The construction of rural roads improved women's empowerment by reducing mobility restrictions, fostering progressive norms, increasing girls' educational enrolment and enhancing female agency. However, challenges remain in finding ways to enhance women's financial autonomy and increase their labour force participation.

Women worldwide have historically faced poor socio-economic outcomes, with India—home to approximately 17% of the global female population—serving as a compelling case study. According to the Periodic Labour Force Survey (2019–20), female labour force participation in India is alarmingly low at just 30%, ranking among the lowest globally and showing a steady decline over recent decades. Furthermore, data from the India Human Development Survey (2011–12) reveal that over 30% of women report mobility restrictions, and more than 40% experience domestic violence. Physical mobility constraints are widely recognised as a significant barrier to women's socio-economic engagement (Field and Vyborny 2022, Bankar et al. 2018, Goel 2023). Societies where women face challenges in traveling freely often exhibit stricter gender norms and lower female labour force participation. In our recent study (Nandwani and Roychowdhury 2024), we explore the effects of a transportation infrastructure policy in India that invested in rural road development, focusing on its impact on women’s autonomy and empowerment.

How can better roads empower women?

The Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana (PMGSY), launched in 2000, is the Government of India's flagship programme aimed at connecting unconnected villages with populations exceeding 500 to the nearest market centres through all-weather roads. The programme was implemented in phases, prioritising villages based on population size, beginning with those having more than 1,000 residents, followed by those with populations over 500. Graphs 1 and 2 illustrate the spatial distribution of PMGSY roads between 2004 and 2010.

Paved rural roads offer significant potential benefits for women. Improved transportation and reduced travel costs facilitate easier movement within and beyond villages. In many developing countries, women must travel long distances for basic tasks such as fetching water and firewood. With faster travel times, women can allocate more time to productive activities. Additionally, better connectivity to market towns expands access to educational and employment opportunities outside agriculture. Rural women, often disadvantaged by poor infrastructure, limited economic and educational prospects, and restrictive gender norms, can gain from increased exposure to people from outside their villages and market towns, potentially challenging traditional gender roles.

However, the extent of these benefits may be constrained by entrenched social norms. Societal attitudes toward female mobility could limit the effectiveness of infrastructure investments in advancing women’s autonomy. As a result, the impact of rural road construction on women’s empowerment has been uncertain.

Measuring women’s empowerment and road access in India

We utilise several socio-economic indicators to assess women’s empowerment comprehensively. Influential studies define women’s empowerment as the process through which historically marginalised individuals gain the ability to make choices, voice opinions, and influence both their personal lives and broader community decisions (Kabeer 1999). Empowerment, therefore, is a multidimensional concept (Moghadam 1996, Kabeer 1999, Janssens 2010) encompassing not only economic factors like work, income, education and assets but also social and political dimensions (Kabeer et al. 2011, Golla et al. 2011).

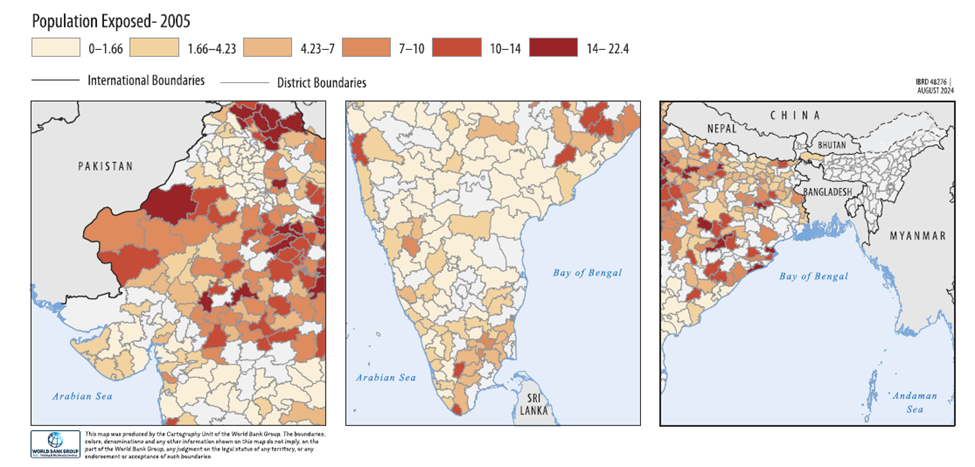

Figure 1: Rural population exposed to PMGSY road up to 2004

Source: Author’s own calculations using administrative data on PMGSY roads construction.

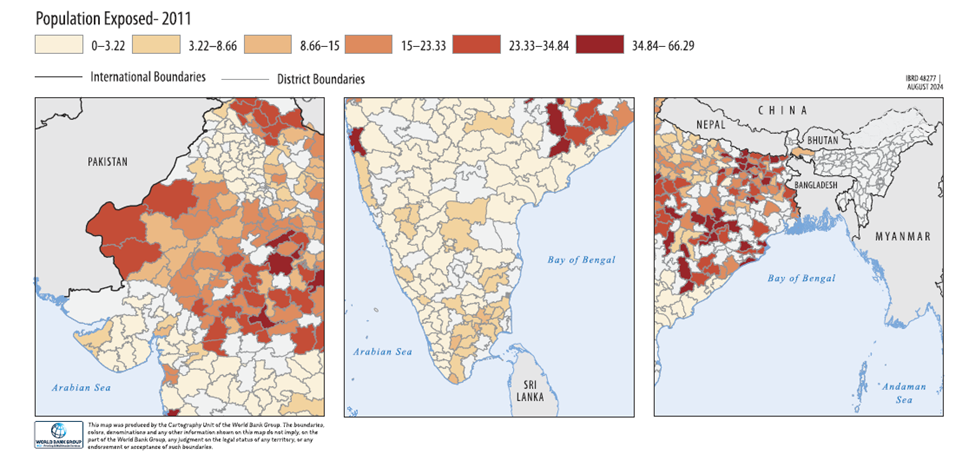

Figure 2: Rural population exposed to PMGSY road up to 2010

We categorise the variables used to measure women's empowerment into five primary groups: (a) restrictions on female mobility, (b) norms related to domestic violence, (c) intra-household agency, (d) financial autonomy, and (e) other gender-related outcomes (e.g. practices like purdah[PD1] [I2] which is the practice of secluding women from public observation through face covering).

To analyse these outcomes, we use two large datasets: IHDS and the National Sample Survey (NSS). IHDS is a nationally representative, multi-topic panel survey conducted by the National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER). The first wave of IHDS was conducted in 2004-05, followed by another in 2011-12, surveying approximately 40,000 households per wave. IHDS includes a dedicated module on women, administered to one randomly selected married female over 15 years old in each household, covering topics such as female mobility, domestic violence, reproductive health, and education. NSS, conducted by the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, provides detailed information on employment and education, though it does not track the same households across survey rounds as IHDS does.

We also use administrative data on rural roads constructed under the PMGSY program, publicly available through the Online Management Monitoring System (OMMS). This data provides village-level information, which we aggregate at the district level to calculate the percentage of the population exposed to paved roads. We then merge this district-level road exposure data with the IHDS and NSS datasets.

Rural roads in India improve several dimensions of women’s empowerment

We use the variation created by the programme rule in exposure of population to new rural roads to identify the impact of PMGSY on women empowerment from 2000 to 2011. Since exposure of population to rural roads is a function of the distribution of sizes of unconnected villages in a district, it is likely to be exogenous to women's outcomes. Thus, leveraging the panel structure of the IHDS data, we employ two-way fixed effects (women fixed effects along with year fixed effects) to capture changes in individual exposure to paved roads over time.

Our findings indicate that the construction of rural roads has led to improvements in several dimensions of women’s empowerment. Greater exposure to paved roads reduces the mobility restrictions that women face, as fewer women report needing permission to leave their homes. The construction of roads also leads to more progressive norms surrounding domestic violence, with fewer women believing that domestic violence is common in their communities. Additionally, we observe greater female agency and a reduction in patriarchal norms in areas with more paved roads. However, the programme does not seem to impact women’s financial autonomy, as evidenced by no increase in bank account ownership or property rights.

In terms of education, we find that road exposure raises the likelihood of girls being enrolled in educational institutions. Despite this, we do not observe a corresponding rise in female employment. Interestingly, the programme does lead to higher male employment but does not significantly affect female employment rates.

Our results are robust to various potential confounding factors, including the initial provision of public goods and the presence of other welfare programmes that may particularly benefit rural women.

Road exposure does not raise female labour force participation rates

These findings suggest that while rural road infrastructure projects can significantly enhance gender norms and human capital investment among women, they do not directly improve female labour force participation rates. One possible explanation is that increased male employment and income, stemming from improved road access, may reduce the need for female employment, as noted in the literature (Mehrotra and Parida 2017, Mehrotra and Sinha 2017). The absence of improvements in female financial autonomy aligns with this observation.

Although our analysis effectively demonstrates the positive impact of road infrastructure on women's empowerment, limitations in data prevent a detailed exploration of the mechanisms driving improvements in gender norms without corresponding employment benefits. Nonetheless, this finding aligns with existing research highlighting the persistent challenges in improving female labour force participation rates in India (Afridi et al. 2018) and suggests that improvements in norms alone are insufficient without concurrent changes in the nature of available jobs (Deshpande and Singh 2021).

Policy insights on women’s mobility and empowerment from a large-scale government initiative

Infrastructure inadequacies that restrict mobility have been shown to significantly hinder economic activities, with women—historically constrained in employment and decision-making—facing disproportionate disadvantages due to spatial isolation. Our findings indicate that improving women’s mobility through rural road infrastructure development can lead to substantial benefits. These include reduced mobility restrictions, improved norms surrounding domestic violence, enhanced decision-making power within households, and greater likelihood of women attending educational institutions. By evaluating a large-scale government initiative in a non-experimental setting, this study offers critical policy insights for other developing countries, moving beyond the scope of small-scale micro-interventions. The findings are particularly pertinent to achieving Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5, which aspires to gender equality by 2030, highlighting the transformative role of infrastructure development in reducing gender disparities.

References

Afridi F, T Dinkelman, and K Mahajan (2018), "Why are fewer married women joining the workforce in rural India? A decomposition analysis over two decades," Journal of Population Economics 31: 783–818.

Bankar S, M Collumbien, M Das, R K Verma, B Cislaghi, and L Heise (2018), "Contesting restrictive mobility norms among female mentors implementing a sport-based programme for young girls in a Mumbai slum," BMC Public Health 18: 471.

Deshpande A, and J Singh (2021), "Dropping out, being pushed out or can’t get in? Decoding declining labour force participation of Indian women," IZA Discussion Paper No. 14639. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3905074 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3905074.

Field E, and K Vyborny (2022), "Women’s mobility and labor supply: Experimental evidence from Pakistan," Asian Development Bank Economics Working Paper Series 655.

Goel R (2023), "Gender gap in mobility outside home in urban India," Travel Behaviour and Society 32: 100559.

Golla A M, A Malhotra, P Nanda, and R Mehra (2011), "Understanding and measuring women’s economic empowerment," International Center on Research for Women (ICRW) report.

Janssens W (2010), "Women’s empowerment and the creation of social capital in Indian villages," World Development 38(7): 974–88.

Kabeer N (1999), "Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment," Development and Change 30(3): 435–64.

Kabeer N, S Mahmud, and S Tasneem (2011), "Does paid work provide a pathway to women’s empowerment? Empirical findings from Bangladesh," Working Paper.

Moghadam V M (1996), Patriarchy and Development: Women’s Positions at the End of the Twentieth Century, Oxford University Press.

Nandwani B, and P Roychowdhury (2024), "Rural road infrastructure and women’s empowerment in India," The World Bank Economic Review, lhae048.