Artificial Intelligence, particularly Generative AI, is rapidly transforming labour markets worldwide. While its adoption has sparked optimism about its potential to spur productivity gains, it also raises concerns of widespread job displacement. The implications for developing economies are particularly complex, as AI could both widen existing inequalities and create new opportunities for economic growth.

A framework is crucial for understanding AI’s labour market impact

To measure the potential impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on labour markets, economic research has widely relied on the so-called ‘task framework’ (Acemoglu and Restrepo 2019). This approach views occupations as bundles of tasks, some of which AI can perform efficiently, such as text analysis, coding, and data processing. Recent studies have identified which tasks can be performed by AI and developed measures of ‘occupational AI exposure’ (Felten et al. 2021, 2023). While this approach provides valuable insights into which occupations are highly exposed to AI, it does not speak directly to whether AI may ultimately benefit workers employed in those jobs or displace them.

In recent research, we move beyond simple AI exposure measures to introduce an index of ‘AI complementarity,’ capturing the likelihood that AI will enhance the skills of some workers rather than replace them (Pizzinelli et al. 2024). This complementary measure incorporates broader occupation-specific factors that influence the likelihood of benefiting from AI adoption. These factors include responsibility for others’ health, the criticality of independent decision-making, need for in-person interactions, physical work environments, and required educational and technical training needed for the role. By expanding the task framework with our proposed measures, occupations can be grouped into three categories: those at high risk of labour substitution (high exposure and low complementarity, or HELC), those likely to experience productivity and wage boosts (high exposure and high complementarity, or HEHC), and those less affected by AI adoption (low exposure, or LE).

AI’s impact on labour market will vary across the world

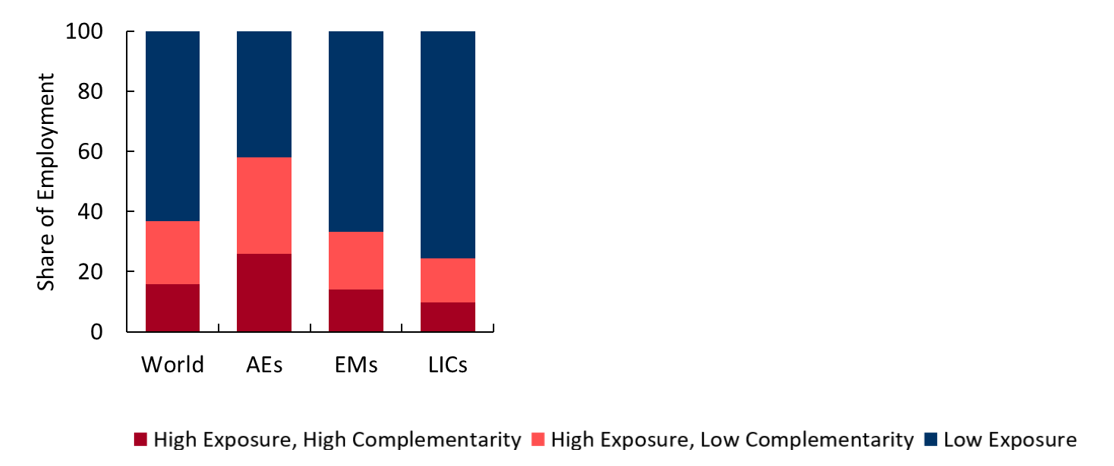

Our findings indicate that 40% of global employment is exposed to AI, but the risks and opportunities vary by country. In advanced economies, nearly 60% of jobs could be affected, with an even split between AI complementing or substituting workers. By contrast, AI exposure in emerging and low-income economies is lower (40% and 26%, respectively), indicating that the potential of AI to benefit and hurt workers is also more limited.

Figure 1: Employment shares by AI exposure and complementarity

Note: Country labels use International Organization for Standardization (ISO) country codes. ISCO stands for International Standard Classification of Occupations. AEs = advanced economies; EMs = emerging markets; LICs = low-income countries; World = all countries in the sample. Share of employment within each country group is calculated as the working-age-population-weighted average. Source: Cazzaniga et al. (2024).

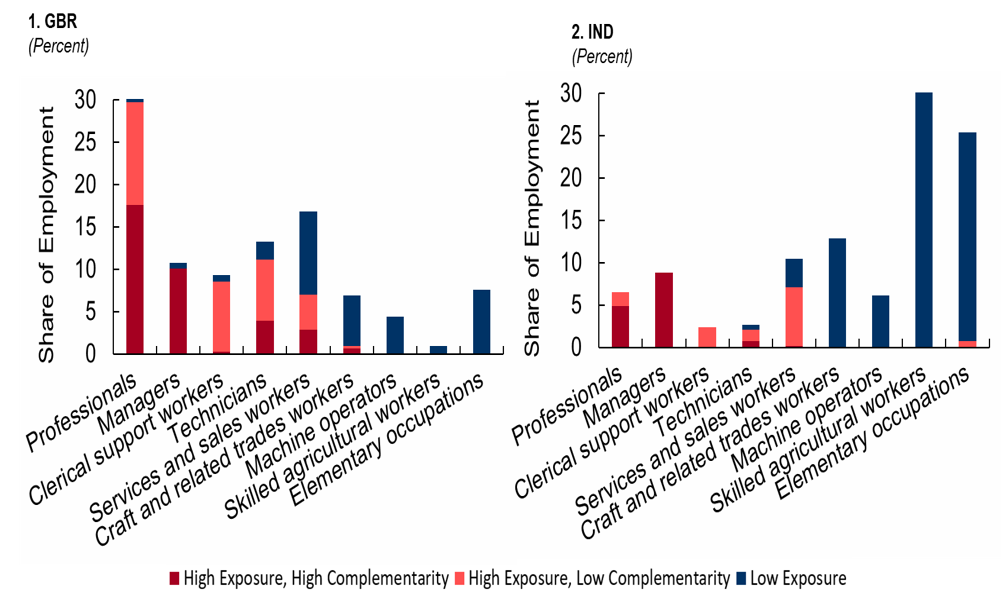

A key factor explaining this variation is differences in economic structure and the occupational composition of employment across countries (Figure 2). Advanced economies—such as the UK—tend to have a higher share of workers in professional, managerial, and technical occupations with high AI exposure. These jobs are typically split between those benefiting from AI complementarity (e.g. professionals and managers) and those at risk of displacement (e.g. clerical support workers and technicians). By contrast, many developing economies, such as India, still have a higher share of manual and agricultural work employment, which has limited exposure to AI.

As a result, for developing economies, the patterns of exposure to AI suggest two key challenges: (1) higher barriers to benefits but lower immediate challenges, and (2) risk of falling behind due to the increase in inequality across countries. If AI adoption remains concentrated in high-income economies, productivity gains could be unequally distributed, exacerbating economic disparities between countries.

Figure 2: Employment shares by AI exposure and complementarity

Note: Country labels use International Organization for Standardization (ISO) country codes. ISCO stands for International Standard Classification of Occupations. AEs = advanced economics; EMs = emerging markets; LICs = low-income countries; World = all countries in the sample. Share of employment within each country group is calculated as the working-age-population-weighted average. Source: Cazzaniga et al (2024).

While many developing economies remain less exposed to AI, the effects of AI are already playing out in countries at the frontier of adoption. Evidence from the US, for example, shows how AI is reshaping job demand, particularly for lower-complexity occupations. Using US Census Bureau data on firms' AI adoption in 2018 as a proxy for AI penetration at the commuting zone (CZ) level, analysis reveals that vacancies in HELC occupations expanded at a slower pace in CZs with greater AI adoption. In contrast, vacancies in HEHC occupations remained stable or even increased in these areas. We estimate that a one-standard-deviation increase in AI adoption in 2019—equivalent to 0.18 percentage points, comparable to the difference between Boston, Massachusetts, and Portland, Oregon—was associated with a 0.4 percentage point decline in the share of HELC vacancies between 2019 and 2023. These findings suggest that AI adoption is reshaping job demand, disproportionately affecting lower-complementarity roles while having a more neutral or positive impact on high-complementarity occupations.

AI preparedness reforms are needed to ensure an inclusive AI-driven world

Across the world, in both advanced economies and emerging markets, businesses face strong pressures to speedily integrate AI in their production processes and delivery of services. Policy action is needed on multiple fronts to facilitate an inclusive and labour-friendly AI transition, ranging from scaling up essential infrastructure to creating an investment-friendly environment, adapting regulatory frameworks to the AI era and investing in workers’ skills. While such interventions require a comprehensive long-term strategy, it is also crucial for policymakers to identify priority areas for their own countries.

To help countries craft the right policies, the IMF has developed an AI Preparedness Index (Cazzaniga et al. 2024) that measures readiness in areas such as digital infrastructure, human capital and labour-market policies, innovation and economic integration, and regulation and ethics.

On human capital and labour-market policies, for example, the index evaluates elements such as years of schooling and job-market mobility, as well as the proportion of the population covered by social safety nets. The regulation and ethics dimension assesses the adaptability to digital business models of a country’s legal framework and the presence of strong governance for effective enforcement.

Using the index, IMF staff assessed the readiness of 125 countries. Their findings reveal that wealthier countries, including advanced and some emerging market economies, tend to be better equipped for AI adoption than low-income countries, though there is considerable variation across countries. Singapore, the US, and Denmark rank highest in the overall index, based on their high scores in all four categories tracked. Meanwhile, the countries that rank the highest among emerging market and developing economies are China and Malaysia.

Guided by the insights from the AI Preparedness Index, advanced economies should prioritise AI innovation and integration while developing robust regulatory frameworks. This approach will cultivate a safe and responsible AI environment, helping maintain public trust. For emerging market and developing economies, the priority should be laying a strong foundation through investments in digital infrastructure and a digitally competent workforce. Beyond labour market implications, AI also holds promise for improving education and healthcare in low-income developing countries, offering new opportunities for inclusive development.

Policy implications for AI in global labour markets

AI is reshaping the global labour market, but its benefits and risks are not evenly distributed. The extent to which countries can leverage AI to the benefit of all depends on how well prepared they are to facilitate the economy-wide adoption of AI-based technologies. Appropriate legal frameworks that promote investments in digital innovation while addressing the risks inherent in widespread AI adoption remain essential, especially in advanced economies. In emerging market and developing economies that may be less immediately exposed to the risks of AI, policymakers should prioritise investing in essential digital infrastructure and equip their labour force, especially those about to enter the labour market, with the necessary skills to fill the jobs that are expected to be in higher demand.

Editor’s note: The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and should not be attributable to the International Monetary Fund, its Executive Board, or its management.

References

Acemoglu, D. and Restrepo, P. (2019). "Artificial intelligence, automation, and work." The Economics of Artificial Intelligence: An Agenda, pp. 197–236. University of Chicago Press.

Cazzaniga, M., Jaumotte, F., Li, L., Melina, G., Panton, A. J., Pizzinelli, C., Rockall, E. J. and Tavares, M. M. (2024). "Gen-AI: Artificial intelligence and the future of work." Unpublished manuscript.

Felten, E., Raj, M. and Seamans, R. (2021). "Occupational, industry, and geographic exposure to artificial intelligence: A novel dataset and its potential uses." Strategic Management Journal, 42(12): 2195–2217.

Felten, E., Raj, M. and Seamans, R. (2023). "How will language modelers like ChatGPT affect occupations and industries?" Unpublished manuscript.

Pizzinelli, C., Panton, A., Tavares, M. M., Cazzaniga, M. and Li, L. (2024). "Labor market exposure to AI: Cross-country differences and distributional implications." Unpublished manuscript.