:330-348.

Ponczek, V and G Ulyssea (2022), “Enforcement of Labor Regulation and the Labor Market Effects of Trade: Evidence from Brazil”, The Economic Journal, 132(641).

Piza, C (2018), “Out of the shadows? Revisiting the impact of the Brazilian Simples program on firms’ formalization rates”, Journal of Development Economics, 134:125-132.

Rocha, R, G Ulyssea and L Rachter (2018), “Do lower taxes reduce informality? evidence from Brazil”, Journal of Development Economics, 134:28-49.

Samaniego de la Parra, B., and L. Fernández Bujanda (2024). Increasing the cost of informal employment: Evidence from Mexico. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 16(1), 377-411.

Samaniego de la Parra, B. and B. Sharma (2025). How much is a formal job worth? Evidence from Mexico. Mimeo.

Selod, H, and L Tobin (2018), “The informal city,” Policy Research Working Paper 8482, The World Bank Development Research Group, Development Economics, June.

Ulyssea, G (2018), “Firms, informality, and development: Theory and evidence from Brazil”, American Economic Review, 108:2015-47.

Ulyssea, G (2020), “Informality: Causes and consequences for development”, Annual Review of Economics, 12:525-546.

Zarate, R D (2024), “Spatial Misallocation, Informality and Transit Improvements: Evidence from Mexico City”, Working Paper.

Contact VoxDev

If you have questions, feedback, or would like more information about this article, please feel free to reach out to the VoxDev team. We’re here to help with any inquiries and to provide further insights on our research and content.