Slum upgrading programmes improve living conditions for low-skilled residents, but potentially at the cost of formal development and inefficient land allocation. Evidence from Indonesia reveals that these costs are largest close to the city centre, suggesting that slum upgrading efforts be targeted in less-developed regions of the city.

Many cities in developing countries are undergoing mass urbanisation. Amidst housing shortages, slums have served as entry points for migrants looking to move to cities in search of employment and upward mobility. The UN estimates that more than one billion people currently live in slums, with an additional two billion expected to relocate to slums in the next three decades (UN 2023).

On-site slum upgrading has become a popular policy to improve shelter and neighbourhood conditions without relocating slum residents. These programmes have thus far been implemented in numerous developing countries, including India, Brazil, and Kenya. However, policymakers worry that upgrading slums may prolong their lifespan beyond what would otherwise be expected. As a city expands, and centrally located land becomes scarce, preserving slums at the expense of formal developments may lead to land misallocation. The trade-off between the short-run benefits to slum residents, and the long-run opportunity costs of land use, lies at the heart of the policy debate on whether and where to upgrade slums.

Slum upgrading delays formalisation in programme areas

We shed light on the long-term impacts of slum upgrading by studying one of the world’s largest programmes of its kind, the Kampung Improvement Program (KIP) in Jakarta, Indonesia (Harari and Wong 2025). (Kampung is a colloquial term used in Indonesia to describe traditional urban villages. We will use the terms slums and kampungs interchangeably.) Between 1969 and 1984, KIP provided basic public goods and verbal non-eviction guarantees to five million slum dwellers living on one-fourth of Jakarta’s land. One challenge in estimating the impacts of the programme is selection bias, as KIP targeted slums most in need; we address this through several localised comparisons. Our study relies on the assumption that pre-KIP differences have diminished over time and nearby locations now experience similar shocks.

Using high-resolution policy maps and data on 19,515 locations around Jakarta, which includes 2015 assessed land values, building heights, and a photographic sample to characterise informality, we perform three kinds of comparisons. We begin with a comprehensive, city-wide sample and compare KIP and non-KIP locations within the same hamlet (a unit similar to US census block groups). Next, we limit our sample to historical kampungs that existed before KIP, comparing those that received upgrades to those that did not, within the same locality (similar to US census tracts). Finally, we use a boundary discontinuity approach, examining areas within 200 metres of KIP boundaries.

In KIP areas, we find that land values are 10% lower, buildings are 7 percentage points less likely to be high-rises, and have 9% fewer floors on average. These effects are robust to our different specifications and have effect sizes as large as 40% of the control group means. This pattern aligns with concerns about delayed formalisation: while KIP neighbourhoods initially improved with upgrades (World Bank 1995), they remained informal, whereas non-KIP areas became formal, ultimately reversing market outcomes.

To quantify informality, we collected street view photos from a representative sample of locations across the city. In the 10% of places where Google Street View is not available, due to narrow slum streets or gated communities, we sent our field team to take pictures. Using this photographic database, we construct an informality index that ranks locations from 0 (very formal) to 4 (very informal) based on neighbourhood appearance. We find that KIP areas are more informal by 0.27 points (relative to a control group mean of 1.11). KIP areas are also more likely to have parcels that are not registered in the formal cadastral system and more fragmented land, as measured by parcel density.

The opportunity costs from delayed formalisation are more pronounced close to the city centre

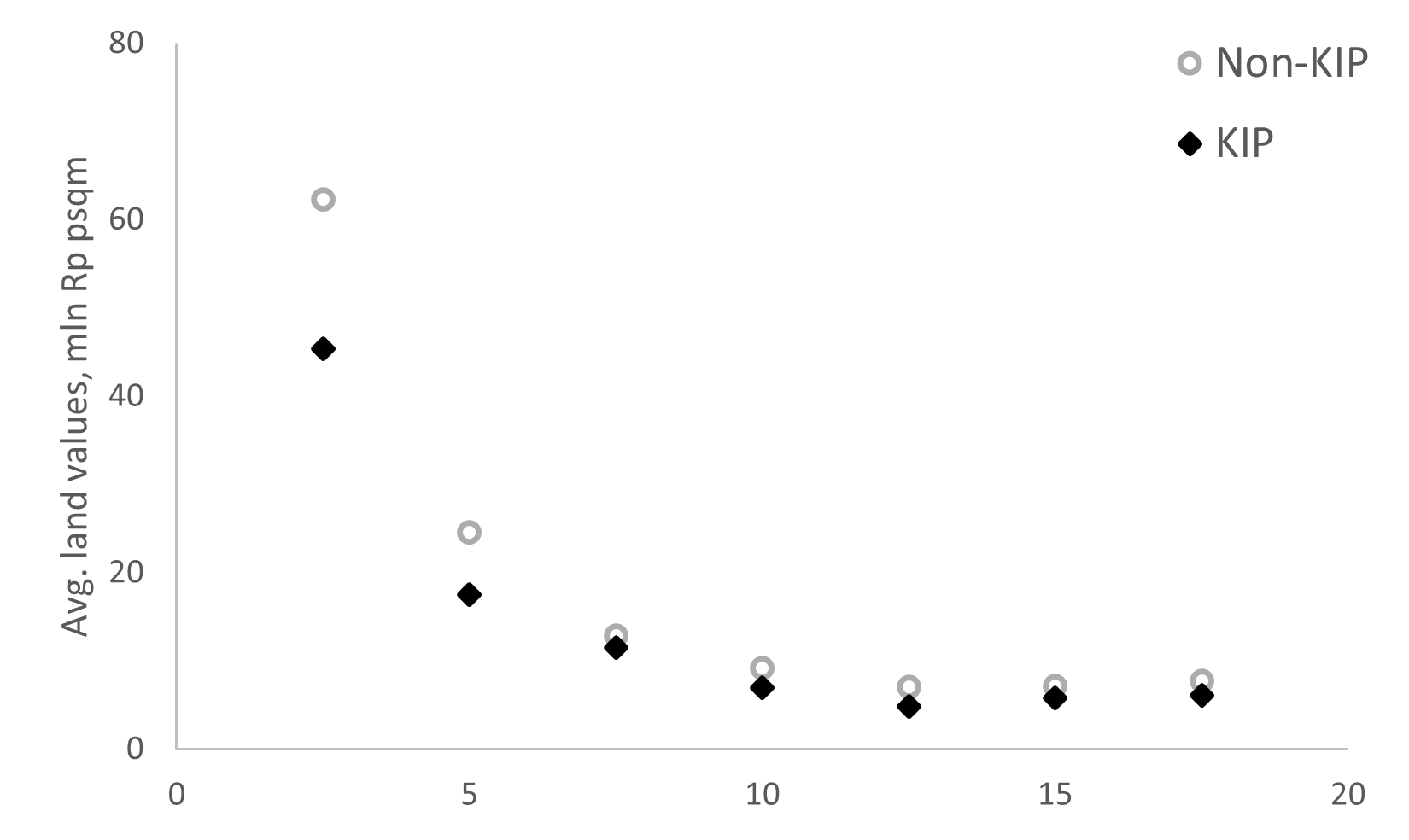

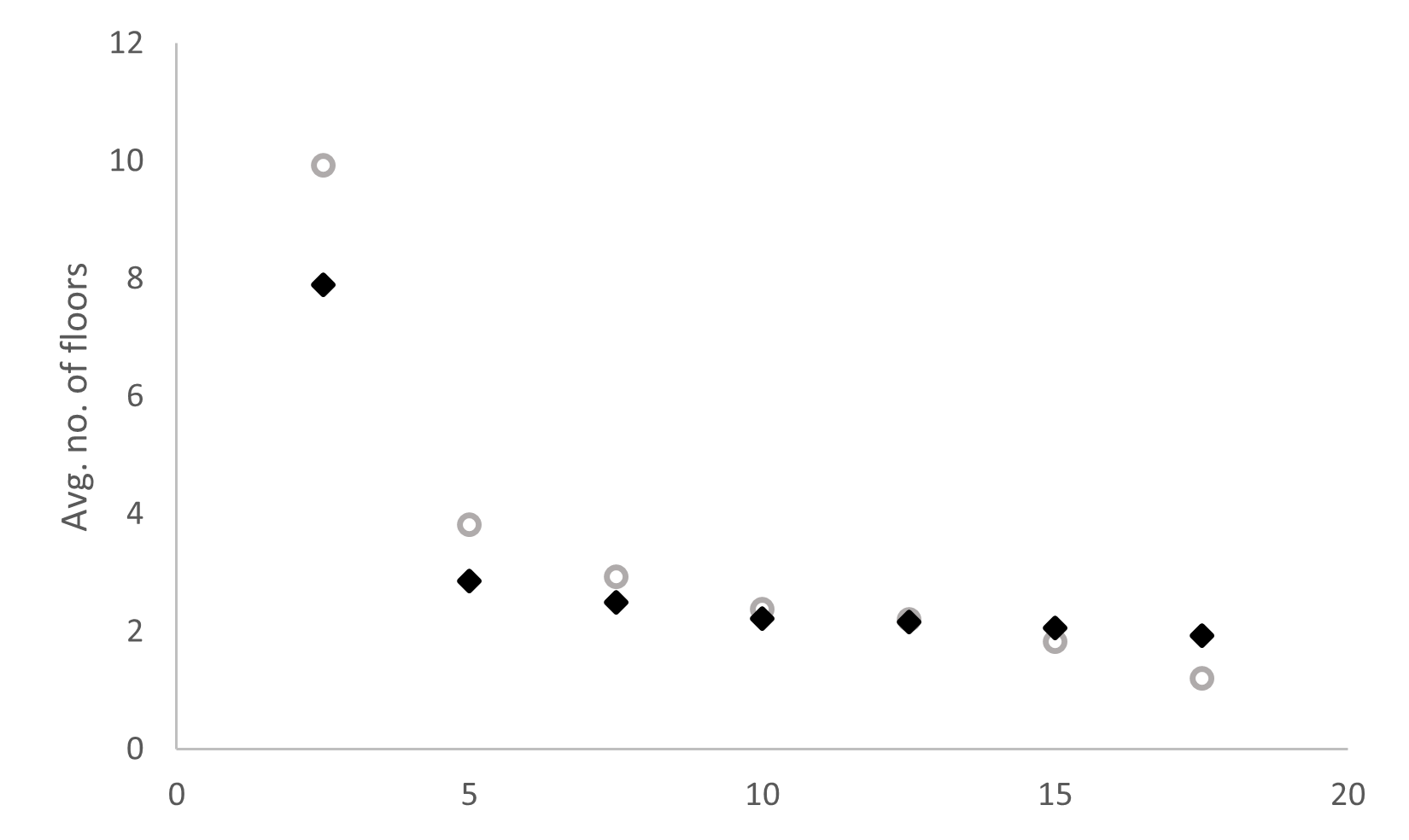

One key finding is that the most negative KIP estimates are in the centre of the city, where 44% of all upgraded areas are located (Figure 1). Intuitively, the opportunity costs from staying informal are greater close to the city centre, where the potential gains from redevelopment are the largest. We leverage the geographic scope of KIP and classify the city into centre, middle, and peripheral regions by distance to the central business district. Our estimates on land values for the three regions are -0.14, -0.10, and -0.09 in the centre, middle, and periphery, respectively. Similarly, our estimates on building heights are -0.13, -0.06, and -0.04, respectively.

Figure 1: Land values and building heights by KIP status and distance to the centre

Notes: Average land values (IDR million per square meter) and average number of floors by KIP status and distance to the city centre (in kilometres).

We examine the factors associated with the delayed formalisation of KIP areas, focusing on the role of physical upgrades. Using detailed policy maps, we analyse exposure to different types of KIP investments, such as paved footpaths and drainage canals. Our findings do not indicate differential effects on land values, aligning with the 15-year projected lifespan of these upgrades. Additionally, we assess concerns that improvements could make slums more attractive, leading to crowding and challenges related to land fragmentation and holdout issues. Based on cadastral map data, KIP areas contain 10 more parcels per unit area relative to the control group average. However, absent high-resolution, time-series population density data, we cannot conclusively determine whether KIP contributed to greater crowding. Our results withstand a series of robustness checks, easing concerns related to programme selection bias, persistence of slums, and spatial spillovers.

The distributional trade-offs of slum upgrading for high- vs low-skilled residents

To characterise the welfare implications of KIP, we develop a spatial equilibrium model featuring two types of residents, high- and low-skilled, and two housing market segments, informal and formal. We assume that markets are well-functioning within each segment, and that there are frictions associated with converting land from informal to formal.

Through the lens of the model, wedges in land values and heights between KIP and non-KIP reflect differences in amenities and formalisation costs. For instance, KIP upgrades and enhanced tenure security are reflected by improved informal amenities within KIP areas. For each non-KIP location, we construct a KIP counterpart such that the model-implied difference in equilibrium prices and quantities match the reduced-form estimates, with more pronounced effects in the centre. Through our counterfactuals, we quantitatively assess how KIP affects welfare. Our simulations find that, without KIP, there would be a boost in formal housing supply, benefiting high-skilled residents and displacing low-skilled residents to less desirable locations.

Benchmark estimates reveal a 3.3% city-wide welfare effect of completely removing KIP (i.e. all KIP locations inherit the same amenities and formalisation costs as their non-KIP counterparts). Strikingly, 78% of these gains are associated with KIP areas in the centre, echoing the reduced-form results. One simulation, combining the removal of KIP in the centre and relaxed height restrictions, akin to a zoning reform, preserves the gains to high-skilled workers while minimising the displacement of the low-skilled. Moreover, redistributing 5% of the formal land surplus to the low-skilled results in both groups gaining.

How should policymakers target slum upgrading programmes?

Beyond Indonesia, our findings offer insights on whether and where to implement slum upgrading efforts, as well as broader strategies for managing urban growth. Our welfare analysis suggests that spatial misallocation is most pronounced in centrally located KIP areas. Notably, a large share of the KIP programme area is outside the centre, and we find limited gains from removing KIP in those areas. Taken together, slum upgrading may offer an attractive cost-benefit trade-off in cities at earlier stages of development, similar to the middle and peripheral areas of Jakarta, where the opportunity costs of remaining informal are low. Furthermore, we highlight that urban transformation has significant distributional impacts, with low-income residents often being displaced without compensation.

Our findings echo that of recent research on urban development under weak property rights, underscoring misallocation and opportunity costs of land use in slums in Kenya and India (Henderson et al. 2020, Gechter and Tsivanidis 2023). We also complement the evidence on shelter provision and slum policy in developing countries (Michaels et al. 2021). Relative to alternative policy approaches, slum upgrading can be suitable for cities with scarce vacant land and limited resources to provide shelter at scale.

References

Gechter, M, and N Tsivanidis (2023), “Spatial spillovers from high-rise developments: Evidence from the Mumbai Mills,” Unpublished manuscript.

Harari, M, and M Wong (2025), "Slum Upgrading and Long-run Urban Development: Evidence from Indonesia," Unpublished manuscript.

Henderson, J V, T Regan, and A J Venables (2020), “Building the city: From slums to a modern metropolis,” The Review of Economic Studies, 88(3): 1157–1192.

Michaels, G, D Nigmatulina, F Rauch, T Regan, N Baruah, and A Dahlstrand (2021), “Planning ahead for better neighborhoods: Long-run evidence from Tanzania,” Journal of Political Economy, 129(8): 2112–2156.

UN (2023), "The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023: Goal 11 – Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable," United Nations Statistics Division.

World Bank (1995), "Enhancing the quality of life in urban Indonesia: The legacy of the Kampung Improvement Program," World Bank.