Carbon offset programmes allow polluters to pay others to reduce emissions on their behalf. In theory, this can achieve the same emissions reductions at a lower cost, but only if the payment actually incentivises the recipient to cut emissions. If offsets fund projects that would have happened without the subsidy, there are no real emissions reductions, and selling the offset could then lead to a net increase in emissions. Our research on India’s wind sector highlights significant misallocation in the world’s largest offset programme, raising concerns about the effectiveness of carbon offset initiatives.

Carbon offsets and the concept of ‘additionality’

Carbon offsets have become a popular tool in global efforts to mitigate climate change. These programmes work by offering regulated polluters the opportunity to increase their own emissions if they subsidise equivalent emission reductions in unregulated markets. The world’s largest carbon offset programme—the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM)—has supported more than US$90 billion of renewable energy investments in developing countries, equivalent to 13% of their total renewable energy investments (Kossoy et al. 2015).

But do these carbon offsets result in ‘additional’ emissions reductions in unregulated markets? If carbon offsets are awarded to projects that would have been developed without the subsidy, they do not represent emissions savings globally. This results in an inefficient allocation of scarce climate change mitigation resources and ultimately leads to higher global emissions than if firms were not allowed to use offsets for compliance.

Our new research (Calel et al. 2025) develops a method for identifying inframarginal projects based on observable characteristics, and with it we uncover evidence of significant CDM offset misallocation in India’s wind power sector.

Studying the prevalence of ‘Blatantly Inframarginal Projects’

To ensure climate benefits, offset programmes must accurately identify and subsidise marginal projects—projects that are made viable because of the subsidy. A critical measure of success, then, is a programme’s ability to screen out any projects that would have been developed anyway.

Our approach identifies a subset of all inframarginal projects (i.e. those projects that would have happened without a subsidy), which we refer to as Blatantly Inframarginal Projects (BLIMPs). BLIMPs are not just inframarginal, but blatantly so, in the sense that they appear strictly more profitable ex ante than other projects that were built without subsidies. We argue that, conditional on being built in the same state and year, a subsidised wind farm is clearly better than an unsubsidised farm if it has a higher capacity, is built in a windier location, and is built closer to a connection point. The number of BLIMPs provides a lower bound on the number of non-additional projects.

The allocation of subsidies under the Clean Development Mechanism has been inefficient

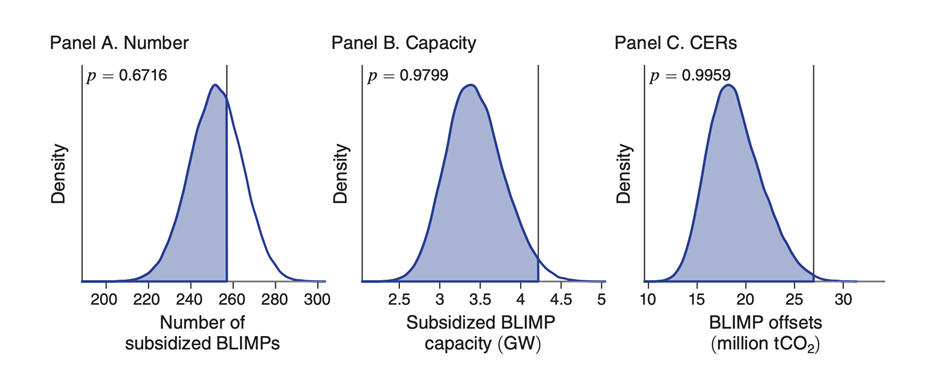

The Indian wind power sector was identified early on as a promising context for the CDM to perform well, given its high upfront capital costs and limited early-stage development. However, our analysis of 1,346 wind farms constructed between 1992 and 2013 tells a different story (Figure 1):

- We identify 257 out of the 476 CDM-registered Indian wind farms in our data as BLIMPs, accounting for roughly 52% of carbon offsets approved for Indian wind projects. For each of these 257 projects, we can point to at least one unsubsidised wind farm built in the same state and year that appears to be strictly less profitable.

- The CDM has approved at least 27 million tonnes worth of carbon offsets to BLIMPs in the Indian wind power sector. If this figure is extrapolated to the CDM as a whole, it would mean the programme has enabled regulated polluters to emit an additional 6.1 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide. This is equivalent to running 1,500 typical coal-fired power plants for a year.

- The discounted social losses associated with these emissions would be valued at $1.2 trillion ($2020).

Even in a setting where the CDM was expected to perform well, we find that a substantial share of subsidies has been allocated to projects that would have very likely been built anyway. This misallocation represents a significant inefficiency, critically undermining the offset mechanism.

Figure 1: Number, capacity, and quantity of certified emission reductions approved for BLIMPs

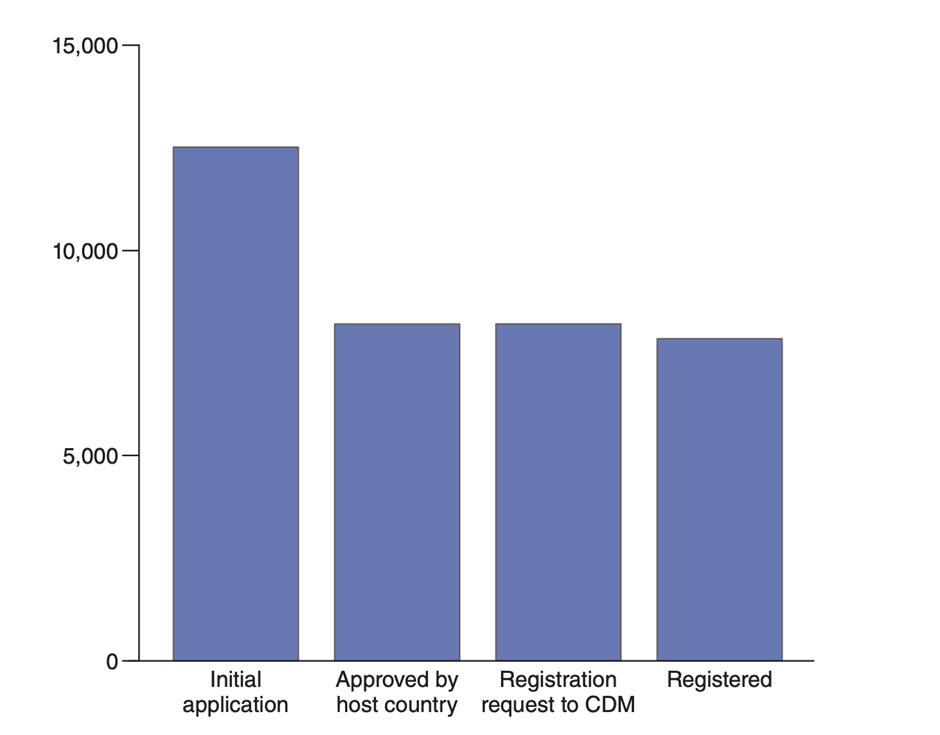

How did the Clean Development Mechanism subsidies compare to random allocation?

To better understand the scale of misallocation, we compared the CDM’s decisions to a simple benchmark: random allocation. We randomly selected different subsets of the population of wind farms to be awarded CDM credits, noting that, in expectation, a lottery would allocate subsidies in a way that is uncorrelated with whether a project is marginal or inframarginal.

The CDM appears to have performed poorly relative to the allocations that a lottery mechanism may have produced. When choosing projects at random from the whole population of Indian wind farms, two out of every three draws would have registered fewer BLIMPs than the CDM did. This unfavourable comparison with a lottery indicates that there is substantial room for improvement in the design and implementation of the project selection mechanism.

Figure 2: Comparing the number, capacity, and quantity of carbon emission reductions to a lottery

Institutional failures explaining the Clean Development Mechanism misallocation

Why, then, is the CDM favouring the more profitable projects to such a degree? Our analysis identifies a series of institutional failures.

Firstly, the project must be approved by the Designated National Authority, whose main task is to assess whether the project will help the host country achieve its sustainable development goals. Yet, diplomatic cables released by WikiLeaks in 2011 revealed that the Indian National Authority makes no independent assessment of whether a project is marginal or inframarginal and that the CDM Executive Board is aware of this.

Third-party independent verifiers are then meant to assess the additionality of the project. These contractors, however, are selected and paid by the project developers, creating a strong incentive to approve or coach the projects into approval (Duflo et al. 2013). In practice, verifiers sign off on and request registration for practically all host approved applications.

The final opportunity to separate inframarginal from marginal projects is when the 10-member CDM Executive Board considers each registration request. This Board is likely severely constrained in its ability to reject requests due to its limited time and resources to independently analyse complex financial and technical information. Further, the board members may struggle to resist political pressures from host countries and offset buyers. Consequently, the CDM Executive Board approved over 95% of these requests.

The combined effect of these institutional failures is an almost automatic approval based on whether the host country approves the application in the first stage (Figure 3). In this context, Indian authorities explicitly aim to maximise contributions to its sustainable development goals, which often results in supporting larger wind projects in better locations. Yet, these are precisely the projects that are more profitable ex ante. This would explain our finding that the CDM supported even more BLIMPs than would have been supported through a lottery.

Figure 3: Number of CDM applications at each stage

Do carbon offsets offset carbon?

Our results pose a serious challenge to claims that the CDM is successfully offsetting emissions. Carbon offsets are frequently given to BLIMPs, which means that they do not generate the additional emissions reductions needed to offset the emissions increases that they enable. Our research in India’s wind power sector illustrates that there is a significant misallocation of resources even for the type of projects that the CDM was made to support.

References

Calel, R, J Colmer, A Dechezleprêtre, and M Glachant (2025), “Do carbon offsets offset carbon?” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 17(1): 1–40.

Duflo, E, M Greenstone, R Pande, and N Ryan (2013), “Truth-telling by third-party auditors and the response of polluting firms: Experimental evidence from India,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(4): 1499–1545.

Kossoy, A, G Peszko, K Oppermann, N Prytz, N Klein, K Blok, L Lam, et al. (2015), "State and trends of carbon pricing 2015," World Bank.