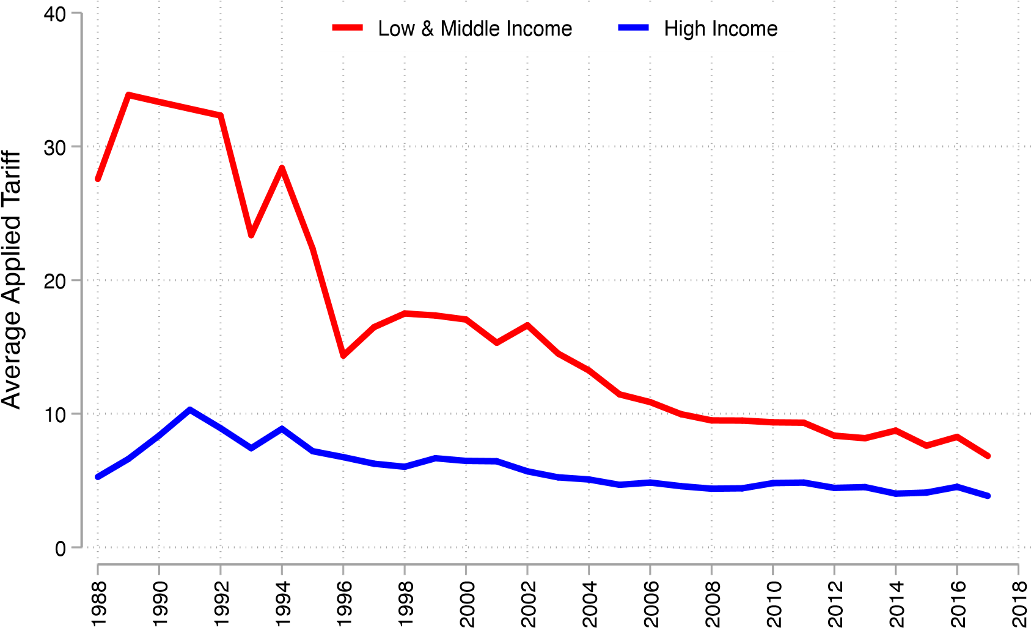

Over the last four decades, many developing countries implemented reforms that lowered barriers to trade. Nevertheless, developing countries remain much less open to global commerce than developed ones. Figure 1 shows that average tariffs remain higher in developing countries compared to high-income countries, while weak contract and regulatory enforcement, inadequate transport infrastructure, search frictions, and other distortions mean that the same pattern likely holds for other trade barriers.

Understanding the impacts of these high trade barriers on developing countries—and policies to reduce them—should be of great interest to both international and development economists. However, the core insights provided by research in international trade have mostly been informed by neoclassical trade models and from empirical patterns of trade from developed countries (e.g. see Costinot and Rodriguez-Clare (2014) for a review article). Applying the lessons from these studies to developing countries requires caution given that standard models typically feature undistorted economies whose structures differ substantially from developing economies characterised by pervasive frictions. Understanding how trade policies interact with frictions such as informality, weak contract enforcement, and credit constraints is vital for policymakers who wish to implement more effective policies.

Figure 1: Average Tariff Rate

Fortunately, in recent years, there has been a resurgence in research that examines how international trade interacts with specific frictions prominent in developing countries. These interactions take many forms: while the effects of a trade reform depend on pre-existing frictions, opening to trade can also exacerbate or mitigate their impact. To make progress, scholars have combined rich sources of data from developing countries with a diversity of empirical methodologies—from randomised trials that induce firms to export to structural models of large trade liberalisation episodes.

This survey provides an up-to-date assessment of the trade and development literature, and will be revised annually. It builds heavily on the structure proposed by Atkin and Khandelwal (2020) that classifies the literature into three broad categories of frictions pervasive in the developing world. The first is weak institutions operating at the country level, with an emphasis on imperfect enforcement of tariffs, contracts, and other regulations. The second is market failures, such as artificially high input and transport costs, which affect most firms in a given market. The third consists of firm-specific distortions, such as political connections and knowledge spillovers, that can give rise to misallocation across firms. While imperfect, this taxonomy reflects the scale at which each friction operates and thus at which evidence must be collected. To limit the scope of this review, we restrict attention to micro-empirical papers that focus on the interaction of distortions with international trade for developing countries. Thus, we exclude important research on firms in developing countries, on links between trade and macroeconomic growth, as well as papers that evaluate neoclassical predictions of trade models such as the trade and inequality literature. For a complementary perspective, we also refer readers to two recent surveys by Atkin and Donaldson (2022) and Verhoogen (2022).[1] The former puts forward a development accounting framework to synthesise the ways distortions impact the gains from trade in developing countries. The latter develops a framework to review the literature on firm-level upgrading in developing countries.

In each section, we highlight work answering three related questions. First, how do existing frictions impact trade flows, both directly and in interaction with trade reforms? Second, does trade change the severity of the friction? Third, what policy interventions are most effective in light of the friction? For many of the institutions, market failures, and firm-level distortions we cover, one or more of these questions remain unanswered. As we emphasise throughout the paper, these gaps provide promising directions for future research.

References

Atkin, D and D Donaldson (2022), “The Role of Trade in Economic Development,” Handbook of International Economics, Elsevier.

Atkin, D and A K Khandelwal (2020), “How Distortions Alter the Impacts of International Trade in Developing Countries,” Annual Review of Economics, 12: 213–238.

Costinot, A and A Rodriguez-Clare (2014), “Chapter 4 - Trade Theory with Numbers: Quantifying the Consequences of Globalization”, in Handbook of International Economics, ed. by G Gopinath, E Helpman and K Rogoff, vol. 4, Elsevier, 197–261.

Krueger, A O (1984), “Trade Policies in Developing Countries,” in Handbook of International Economics, Volume 1, ed. by R. W. Jones and P. B. Kenen, Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Verhoogen, E (2022), “Firm-Level Upgrading in Developing Countries,” Journal of Economic Literature.

Contact VoxDev

If you have questions, feedback, or would like more information about this article, please feel free to reach out to the VoxDev team. We’re here to help with any inquiries and to provide further insights on our research and content.