The US, China, and the EU are shaping the future of climate policy, but could their efforts hurt trade opportunities for developing countries? How should policymakers balance the green benefits of climate policy against the economic risks for those in low- and middle-income countries?

Editor’s note: You can read more about the link between trade policy and the environment in our VoxDevLit on International Trade.

The connection between trade and climate efforts is gaining increasing attention, particularly in the context of using trade policy as a tool for achieving climate goals. For instance, removing tariff biases favouring emission-intensive goods has been found to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and trade agreements have helped address deforestation. However, there is less focus on how climate-related trade policies affect the development and green transition in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

The world’s three largest economies—China, EU, and US—are intensifying their efforts to address the threat of climate change through green subsidies, carbon pricing, and sector-specific regulations. While these climate-focused initiatives are necessary, they will directly impact trade, creating both risks and opportunities for exporters. The existing research on the impacts of climate regulations focuses largely on select advanced economies (Attinasi et al. 2023, Kleimann et al. 2023, Gründler 2023), overlooking the implications of these policies on developing countries.

How do climate policies impact trade in developing countries?

A new World Bank study aims to bridge this gap by analysing how climate policies introduced by China, the EU, and the US impact developing countries, outlining strategies to mitigate negative effects and leverage new export opportunities (Aldaz-Carroll et al. 2024). This analysis underscores the importance of complementing climate action with development assistance to ensure an inclusive green transition, especially for those in the Global South.

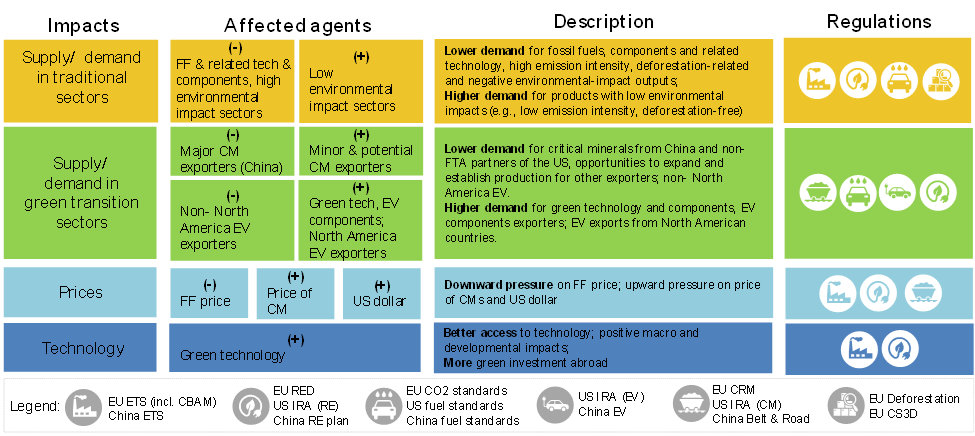

The future of trade in developing countries will likely be shaped by the climate policies of their trade partners (Figure 1). The demand for fossil fuels and related technologies is likely to fall following efforts to curb GHG emissions, such as the European Green Deal, US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)[1], and China’s Emissions Trading System. Emission-intensive exports will also be affected by the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism and Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive, and many agricultural good exports will be constrained by the EU Regulation on Deforestation-free products (EUDR).

Moreover, critical mineral-related policies in China, the EU, and the US will drive demand for these essential resources. The demand for electric vehicles (EV) and their components is also expected to increase due to policies in these countries. However, only countries with free trade agreements with the US are able to export critical minerals for EV batteries; additionally, US demand for battery components is projected to decrease significantly by 2029 due to tax credit requirements that mandate manufacturing and/or assembly in North America.

Figure 1: Main impacts and affected agents of EU, US, and China climate policies

Notes: CM stands for critical minerals, EV for electrical vehicles, RE for renewable energy, and FF for fossil fuels. Traditional sectors are those not linked to green transition and/or related to supply/ demand of fossil fuels. Emerging sectors are those related to green transition like EV manufacturing, critical minerals, or renewable power. Source: Aldaz-Carroll et al. 2024.

EUDR could discourage agricultural exports to the EU

Many of these policies are likely to disadvantage exporters in developing countries, as they may experience challenges related to declining demand, domestic content requirements, loss of competitiveness from the higher carbon intensity of their exports, or insufficient resources to satisfy new regulations. Developing countries that fail to meet these standards risk losing market access and being excluded from global supply chains, sacrificing the poverty-reducing benefits of trade.

For example, the EUDR covers seven agricultural commodities-- cattle, cocoa, coffee, palm oil, rubber, soy, and wood, and their derivatives. It requires evidence that agricultural commodities and their derivatives were not harvested from deforested land after 2020. Although this applies only to EU operators and traders, the associated compliance costs may be passed down the supply chain, burdening producers in developing countries with expensive due diligence, data gathering, and reporting requirements. This, in turn, could lead to reduced exports to the EU, particularly among smaller farmers who struggle to meet information requirements and adopt geolocation technology for traceability. Some producers may stop exporting to the EU altogether, opting instead to redirect their exports to markets with less stringent regulations despite lower profit margins, undermining the regulation’s original intent.

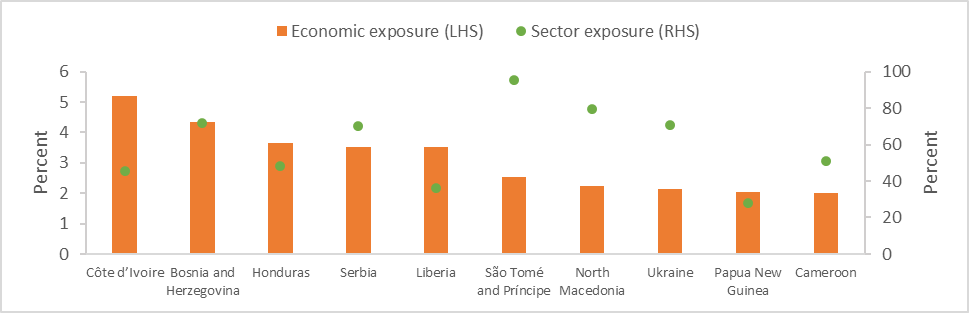

Figure 2: Top 10 developing countries according to their economic exposure to EUDR

Note: Sector and economic exposure are exports of EUDR affected products to the EU divided by exports of EUDR affected products to world and GDP, respectively. Source: Authors’ calculation based on 2022 data from the World Bank’s WITS.

Exporters of affected products that rely heavily on the EU market are most likely to be affected by EUDR. For example, 96% of Sao Tome and Principe’s global exports of affected products are sent to the EU, while affected exports to the EU account for 5.2% of Cote d'Ivoire 's GDP (Figure 2).

China, EU, and US climate policies also present considerable opportunities for developing countries

The opportunities generated by these policies are also considerable. As climate policies are implemented, they will boost demand for renewable energy, as well as the price of critical minerals needed to produce solar panels, wind turbines, batteries, and high-efficiency appliances. The global market for minerals critical to the green transition is estimated at US$246.4 billion annually, and projected to more than double within the next 15 years (IEA 2023). This presents a prime opportunity for countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo and Guinea, where critical minerals comprise a substantial share of exports.

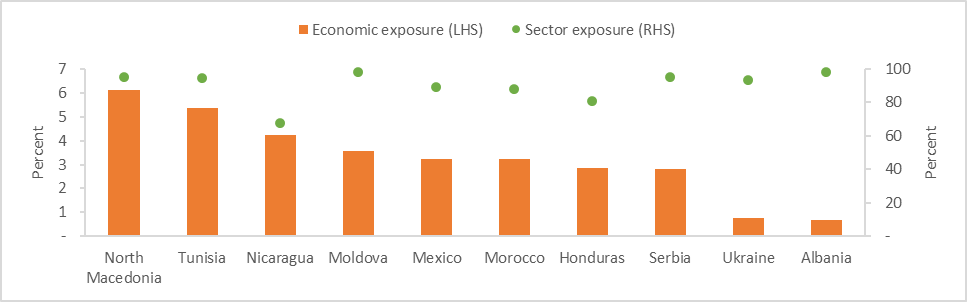

Environmental standards and policies in China, EU, and US are expected to increase demand for green technology and components. North Macedonia, Tunisia, and Moldova already export over 90% of their EV components to these three markets; in North Macedonia, these exports make up 6% of GDP (Figure 3). However, starting in 2029, only batteries fully produced or assembled in North America will benefit from the subsidies provided by the US IRA.

Figure 3: Top 10 developing countries according to economic exposure to impacts of the EU, US, and China policies on EV components exports

Note: Data includes components of EVs, excluding batteries. Sector and economic exposure are export of EV components to the three economies divided by exports of EV components to the world and GDP, respectively. Source: 2022 data from the World Bank’s WITS.

Taking developing countries into account when designing climate policy

Effective measures must be implemented to mitigate the adverse effects of these climate policies on developing countries, as well as help them overcome compliance challenges and seize the associated opportunities. Developing countries should aim to fulfil their Nationally Determined Contributions by advancing renewable energy initiatives and decarbonisation efforts. This may involve eliminating tariff and non-tariff biases that favour carbon-intensive goods over green goods and technology, attracting investment in export-oriented green sectors, and removing barriers to participation in green value chains. Establishing carbon pricing mechanisms that adhere to international standards, as well as strengthening infrastructure for carbon measurement, reporting, and verification, will help ensure compliance. The EU, US, and China can play a critical role here by designing policies that promote the green transition while minimising the negative impact on developing countries.

However, the continued use of protectionist measures in these three economies, such as local content requirements and discriminatory subsidies, may encourage other countries to follow, ultimately harming LMICs and delaying their green transition. Green subsidies and carbon pricing regulations should be structured to minimise unnecessary trade restrictions and prevent discriminatory practices. Considering the needs of developing countries in climate policy design can accelerate global GHG emissions reduction, while promoting poverty reduction and shared prosperity. This can involve sharing best environmental practices, adopting a phased approach accounting for the limited capacities of developing countries, and providing financial and technical assistance.

Lastly, international cooperation and coordination are essential to ensuring a swift transition to a low-carbon future that is fair and inclusive for all countries (WTO 2024). This includes harmonising compliance requirements and reaching agreements on green subsidies within the World Trade Organization’s framework, as well as addressing data gaps and developing infrastructure for carbon tracing, measurement, and verification.

References

Aldaz-Carroll, E, E Jung, M Maliszewska, and I Sikora (2024), "Global ripple effects: Knock-on effects of EU, US, and China climate policies on developing countries’ trade," World Bank.

Attinasi, M G, L Boeckelmann, and B Meunier (2023), “Unfriendly friends: Trade and relocation effects of the US Inflation Reduction Act,” VoxEU.

Gründler, K, P Heil, N Potrafke, and T Wochner (2023), “The global impact of the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act: Evidence from an international expert survey,” EconPol Policy Report.

Harstad, B (2023), “Trade or trees?” VoxDev.

International Energy Agency (IEA) (2023), "Critical minerals market review 2023," International Energy Agency.

Kleimann, D, N Poitiers, A Sapir, S Tagliapietra, N Véron, R Veugelers, and J Zettelmeyer (2023), “How Europe should answer the US Inflation Reduction Act,” Bruegel Policy Brief, Issue 04/23.

Shapiro, J S (2023), “The hidden pollution subsidy in global trade,” VoxDev.

WTO, OECD, United Nations, and World Bank (2024), "Working together for better climate action: Carbon pricing, policy spillovers, and global climate goals".

[1] US IRA incentives might be diminished or conditions changed by the new administration. As of January 2025, President Donald Trump has paused all IRA funding disbursement.