Every year, hundreds of millions of people around the world search for a job, while millions of firms look for new recruits. Their efforts enable a large number of households to secure a stable stream of income, and support firms in finding talent and skills. Many of these jobseekers live in cities in low and lower-middle-income countries and a large share are young and first time entrants to the labour market. While, until recently, the study of search in labour markets was primarily focused on OECD economies, the last few years have seen the emergence of a rich body of evidence documenting the labour market barriers faced by jobseekers and firms in low and lower-middle income countries, and evaluating the impacts of a wide set of interventions designed to address these barriers. This emerging literature is the focus of this review.

Who is searching for work in poor countries?

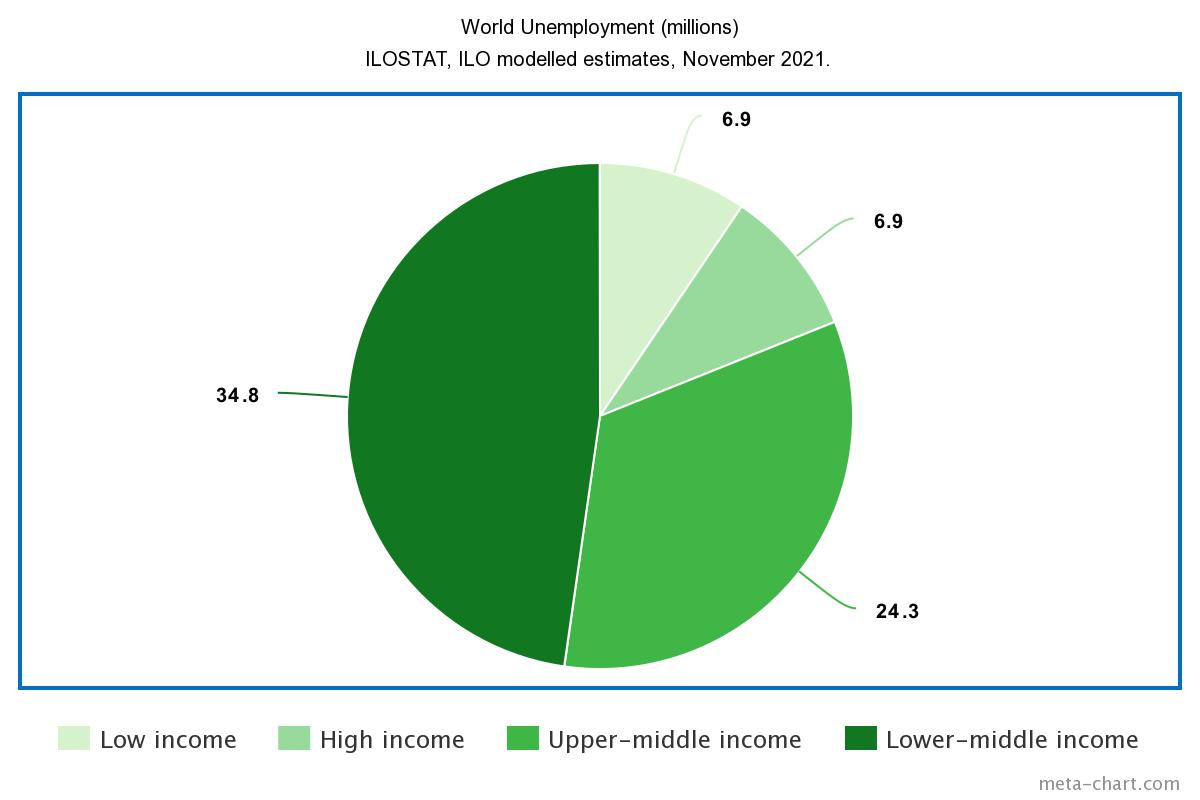

People who search for a job are either unemployed individuals who want to start working, or employed individuals who want to transition to a new employer. A substantial portion of those who search for work are unemployed, and low and lower-middle-income country labour markets are characterised by substantial unemployment rates. Low-income countries have overall unemployment rates above the world average (see Table 1).[1] Unemployment rates in these countries are higher among young people than among the general population. Indeed, the bulk of young unemployed people globally live in poor countries. The ILO estimates that there are about 73 million jobseekers worldwide between the age of 15 and 24. Among these, 41.7 million (57%) live in a low or lower-middle-income country (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: World youth unemployment (in millions).

Table 1: Unemployment and youth unemployment by world and by country income group, 2022.

| Country group | Unemployment rate (percentages) | Youth Unemployment rate | Youth Unemployment (millions) |

| World | 5.3 | 14.9 | 73.0 |

| Low income | 5.7 | 9.8 | 6.9 |

| Lower-middle income | 5.1 | 17.0 | 34.8 |

| Upper-middle income | 5.7 | 16.1 | 24.3 |

| High income | 4.6 | 11.0 | 6.9 |

Sources: ILOSTAT, ILO modelled estimates, November 2021.

The employed in poor countries also often search for a new job while working. On-the-job search is poorly captured in labour market surveys, in part because many surveys only collect questions on search for the unemployed. But job instability is high by international standards. Donovan et al. (2023) collect comparable labour market flows data for a sample of 49 countries ranging from 5,000 to 50,000 USD per capita. They find that the poorer half of the countries in this range have exit rates from employment, job-to-job transitions, and job finding rates that are about twice as high as those of richer countries.[2] The occupation-switching rate is four times as high. This suggests many workers are in highly temporary, insecure jobs of short duration and are thus also searching. Studies of active young jobseekers find high rates of on-the-job search (Abebe et al. 2021a, Carranza et al. 2022).

What do search barriers consist of?

In a typical labour market, jobseekers and firms spend considerable effort searching for one another: jobseekers look for job openings with desirable characteristics, while firms look for recruits with the required skills and abilities. When a good match between a jobseeker and a firm is realised, a job is formed. This process is, however, both costly and risky. Search costs are monetary, psychological and related to the opportunity cost of time. Further, search is risky both because of the stochastic nature of the matching process — one cannot be sure ex-ante as to the time it would take to find a good match — and because both firms and jobseekers often have limited information on market fundamentals as well as on the characteristics of the parties they encounter during the search process (e.g. the true level of skills of a worker, or the true level of amenities of a job). Search costs and limited information can thus make it harder for jobseekers and firms to find the right match. This can decrease the efficiency with which talent is allocated to jobs in the economy.

Five stylised facts about the labour markets of low and lower-middle-income countries are consistent with the existence of meaningful barriers to search.

- As we describe above, these labour markets are characterised both by high levels of search, and high rates of exit from employment (into either unemployment or inactivity). Job search spells can also be quite long (e.g. mean unemployment duration in the 2013 Ethiopian Labour Force survey is 9 months). In other words, it takes a long time for workers to find a job that is a good match between their preferences and those of the employer. Consistent with this, in low-income countries wages tend to increase more slowly as people age compared to richer economies, but they increase faster once people find a good match (Lagakos et al. 2018, Donovan et al. 2023).

- As we explain in detail in the next section, existing surveys suggest that the cost of job search is substantial for the typical active jobseeker. In studies from Ethiopia, Jordan, South Africa and Uganda, job search expenses among active jobseekers amount to at least 16% of total jobseeker expenditure or at least 18% of earnings.

- Employers often report that a lack of skilled workers or the difficulty of identifying a good hire are a constraint to firm growth. The World Bank reports that about 23% of firms cite workforce skills as a significant constraint to their operations. In some African and Latin American countries, this share rises to 40–60% (World Bank 2023).[3]

- Employers regularly hire through social networks. In a recent cross-country survey, 50% of workers in developing countries report having relied on social networks to find their current job (Sapin et al. 2020). The studies we reviewed report similar descriptive findings.[4]

- Online platforms designed to facilitate search are becoming increasingly popular, but their use is far from universal, and can give rise to new search barriers specific to online marketplaces (Fernando et al. 2023, Wheeler et al. 2022).

Overall, these facts are consistent with the presence of search barriers that lengthen search times and worsen the allocation of workers to firms, generating job instability. However, they can also be rationalised by different theories of the labour market, for example by theories that emphasise a mismatch between the skills offered by jobseekers and those demanded by firms. We review the body of work that mainly uses randomised control trials to identify search barriers in specific settings to rigorously establish the presence of search barriers and to quantify their importance.

An important question that we will consider is whether search barriers differ by gender. At least among youth, unemployment rates tend to be similar across genders (e.g. see Table 2 below). However, this masks the fact that a much larger share of women are inactive (neither working nor searching for work) compared to men.[5] Differential search barriers could be a reason for these higher rates of inactivity.

Table 2: Youth unemployment and unemployment rates by sex, world and by country income group, 2022.

| Country group | Sex | Youth Unemployment rate (percentages) | Youth (millions) |

| World | Female | 14.5 | 27.4 |

| Male | 15.2 | 45.6 | |

| Low income | Female | 9.6 | 3.1 |

| Male | 10.0 | 3.8 | |

| Lower-middle income | Female | 15.9 | 10.6 |

| Male | 17.5 | 24.3 | |

| Upper-middle income | Female | 17.4 | 10.7 |

| Male | 15.2 | 13.6 | |

| High income | Female | 10.3 | 3.0 |

| Male | 11.6 | 3.9 |

Source: ILOSTAT, ILO modelled estimates, November 2021.

Structure of the review

This review is organised as follows. In the first part of the review, we discuss search barriers among jobseekers. We first introduce information barriers and then discuss barriers related to the monetary and psychological cost of job search. In the second part of the review, we present the evidence on the search barriers faced by firms. In the third part of the review, we discuss whether search barriers differ by gender. Most of the evidence we discuss in this review quantifies impacts at the level of the individual firm or jobseeker. In the final part of the review, we consider the question of spillovers and general equilibrium effects.

In this current version of the review, we cover 80 studies from 23 low- and middle-income countries, published mostly in the last 10 years. Figure 2 below shows the geographical distribution of the evidence we have gathered.

Figure 2: The evidence base from LMICs.

References

Abebe, G, A S Caria, M Fafchamps, P Falco, and S Franklin (2021a), “Anonymity or Distance? Job Search and Labour Market Exclusion in a Growing African City,” Review of Economic Studies, 88: 1279-1310.

Bassi, V, and A Nansamba (2022), "Screening and Signalling Non-Cognitive Skills: Experimental Evidence from Uganda," The Economic Journal, 132(642): 471–511.

Beaman, L, and J Magruder (2012), "Who gets the job referral? Evidence from a social networks experiment," American Economic Review, 102(7): 3574-3593.

Donovan, K, W J Lu, and T Schoellman (2023), “Labor Market Dynamics and Development,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 138(4): 2287–2325.

Fernando, A N, N Singh, and G Tourek (2023), "Hiring frictions and the promise of online job portals: Evidence from India," American Economic Review: Insights.

Ghisletta, A, J Stöterau, and J Kemper (2021), “The Impact of Vocational Training Interventions on Youth Labor Market Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis,” Working Paper.

Groh, M, D McKenzie, N Shammout, and T Vishwanath (2015), “Testing the importance of search frictions and matching through a randomized experiment in Jordan,” Journal of Labor Economics, 4:7.

Lagakos, D, B Moll, T Porzio, N Qian, and T Schoellman (2018), “Life Cycle Wage Growth across Countries,” Journal of Political Economy, 126(2): 797-849.

Sapin, M, D Joye, C Wolf, J Andersen, Y Bian, A Carkoglu, Y Fu, E Kalaycioglu, P V Marsden, and T W Smith (2020), “The ISSP 2017 social networks and social resources module,” International Journal of Sociology, 50(1): 1–25.

Schöer, V, N Rankin, and G Roberts (2014), “Accessing the first job in a slack labour market: Job matching in South Africa,” Journal of International Development, 26: 1-22.

Wheeler, L, R Garlick, E Johnson, P Shaw, and M Gargano (2022), “LinkedIn(to) Job Opportunities: Experimental Evidence from Job Readiness Training,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 14: 101–125.

World Bank (2023), “Skills and Workforce Development,” worldbank.org, 11 October.

Contact VoxDev

If you have questions, feedback, or would like more information about this article, please feel free to reach out to the VoxDev team. We’re here to help with any inquiries and to provide further insights on our research and content.