Mobile money is not mobile banking — it is a distinct product. It is most often provided by telecommunications companies, henceforth telcos (examples of exceptions are B-Cash in Bangladesh and Splash in Sierra Leone[1]). Mobile money systems, therefore, lie outside the formal banking system[2] and have often been referred to as shadow banking systems (for a definition of a shadow banking system, see Bernanke 2012). From the point of view of the consumer or user, the mobile money system is a payment account that sits on their mobile phone. It operates through a menu on their SIM card and allows them to engage in a variety of financial transactions.

In the initial stages of mobile money, the focus was largely on allowing consumers to make person-to- person (P2P) payments digitally without needing a bank account or a wire transfer. As mobile money expanded its purview, consumers were able to use it to pay their bills (including utilities), to store and hold money (i.e. save), to make person-to-business (P2B) payments, to receive payments from businesses (such as wages), and to receive government-to-person (G2P) payments.

Mobile money works very simply. On the consumer side, the consumer registers an account at a mobile money agent, providing information that is equivalent to the Know Your Customer (KYC) banking rules. They register for the service with a government-issued ID (in some countries this is the ID used for voting)[3]. This process takes a few minutes (as opposed to opening a bank account, which could take days or weeks).

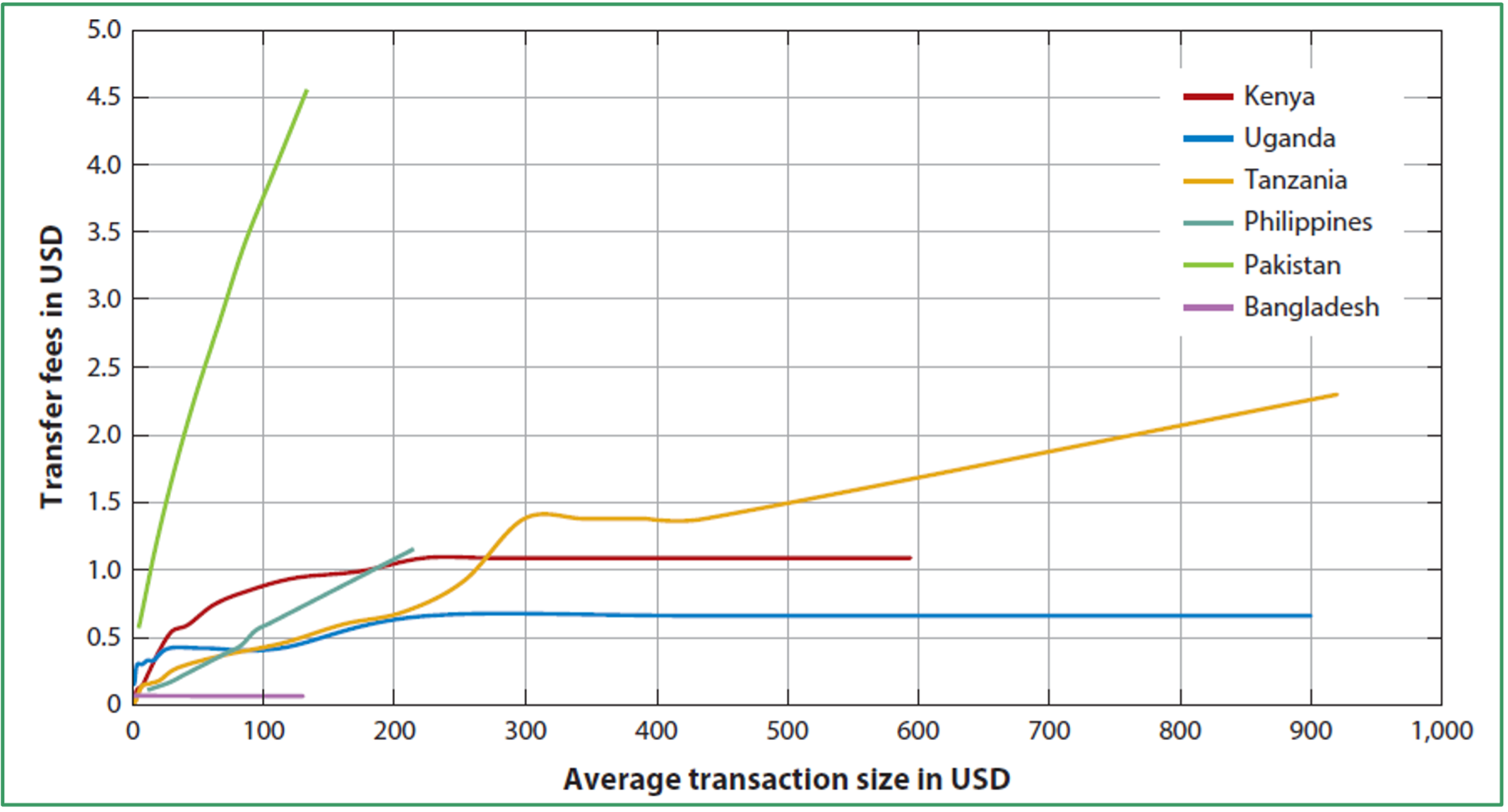

To be able to make any payments from their account, a consumer must deposit cash into it. They do this at any mobile money agent in the country. They give the agent the cash and immediately get a notification that cash has been deposited in their account. From there, they can use the menu on their mobile phone to transfer that money to anyone else in the country with a cell phone via their phone number. To get their cash back, they have to return to the agent. Each of these transactions (depositing is often an exception) incurs transaction fees; of course, the transaction fee schedule varies across countries. Figure 4 shows the transaction fees for transfers across a selection of different countries.[4] The consumer side is, therefore, quite simple – a mobile money account is superficially very similar to a bank account, allowing deposits, withdrawals (a number of banks in the developing world impose withdrawal fees, especially for low-balance accounts), holding money, and making transfers to other individuals. However, there is no interest paid on deposits, and the deposits and withdrawals are done through an agent for the mobile money service and not a bank branch.[5]

In addition, other standard bank services, such as loans or standing order payments, are generally not available through mobile money.[6] Although the consumer side of mobile money feels similar to a bank account, the back end of the system and how it operates are quite different. The money in a mobile money account is called e-money (or electronic money) and always trades one for one with cash (minus the transaction costs for the particular transaction being conducted). When a consumer deposits money in their mobile money account, they are in fact purchasing the equivalent value in e-money from the agent. This means that the agent must hold a stock of e-money that they can then trade with the consumer. Similarly, if the consumer wants to withdraw money from their mobile money account, they are selling e-money to the agent for cash of the equivalent value (minus the transaction cost).

Figure 4: Transaction fees for Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, the Philippines, Pakistan, and Bangladesh

The agent’s primary role is, therefore, to manage their float or inventory of e-money as they would their inventory of any other commodity they stock. Most of these agents are either existing businesses that sell airtime and phones, or small retailers such as basic grocery stores, petrol stations, chemists, or tailors. As of December 2019, the number of agent outlets tripled over the preceding five years to 7.7 million (GSMA 2019). Agents always have an existing business and provide mobile money services as an addition to their regular business. The requirements to become an agent vary across countries. In Kenya, for example, potential agents need to apply to the mobile money operator to become an agent (see Jack et al. 2010 for more details on the evolution of the agent system in Kenya).

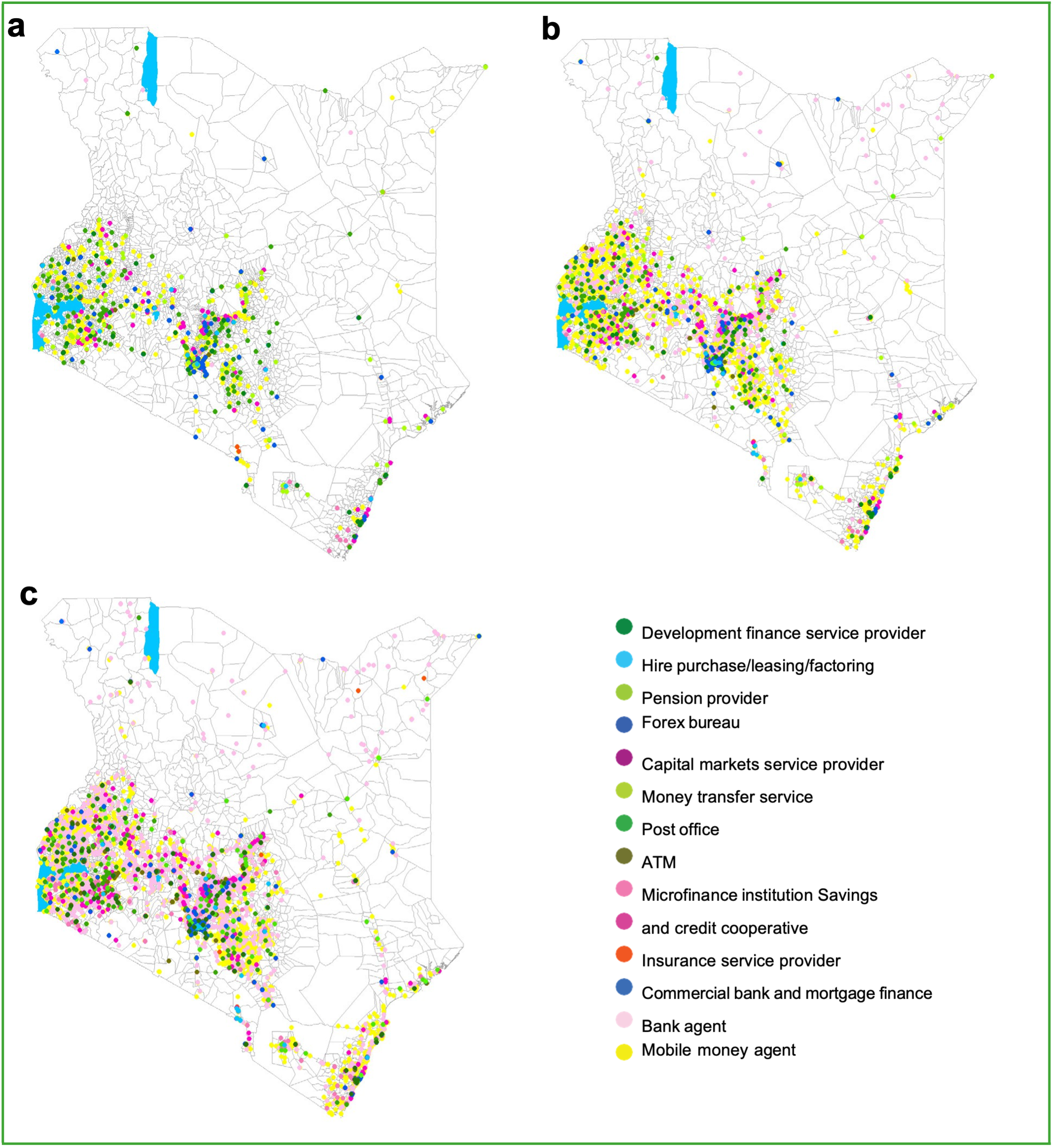

Figure 5: Agent density in Kenya in (a) 2007, (b) 2011, (c) 2015

Applicants have to have a bank account and an Internet connection to be considered, and, if they are approved as agents, they have to purchase an initial quantity of e-money valued at $1,000.[7] They can then trade this e-money as they would any other commodity of which they hold inventories. If they run out of e-money, they go back to the operator to purchase more, and if they run out of cash, they can sell e-money back to the operator. Since 2009, banks have been allowed to be agents to the agents, so that agents can trade cash and e-money back and forth with bank branches rather than only with the operator. Agents are a core part of the mobile money model, as they provide consumer cash-in and cash-out services, i.e. they serve as the ATM equivalents. Therefore, the extent of the network of these agents is crucial.

Figure 5 shows the initial distribution of M-PESA (the only mobile money service at the time) agents in Kenya in 2007, when the service was launched, as well as the subsequent agent expansion through 2015.

Aside from consumers and agents, there is a third component underlying the operation of mobile money: what happens to the money itself. The cash deposited in mobile money accounts is usually ultimately held in trust accounts, which are administered by a small number of commercial banks in the country. The trust accounts are owned by the mobile money account holders – think of each mobile money account holder as having rights over a small sliver of one of these trust accounts. However, the account holder cannot deposit or withdraw money from their mobile money account at the commercial bank that holds a trust account (unless the bank branches are themselves agents). The account holder can only deposit and withdraw money from a mobile money agent. Similarly, an individual’s mobile money account is not considered to be a bank account – it does not earn interest and loans are not available to users.[8] However, the trust accounts often earn interest, as they are accounts in the commercial banking system. Given this structure, the mobile operator with which the mobile money account is held is itself not subject to the same regulations under which commercial banks or other deposit-taking institutions conduct business.[9]

Regulation of mobile money

On the regulatory side, mobile money has required some innovation to build the necessary governance and institutions. For example, in the case of Kenya, when M-PESA started growing, a number of the commercial banks lobbied the Central Bank of Kenya to restrict and regulate it more heavily. These efforts were largely unsuccessful, as an audit by the Central Bank revealed few issues and user satisfaction surveys were extremely positive. However, this was soon followed by the Central Bank implementing agent banking regulations in 2010, which allowed banks and other financial institutions to offer some banking services (account opening, deposits, and withdrawals) at nonbank agents, the same agents targeted by M-PESA. Banking institutions, previously limited to expensive brick-and-mortar operations, were therefore allowed to compete more directly with mobile money.

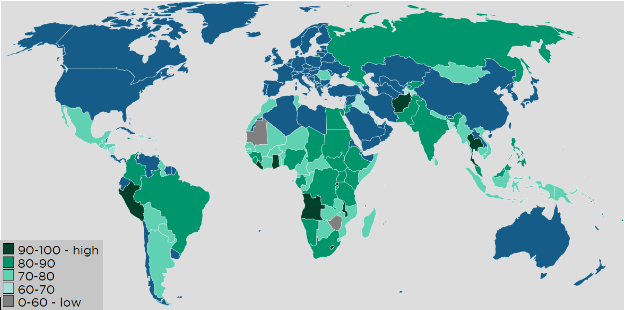

Aron (2017) provides an excellent review of the regulatory side of mobile money systems, including how the regulation for mobile money may need to be unbundled at the level of the component systems and how regulation should be built around each of the components (such as customer registration, exchange and storage of e-money, foreign transfers, and interoperability). The GSM Association (GSMA) Mobile Money Regulatory Index (2021) conducts a quantitative assessment of the extent to which regulations have been effective in enabling mobile money adoption (GSMA 2021), see Figure 5. The index scores each economy across six different dimensions, using 26 different weighted indicators, and an overall index is computed for each economy by using these dimensions. The dimensions include: authorisation; consumer protection; transaction limits; KYC requirements; agent networks; and investment and infrastructure environment. Scores range from 0-100, with a higher score associated with more enabling regulation. In 2021, GSMA Mobile Money Regulatory Index in Sub-Saharan Africa ranges from 42 in Mauritania to 98 in Ghana, with an average score of 83.

Figure 6: Mobile money regulatory index worldwide

In this section, we touch on only the main innovations in the regulatory system that have emerged from the advent of mobile money. Most countries have created their own regulatory frameworks around mobile money, but there are many common elements. The first is the requirement to report on aggregate transactions (and sometimes high-value individual transactions) to the regulator in charge—this is often the Central Bank but may also include the Communications Commission. Often, there are limits on transaction sizes, and the amount that can be held in a mobile money account; for example, in Kenya, these limits are $700 and $1,000 respectively, and in Uganda, $1,500 and $1,200, respectively. Similarly, there is often direct regulation around the trust or bank accounts that hold the float, and rules on whether these can earn interest (as in Kenya, Malawi, Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, and several Pacific Island countries; see Greenacre & Buckley 2014) or must be 100% cash reserve accounts deposited at the Central Bank (as in the Philippines). When these accounts earn interest, rules regulate whether interest is to be disbursed to consumers and, if not, what happens to it. In Kenya, for example, the interest from the trust account has to go to charity; in Tanzania and Liberia, it can be disbursed back to consumers; and in India, the providers would pay out the interest earned on the value stored in the mobile account through payment banks (see below). Although there are variations in the exact regulatory framework across countries, these regulations are far less stringent than those for commercial banks.

A final regulatory issue that has been debated heavily in the policy sphere (see Camner 2013, Davidson and Leishman 2016) is the issue of interoperability, the ability to transact with mobile money across service providers. Interoperability can be at the platform level or the agent level (allowing customers or agents of different services to send mobile money to each other, respectively), or at the customer level (allowing customers to access their mobile money account through any SIM) (Davidson and Leishman 2016). As mobile money systems come closer and closer to becoming payment systems, the issue of whether transactions can cross different telcos has become relevant. In some countries, like Bangladesh and Sierra Leone, this is not an issue because, in both countries, at least one mobile money operator is an entrepreneur independent of a telco but with agreements with a number of different telcos. However, in most countries where a given product is launched by a single telco, policy makers are debating their role in requiring interoperability, given how important network externalities are in this industry. To date, Tanzania is the only country where this is operational. It was enabled by the industry leading the discussions and adopting common business standards to ease switching, working closely with the Bank of Tanzania, which oversaw the regulatory process. Afghanistan has a “switch” that would allow interoperability, however, no telcos have signed up to use it as the subscription fees are too high.

A different approach to regulation that is worth mentioning is that of India. Starting in 2014, the Reserve Bank of India issued licences to several entities to function as payments banks, which remain separate from commercial banks with separate regulated functions. Unlike a regular small bank, this new financial institution is not permitted to extend credit. However, it can perform all the other functions of a banking institution, such as taking deposits, paying interest, enabling transfer and remittances, issuing debit and ATM cards, and offering Forex services. The aim of setting up these payments banks was to boost financial inclusion across the country and enhance the use of mobile services in banking. Some of the first payments bank licences in India were awarded to Aditya Birla Nuvo, Reliance Industries, Sun Pharmaceuticals, National Securities Depository, Vijay Shekhar Sharma (Paytm), Fino PayTech, Airtel M Commerce Services, Vodafone M-PESA, the Department of Posts, Cholamandalam Distribution Services, Dilip Sanghvi, and Tech Mahindra (the last three have since surrendered their licences). In late 2016, the Indian economy was demonetized and the two largest notes withdrawn from circulation. Although much chaos ensued (for early opinions on demonetization, see Banerjee 2016, Basu 2016), payments banks and digital payment services like Paytm have made immense gains in the months post-demonetization, as individuals switch from cash to digital payments where it is easy to do so (Chakravorti 2017). Demonetisation may prove to be the biggest push yet for digital payments in India.

References

Aron, J (2017), “’Leapfrogging’: A survey of the nature and economic implications of mobile money” (No. 2017-02), Centre for the Study of African Economies, University of Oxford.

Banerjee, A (2016), “Bad economics can bite back”, The Hindustan Times.

Basu, K (2016), “In India, black money makes for bad policy”, The New York Times.

Bernanke, B S (2012), “Some reflections on the crisis and the policy response”, Rethinking Finance: Perspectives on the Crisis conference.

Camner, G (2013), “Snapshot: implementing mobile money interoperability in Indonesia”, Mobile money for the unbanked case studies: Insights, best practices and lessons from across the globe, 11-19.

Chakravorti, B (2017), “Early lessons from India’s demonetization experiment”, Harvard Business Review, 14.

Davidson, N and P Leishman (2012), “The case for interoperability. Assessing value that interconnection for mobile money services would create for customer and operators”, GSMA report.

Davidson, N and P Leishman (2016), “The case for interoperability. Assessing value that interconnection for mobile money services would create for customer and operators”, GSMA report.

GSMA (Groupe Spec. Mob. Assoc.) (2019), “State of the industry: Report on mobile financial services for the unbanked,” Groupe Spec. Mob. Assoc., London.

GSMA (Groupe Spec. Mob. Assoc.) (2021), “Mobile Money Regulation Index”, Groupe Spec. Mob. Assoc., London.

Greenacre, J and R P Buckley (2014), “Using trusts to protect mobile money customers”, Sing. J. Legal Stud., 59.

Jack, W, T Suri and R M Townsend (2010), “Monetary theory and electronic money: Reflections on the Kenyan experience”, FRB Richmond Economic Quarterly, 96(1), 83-122.

Suri T (2017), “Mobile Money”, Annual Review of Economics, 9:1, 497-520

Contact VoxDev

If you have questions, feedback, or would like more information about this article, please feel free to reach out to the VoxDev team. We’re here to help with any inquiries and to provide further insights on our research and content.