As the global refugee crisis escalates, there is a growing need for evidence on refugee housing policy. Evidence from Jordan suggests that housing subsidies for Syrian refugees had limited benefits for refugee well-being while worsening social cohesion.

Editor’s note: Read more about Refugees and Forcibly Displaced Populations in our VoxDevLit.

As forced displacement continues to escalate, reaching a total of 120 million individuals in May of 2024 (UNHCR 2024), there is an urgent need for evidence to guide refugee-hosting policy decisions. Roughly half of refugees globally live outside of camps, yet there remains limited evidence on how best to improve housing stability outside of camp settings (Kumar 2021, Agness 2023).

Refugees’ economic and social vulnerability suggests that they may require initial targeted support to find a stable place to stay outside of camps. In fact, housing and neighbourhood programmes in non-humanitarian settings, such as housing vouchers, public housing construction, and transfer of home titles have shown transformative effects for vulnerable communities (Chetty et al. 2016, Kling et al. 2007, Kumar 2021, Ludwig et al. 2013). Yet, offering targeted housing support to refugees—despite its huge potential to improve refugee’s welfare—may create tensions in local communities when hosts are excluded from these programmes. For example, large refugee inflows may increase housing prices (Rozo and Sviastchi 2021), and other vulnerable populations may view refugee-exclusive assistance as unfair.

We experimentally examine the trade-off between the well-being effects of a refugee housing programme and the social tensions it may induce from local communities who are also vulnerable but ineligible due to their non-refugee status. This trade-off is of particular concern for refugee assistance: most refugees rely on humanitarian or government aid to meet many of their basic needs, but are also at risk of experiencing social exclusion or even xenophobia from hosting country citizens. This tension could reduce public support for assistance programmes and may set recipients back by eroding important social relationships.

Our study takes place in the context of an urban shelter programme that provided housing subsidies to Syrian refugees in Jordan, which hosted over 650,000 registered Syrian refugees during the study period—representing 5.5% of the 11.3 million population.

The origins of a housing subsidy programme for refugees

The Urban Shelter Program was implemented by a large non-profit organisation that supports refugees in Jordan. The programme was designed to address the high levels of housing insecurity and rental debt faced by refugees in these communities, consisting of a signed contract between the non-profit organisation and a local landlord that was already hosting a refugee. In exchange for continuing to provide housing to the refugee household, the landlord received a payment equivalent to the rent price of their property for 9 to 18 months depending on the contract negotiation. The landlord also received additional financial funds for housing upgrades, such as mould removal, securing windows and front doors, installing doors in bathrooms, or covering bare floors in the refugee’s current residence. The average value of the contract was US$2,200.

Designing a housing subsidy programme for refugees

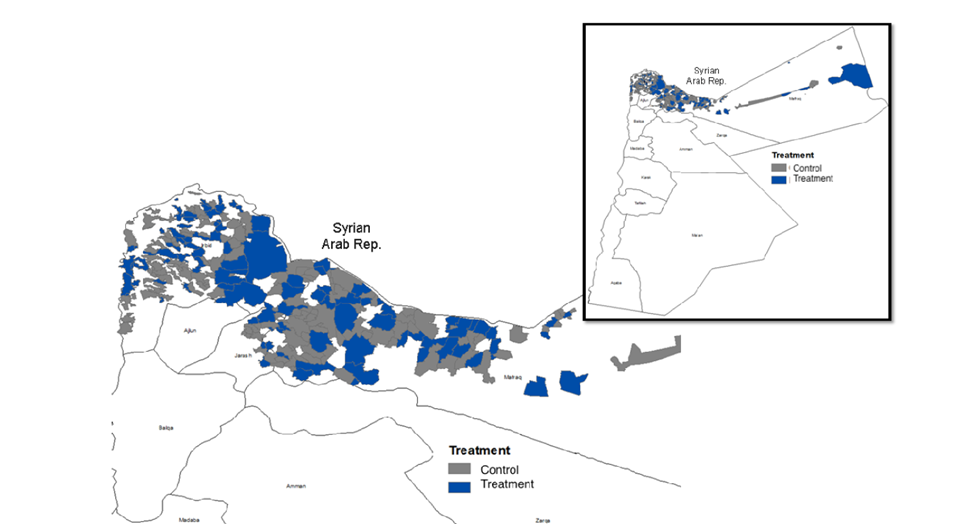

The programme was randomised at the geographic location in 158 localities in the governorates of Mafraq and Irbid (Figure 1). Conditional on eligibility, everyone who applied in the treatment group localities was offered the programme. Only individuals whose baseline vulnerability measured fell within the middle 80% were eligible for randomisation. The remaining 20% were excluded from the study, with the 10% most vulnerable always receiving assistance, and the 10% least vulnerable deemed ineligible for participation. In total, 2,200 individuals participated in our research.

Figure 1. Randomisation at the locality level in Mafraq and Irbid

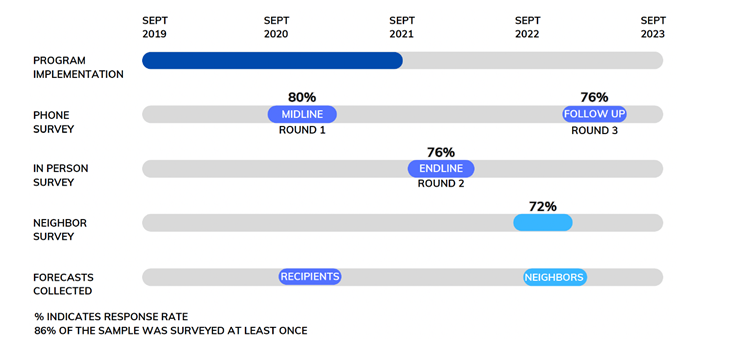

We collected four rounds of field surveys to evaluate the effects of the programme on refugees’ well-being (midline, endline, and follow-up) and Jordanian neighbours’ perceptions and attitudes toward refugees (in 2022). We also collected two rounds of forecasts from research and humanitarian implementation experts on the potential effects of the programme. Neighbours were selected in adjacent or close dwellings to the refugee households that participated in the study one year after the implementation ended. 86% of the total sample of refugees was surveyed at least once (Figure 2).

Figure 2. RCT, data collection, and forecasts timeline

Our research was successful at achieving balance on observable covariates between the treatment and the control groups. However, take-up for the programme was relatively low and close to 33%. Some housing structures did not meet the programme requirements by, for example, being too developed to need additional investments or too precarious to be liveable, which contributed to the low take-up rate. There was also anecdotal reserve from landlords to sign a contract with the NGO, indicating they may have favoured their existing informal arrangements.

We preregistered the experiment and pre-specified primary and secondary outcomes of analysis to ensure transparency. Our main refugee primary outcomes included housing quality, housing expenditures, total consumption, adult depression, and child socio-emotional well-being. Our primary pre-specified Jordanian neighbour outcomes included policy preferences, economic attitudes, social attitudes, and altruism toward Syrians in the form of an incentivised dictator game.

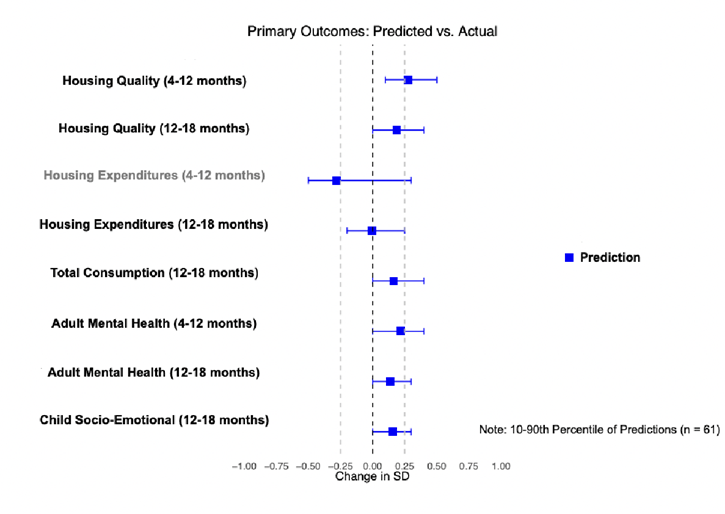

Experts predicted positive impacts on refugee well-being

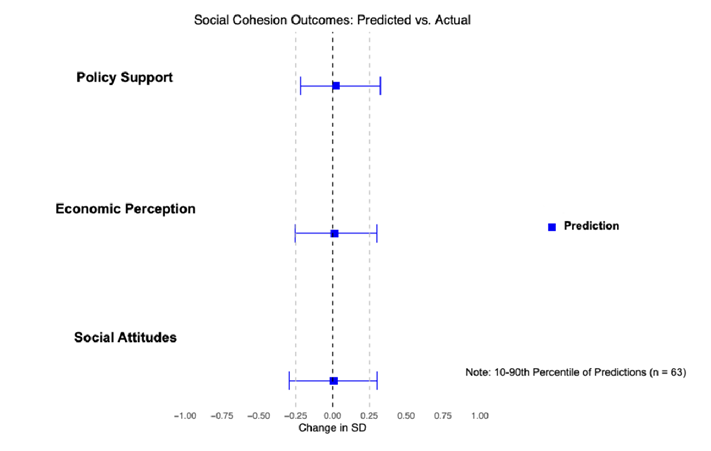

We collected forecasts on the impacts of the programme on our primary outcomes from approximately 60 policy and academic researchers. Our results suggest that implementers and researchers expected moderate positive impacts of the programme on refugee well-being (Panel A, Figure 3) and negligible effects on neighbours’ social and policy attitudes toward refugees (Panel B, Figure 3).

Figure 3. Experts’ predicted results of the intervention

Panel A. Refugee well-being

Panel B. Neighbour’s social cohesion outcomes

The housing subsidy programmes had limited positive effects on refugees

One of our main empirical findings is that we detect no significant positive impacts of the housing assistance programme for refugees on the pre-specified primary outcomes, except for housing expenditures where there is an expected decrease in spending. Another unexpected outcome is that the socio-emotional well-being of children in treated households decreases substantially, by 0.34 standard deviations on average (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Pooled treatment effects across rounds

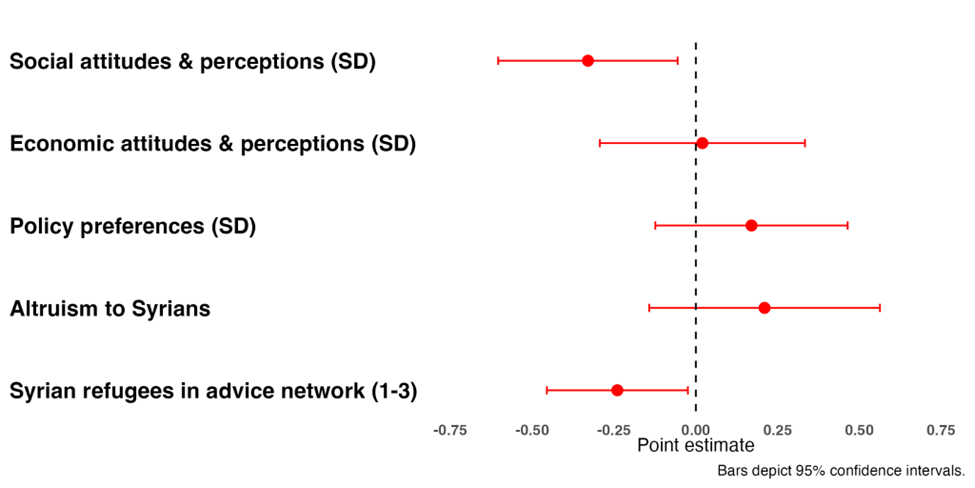

Our second main finding is that the refugee-targeted housing subsidy programme led to a meaningful and statistically significant deterioration in community perceptions towards Syrian refugees among the Jordanian neighbours in treatment households. We estimate a 0.33 standard deviation unit decrease in an index of their social attitudes and perceptions of refugees. Our analysis also shows that neighbours become better informed about how much assistance Syrian refugees receive.

There is no impact on neighbours’ own economic outcomes. We speculate that the substantial transfers received by treated refugee households were observed by Jordanian neighbours and led to tensions in some cases, perhaps since neighbours also live in the same relatively poor neighbourhoods as the refugees and are typically not well-off themselves. The visibility of assistance in this case–including construction activity in the treated housing units–may have raised the salience of the intervention relative to some other forms of aid (i.e. mobile money transfers or health care subsidies) that are easier to keep private (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Impacts of the programme on neighbour’s attitudes toward refugees

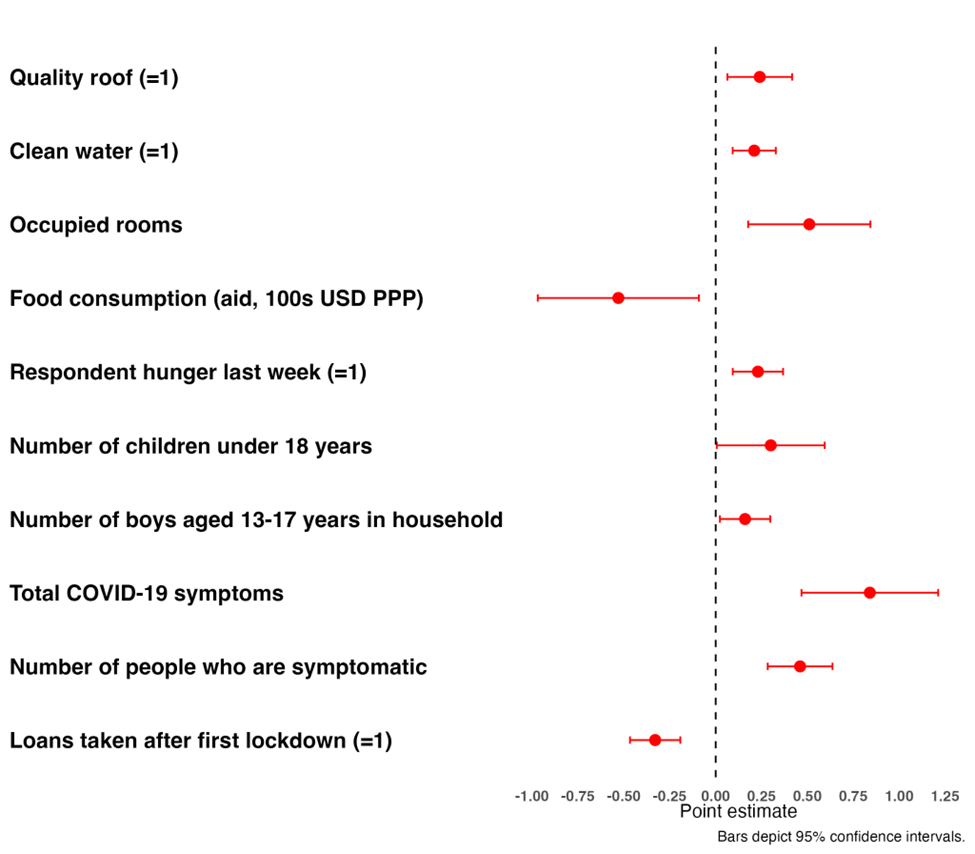

Disaggregating the data by survey round assists in understanding the predominantly null impacts on consumption and adult well-being. In the short run (while the programme was ongoing), treated households experienced meaningful gains in housing quality and financial stability: they reported increased access to clean water and less reliance on loans. These findings indicate that programme investments were able to achieve some of their immediate goals, especially in terms of improving the housing quality experienced by recipients and preventing them from accumulating more debt (much of which is rental related debt in this population).

However, both food security and self-reported health worsened: household hunger increased for several measures and more household members exhibited COVID-19 symptoms. We find several pieces of evidence that these negative effects result from the unanticipated redistribution of aid. We document a meaningful and statistically significant reduction in food aid that treatment households report receiving, roughly equivalent to 10% of monthly pre-pandemic income. There is also suggestive evidence that treated households received an inflow of additional household members (especially adolescents males), further diluting programme benefits in per capita terms (Figure 6).

Data from the second round of surveys (collected shortly after assistance had ended) indicates that treated households continued to report reduced housing expenditures as well as increased savings, but, at the same time, reported a significant decrease in subjective well-being.

In the final survey round, one to two years after assistance had ended, the only significant treatment effect that survives a multiple testing adjustment is the substantial decrease in child socio-emotional well-being. The evolution of the effects of the refugee housing assistance programme over time suggest a possible link between the negative impacts on child well-being and neighbour attitudes. While all other treatment effects on refugee households dissipate by the final round of surveying (conducted more than a year after assistance had ended), the negative impacts on child outcomes persist, and the negative impacts on neighbours’ perceptions towards refugees are collected at a similar time point (about a year after programme implementation had ended). For example, two components of the neighbour social attitudes index that are statistically significant capture whether the children in Jordanian households have Syrian refugee friends, and whether adult Jordanian neighbours have close Syrian friends. Taken together, the timing of child effects and the data from neighbours offer suggestive evidence that the deterioration in child well-being may be driven by worse social relations with the treated refugee households’ Jordanian neighbours.

Figure 6. Selected Midline Impacts

Policy implications for housing subsidy programmes for refugees

Our findings indicate that the housing assistance programme offered limited short-run economic improvements that dissipated following the programme, while negative psychological and social cohesion effects proved more lasting. The negative response from neighbours parallels existing research on targeted transfers, which has documented negative psychological impacts on nearby non-recipients of cash transfers in some cases, although the evidence is notably mixed (Haushofer and Shapiro 2016, Haushofer et al. 2015, Baird et al. 2013, Egger et al. 2022). Unlike the above studies, this paper finds that tensions among non-recipients persist more than a year after the transfer implementation period, and that these negative effects may even undermine the well-being of programme recipients and their children via reduced social ties between Jordanians and refugees, highlighting the fragility of social cohesion between refugees and host country citizens (Zhou 2019).

If programmes like this are in fact not improving refugees’ lives, an urgent question revolves around the feasibility of other policy approaches. A growing body of research demonstrates that direct cash transfer programmes yield meaningful improvements for households, at least while assistance is ongoing (Hidrobo et al. 2014, Özler et al. 2021, Quattrochi et al. 2022, Moussa et al. 2022, Aygün et al. 2024, Haushofer and Shapiro 2016), and cash is one immediate alternative that would likely be less observable to non-recipients. In line with this, and echoing the largely null 6 evaluation results, a large majority (70%) of refugee respondents stated in the endline survey that they would have preferred cash assistance of equivalent value to the rental subsidy. At the same time, such cash assistance may not do much to improve the structural impediments to economic and social integration facing refugees in most settings.

References

Agness, D (2023), “Housing and human capital: Condominiums in Ethiopia,” 3ie Registry.

Aygün, A H, M G Kırdar, M Koyuncu, and Q Stoeffler (2024), “Keeping refugee children in school and out of work: Evidence from the world’s largest humanitarian cash transfer program,” Journal of Development Economics, 168: 103266.

Baird, S, J De Hoop, and B Özler (2013), “Income shocks and adolescent mental health,” Journal of Human Resources, 48(2): 370–403.

Chetty, R, N Hendren, and L F Katz (2016), “The effects of exposure to better neighbourhoods on children: New evidence from the Moving to Opportunity experiment,” American Economic Review, 106(4): 855–902.

Egger, D, J Haushofer, E Miguel, P Niehaus, and M Walker (2022), “General equilibrium effects of cash transfers: Experimental evidence from Kenya,” Econometrica, 90(6): 2603–2643.

Haushofer, J, J Reisinger, and J Shapiro (2015), “Your gain is my pain: Negative psychological externalities of cash transfers,” Unpublished manuscript.

Haushofer, J, and J Shapiro (2016), “The short-term impact of unconditional cash transfers to the poor: Experimental evidence from Kenya,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(4): 1973–2042.

Haushofer, J, and J Shapiro (2018), “The long-term impact of unconditional cash transfers: Experimental evidence from Kenya,” Unpublished manuscript.

Hidrobo, M, J Hoddinott, A Peterman, A Margolies, and V Moreira (2014), “Cash, food, or vouchers? Evidence from a randomized experiment in northern Ecuador,” Journal of Development Economics, 107: 144–156.

Kling, J R, J B Liebman, and L F Katz (2007), “Experimental analysis of neighborhood effects,” Econometrica, 75(1): 83–119.

Kumar, T (2021), “Home-price subsidies increase local-level political participation in urban India,” Journal of Politics Forthcoming.

Ludwig, J, G J Duncan, L A Gennetian, L F Katz, R C Kessler, J R Kling, and L Sanbonmatsu (2013), “Long-term neighborhood effects on low-income families: Evidence from Moving to Opportunity,” American Economic Review, 103(3): 226–231.

Moussa, W, N Salti, A Irani, R Al Mokdad, Z Jamaluddine, J Chaaban, and H Ghattas (2022), “The impact of cash transfers on Syrian refugee children in Lebanon,” World Development, 150: 105711.

Özler, B, Ç Çelik, S Cunningham, P F Cuevas, and L Parisotto (2021), “Children on the move: Progressive redistribution of humanitarian cash transfers among refugees,” Journal of Development Economics, 153: 102733.

Quattrochi, J, G Bisimwa, P Van Der Windt, and M Voors (2022), “Cash-like vouchers improve psychological well-being of vulnerable and displaced persons fleeing armed conflict,” PNAS Nexus, 1(3): pgac101.

Rozo, S V, A Quintana, and M J Urbina (2023), “The electoral consequences of easing the integration of forced migrants,” Unpublished manuscript.

UNHCR (2024), "Refugee statistics."

Zhou, Y Y (2019), “How refugee resentment shapes national identity and citizen participation in Africa,” Unpublished manuscript.