New research uses mobile phone transaction data to shed light on the nature of religious adherence in Afghanistan, revealing that religiously motivated insurgent violence reduces religiosity while climate-induced income shocks increase religiosity.

Religion is a powerful force that shapes economic growth, cultural norms, political institutions, and social behaviour throughout the world (Weber 1905, Berman 2000, McCleary and Barro 2006, Campante and Yanagizawa-Drott 2015, Bryan et al. 2021, Becker et al. 2021). In fragile states, the combination of extreme instability and persistent vulnerability raise a number of important questions on how our environment shapes religious practice. Yet, empirical research on religiosity in such settings is constrained by the limits of traditional data. Surveys are often infeasible or unsafe during conflict, and when available, may be affected by reporting error (Hadaway et al. 1998, Brenner 2011, Brenner and DeLamater 2016). This highlights the potential for passively collected behavioural measures of religiosity, particularly those that can be scaled and sustained in fragile contexts.

To help fill this gap, we introduce a novel method to measure religiosity using mobile phone transaction data in Afghanistan (Dube et al. 2025). Afghanistan offers a relevant setting: it is one of the world’s most religiously observant countries (Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures 2022), where religion permeates everyday life, governance structures, and historical narratives (Barfield 2022). At the same time, it is shaped by decades of conflict, deep economic uncertainty, and the influence of armed groups, especially the Taliban, whose political ideology draws on a particularly extreme interpretation of Islam. In this setting, we develop a new behavioural measure of religious observance. To further illustrate how such a measure could be used to answer more pointed questions, we apply our new measure to study how religious engagement responds to violent conflict and climate shocks.

How can religious adherence be measured with phone data?

Prayer is a central pillar of Islam in Afghanistan, practiced five times a day within specified time windows that begin with the call to prayer. A defining feature of prayer in Afghanistan is silence and focus. Many Islamic religious texts and rulings have established that talking during prayer time invalidates prayer (Siddiqui 2005). Therefore, we propose that decreases in phone activity during prayer windows can provide an indication of the population's religious adherence. Drawing on an eight-year dataset (2013–2020) from one of the country's largest mobile networks, we analysed the anonymised logs of 6.5 to 8 million unique phone numbers annually. Because this network serves 292 of Afghanistan's 398 districts and reaches a substantial proportion of the nation's 39 million people, it provides an excellent opportunity to observe religious adherence at scale.

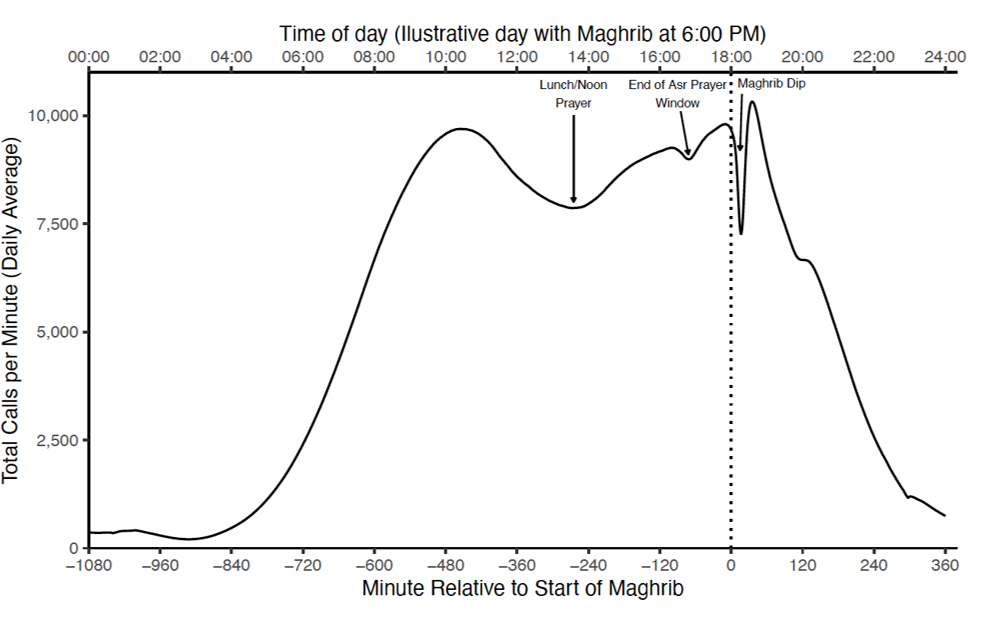

Within this context, we focus on mobile phone activity during the Maghrib prayer window, which takes places during a relatively short timeframe after sunset, occurring while most people are still awake, unlike the dawn and late-night prayer windows, which overlap with periods of sleep. Because phone use is restricted during prayer, we observe a pronounced drop in call volume when the sun sets and worship begins, which we refer to as the ‘Maghrib dip’. Figure 1 plots nationwide call volume minute-by-minute over a 24-hour window, averaged across all days from 2013 to 2020. Call volume drops sharply immediately after the prayer window opens (solid vertical line), capturing a consistent behavioural response to daily religious obligation.

Figure 1: Call volume throughout an illustrative day

We formalise the “Maghrib dip” measure of religious adherence by comparing outgoing call volume in the half hour before Maghrib with the half hour after, then expressing the decline as a percentage of average activity in these periods. On average, the dip reaches its lowest point around 17 minutes after Maghrib begins, with call volume decreasing by about 25% and returning to normal levels within thirty minutes.

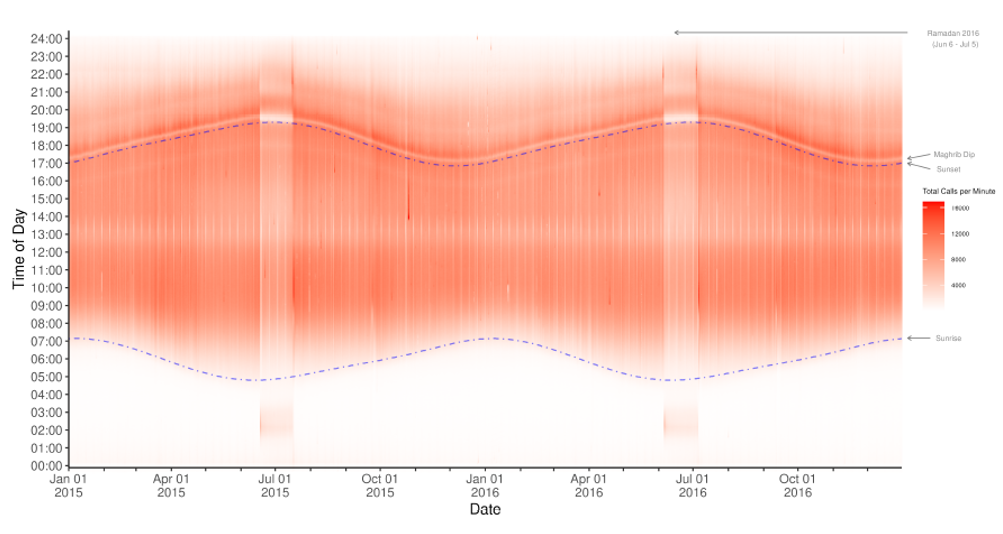

Figure 2: Intensity of mobile phone calls over time

Three pieces of evidence support the idea that the Maghrib dip is a valid and useful measure of religious adherence. First, the dip tracks daily and geographic variation in sunset times—visible in the undulating wave at the top of Figure 2 (which plots the total call volume for every minute of every day from January 2015 to December 2016)—rather than following a fixed schedule. This helps distinguish the decline in activity caused by Maghrib from routine daily activity like the end of workday or commuting. The figure also highlights two lighter vertical bands around June and July, corresponding to the holy months of Ramadan in those years. During these periods, we observe lower overall call volume and larger Maghrib dips, consistent with heightened religious observance.

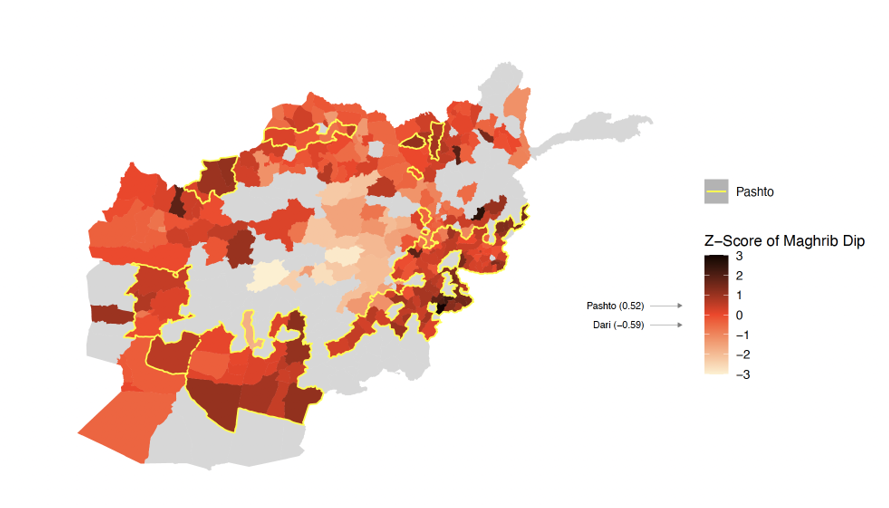

Second, we validate that individuals who self-report higher religiosity in surveys exhibit larger drops in phone usage, with a one standard deviation increase in self-reported religiosity corresponding to a 27% deeper dip. Third, areas known for stronger religious norms, such as Pashtun-majority districts, display more substantial declines, as demarcated by the yellow boundary in Figure 3, below. This further validates the connection between our metric and genuine religious observance.

Figure 3: Religious adherence by district

Another useful feature of mobile data is that reductions in different types of mobile transactions may reflect different motivations for religious observance. Religiosity is driven by some combination of inward-facing personal conviction (Allport and Ross 1967) and outward-facing social considerations (Iannaccone 1992, Berman 2000, Carvalho 2013). Our data allow us to make progress on this distinction. Standard phone calls, which require another person, are more likely to reflect outward-facing considerations, such as social expectations or awareness that others may not answer during prayer. In contrast, calls to special ‘short code’ numbers (which are used to check account balances and the like) are more private, and arguably more likely to reflect internal motivations. Both decline during Maghrib, but voice calls drop more sharply, suggesting that it is not just outward-facing factors that cause the Maghrib dip in phone calls. The Maghrib dip thus captures both inward and outward-facing aspects of religious practice.

The Maghrib dip is particularly useful because it offers an unobtrusive measure of religious adherence. It is passively collected–in the sense that an individual does not have to actively express their opinions in a survey–and so is more likely to reflect actual behaviour. Moreover, unlike surveys, which fail in periods of instability, the Maghrib dip remains observable even in conflict zones.

Finally, the granularity of this new measure enables analysis at both individual and aggregate levels, across space and time. These features transform it into a dynamic, high-resolution metric, allowing us to study how religious adherence responds to external shocks, as illustrated in the case studies below.

Case study 1: Religiously-motivated insurgent violence reduces religiosity

Violence can affect religious observance in a number of ways. First, violence may increase religiosity. Threats of conflict may reinforce social and religious norms (Henrich et al. 2019), and conflict-driven uncertainty can push people toward religious solace (Pargament et al. 1998). Trauma arising from conflict may deepen faith (Mill et al. 2024) and create a desire for certainty (Callen et al. 2014), while conflict between religious groups can sharpen divisions and strengthen one’s own religiosity (Atkin et al. 2021). On the other hand, violence, especially when carried out in the name of a political ideology linked to religion, could have the opposite effect, similar to how civilian casualties undermine support for insurgents (Condra and Shapiro 2012). Within fragmented insurgencies, such violence may provoke backlash, undermining religious commitment rather than reinforcing it.

To study this relationship, we link our mobile phone data to 95,231 geo-coded violent incidents for the period April 2013 to December 2014, categorising them into four groups: insurgent violence (e.g. direct attacks, IED explosions, assassinations), other insurgent activities (e.g. threats, recruitment, unexploded ordnance), state-led violence (e.g. airstrikes, direct fire), and other state-led actions (e.g. detentions, arrests, intelligence gathering).

We find that religious adherence declines in response to religiously motivated violence perpetrated primarily by Islamist insurgents. This decline follows direct exposure to insurgent violence, but not the threat of it. Anticipated violence—threats or unrealised attacks like unexploded IEDs—has no measurable effect. This is consistent with backlash resulting from direct exposure to war’s destructive effects (Dell and Querubin 2018). In our case, we find that the backlash manifests itself in reduced adherence: it is the immediate experience of religious violence by insurgents—not the mere possibility of it—that drives this response.

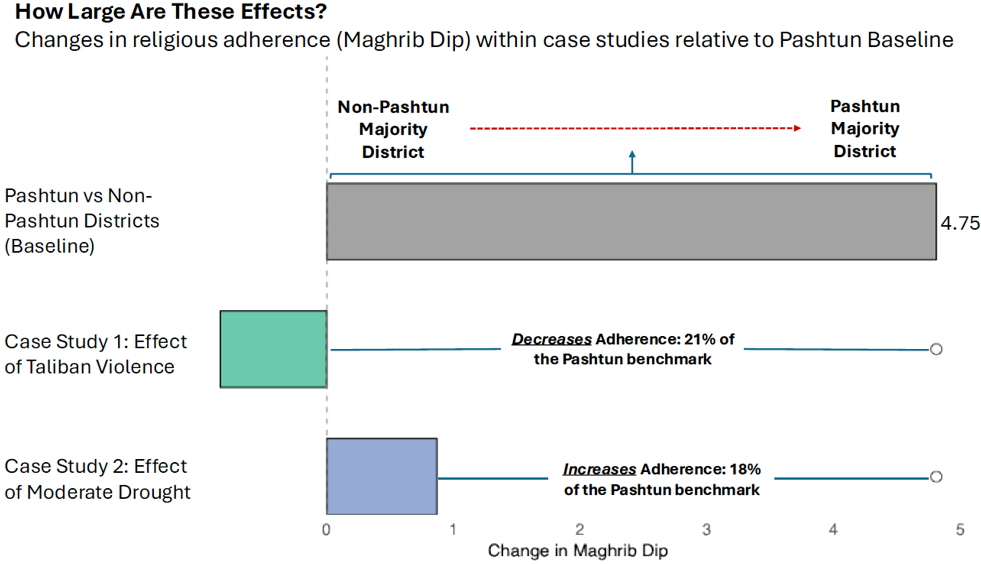

To provide some context for the magnitude of the effect, we benchmark it against known religious differences. In Figure 2, we saw that Pashto-speaking districts, which are typically more conservative, exhibit a much larger Maghrib dip. As seen in Figure 4, moving from a district-month at the 50th percentile of insurgent violence to the 90th percentile produces a decline in religiosity equivalent to 21% of the gap between a conservative, plurality-Pashtun district and a less conservative, non-Pashtun-dominated district (which is highlighted by the grey bar).

Figure 4: Effect sizes within case studies

Notes: The Maghrib Dip quantifies the relative decline in call volume around Maghrib by taking the difference between call volume in the 30 minutes before and after the prayer and dividing it by their average.

This pattern is specific to insurgent-led violence. State-led violence has no measurable impact on religiosity, suggesting that it is not conflict itself, but the fact that it is perpetrated by an Islamist political organisation that provokes this response.

Case study 2: Climate-induced income shocks increase religiosity

Similar to violence, economic distress created by climate shocks could affect religious observance in a variety of ways. On one hand, hardship may increase religious adherence by lowering the opportunity cost of participation (Azzi and Ehrenberg 1975), strengthening reliance on religious communities for social insurance (Iannaccone 1992, Berman 2000, Chen 2010), or providing psychological stability in times of distress. On the other hand, it may weaken religiosity if individuals lose faith when divine protection appears absent (Auriol et al. 2020). We examine this relationship by using the Standard Precipitation-Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) to measure climate shocks and tracking changes in religious adherence through the aggregated ‘Maghrib dip’ at a granular 10 km x 10 km grid-cell level.

We find that climate-induced economic hardship increases religious adherence. To quantify this effect, we compare the impact of SPEI on the Maghrib dip to the effect of being in a predominantly Pashtun area. To benchmark the size of this effect (Figure 4), we estimate that a moderate drought raises religious adherence by about 18% of the magnitude of the ethnic gap between Pashtun-majority areas and those where another group is the plurality. These effects are strongest in rainfed croplands without irrigation, precisely where droughts impose the most severe economic consequences. This pattern confirms that it is indeed economic distress that drives the increase in religious adherence.

Why does economic distress lead to greater religious adherence? Our evidence suggests a psychological coping mechanism rather than changes in opportunity costs or a social insurance motive. We find that droughts during the agricultural growing season increase religious adherence during the growing season, and again after harvest. However, there is no increase during the harvest itself. We interpret the lack of harvest season effects as evidence that the opportunity cost of time is not the primary mechanism linking climate and religious adherence. By contrast, the response in the growing season and after the harvest tells us that prayer suggests two comforting roles: a plea for divine intervention right when shocks hit and a means of coping once losses are realised after harvest. We also dig deeper into this effect and find that individuals who were more devout at baseline become even more adherent during times of climate-induced economic distress, consistent with the idea that religiosity serves as a coping mechanism in hardship.

Implications for future research on technology use and religiosity

The Maghrib dip offers a novel perspective on religious adherence, which provides a scalable, cost-effective complement to traditional surveys. Unlike conventional measures, it remains observable in conflict zones and other settings where direct data collection is infeasible; it is very geographically granular and available in near real-time. By comparing more publicly visible voice calls with less observable activity, it also allows us to assess whether religious adherence is driven by social enforcement or personal conviction. This measure adds to recent work on novel religiosity metrics, such as Livny (2021) using satellite imagery of Ramadan lights, and Pope (2024) using smartphone data to track church attendance.

We demonstrate the value of this measure through two applications. First, we show that Taliban attacks reduce religious observance, while unrealised attacks and violence perpetrated by the more secular state have no discernible effect. Second, we find that adverse climate shocks increase religious observance, particularly in rainfed agricultural areas where the economic consequences are most severe. These contrasting effects reveal how different types of shocks shape religiosity in distinct ways.

While our empirical focus is Afghanistan, this approach can likely be used more widely. It could be used to examine how religious adherence interacts with socioeconomic factors (such as education and technological change) or institutional dynamics (such as corruption and governance). Though we rely on mobile phone transactions—Afghanistan’s most widely used digital technology—other digital trace data, such as social media, could serve as alternative sources in different contexts.

More broadly, our approach illustrates how patterns of technology use and disuse can offer a new, quantitative perspective on religious behaviour. We hope this work encourages further research into how digital data can enhance the study of religion and social behaviour.

References

Allport, G W and J M Ross (1967), “Personal religious orientation and prejudice”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5(4): 432–443.

Atkin, D, E Colson-Sihra, and M Shayo (2021), “How do we choose our identity? A revealed preference approach using food consumption”, Journal of Political Economy, 129(4): 1193–1251.

Auriol, E, J Lassébie, A Panin, E Raiber, and P Seabright (2020), “God insures those who pay? Formal insurance and religious offerings in Ghana”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(4): 1799–1848.

Azzi, C and R Ehrenberg (1975), “Household allocation of time and church attendance”, Journal of Political Economy, 83(1): 27–56.

Barfield, T J (2022), "Afghanistan: A cultural and political history", Princeton University Press.

Becker, S O, J Rubin, and L Woessmann (2021), “Religion in economic history: A survey”, in The Handbook of Historical Economics, edited by A Bisin and G Federico, Academic Press: 585–639.

Berman, E (2000), “Sect, subsidy, and sacrifice: An economist’s view of ultra-Orthodox Jews”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(3): 905–953.

Brenner, P S (2011), “Exceptional behavior or exceptional identity? Overreporting of church attendance in the US”, Public Opinion Quarterly, 75(1): 19–41.

Brenner, P S and J DeLamater (2016), “Lies, damned lies, and survey self-reports? Identity as a cause of measurement bias”, Social Psychology Quarterly, 79(4): 333–354.

Bryan, G, J J Choi, and D Karlan (2021), “Randomizing religion: The impact of Protestant evangelism on economic outcomes”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 136(1): 293–380.

Campante, F and D Yanagizawa-Drott (2015), “Does religion affect economic growth and happiness? Evidence from Ramadan”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(2): 615–658.

Carvalho, J-P (2013), “Veiling”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(1): 337–370.

Chen, D L (2010), “Club goods and group identity: Evidence from Islamic resurgence during the Indonesian financial crisis”, Journal of Political Economy, 118(2): 300–354.

Condra, L N and J N Shapiro (2012), “Who takes the blame? The strategic effects of collateral damage”, American Journal of Political Science, 56(1): 167–187.

Dell, M and P Querubin (2018), “Nation building through foreign intervention: Evidence from discontinuities in military strategies”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133(2): 701–764.

Dube, O, J E Blumenstock, and M Callen (2025), “Measuring religion from behavior: Climate shocks and religious adherence in Afghanistan”, Unpublished manuscript.

Hadaway, C K, P L Marler, and M Chaves (1998), “Overreporting church attendance in America: Evidence that demands the same verdict”, American Sociological Review, 63(1): 122–130.

Henrich, J, M Bauer, A Cassar, J Chytilová, and B G Purzycki (2019), “War increases religiosity”, Nature Human Behaviour, 3(2): 129–135.

Iannaccone, L R (1992), “Sacrifice and stigma: Reducing free-riding in cults, communes, and other collectives”, Journal of Political Economy, 100(2): 271–291.

Livny, A (2021), “Can religiosity be sensed with satellite data? An assessment of luminosity during Ramadan in Turkey”, Public Opinion Quarterly, 85(S1): 371–398.

McCleary, R M and R J Barro (2006), “Religion and economy”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(2): 49–72.

Mill, W, T Ebert, J B Berkessel, T Jonsson, S Lehmann, and J E Gebauer (2024), “War causes religiosity: Gravestone evidence from the Vietnam Draft Lottery”, SocArXiv.

Pargament, K I, B W Smith, H G Koenig, and L Perez (1998), “Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors”, Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 37: 710–724.

Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures (2022), “Global Religious Futures Project”.

Pope, D G (2024), “Religious worship attendance in America: Evidence from cellphone data”, Unpublished manuscript.

Siddiqui, A H (2005), "Kitab al-Salaat (The Book of Prayers)", 51: 1098, 1101.

Weber, M (1905), "The Protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism", Scribners.