Can taking textbooks home improve student learning when resources are highly constrained? New research from fragile areas in the Democratic Republic of the Congo suggests it can.

For decades, governments and international donors have poured resources into education, believing that increased access to schools and learning materials would organically translate into better educational outcomes; however, this assumption has often been proven overly optimistic. Despite rising enrolment rates, learning levels remain low in many developing countries, a challenge often referred to as the global learning crisis (Glewwe and Muralidharan 2016).

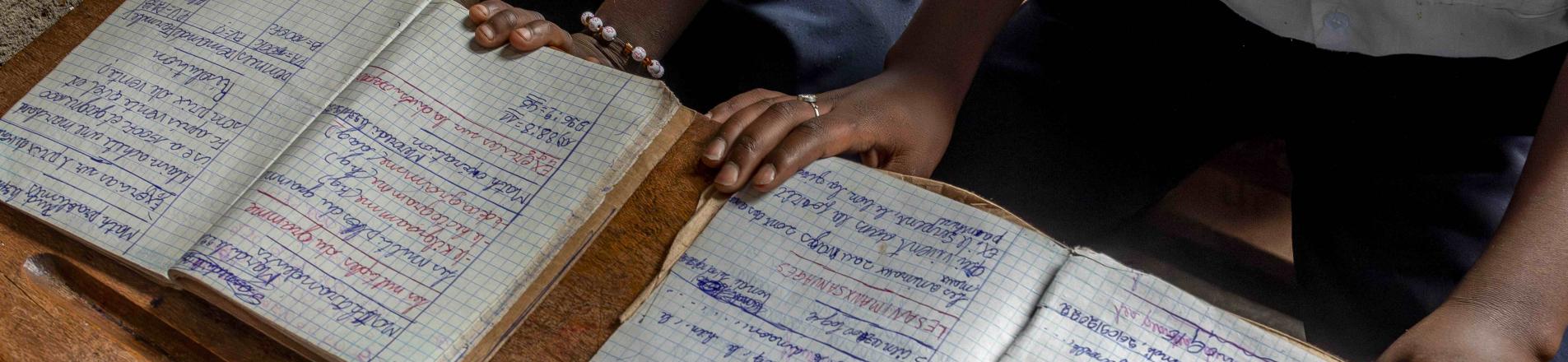

Several factors contribute to the gap between schooling and actual learning, including teacher shortages, outdated curricula, and poorly maintained school facilities all play a role (World Bank 2018). Educational resources are also frequently underutilised, especially textbooks. In many contexts, books are not fully utilised by teachers, often sitting in storage rooms instead of in the hands of students (Sabarwal et al. 2014). Simply providing students with textbooks does not necessarily improve learning unless they are actively used.

In Falisse et al. (2024), we investigate whether a simple behavioural intervention—encouraging students to take textbooks home for self-study—can improve learning outcomes. Our research, conducted in 90 primary schools in the province of South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), explores whether textbooks become more effective learning tools when students are incentivised to engage with them outside school hours. At the time of the study, South Kivu was in a fragile state due to local conflict; since then, the situation has escalated into all-out war, undermining any attempts to improve educational outcomes. The current situation makes the need for effective resource utilisation all more urgent.

The experiment: Encouraging students to take books home

The Textbooks for Self-Study (TSS) intervention was designed to encourage students in grades five and six to take home French (the language of instruction from level Primary 4) and math textbooks regularly. The programme introduced the following key incentives:

- Public recognition: Students who consistently returned their books undamaged and completed weekly quizzes received stars displayed in their classroom.

- Classroom rewards: If at least 75% of students in a class followed the routine, the class received a few more extra school supplies (e.g. pens and paper).

- School incentives: Schools received a small financial compensation to offset concerns about potential loss or damage of books.

The intervention was implemented in half of the selected schools, while the other half served as a control group. The impact was measured using standardised tests in French and math, as well as data on participation in the national primary school exam.

Taking textbooks home: Small behavioural change, large educational gain

Our results indicate that simply allowing students to take textbooks home, coupled with modest low-cost incentives, significantly improved student engagement and learning outcomes. Students in the treatment schools were 14% more likely to take the national exam, and those who passed obtained higher scores than their peers in control schools. In addition, students in the intervention group showed better performance on a French language test, with score gains of 0.25–0.27 standard deviations. These findings suggest that access to textbooks outside the classroom, combined with behavioural incentives, can positively impact learning.

However, the study found no statistically significant effect on math performance. This aligns with prior research suggesting that literacy skills may be more easily improved through self-study, whereas math learning often requires greater teacher involvement (De Jong 2015).

Understanding the mechanisms behind taking books home

There are three key reasons why the intervention was effective:

- Students in treatment schools were more likely to do homework regularly and seek help from family members, particularly siblings. This suggests that textbooks provided a stimulus or support for learning outside of school.

- Teachers in treatment schools used textbooks more often in class. While the programme did not directly target teaching methods, greater student familiarity with textbooks made it easier for teachers to integrate textbooks into their lessons.

- The intervention increased student motivation. Students in treatment schools reported greater enthusiasm for learning, were more likely to say they found textbooks useful, and expressed a stronger desire to continue to secondary education.

Interestingly, the study found no significant changes in parental engagement. While students sought help from peers and siblings, parents' involvement in their children's education remained largely unchanged.

Taking home books benefitted at-risk students the most

The intervention appeared to have the largest effects on students who were initially lower-performing and those in classrooms with weaker teachers. This suggests that self-study initiatives can be particularly valuable in resource-constrained schools where teacher quality is low. Additionally, students saw larger learning gains in schools that, prior to the intervention, prevented students from taking textbooks home (often due to fears that books would be lost or damaged). This highlights how restrictive school policies on textbook use can inadvertently limit students' learning opportunities.

Policy implications for low-cost education solutions in fragile states

One major challenge in global education is finding cost-effective interventions that work in settings where resources are heavily constrained–and risk being further constrained in the coming years given international aid cuts. Many large-scale education reforms, such as hiring additional teachers or implementing new digital learning programmes, are expensive and difficult to sustain.

The TSS approach offers a promising alternative by activating idle resources. The biggest cost of this intervention were the monitoring expenses, which can be lowered significantly if scaled up. By leveraging existing resources more efficiently, rather than introducing costly new materials, this approach aligns with recent research emphasising the importance of optimising educational inputs (Glewwe and Muralidharan 2016).

Additionally, as developing countries consider strategies to improve education in conflict-affected areas, understanding how self-study initiatives interact with broader school policies and teacher training programs will be crucial.

The future of global education interventions

This study finds that encouraging students to use existing learning materials more effectively can significantly enhance educational outcomes, particularly in fragile states. By focusing on student behaviour and motivation, rather than costly infrastructure or technology, the TSS approach offers a scalable, low-cost solution to improving learning in resource-constrained environments. Such interventions can play a crucial role in broader efforts to close the global learning gap and expand access to quality education. Now more than ever, with global aid spending under threat, rising political tensions, and widening inequalities, we need to scale effective low-cost high-impact interventions to promote opportunity for all.

References

De Jong, J H A L (2015), “Why learning English differs from learning math and science,” Pearson Blog.

Falisse, J B, M Huysentruyt, and A Olofsgård (2024), “Incentivising textbooks for self-study: Experimental evidence from the Democratic Republic of the Congo,” The Economic Journal, 134(664): 3262–3290.

Glewwe, P, and K Muralidharan (2016), “Improving education outcomes in developing countries: Evidence, knowledge gaps, and policy implications,” in Handbook of the Economics of Education, Vol. 5, Elsevier, 653–743.

Kremer, M, C Brannen, and R Glennerster (2013), “The challenge of education and learning in the developing world,” Science, 340(6130): 297–300.

Sabarwal, S, D K Evans, and A Marshak (2014), “The permanent input hypothesis: The case of textbooks and (no) student learning in Sierra Leone,” Unpublished manuscript.

World Bank (2018), "World Development Report 2018: Learning to realize education’s promise."