A cap on corporate loan interest rates in Bangladesh led to an increase in lending–without rationing credit to riskier borrowers–indicating banks have substantial upfront market power. What are the implications for interest rate regulation in developing countries?

Firms in countries with underdeveloped financial and legal systems encounter high costs of external financing (Beck et al. 2005). Capping interest rates on loans is a tool widely used by regulators in developing countries to stimulate investment, particularly for manufacturing export goods firms (Ferrari et al. 2018).[1] Opponents of these policies cite several potential drawbacks, including that lenders may respond by shifting credit away from the riskiest borrowers to limit their losses. However, little is known about the causal effects of cap policies on corporate loans, especially in developing countries without a mature capital market.

Our research using credit registry data and a policy experiment in Bangladesh shows that corporate loan rate caps can expand credit access when banks wield market power in offering short-term loans (Kuroishi et al. 2025). Specifically, we found that a 100 basis point drop in rates increased lending by 37% at branches previously charging rates above an interest rate cap imposed by the Central Bank. This offers evidence into how price regulation can mitigate market power distortions in corporate banking without rationing credit to riskier or non-exporting firms.

The effect of corporate loan rate caps on credit provision

Economic theories of corporate lending emphasise the role of relationship lending, through which banks can charge existing customers higher loan interest rates if borrowers face switching costs (Petersen and Rajan 1995). But if the banking sector features market power for new as well as continuing borrowers, how would an interest rate cap affect lending?

When banks can charge interest rates above competitive levels, they may restrict credit supply to maximise profits. Interest rate caps can have two opposing effects. On the one hand, caps can increase lending by forcing banks to lower rates, making loans more affordable and increasing borrower demand. In contrast, caps may decrease lending if they prevent banks from charging rates that compensate for lending risks and relationship-building costs. The key theoretical insight is that caps are more likely to increase credit supply when banks have significant ex ante market power but do little to limit banks’ ability to extract future profits from established customer relationships. We test which force dominates by considering a policy environment where both forms of bank market power are likely to be present.

Studying Bangladesh’s 2009 ceiling on corporate loan rates

In April 2009, Bangladesh Bank (the Central Bank) imposed a maximum annualised interest rate of 13% on private business loans to large- and medium-scale industrial firms. Upon implementation, over half of aggregate bank lending to the private sector was subject to the cap. Prior to this date, there was no direct regulation of rates charged on industrial loans in Bangladesh.

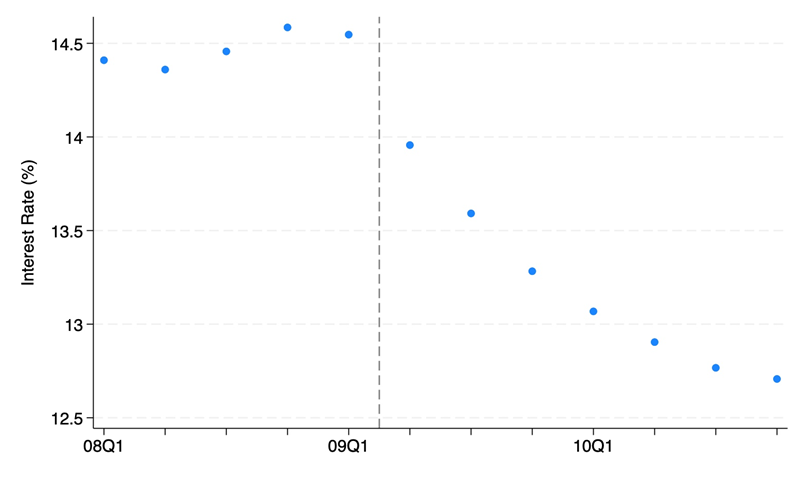

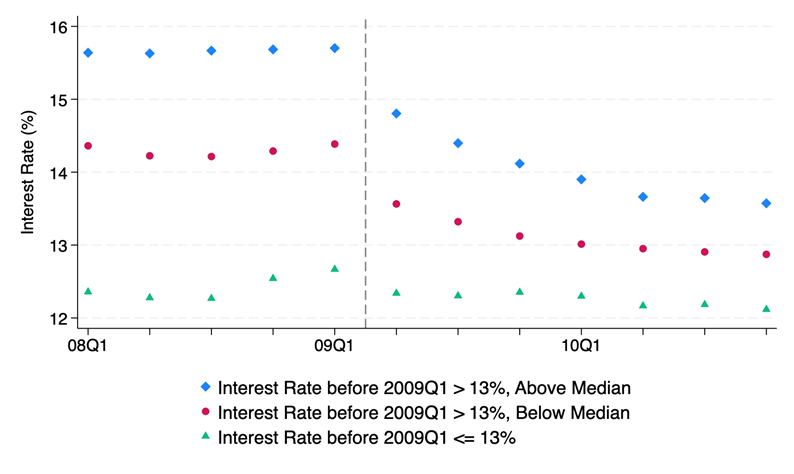

Using credit registry data from Bangladesh Bank, Figure 1 (Panel A) shows that average branch-level interest rates charged on regulated loans sharply fell by 50 basis points in 2009Q2 after the cap enactment, and continued to fall during the two years the rate ceiling was in place.[2] Figure 1 (Panel B) demonstrates that the drop in interest rates was concentrated among branches more exposed to the reform because they were previously charging rates well above the 13% threshold.

Figure 1: Time path of branch-level interest rates around the cap reform

Panel A: Average branch-level interest rates

Panel B: Average rates by branch cap exposure

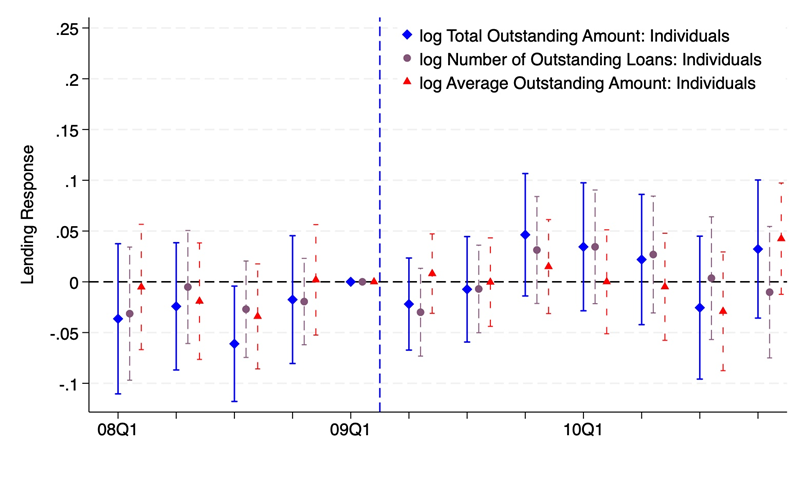

The evidence in Figure 1 suggests a research design to tease out causal effects of the rate ceiling on credit provision. In Figure 2, after holding fixed any balance sheet shocks specific to the parent bank, we compare lending patterns for branches which were charging loans at relatively higher interest rates above the 13% cap to a control group of branches which were already charging rates below 13%. Lending steadily expanded in terms of both loan amounts and the number of loans outstanding (Panel A). A 100 basis point drop in interest rates induced by the cap led to a 37% increase in loan dollars outstanding, a 15% increase in the number of loan contracts, and a 19% increase in the average loan amount. We did not uncover any negative effects on credit provision to individual borrowers for whom there was no interest rate regulation (Panel B). This indicates that banks did not try to recoup lost profits by raising prices on unregulated loan products.

Figure 2: Bank branch lending responses to the interest rate cap

Panel A: Response of cap-regulated loans to corporate borrowers

Panel B: Response of cap-unregulated loans to individual borrowers

How did banks respond to interest rate caps?

We observed no post-cap change in delinquency rates or in the fraction of loans unsecured by physical collateral, suggesting branches did not reallocate credit away from riskier borrowers. We also uncovered no differential responses of branches to the cap according to common measures of marginal costs of funding, including pre-cap non-performing loan rates, the fraction of loans not secured by physical collateral, or deposit rates. If banks have market power over deposits, then it will be easier for them to pass through the costs of a rate cap on loans to their depositors (Drechsler et al. 2017). Ultimately, we found no evidence of branches lowering their deposit rates, likely due to statements made by the Central Bank encouraging banks to keep deposit rates elevated.

Additional evidence on market power in Bangladesh’s banking sector

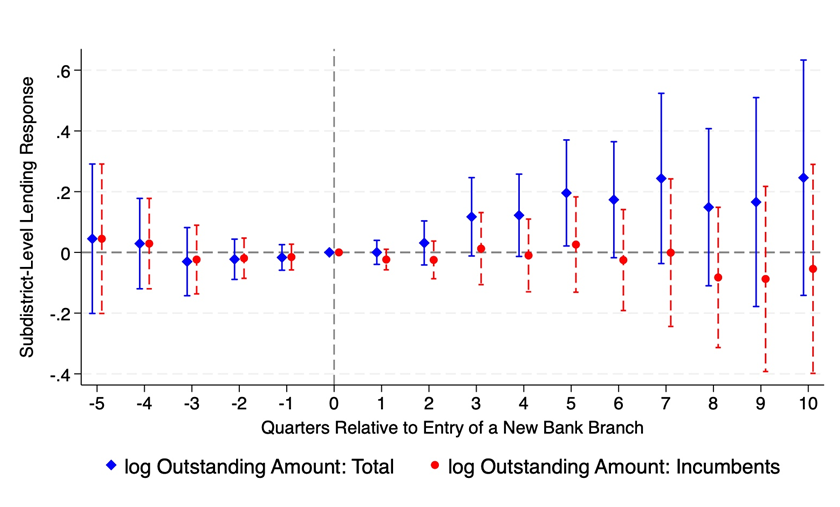

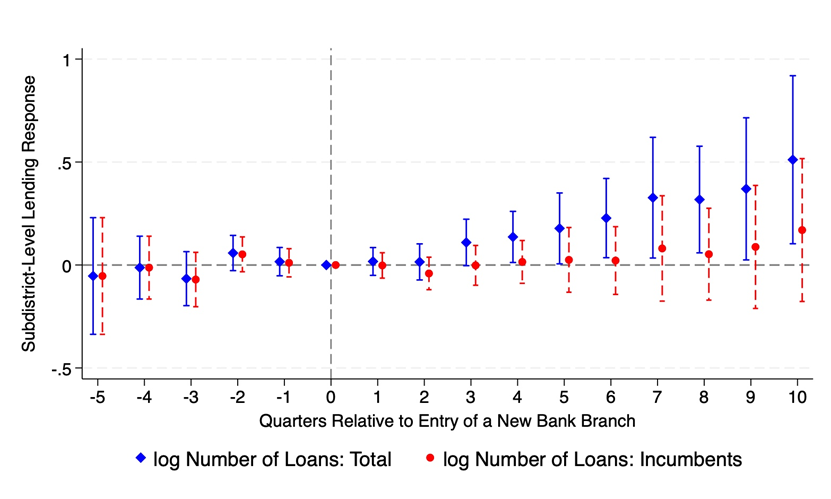

We provide direct evidence that banks exhibit market power by examining how local interest rates and lending respond after banks open new branches in the same sub-district. We conducted two sets of tests. In the first, we matched each parent bank to its closest competitor in terms of its pre-cap balance sheet size and the industrial sector to which it offered the largest share of loans. In doing so, we found that the entry of a close competitor had no influence on a branch’s rate setting or loan provision. In the second test, we show that the entry of any new branch into a sub-district had no discernible effect on total lending by incumbent branches but led to an overall increase in total lending in the sub-district (see Figure 3).[3] Together, the results from our two tests point to banks in Bangladesh facing imperfect competition for new borrowers.

Figure 3: Effects of new branch entry on local corporate credit provision

Panel A: Outstanding loan amount

Panel B: Number of outstanding loan contracts

Implications for interest rate regulation in developing countries

Our results suggest that ex ante market power contributes to significant underprovision of bank loans to firms, which interest rate caps can help address. Our finding of a lack of credit rationing to riskier borrowers may be because the 2009 Bangladesh cap applied to large firms as opposed to small and medium enterprises which are harder to screen for creditworthiness but more likely to face financing constraints.[4] Moreover, nationwide rate caps can also dampen the power of monetary policy to stabilise inflation, or reduce long-run incentives of banks to enter certain markets due to perceived regulatory risks.

Given the distortions rate caps may introduce at the macroeconomic level, more research is needed to establish the aggregate welfare implications of interest rate regulation. Several developing countries, including Bangladesh, the Dominican Republic, and Vietnam, responded to the COVID-19 crisis with a fresh round of rate cap policies to prop up firm investment during a period of diminished trade (IMF 2021, Bangladesh Bank 2022). Quantifying interest rate markups charged on loans to different types of borrowers will help guide policymakers in their decisions on whether and how to implement future rate caps.

References

Bangladesh Bank (2022), “Impact assessment of interest rate caps and potential policy options: Bangladesh perspective”.

Beck, T, A Demirgüç-Kunt, and V Maksimovic (2005), “Financial and legal constraints to growth: Does firm size matter?”, Journal of Finance, 60(1): 133–177.

Benmelech, E and T J Moskowitz (2010), “The political economy of financial regulation: Evidence from U.S. state usury laws in the 19th century”, Journal of Finance, 65(3): 1029–1073.

Burga, C, R Nivin, and D Yamunaqué (2022), “Lending rate caps and credit reallocation”, Central Bank of Peru Working Paper Series.

Cuesta, J I and A Sepulveda (2021), “Price regulation in credit markets: A trade-off between consumer protection and credit access”, Unpublished manuscript.

Drechsler, I, A Savov, and P Schnabl (2017), “The deposits channel of monetary policy”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(4): 1819–1876.

Ferrari, A, O Masetti, and J Ren (2018), “Interest rate caps: The theory and the practice”, World Bank.

International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2021), “Policy responses to COVID-19”.

Kuroishi, Y, C LaPoint, and Y Miyauchi (2025), “Interest rate caps, corporate lending, and bank market power: Evidence from Bangladesh”, Unpublished manuscript.

Melzer, B T and A Schroeder (2017), “Loan contracting in the presence of usury limits: Evidence from automobile lending”, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Office of Research.

Petersen, M A and R G Rajan (1995), “The effect of credit market competition on lending relationships”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(2): 407–443.

Rigbi, O (2013), “The effects of usury laws: Evidence from the online loan market”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(4): 1238–1248.

[1] In advanced economies, rate ceilings are often framed as anti-usury laws restricted to consumer credit (Benmelech and Moskowitz 2010), such as online instalment (Rigbi 2013) or automobile loans (Melzer and Shroeder 2017).

[2] We focus our analysis on private banks, which include 39 private commercial banks and nine foreign commercial banks. Our results are similar regardless of whether we exclude from our sample the eight banks which adhere to Islamic finance principles.

[3] In both sets of tests for ex ante market power we use a variety of modern difference-in-differences estimators to account for the staggered timing of branch entry across geographic areas. We estimate similar results regardless of whether we include in the control group areas or branches which do not experience new entrants.

[4] By studying similar cap policies for consumer loans in Chile and small firm loans in Peru, Cuesta and Sepulveda (2021) and Burga et al. (2022), respectively, show evidence of credit rationing to riskier borrowers.