Benchmarking multi-dimensional in-kind programmes against cost-equivalent unconditional cash transfers reveals that cash can be more effective in improving consumption and asset accumulation.

On February 26, 2025, the US government cancelled 90% of all USAID contracts, amounting to more than USD$60 billion in US foreign assistance. These cuts appear to reflect a view that USAID's foreign assistance is not aligned with US taxpayer interests, inefficient, or both. One measure of the concern for inefficiency is the worry that a large share of funds is consumed by overheads. The concern for the share of foreign assistance that reaches its intended beneficiaries is a longstanding one, for charitable foundations (Gneezy et al. 2014) as well as the government. These concerns have animated an interest in providing assistance in the form of cash grants, as these can be delivered with minimal overheads relative to other, more complex forms of assistance.

But is this the right way to judge the efficiency of spending at USAID? What matters fundamentally is that the return on foreign assistance dollars is high. The President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) demonstrates the potential of overhead-heavy programmes to be cost-effective. Reauthorised in 2023 at an annual price tag of $6.9 billion (Moss and Kates 2023), PEPFAR is estimated to have saved 25 million lives since its inception in 2003 (George W. Bush Presidential Center 2023). While a substantial share of PEPFAR spending was used to build the global health infrastructure required to deliver anti-retroviral therapies at scale, this investment was inherent to providing life-saving treatment and also appears to have brought down the costs of doing so over time (Over 2011). Overhead expenditures may be well justified if they contribute to effective delivery of programming.

From 2016 to 2021, we worked with USAID on a pair of randomised controlled trials designed to ask whether economic assistance programmes were delivering good value relative to a ‘benchmark’ of low-overhead cash transfers delivered by the non-profit GiveDirectly and paid for by Google.org. When comparing cash and in-kind programmes at the same cost per beneficiary, we found cash to deliver greater impacts on several programme objectives in spite of the flexibility it offers beneficiaries to spend resources in accordance with their own preferences. Nonetheless, the willingness of USAID to fund the larger group of cash benchmarking studies represented an admirable openness to learning about, and adapting to, evidence on differential cost effectiveness (see the CEGA Cash Benchmarking Initiative).

Designing a cost-equivalent benchmark to study in-kind programmes

Our evaluation of the Gikuriro programme in Rwanda (McIntosh and Zeitlin 2024) illustrates this approach. Gikuriro, meaning ‘well-growing child’ in Kinyarwanda, was an integrated nutrition and WASH programme aimed at promoting better nutrition and health in communities through a variety of behaviour change activities, including village nutrition schools, community health clubs, growth monitoring and promotion by trained community health workers, nutrition and WASH trainings, farmer field schools, distribution of seeds and livestock, local savings groups, and access to improved latrines and hand-washing facilities. This relatively complex and multi-faceted programme was typical of USAID investments to combat child malnutrition in many parts of Africa.

To provide a benchmark for the impacts of Gikuriro relative to a cash-transfer programme with the same delivery costs, we randomly assigned 248 villages to one of three study arms: 74 to Gikuriro, 74 to control, and 100 to cash. In the cash arm, we randomly assigned villages to three smaller treatment amounts intended to bracket the cost of Gikuriro ($66, $111, or $145), as well as a large arm intended to optimise the cost effectiveness of cash ($567). Both programmes were administered to households with at least one child under five who was malnourished, and to poor households with children or pregnant or nursing mothers.

How the programmes compared

After one year, neither Gikuriro nor the cost-equivalent cash transfer had an impact on any of the primary outcomes (child growth, household dietary diversity, maternal or child anaemia, household consumption, or wealth). Gikuriro did have a positive impact on savings among eligible households (a secondary outcome) and cost-equivalent cash had a positive impact on productive assets and consumption assets. The much larger cash transfer led to improvements in consumption, dietary diversity, height-for-age, child mortality, savings, assets and house values, suggesting that larger ‘doses’ of support may have disproportionate impacts.

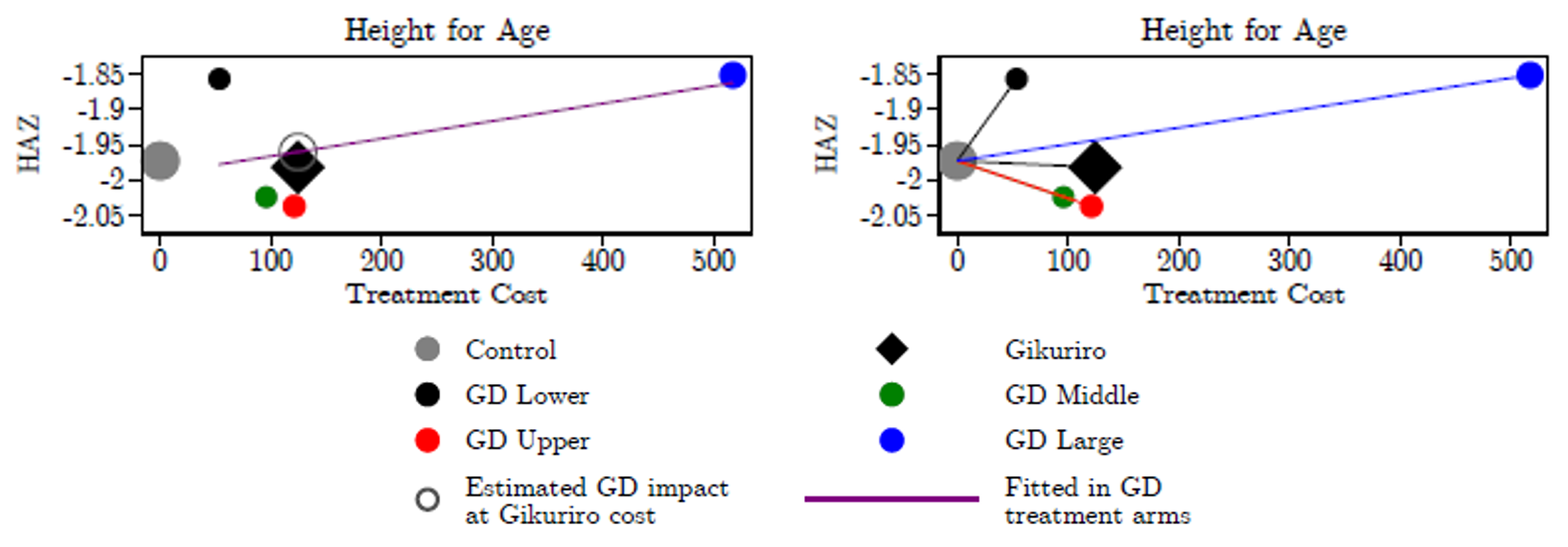

The randomisation of cash transfer values around projected programmatic costs from USAID's perspective allows us to compare impacts between the two modalities at exactly the same regression-adjusted cost. We illustrate this with the figure below, which contrasts cost effectiveness estimates (on the right) with cost-equivalent comparisons (on the left) for the height-for-age z-score (HAZ) outcome. A traditional cost-effectiveness comparison looks at the ratio of benefits created to dollars spent, represented by the slope of the line in the figure on the right. In this instance, the smallest of the cash transfers provides the largest HAZ impact. On the other hand, a donor committed to a given level of expenditure per beneficiary but unsure of the modality that delivers it best would compare Gikuriro's impacts with the regression-fitted estimate of GiveDirectly's cash transfer effects at the Gikuriro-equivalent cost, as illustrated by the hollow circle in the figure at left. Here, we see that cash transfers only marginally (and statistically insignificantly) surpass the benefits of Gikuriro at this level.

Figure 1. Comparing cost-equivalent impacts with cost-effectiveness comparisons

For the full set of outcomes, our cost-equivalent comparisons show significant differences in the use of savings and borrowing; individuals in the cash group paid down debt, while the nutrition and WASH programme induced households to save more (a focus of the savings groups). The cost-equivalent cash was significantly more effective at driving the stock of consumption and productive assets. The large cash arm makes clear a point the cost-equivalent comparison cannot, which is the benefit of increasing the absolute scale of support.

Our second USAID benchmarking study (McIntosh and Zeitlin 2022) was similar in design but compared cash grants to a youth workforce training and entrepreneurship programme. In that case, the cost of the USAID programme was substantially higher; $388 versus $142 in the case of Gikuriro. Using an individually randomised study, the training programme was found to be effective at driving some core outcomes, leading to an increase in working hours and productive assets (primary outcomes), as well as subjective well-being, savings, and business knowledge (secondary outcomes). Nonetheless, we found cash to have a significantly larger cost-equivalent effect than the training programme on productive hours, monthly income, productive assets, and household consumption (as well as important secondary outcomes including subjective well-being, savings, and wealth).

Policy implications for development programme design and efficiency

Typical USAID programming was complex, involving multidimensional programmes with multiple sub-implementing agencies at the local level. Programmes like Gikuriro tended to spread resources over a large number of people and sub-programmes, potentially leading to our finding that programmes have few transformative effects on the entire population of households eligible for the core maternal/child health intervention. One takeaway from the results of our benchmarking studies is the benefit of concentrating resources, both in the sense of focusing on programmes that deliver tangible benefits, and also in spending more per beneficiary so as to move the needle for a whole group in a meaningful way. Indeed, PEPFAR’s spend of $880 per year for patients on antiretroviral therapy (Menzies et al. 2011) is another example of the concentration of resources generating very large per-person benefits.

This evidence-based approach to development funding illustrates numerous ways in which relatively lean development organisations can run programmes with substantial effects on economic outcomes. As Americans reconsider overseas development assistance as both a moral obligation and tool for soft power, it is crucial to understand how effective US development aid can be quickly restored with low administrative cost.

References

George W. Bush Presidential Center (2023), “How PEPFAR, the ‘genius plan,’ came together to save 25 million lives.”

Gneezy, U, E A Keenan, and A Gneezy (2014), “Avoiding overhead aversion in charity,” Science, 346(6209): 632–635.

McIntosh, C, and A Zeitlin (2022), “Using household grants to benchmark the cost effectiveness of a USAID workforce readiness program,” Journal of Development Economics, 157: 102875.

McIntosh, C, and A Zeitlin (2024), “Cash versus kind: Benchmarking a child nutrition program against unconditional cash transfers in Rwanda,” The Economic Journal, 134(664): 3360–3389.

McIntosh, C, and A Zeitlin (forthcoming), “Skills and liquidity barriers to youth employment: Medium-term evidence from a cash benchmarking experiment in Rwanda,” Journal of Human Resources.

Menzies, N A, A A Berruti, R Berzon, S Filler, R Ferris, T V Ellerbrock, and J M Blandford (2011), “The cost of providing comprehensive HIV treatment in PEPFAR-supported programs,” AIDS, 25(14): 1753–1760.

Moss, K, and J Kates (2023), “PEPFAR reauthorization 2023: Key issues,” KFF.

Over, M (2011), Achieving an AIDS transition: Preventing infections to sustain treatment, CGD Books.