The mobile phone has been amongst the most rapidly adopted innovations in the world, with SIM cards and airtime (prepaid phone minutes)[1] now ubiquitous in many economies. This is particularly true in developing economies: as of 2021, there were 1.15 billion and 806.1 million subscribers in India and Sub- Saharan Africa respectively (International Telecommunication Union (ITU) World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators Database). A large body of literature shows the benefits of mobile phones (see Aker and Mbiti 2010 for a review), with specific studies showing that communication via text can affect credit repayment (e.g. Karlan et al. 2012), savings behaviours (Karlan et al. 2016), adherence to medicinal treatments (for one example among many, see Lester et al. 2010), and voting behaviour (e.g. Marx et al. 2016). The expansion of mobile phone markets and networks has been accompanied by innovations that add substantial value for, and provide beneficial services to, customers – in particular, financial services that were previously inhibited by poor infrastructure and high transaction costs.

Figure 1: Mobile money adoption across the world (Source: Global Findex)

This review focuses on one of the most widespread technological innovations in the context of developing economies: mobile money. The most prominent and best-known innovation adding service over the mobile phone has been mobile money—which, in 2021, processed over a trillion dollars, or $2.7 billion a day, a 31% year-on-year increase (GSMA 2022a). Mobile money enables mobile phone owners to deposit, transfer, and withdraw funds without owning a bank account. It is therefore distinct from mobile banking, which allows access to one’s existing bank account via a mobile phone. Mobile money is an app in the true sense of the word because it operates via software that is installed on a SIM card, although it is typically run on regular phones rather than smartphones. Mobile money is especially important in developing economies, and is available in 96% of the countries where less than a third of the population have an account at a formal financial institution (GSMA 2019).

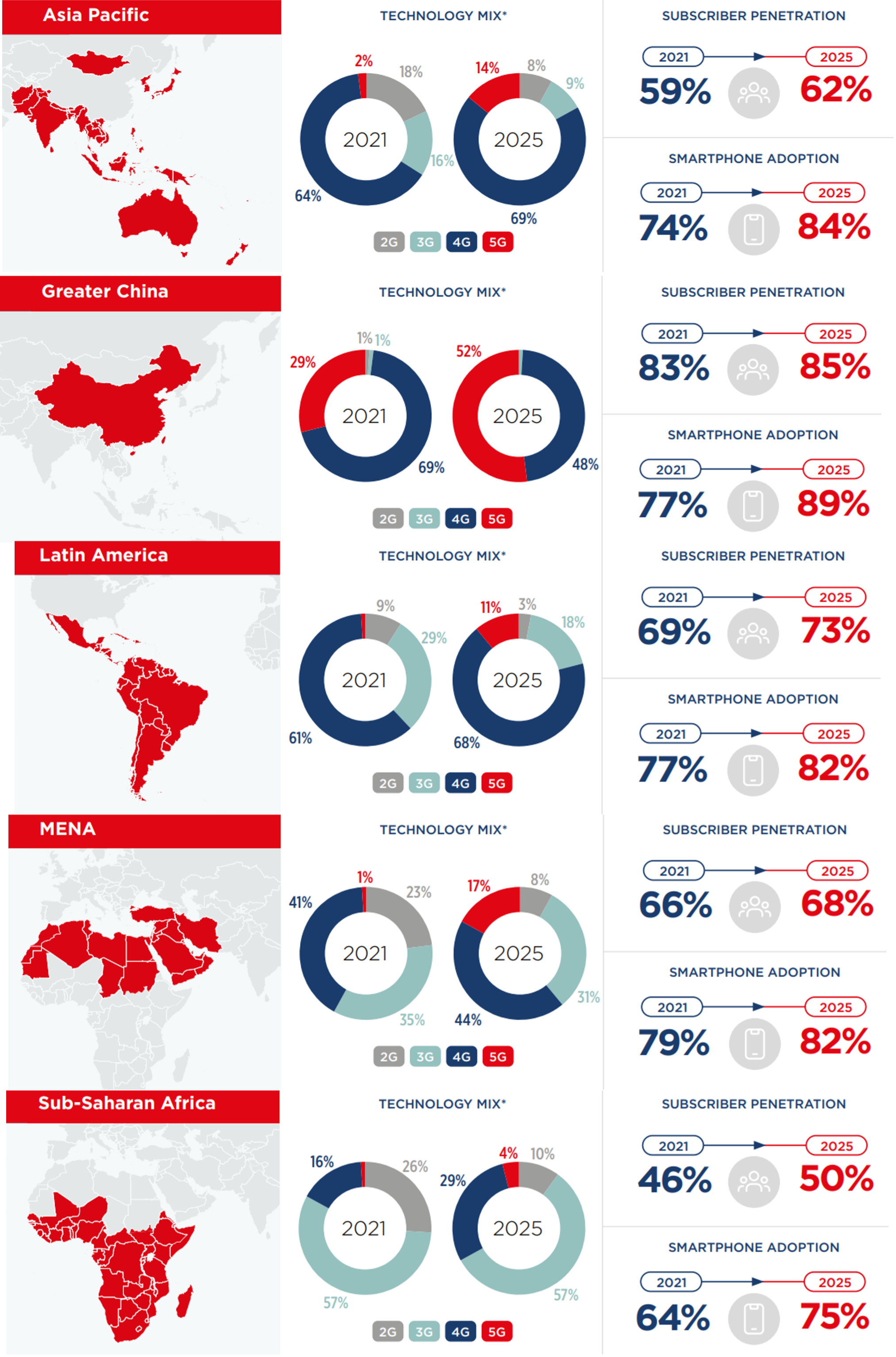

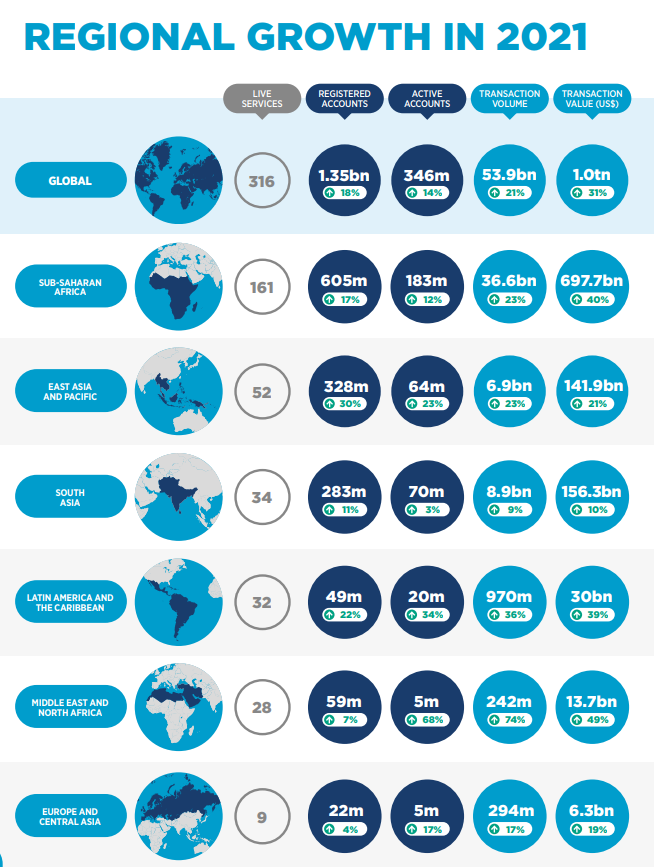

Mobile money has been adopted widely and quickly across the developing world. Figure 1 shows mobile money adoption across the world, while Figure 2 shows the adoption of mobile phones worldwide in 2021 and projections for adoption 2025, and Figure 3 the adoption of mobile money as of 2021.

Figure 2: Mobile phone penetration

Early deployments of mobile money systems started in the mid-2000s, with the Philippines, Kenya, and Tanzania being among the first countries to use the service. Since then, this innovation has spread quickly across the developing world. By the end of 2021, there were a total of 316 mobile money services being offered in 98 countries; there were more than 1.35 billion registered mobile money accounts globally, including 518 million actively used for a transaction in the previous 90 days (GSMA 2022a). Though nearly half of all accounts are registered in Sub-Saharan Africa (605 million), in 2021 there were also over half a billion registered accounts in Asia (GSMA 2022a). The most successful and well-known mobile money product was launched in 2007 in Kenya by one of the main telecommunications companies in the country, Safaricom. The product is called M-PESA, M referring to mobile and pesa being the word for money in Swahili. M-PESA has reached almost universal coverage in Kenya.

Figure 3: Mobile payment account penetration, 2021

The aim of this VoxDevLit is not to provide a comprehensive review of all aspects of mobile money,[2] but rather to highlight the economics behind the product: what may have driven its adoption and what are its impacts. Given the success of M-PESA, much of the research discussed in this review focuses on Kenya, although there are some more recent studies of mobile money systems in other countries that are now catching up, as well as studies that focus on specific interventions that promote the use of mobile money in a specific context. Towards the end of the review, we also discuss the more recent innovations that build on mobile money systems to deliver additional financial services and value. Although these innovations exist, they have not given rise to a thriving fintech[3] sector. Therefore, we also discuss constraints to their growth, what this implies for the future of mobile money in developing economies, and where the most exciting opportunities for research may be.

The rest of this review is structured as follows. Section 3 describes how mobile money works in practice, and provides a brief description of the regulatory innovations that have accompanied its expansion. Section 4 discusses the adoption of mobile money, and outlines the business models that have typically contributed to its success (or lack thereof). Section 5, covers the impacts of mobile money, especially on financial resilience, and how the product’s capacity to reduce transaction costs for internal remittances has contributed to these impacts. In Section 6, we describe the few innovations that have followed the initial expansion of mobile money, with a focus on East Africa, where adoption is almost universal. This section also discusses why few services have successfully built on mobile money – a phenomenon that highlights how mobile money systems remain very far from being true payment systems. Finally, we speculate on what may be needed to unleash further financial innovation.

References

Aker, J C and I M Mbiti (2010), “Mobile phones and economic development in Africa”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 24(3), 207-32.

Aron, J (2017), “’Leapfrogging’: A survey of the nature and economic implications of mobile money” (No. 2017-02), Centre for the Study of African Economies, University of Oxford.

Davidson, N and P Leishman (2012), “The case for interoperability. Assessing value that interconnection for mobile money services would create for customer and operators”, GSMA report.

GSMA (Groupe Spec. Mob. Assoc.) (2019), “State of the industry: Report on mobile financial services for the unbanked,” Groupe Spec. Mob. Assoc., London.

GSMA (Groupe Spec. Mob. Assoc.) (2022a), “State of the Industry Report on Mobile Money 2022”, Groupe Spec. Mob. Assoc., London.

GSMA (Groupe Spec. Mob. Assoc.) (2022b), “The Mobile Economy 2022”, Groupe Spec. Mob. Assoc., London.

International Telecommunication Union (ITU), “World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators Database”, Available at http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.CEL.SETS?year_high_desc=true

Karlan, D, M Morten and J Zinman (2012), “A personal touch: Text messaging for loan repayment” (No. w17952), National Bureau of Economic Research.

Karlan, D, M McConnell, S Mullainathan and J Zinman (2016), “Getting to the top of mind: How reminders increase saving”, Management Science, 62(12), 3393-3411.

Lester, R T, P Ritvo, E J Mills, A Kariri, S Karanja, M H Chung... and F A Plummer (2010), “Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTel Kenya1): a randomised trial”, The Lancet, 376(9755), 1838-1845.

Marx, B, V Pons and T Suri (2016), “Voter mobilization can backfire: Evidence from Kenya”, Unpublished paper.

Contact VoxDev

If you have questions, feedback, or would like more information about this article, please feel free to reach out to the VoxDev team. We’re here to help with any inquiries and to provide further insights on our research and content.