In 2004, a randomised controlled trial provided individuals in Malawi with information about their HIV status, despite treatment being unavailable in the country at the time. Did knowing one’s diagnosis help or hurt?

An important and ongoing debate in public health policy concerns the consequences of providing health information when treatment options are limited or unavailable. This issue has gained renewed importance with recent decisions by the US government to cut funding for various development programmes, including USAID, that support individuals with life-threatening diseases. These cuts could have severe consequences for individuals diagnosed with conditions such as HIV if they lose access to essential treatment. Beyond the immediate health effects, the cuts could also fuel fatalistic behaviours, further compounding negative impacts.

We explored the consequences of receiving information about HIV status during a time when treatment options were unavailable in Malawi, where incentives to learn HIV test results were randomly assigned (Ciancio et al. 2025).

The promise and peril of health screening

Screening for diseases is a widely promoted health practice, empowering individuals to adopt preventive behaviours or seek earlier treatment (Dupas 2011). Yet, in many low‐income settings, the rapid expansion of diagnostic capacity has outpaced the availability of effective treatment (McNerney 2015). In such contexts, receiving a diagnosis may generate despair, trigger risky health behaviours, or induce fatalistic attitudes that undermine survival. Our study focuses on this critical gap between diagnosis and treatment availability by examining the long‐term effects of HIV testing in rural Malawi in 2004, a setting and time where antiretroviral treatment (ART) was unavailable and only gradually expanded years later (Baranov and Kohler 2018).

Studying behaviour in response to learning HIV status in Malawi

This study followed a cohort of nearly 3,000 individuals from the Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Health (MLSFH) between 2004 and 2019 (Kohler et al. 2020). In 2004, respondents were offered an HIV test for the first time during a large-scale survey, receiving randomised financial incentives and facing different (randomised) distances to the nearest HIV results centre (Thornton 2012). This variation created exogenous differences in the likelihood of learning one’s HIV status that we used to study causal effects.

By comparing outcomes among individuals who learned their HIV status with those who did not, we can isolate the causal impact of health information. In rural Malawi, where ART became slowly accessible starting in 2007, informing individuals about their HIV-positive test in 2004 implied that they were informed of a diagnosis for a deadly disease for which there was no treatment or cure at the time. Previous research shows that HIV-positive individuals who learned their results were more likely to take precautions to protect others than HIV-positive individuals who did not learn their results (Thornton 2008).

Information on HIV status, in the absence of treatment, had severe consequences

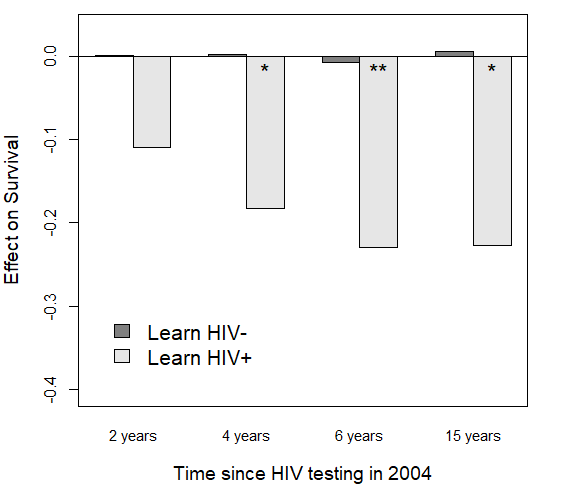

Figure 1: Impact of learning HIV status on survival

Note: ** (*) indicate statistical significance at 95% (90%) confidence.

Our analysis shows that receiving an HIV-positive diagnosis in the absence of treatment had severe long-term consequences (Figure 1). Two years after testing, HIV-positive individuals who learned their status exhibited an 11-percentage point lower survival rate compared to those who were also HIV-positive but did not know their status. Six years after testing, this gap widened to around a 23-percentage point difference; by then, survival among HIV-positive individuals who did not learn their status was approximately 85%, and only about 62% for those who did learn their positive status in 2004. Even 15 years after the initial testing, the mortality gap persisted, underscoring that the negative effects of receiving bad news were long-lasting and persistent.

In contrast, learning of an HIV-negative status had no discernible effect on survival. This divergence suggests that the health information itself is not inherently harmful; instead, it is the context in which the information is delivered and the absence of treatment options that transforms a diagnosis into a death sentence.

Why does receiving bad news hurt chances of survival?

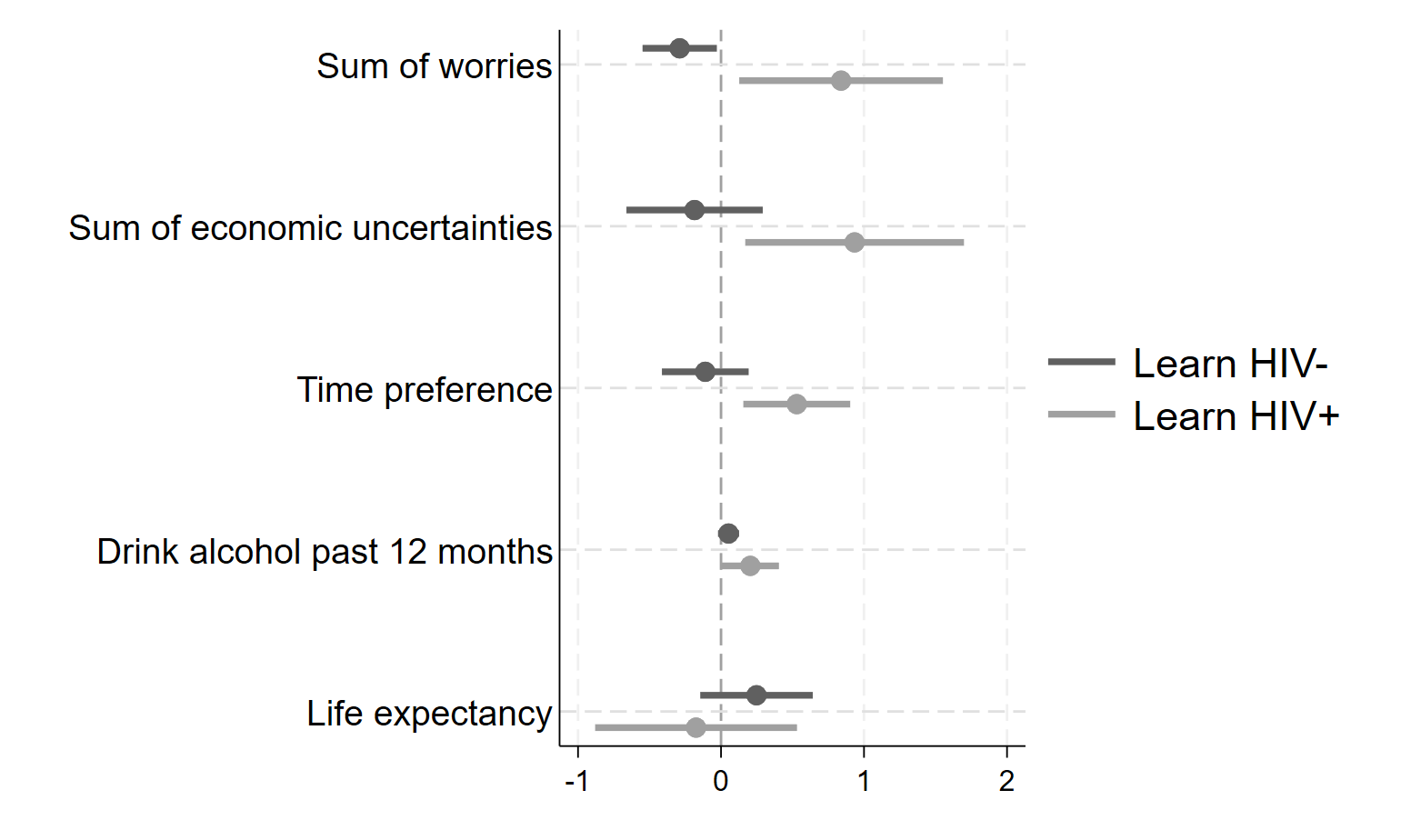

Figure 2: The effects of learning HIV status on various mechanisms

Note: Data from a survey collected in 2005, approximately two months after test results were available. Dots are point estimates and horizontal lines are 95% confidence intervals.

To understand why receiving an HIV-positive diagnosis led to a reduced probability of survival, we examine several potential mechanisms using data from a survey conducted approximately two months after the test results were made available (Figure 2). The evidence points toward a series of behavioural and psychological responses that likely contributed to worse health outcomes:

- Heightened anxiety and worry: Individuals who learned their HIV-positive status reported significantly more worries about their health and AIDS specifically. This increased anxiety may have contributed to stress-related physiological responses that undermine health over time.

- Economic uncertainty and altered time preferences: The follow-up survey found that those who received an HIV-positive diagnosis exhibited higher economic uncertainty. They also shifted their time preferences dramatically towards the present and away from the future. The HIV-positive diagnosis has altered how individuals value the future, potentially reducing investments in health-promoting behaviours.

- Riskier health behaviours: We also find an increase in risky behaviours among individuals who learned they were HIV positive. For example, we find a marked rise in alcohol consumption, a behaviour often linked to coping with distress. Such risky behaviours can further compromise health, especially in resource-poor environments.

Taken together, these behavioural responses create a feedback loop. The shock of receiving bad news, in the absence of actionable treatment, fosters an environment of fatalism and despair. Instead of mobilising protective behaviours, the diagnosis leads to practices that further jeopardise survival.

Policy implications in an ideal world: Matching HIV screening with support

While we find that health information without treatment can have harmful effects, it should not be interpreted as a case for withholding information. Screening can yield critical benefits we do not capture, such as reduced risky sexual behaviour and efforts to protect future partners, which are essential for slowing disease transmission. The potential for health information to promote prevention remains substantial, even when treatment options are limited.

That said, our findings highlight important considerations for public health policy, especially in low-resource settings and for conditions without effective treatment, including in high-income countries (e.g. Huntington’s or Parkinson’s disease). Expanding diagnostic capacity must go hand in hand with investments in treatment and supportive care to avoid unintended harm.

Screening programmes should include integrated counselling to help individuals process information and reduce the risk of fatalistic responses. Treatment infrastructure must be developed alongside testing to ensure that a diagnosis is followed by meaningful action. Public health strategies should also reflect local realities; in high-prevalence, low-treatment areas, alternative approaches, such as community-based support or phased rollouts, may reduce harm. Finally, since health shocks can deepen economic insecurity, combining screening with economic support, such as cash transfers or access to credit, can help individuals better cope with a diagnosis and its consequences.

Lessons for global health in a post-aid world

The lessons from our study extend well beyond HIV in Malawi. As low- and middle-income countries face a growing burden of noncommunicable diseases, a familiar challenge is re-emerging: diagnostic capabilities are advancing faster than access to treatment. For conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, or cancer, the psychological and behavioural consequences of learning one’s risk, without options for care, may mirror the patterns we observe among HIV-positive individuals in our research.

This mismatch between screening and treatment capacity poses an urgent question: how can health information be empowering rather than paralysing? The answer lies in integrated systems that treat diagnosis and treatment as part of a continuum, not as isolated steps. This issue has become even more pressing in light of recent aid cuts to global health programmes, including USAID initiatives that fund treatment for HIV and other critical conditions. Our findings underscore this danger: without sustained international support, expanding access to health information without follow-up care risks deepening both the physical and psychological burden of disease.

References

Baranov, V, and H-P Kohler (2018), “The impact of AIDS treatment on savings and human capital investment in Malawi,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 10(1): 266–306.

Ciancio, A, F Kämpfen, H-P Kohler, et al. (2025), “Surviving bad news: Health information without treatment options,” American Economic Review: Insights, 7(1): 1–18.

Dupas, P (2011), “Health behavior in developing countries,” Annual Review of Economics, 3(1): 425–449.

Kohler, I V, C Bandawe, A Ciancio, F Kämpfen, C F Payne, J Mwera, J Mkandawire, and H-P Kohler (2020), “Cohort profile: The mature adults cohort of the Malawi Longitudinal Study of Families and Health (MLSFH-MAC),” BMJ Open, 10(10).

McNerney, R (2015), “Diagnostics for developing countries,” Diagnostics, 5(2): 200–209.

Thornton, R L (2008), “The demand for, and impact of, learning HIV status,” American Economic Review, 98(5): 1829–1863.

Thornton, R L (2012), “HIV testing, subjective beliefs and economic behavior,” Journal of Development Economics, 99(2): 300–313.