From 1922 to 1923, over 1.2 million Greek Orthodox migrated from Anatolia to Greece, raising its population by 20%. How did the human capital decisions of refugees differ from natives, and how do they continue to impact the Greek economy today?

Editor’s note: For a broader synthesis of themes covered in this article, check out our VoxDevLit on Refugees and Other Forcibly Displaced Populations. This article also appeared on VoxEU.

About a century ago, the international community, represented by the newly established League of Nations, experienced one of its first humanitarian crises as millions of predominantly Christian Armenians, Greeks, and Assyrians, facing persecution and ethnic cleansing, fled the disintegrating Ottoman Empire. Following a unique-at-the-time Convention for a Forced Population Exchange, from 1922 to 23, about 1.2 to 1.5 million Greek Orthodox abandoned their ancestral homelands in Anatolia and settled in Greece, raising its population by 20% (Murard 2023). At the same time, more than 400,000 Muslims followed the reverse route from Macedonia and Crete to Turkey. Refugees who had lost children, family, and land arrived penniless, sick, and hopeless in Greece under the chaotic conditions that followed the burning of Smyrna and the atrocities in Pontus (Black Sea).

The Asia Minor (or Great) Catastrophe has profoundly shaped modern Greece, leaving a lasting imprint on its society, literature, and, art. Against a plethora of narratives and novels, which have preserved memory and shaped identity, in recent work (Michalopoulos et al. 2025), we quantify the dynamic impact of displacement on human capital, a core feature of immigrants’ remarkable integration in modern Greece.

Mapping refugee flows and settlements in contemporary Greece

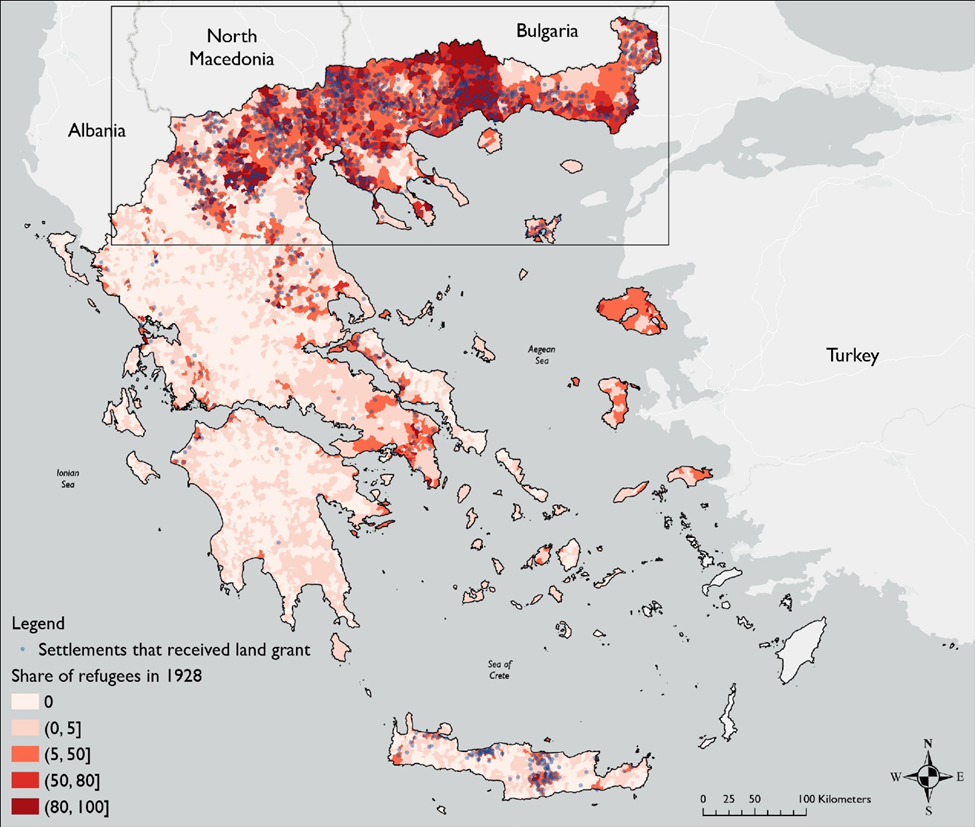

The starting point of our research involved compiling a comprehensive, granular map of all refugee and autochthonous hamlets, small and large villages, towns, and cities in Greece. Through analysing and georeferencing the 1928 General Population Census, the only one that inquired about refugee status, we provide, for the very first time, a complete mapping of the 1.2 million refugees’ presence across thousands of settlements (11,003 settlements across 5,605 communities (koinotites)). About half settled in Greece’s three main cities—Athens, Thessaloniki, and Piraeus—and eighty other urban hubs, and the other half settled in the countryside, where they received resources and assistance to start their new lives. Figure 1 shows that most refugees in the Greek countryside settled in Macedonia and Thrace, where the majority of the 416,000 departing Muslims resided. In 1928, almost half (45%) of Macedonia’s and one-third of West Thrace’s population comprised refugees. However, as shown in Figure 1, Panels (b) and (c), there is considerable variation within Macedonia and its provinces (eparchies).

Figure 1: Refugees in 1928 and land grants across settlements

(a) Greece

(b) Macedonia and West Greece

(c) Giannitsa province

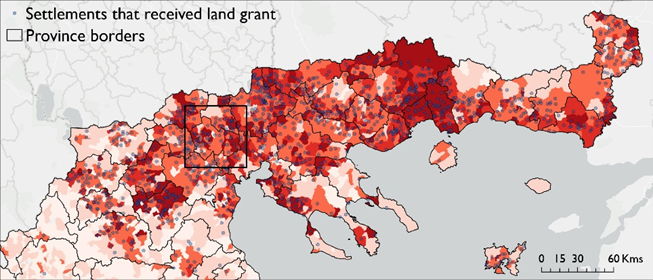

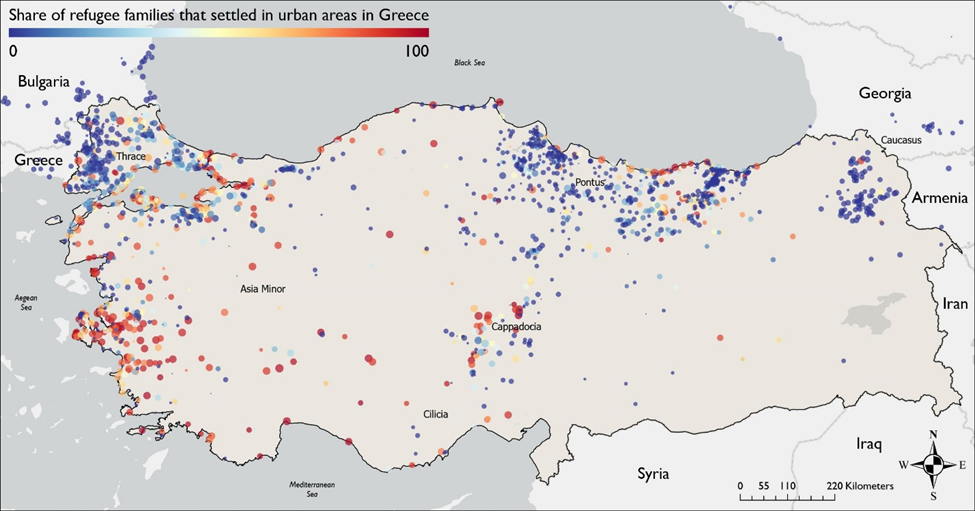

We also digitised and analysed the catalogues compiled by the Greek Refugee Settlement Commission (RSC), the independent and monitored by the League of Nations agency tasked with the colossal task of their integration; the individual catalogues record not only the settlement but also the exact origin of rural and urban refugees (household heads) in Anatolia. We can thus map, for the very first time, (almost) all Greek Orthodox communities in contemporary Turkey, as well as in Ukraine, Bulgaria, Romania, Russia, and the broader Caucasus region. Figure 2 maps the origin settlements of refugees living in Greece in the mid-1920s.

Figure 2: Settlements of Greek-Orthodox refugees in Anatolia

Given the strong refugee lineage in contemporary Greece, these mappings not only allow addressing many fascinating questions about the impact of refugees on the Greek economy, society, and polity but also facilitate a deeper understanding of modern Greek society. We have thus created Anatolia Imprints, a portal where visitors can search their ancestry origin and settlement in Greece and interactively visualise the data.

The impact of uprootedness on human capital accumulation among refugees

A widespread conjecture suggests that displaced individuals and members of ethnic and religious minorities facing repression invest in portable human capital rather than land or physical assets, which can be easily expropriated. The so-called uprootedness hypothesis is prominently featured in Jewish history, although the evidence is inconclusive, as the Jews' transition to human capital and skill-intensive professions occurred during a relatively peaceful period (Botticini and Eckstein 2012). Likewise, the few empirical studies on significant forced displacement episodes yield inconclusive evidence.

For instance, the innovative research of Becker et al. (2020) on displacement after the ‘redrawing’ of Poland’s border following World War II shows that the offspring of Polish migrants from eastern regions (annexed by the Soviet Union), who moved to the western former Germanic areas have significantly higher educational outcomes and value human capital more. On the other hand, multiple studies on the educational investments of German expellees from Eastern Europe to West Germany after WWII fail to detect ‘uprootedness human capital effects’, despite a sizable move of migrants from agriculture to manufacturing and services (Bauer et al. 2013) and strong urbanisation effects (Ciccone and Nimczik 2023, Peters 2022); see Becker and Ferrara (2020) for an overview of research on forced displacement.

Similarly, the creative work of Sarvimäki et al. (2022) studies the outcomes of forcibly displaced people from Finland’s eastern regions (also annexed by the Soviet Union during WWII), documenting significant but heterogeneous effects on human capital, which stem from refugees’ moving from agriculture to manufacturing and services.

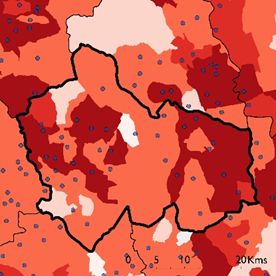

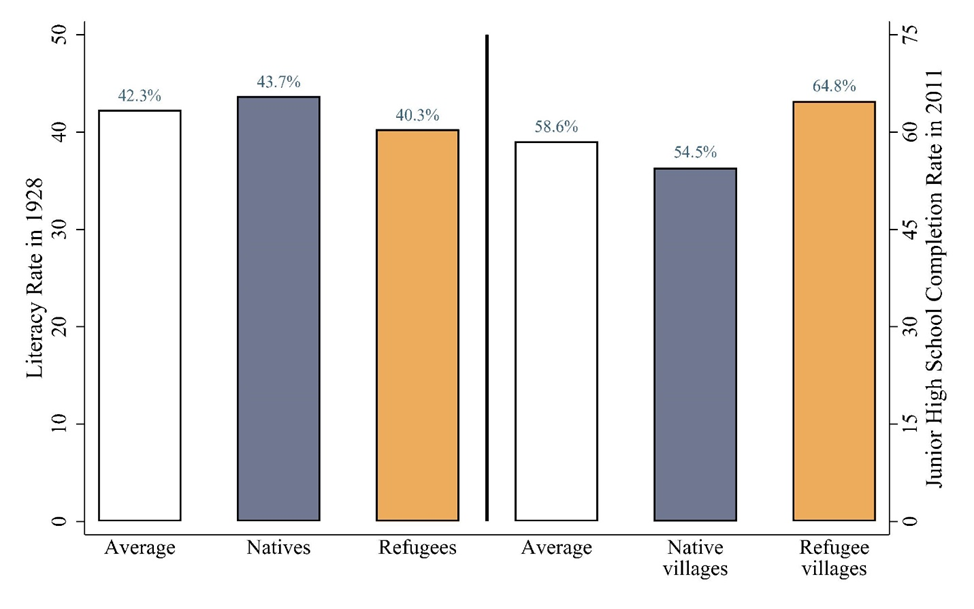

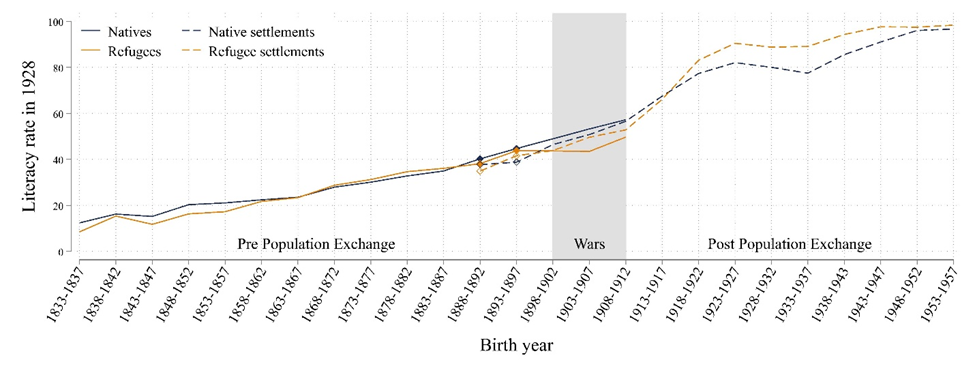

Our work examines the uprootedness hypothesis in the Greek context, utilising census data spanning over a century. We compare educational outcomes across predominantly refugee settlements (where the share of refugees in 1928 exceeded 80% or other high cut-offs) and autochthonous rural communities before and after the 1923 Greco-Turkish Forced Population Exchange. Figure 3, which zooms in on Macedonia and West Thrace, where 80% of rural refugees settled, shows that literacy rates and primary school completion rates were lower among refugees and predominantly refugee settlements compared to native ones. In the countryside, Native and refugee literacy was 43.7% and 40.3%, respectively; while the share of the population with completed primary schooling was 12.1% and 16% in predominantly refugee settlements and autochthonous communities, respectively (Panels (a)-(b)). Additionally, using data dating back to the mid-19th century, we document similar trends in literacy among the autochthonous population (living mainly in Greece at the time) and refugees (living primarily in the Ottoman Empire) (Figure 4). However, after their forced relocation and settlement in Greece, refugees caught up and eventually surpassed the natives. In the 2011 General Population Census, former refugee communities had a 10-percentage-point edge in junior high school completion over autochthonous rural settlements (64.8% and 54.5%, respectively).

Figure 3: Literacy in 1928 and junior high school completion in Northern Greece

Figure 4: Literacy across rural refugees and natives by birth cohort in Northern Greece

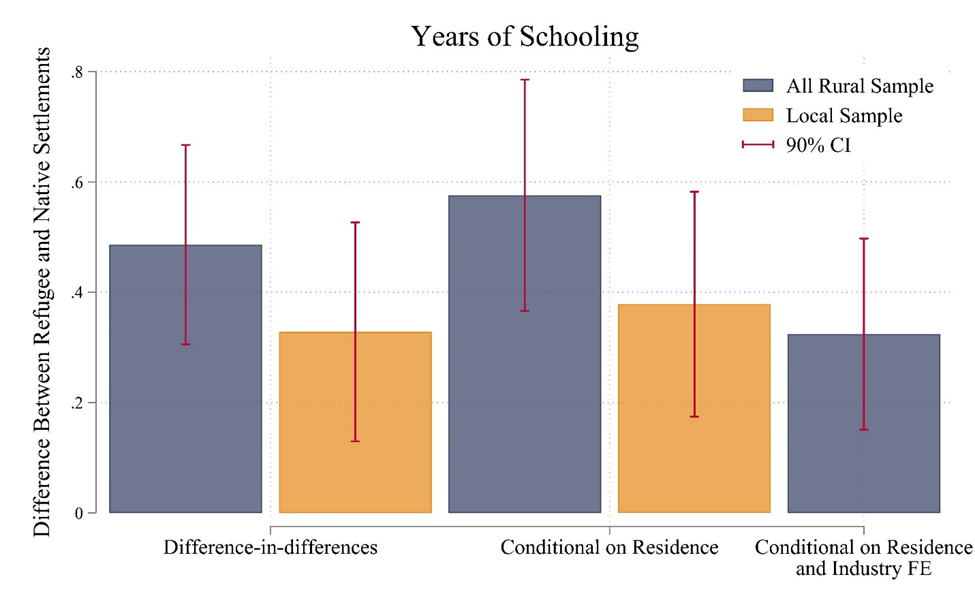

Our econometric specifications (Figure 5) delve into these before-and-after statistics, accounting for the general rise in education, unobservable settlement features that may have shaped the initial location and human capital investments, and individual characteristics. The refugee-native human capital gap, present when comparing Greeks from the same province (admin-4 unit) and settlements no more than 25 (or even 10) kilometres apart (so-called Local Sample), is approximately half to three-fourths of a schooling year, a non-negligible effect given an average of about eight years. The refugee-native schooling gap in education is present and similar among internal migrants (who moved from their birthplace, typically in Greece’s big cities) and non-migrants (who reside at their birthplace). In addition, refugees' higher education, for both men and women, applies when comparing Greeks working in the same sector, suggesting that refugees’ switch to human capital stems from a deeper valuation.

Figure 5: Econometric estimates of refugee-native gap in schooling year

The impact of uprootedness on refugee propensity for skill transferability

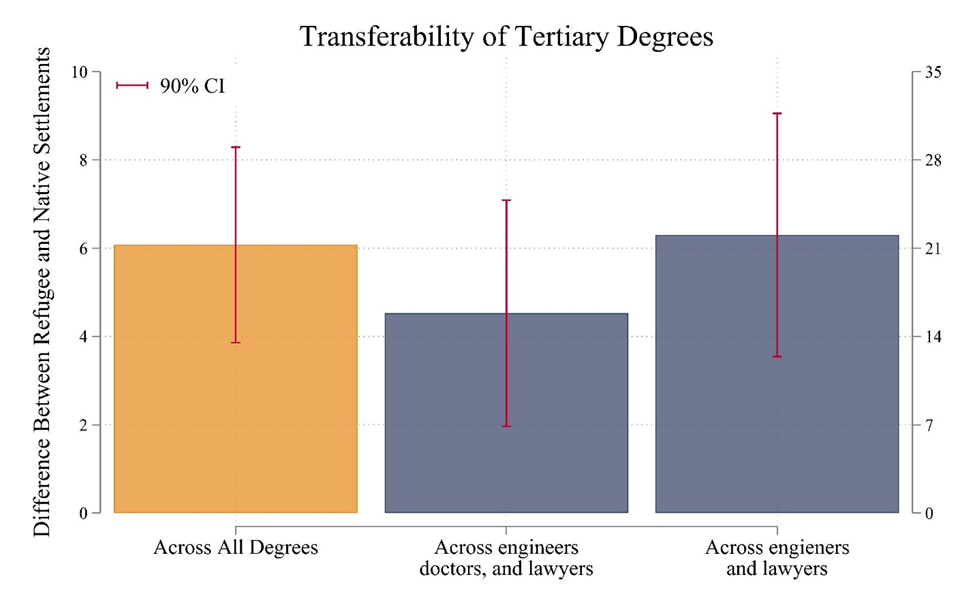

A key aspect of the uprootedness hypothesis pertains to the portability of human capital. Using detailed information on university/college degrees from the 2011 population census, we explore the portability aspect among Greeks with tertiary education. Using ChatGPT-4, we first classify 266 fields of study as relatively more or less portable. Examples of degrees with transferable skills include law, medicine, engineering, and accounting. Examples of degrees with limited transferability include those from military and police academies, theology, and teaching. Then, we examine the role of refugee ancestry in the likelihood of obtaining a degree with transferable skills among Greeks with tertiary education.

Our analysis, summarised in Figure 6 (left bars) suggests that college graduates from refugee settlements have a 6.1 percentage points (pps) higher likelihood of pursuing a tertiary degree with transferable skills than college-educated Greeks from (proximate) native settlements in the same province, with similar observable characteristics living in the same municipality in 2011 (which can either be their birth one or a another one typically in big cities). The magnitude is not small, as about two-thirds of Greeks from non-refugee rural settlements complete a degree with portable skills. We repeat the analysis focusing only on law, medicine, and engineering graduates, the most selected college-educated Greeks. Third- and fourth-generation refugees have a significantly higher propensity, ranging from 8.5 pps to 16 pps, to study medicine and engineering, as opposed to law, which, due to the legal system’s idiosyncrasies and tight regulations, is not easily transferable across borders (Ayal and Chiswick 1983, Brenner and Kiefer 1981). This finding supports the old notion of uprootedness, which suggests that forced relocation can have lasting impacts by altering the value placed on transferable human capital investments (Stigler and Becker 1977, Kessel 1958).

Figure 6: Displacement and college skill portability across rural native and refugee birth settlements

Further evidence on refugee career trajectories

Lastly, we exploit the rich variation in refugees’ displacement trajectories (some of which were more violent and abrupt than others), the heterogeneity of their linguistic and occupational background (with some origin communities specialising on herding, others in agriculture, and others in commerce), and settlements in the Greek countryside to shed light on additional mechanisms. Overall, refugees' educational gains are widespread, affecting those settling in new or existing (former Muslim) villages, those from more rural or urban areas, and regions with varying farming potential. Refugees from Cappadocia who did not speak Greek experienced smaller educational gains, illustrating that linguistic barriers can impede the integration of refugees and migrants even when they share religion and cultural heritage with the host population.

The displacement-education nexus is slightly more substantial in settlements with more diversity among refugees, suggesting some benefits from mixing. Refugees in more densely populated, industrial, and service-oriented provinces in Greece, where demand for educated workers was higher, tended to do even better. However, regardless of where they lived or their background, refugee descendants consistently chose university degrees with transferable skills, even in places that were not in demand.

Policy lessons and implications: Refugees and long-term growth

So, where do these results leave us? When the refugees first arrived in Greece, most destitute, ill, and exhausted, few in the international community would have expected them to catalyse the country’s reconstruction and overtake the native population in terms of education. We hope that the conceptual appeal of the uprootedness hypothesis and other works on displacement (mainly Becker et al. 2020) yielding similar results allow for some cautious generalisation. However, hope is conditional.

A hundred years ago, the League of Nations played an instrumental role in this process by setting up the RSC, whose multifaceted financial support and technical assistance was chief. International assistance was first-order, with the Bank of England providing bridge finance and assisting the RSC to raise much-needed funds. Philanthropic aid was also instrumental; the Near East Relief Fund, the very first large-scale humanitarian fund (and a predecessor to USAID), would support refugees in the initial months and subsequently with housing (Morgenthau 1929, Simpson 1929). The Greek state gave refugees full citizenship rights upon arrival, while many foreign countries opened their doors via the Nansen passport given to refugees. Despite considerable discrimination in the initial years, the Greek government made a good faith effort to integrate refugees.

As the Eastern Mediterranean and the Near and Middle East experience large refugee outflows, our study highlights a historical lesson: forcibly displaced people, driven by their eagerness to learn and invest in education, can become powerful engines of growth. However, realising this potential depends on providing them with a fair chance.

References

Ayal, E B and B Chiswick (1983), “The economics of the diaspora, revisited”, Economic Development and Cultural Change, 31: 861–875.

Bauer, T K, S Braun, and M Kvasnicka (2013), “The economic integration of forced migrants: Evidence for post-war Germany”, Economic Journal, 123(571): 998–1024.

Becker, S O and A Ferrara (2019), “Consequences of forced migration: A survey of recent findings”, Labour Economics, 59: 1–16.

Becker, S O, I Grosfeld, P Grosjean, N Voigtländer, and E Zhuravskaya (2020), “Forced migration and human capital: Evidence from post-WWII population transfers”, American Economic Review, 110(5): 1430–1463.

Botticini, M and Z Eckstein (2012), "The Chosen Few: How Education Shaped Jewish History", Princeton University Press.

Brenner, R and N M Kiefer (1981), “The economics of the diaspora: Discrimination and occupational structure”, Economic Development and Cultural Change, 29: 517–534.

Ciccone, A and J Nimczik (2023), “The long-run effects of immigration: Evidence across a barrier to refugee settlement”, University of Mannheim Working Paper.

Kessel, R A (1958), “Price discrimination in medicine”, Journal of Law and Economics, 1: 20–53.

Michalopoulos, S, E Murard, E Papaioannou, and S O Sakalli (2025), “Uprootedness, human capital, and skill transferability”, NBER Working Paper 33586; EPR Discussion Paper 20072.

Murard, E (2023), “Long-term effects of the 1923 mass refugee inflow on social cohesion in Greece”, World Development, 170: 106311.

Morgenthau, H S (1929), "I Was Sent to Athens", Doubleday, Doran, and Co.

Peters, M (2022), “Market size and spatial growth – Evidence from Germany’s post-war population expulsions”, Econometrica, 90(5): 2357–2396.

Sarvimäki, M, R Uusitalo, and M Jäntti (2022), “Habit formation and the misallocation of labor: Evidence from forced migrations”, Journal of the European Economic Association, 20(6): 2497–2539.

Simpson, J H (1929), “The work of the Greek Refugee Settlement Commission”, Journal of the Royal Institute of International Affairs, 8(6): 583–604.

Stigler, G J and G S Becker (1977), “De gustibus non est disputandum”, American Economic Review, 67: 76–90.