Despite the increased access to primary education in sub-Saharan Africa, secondary school enrolment and completion remains low. Evidence from Uganda reveals that universal secondary school policies can play a transformative role in women’s empowerment.

The widespread adoption of free primary education policies across sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) led to a surge in enrolment, with the adjusted net primary enrolment ratio reaching 20% (UNESCO 2015). However, this expansion revealed a significant gap: primary-to-secondary transition rates remained below 50%, while a growing share of youth remained out of school—36% at the lower secondary level and 57% at the upper secondary level. Secondary school completion rates also stagnated at around 30% (Lewin 2009, UNESCO 2019). To bridge this gap, governments across the region begun to extend these education reforms beyond primary schooling. By 2020, at least 17 countries had implemented some form of free or reduced-fee secondary schooling policy (Mastercard Foundation 2020).

However, despite its potential benefits, debate persists on whether the high costs of universal secondary education are justified by the individual and societal returns. While research highlights the positive impacts of free primary education, rigorous evidence on the long-term effects of secondary school expansion remains scarce.

Uganda was the first to take a bold step in this direction. In 2007, it introduced the Universal Post-Primary Education and Training (UPPET) program—widely known as the Universal Secondary Education (USE) policy, addressing two key barriers to education—school tuition fees and inadequate facilities (Snilstveit et al. 2016, UNICEF 2021). Designed to make secondary education accessible to all, especially girls and disadvantaged communities, the policy has now been in place for over 15 years. Our research (Kazibwe and Li 2025) shows that beyond improving educational attainment, the USE policy is cost-effective and has played a transformative role in advancing women’s empowerment—enhancing employment prospects, delaying marriage and childbirth, and strengthening women’s decision-making power within households.

Why secondary education matters for women’s empowerment

Secondary education is a critical inflection point in young people’s lives, shaping their transition to adulthood. This period is particularly important for girls, who often face heightened risks of early marriage, adolescent pregnancy, and gender-based violence. This also serves as a gateway to the workforce, equipping young people with essential skills for adaptability, resilience, and innovation in a dynamic job market. Removing financial barriers to secondary education can mitigate these risks, while equipping young women with skills essential for economic independence.

A growing body of research underscores the high returns of investing in girls’ education, as it expands labour market opportunities, strengthens women’s autonomy, and improves household bargaining power (Duflo 2012). Education is also linked to delayed marriage and childbirth, improved health behaviours, and shifts in gender norms (Baird and Özler 2016, Buvinic and O’Donnel 2019, Duflo et al. 2021). However, the impact of broad secondary education policies on women’s empowerment in SSA remains unclear. Uganda’s USE policy offers a unique case to examine how removing financial barriers to secondary education influences long-term empowerment.

Uganda’s universal secondary education policy

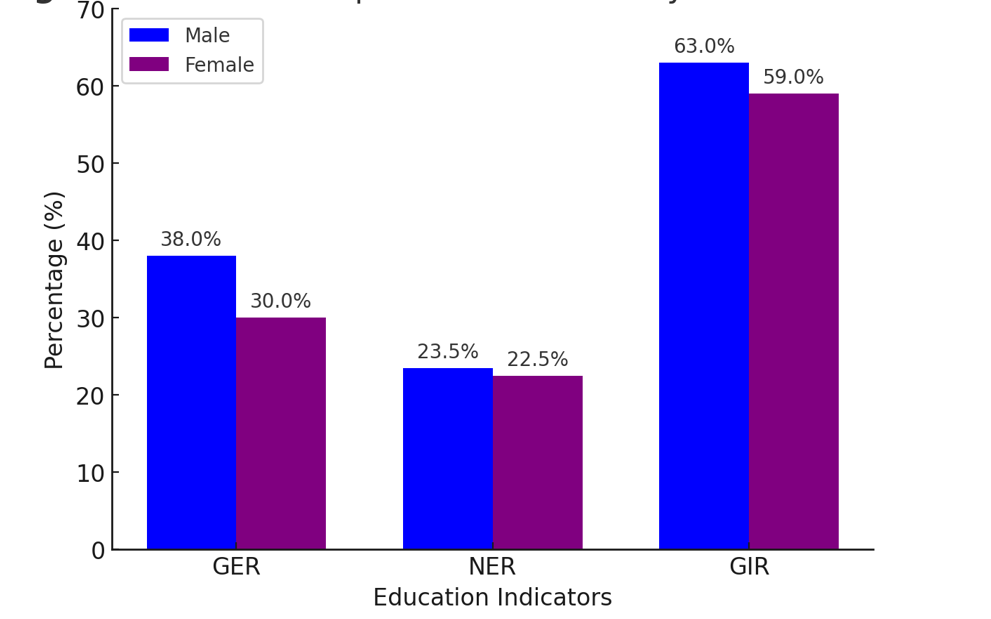

Before the USE policy, high tuition fees and inadequate infrastructure kept secondary school enrolment low in Uganda, particularly for girls (Figure 1) and students from low socioeconomic status. To address this, Uganda introduced the USE policy in 2007, eliminating tuition fees and expanding school capacity through capitation grants for government and participating private schools. The policy also covered exam fees and provided targeted bursaries for girls and disadvantaged children. The government committed to establishing at least one secondary school per administrative level 3 area or partnering with private institutions to reduce overcrowding, shorten travel distances, and improve education access. Households, however remained responsible for covering additional educational expenses, such as exercise books, meals, and other scholastic materials. By 2009, enrolment had surged by 25%, with girls constituting 45.7% of total students (Ministry of Education and Sports 2009).

Figure 1: Gender disparities in secondary education pre-USE

Source: Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) 2006

Estimating the long-term impacts of universal secondary education

Our study examines the long-term effects of the USE policy on women’s outcomes, exploring whether increased access to secondary education translated into broader empowerment gains. We focus on three key research questions:

- Did the USE policy improve women’s educational attainment?

- Did secondary education expansion lead to greater women’s empowerment?

- What are the pathways through which the policy influenced empowerment outcomes?

To assess empowerment, we analyse three interconnected dimensions:

- Human and social assets: access to enabling resources.

- Decision-making power: reflecting agency within households.

- Gender norms and beliefs: capturing attitudes toward women’s roles and intimate partner violence.

Using a difference-in-differences approach, we compare cohorts of women who were eligible for USE to those who were not, leveraging variations across districts with different levels of pre-policy secondary school access. This allows us to isolate the policy’s effects and understand its broader implications for gender equality and social mobility.

Universal secondary education enhanced schooling, employment, and autonomy

Our findings reveal several important trends:

- Increased schooling: The policy added nearly one year of schooling for women, with secondary and tertiary completion rates rising by 6-7 percentage points.

- Greater access to resources: Women exposed to USE experienced delayed life events, leading to higher agency and well-being. An additional year of schooling increased access to empowerment resources by 14 percentage points.

- Shifting social norms and greater decision-making: USE-exposed women demonstrated greater autonomy and progressive gender attitudes. They were 11 percentage points more likely to challenge restrictive gender norms, reject justifications for intimate partner violence, and 20 percentage points more likely to participate in household decision-making (e.g. household purchases healthcare choices).

These empowerment gains were likely driven by:

- Greater labour market participation: More educated women were more likely to enter skilled employment and shift away from agriculture and domestic work. Increased labour force participation strengthens women’s financial independence and household bargaining power, as they contribute more to family income.

- Delayed marriage and childbirth: Women with USE exposure were more likely to have narrower spousal education gaps, marry later and have fewer children, consistent with research linking education to higher opportunity costs of early childbirth (Brudevold-Newman 2021, Chaijaroen and Panda 2023). These delays suggest improved control over life choices, a key aspect of empowerment.

- Access to information: Greater exposure to media and digital connectivity enhanced women’s awareness of opportunities, rights, and health services, further reinforcing empowerment gains.

Universal secondary education policies are cost-effective and scalable

Uganda’s USE policy demonstrates that free secondary education is a powerful tool for women’s empowerment, influencing not only education but also employment, marriage, fertility, and gender norms. The policy offers key lessons for African policymakers:

- Cost-effectiveness: At an estimated cost of USD$76 per student annually, Uganda’s USE policy is more affordable than similar programmes in Kenya (Brudevold-Newman 2021) and Ghana (Duflo et al. 2021).

- Scaling secondary education: While free primary education is widespread, secondary schooling remains limited. Expanding such programmes can boost gender equality and economic participation.

- Beyond education: Schooling alone cannot dismantle entrenched gender norms. Complementary policies addressing cultural barriers, workplace discrimination, and reproductive health are crucial.

Implications for universal secondary education policies

Eliminating financial barriers to education does more than increase school attendance—it transforms lives. Uganda’s USE policy shows that free secondary education enhances economic opportunities, delays marriage, and reshapes gender norms, driving long-term empowerment.

As sub-Saharan Africa advances towards achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals, the case for universal secondary education is stronger than ever. Investing in girls’ education is not just a moral imperative, it is essential for economic and social progress.

References

Baird, S, and B Özler (2016), “Sustained effects on economic empowerment of interventions for adolescent girls: Existing evidence and knowledge gaps,” Center for Global Development.

Brudevold-Newman, A (2021), “Expanding access to secondary education: Evidence from a fee reduction and capacity expansion policy in Kenya,” Economics of Education Review, 83: 102127.

Buvinic, M, and M O’Donnel (2019), “Gender matters in economic empowerment interventions: A research review,” World Bank Research Observer, 34(2): 309–346.

Chaijaroen, P, and P Panda (2023), “Women’s education, marriage, and fertility outcomes: Evidence from Thailand’s compulsory schooling law,” Economics of Education Review, 96: 102440.

Duflo, E (2012), “Women empowerment and economic development,” Journal of Economic Literature, 50(4): 1051–1079.

Duflo, E, P Dupas, and M Kremer (2021), “The impact of free secondary education: Experimental evidence from Ghana,” NBER Working Paper.

Kazibwe, D, and J Li (2025), “Universal secondary education, schooling and women’s empowerment: Evidence from Uganda,” Journal of Development Economics, 174: 103464.

Lewin, K M (2009), “Access to education in Sub‐Saharan Africa: Patterns, problems and possibilities,” Comparative Education, 45(2).

Mastercard Foundation (2020), "Secondary education in Africa."

Ministry of Education and Sports (2009), "Uganda educational statistics abstract."

Snilstveit, B, J Stevenson, R Menon, D Phillips, E Gallagher, M Geleen, et al. (2016), “The impact of education programmes on learning and school participation in low- and middle-income countries,” International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie).

Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) (2006), "National population and housing census: Analytical report."

UNESCO (2015), "Regional overview: Sub-Saharan Africa. Education for All 2000–2015: Achievements and challenges," EFA Global Monitoring Report.

UNESCO (2019), "Global education monitoring report 2019: Migration, displacement and education – Building bridges, not walls."

UNICEF (2021), "Transforming education in Africa."