Tax amnesties are a popular tool used by governments to encourage individuals and firms to partially fulfil their outstanding tax obligations, yet little is known about their effectiveness. Evidence from the Dominican Republic shows how partial forgiveness policies, when combined with strong deterrence messages and strict enforcement signalling state capacity, can increase short-run revenue while having little impact on long-term tax revenue.

Editor’s note: For a broader synthesis of themes covered in this article, check out our VoxDevLit on Taxation.

Governments around the globe use partial debt forgiveness policies—known as tax amnesties—to collect short-run revenue while allowing debtors to make amends for past misdeeds. Policymakers and researchers, however, have expressed concern over such amnesties backfiring (Malik and Schwab 1991). Critics argue that few debtors may take up the amnesty, limiting the short-run gain. Taxpayers may also view this as a signal of low state enforcement capacity, lowering their perceived cost of retaining known or hidden debt, and opt not to repay. Amnesties could additionally worsen long-run tax collection if taxpayers' worsened perceptions of state capacity lead to future tax evasion, particularly among non-debtors (Leonard and Zeckhauser 1987). These issues of tax collection are especially important in low and middle-income countries with weak enforcement (Waseem et al. 2016).

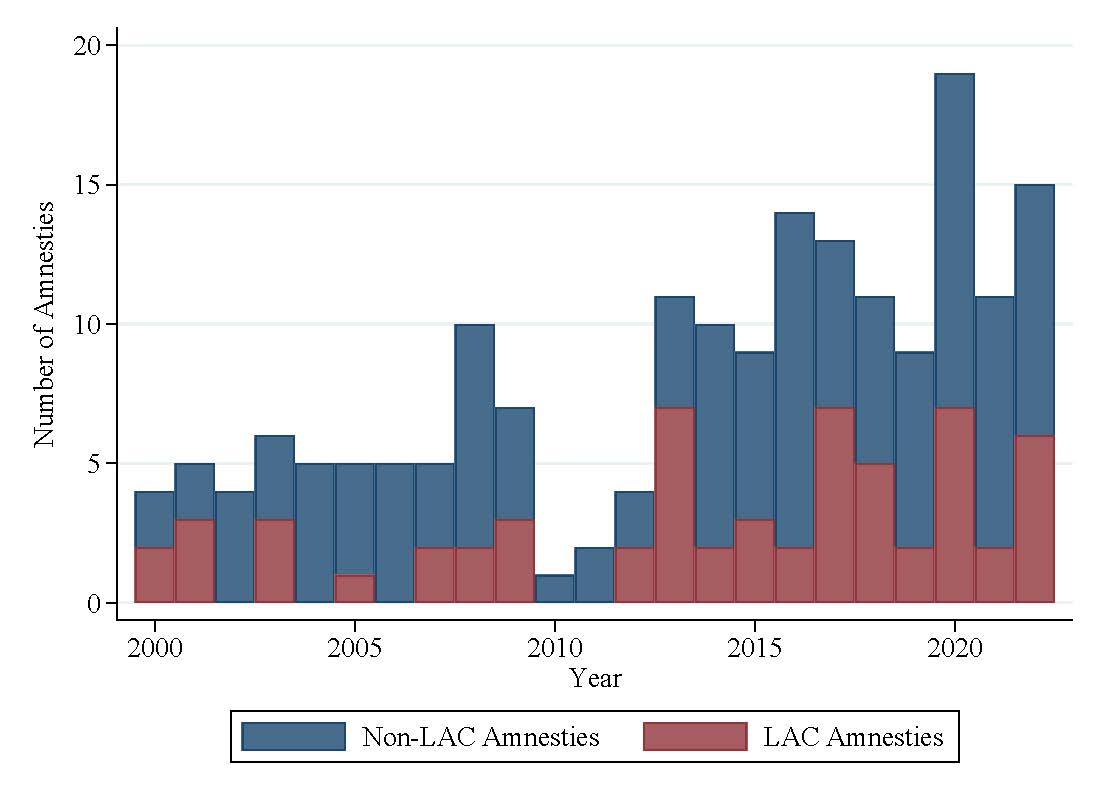

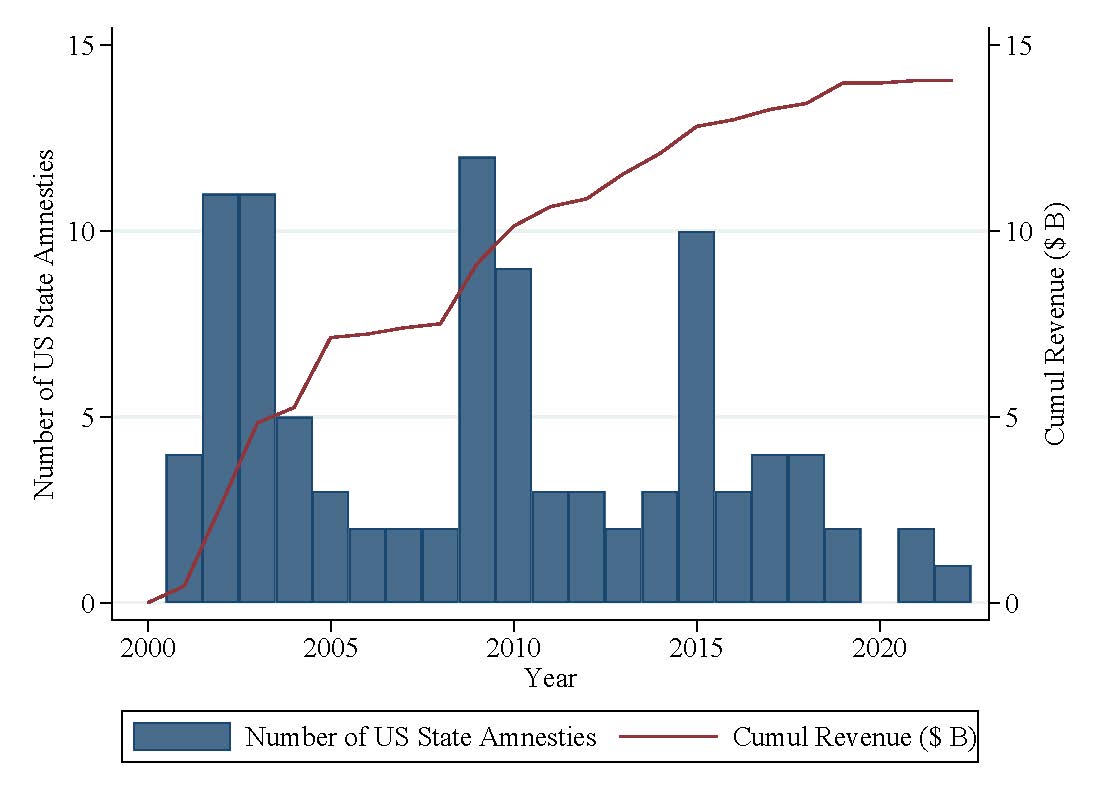

Despite these concerns, tax amnesties are common. Since 2000, 184 national amnesties have been introduced across 84 countries, and many more have been enacted at the subnational level. These policies have become increasingly common since the COVID-19 pandemic when governments faced a large, unexpected sudden need for additional revenue. Though tax amnesties offer one potential means of raising revenue during times of hardship, alongside other fiscal policies (Hoang et al. 2020, Löyttyniemi 2020), there is little causal empirical evidence on their costs and benefits.

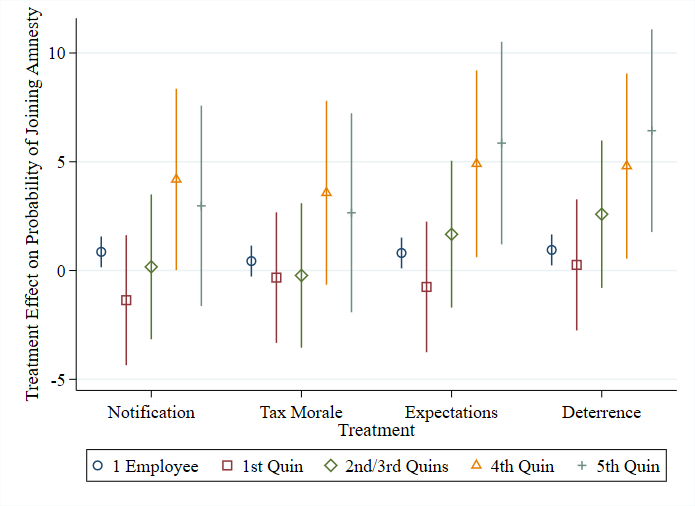

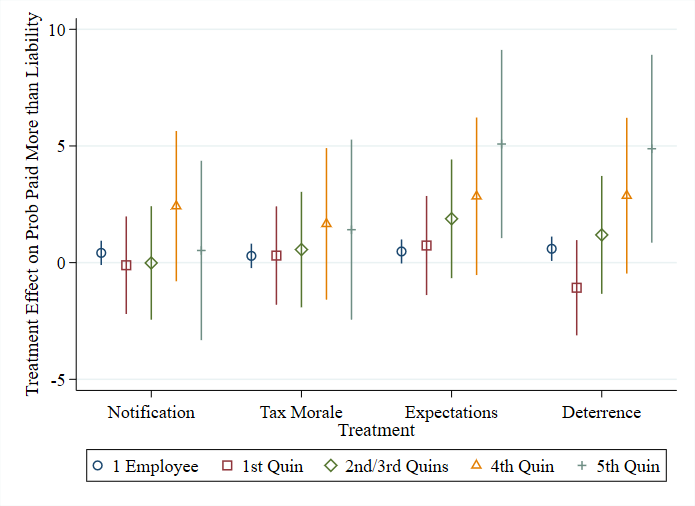

Figure 1: Treatment effects on joining amnesty to resolve known and hidden debts

(a) International amnesties (b) US amnesties

In recent work (Gil et al. 2024), we partnered with the Dominican Republic Tax Authorities (IRSDR) to better understand and measure the short- and long-run benefits and costs of implementing an amnesty. We conducted a field experiment with a pool of 125,452 tax debtors— both firms and individuals—who collectively owed USD 5.2 billion (5.5% of GDP) in back taxes. As part of the experiment, different tax debtors receive different information directly from the IRSDR about the amnesty, as well as the benefits of joining and costs of not joining. In doing so, this work sheds light on how governments can most effectively implement tax amnesties.

When are tax amnesties effective?

Given the concerns about the potential short- and long-run effectiveness of tax amnesties, we designed a natural field experiment to test when tax amnesties work. We allocated different tax debtors into five groups who each received different information from the IRSDR. We then compared how receiving a letter and the specific content of the letters affected whether they chose to join the amnesty, how much they paid in both known and hidden debt when joining, and how much they paid in income taxes after the amnesty ended.

About one-fifth of the debtors received no direct contact from the IRSDR about the amnesty programme as part of the experiment. These firms and individuals made up our control group. We compared their behaviour to similar tax debtors who received specific information about the amnesty in order to measure when an amnesty is effective, and for whom. The remaining tax debtors received a notification with details about the benefits of joining the tax amnesty, along with instructions on how to join—one-fifth received only this notification. Another fifth received the notification along with an appeal to the need for government funding during the pandemic to emphasise tax morale (Luttmer and Singhal 2014, Jensen and Besley 2015). The next fifth received the notification and an expectations message where debtors were additionally told that this was their last chance to receive partial forgiveness for repaying. This message sought to increase the perceived cost of holding onto both known and hidden debt in the future. The final fifth received the notification plus a deterrence warning that failure to pay tax debt is punishable by fines and even imprisonment.

Each of our conditions highlighted a different feature of amnesty design and incentives. Based on our experiment, we then compared the behaviour of tax debtors in the control group to each treatment group in order to understand which features have the largest effect on short- and long-run revenue. Beyond the design of incentives for an effective amnesty programme, governments must also ensure that tax debtors understand the benefits of joining (Castro and Scartascini 2019).

How can governments optimise tax amnesty programmes?

A key concern for governments considering tax amnesties is the possibility that tax debtors will not participate. In which case, the government will receive little additional revenue, while signalling to tax debtors that enforcement is low. During the 2020 amnesty in the Dominican Republic, only 18.2% of taxpayers in our control group, who were not directly contacted about the amnesty, chose to resolve known debts, paying only 8.6% more into the amnesty than their known liability—our measure of a taxpayer's decision to resolve their hidden debts and past evasion. Importantly, larger firms (in terms of number of employees) are more likely to join and resolve both known and hidden debt.

All messages increased amnesty take-up among debtors by 3.5-8%, compared to tax debtors in the control group that did not receive a notification from the IRSDR. While all types of notifications increase take-up, only the deterrence message increased the total amount tax debtors paid into the amnesty, as well as what they paid in hidden debt previously unknown to the IRSDR. This behavioural change is largely driven by firms, and only the deterrence message induced individuals to join with a meaningful increase in the amount those individuals pay into the amnesty.

Beyond the average effects of the amnesty, we restricted the analysis to firms and studied how the messages affected their behaviour based on their number of employees. Measuring the effect on large firms is important for policy as they account for the majority of revenue: the largest 1% of firms remit over 60% of the tax revenue from the corporate income tax in the Dominican Republic and owe 87% of all known debt in our data.

We find that the deterrence and expectations about future amnesty messages increase the likelihood that the largest firms resolve both known and previously hidden debt. Figure 2 shows the percentage point difference in the likelihood of resolving known debt (Panel a) and hidden debt (Panel b), compared to control group debtors with a similar number of employees. Our estimates suggest that, for the fifth quintile firms, the deterrence message increases the participation rate in the amnesty programme from 44.7% to over 50%. This message has a considerable effect on fourth quintile firms as well: a 5-percentage point increase from the control mean of 35.3%. The expectations treatment has similarly large effect sizes on both groups of around 5 percentage points. Both of these messages may signal credibility of tax enforcement and the costs of evasion. Although it may be politically infeasible in many countries to implement very large penalties for evasion, our results suggest that changing the frequency of amnesty programmes can be nearly as effective at reducing evasion by the largest taxpayers.

Figure 2: Treatment effects

(a) on probability of joining amnesty (b) on probability paid more than liability

Overall, the Dominican Republic raised US$263 million from the amnesty, representing about 5% of the total known debts owed. The messages from our experiment, which aimed to increase tax debtors’ knowledge of the amnesty, tax morale, and beliefs about government future policy—as well as enforcement—induced those treated tax debtors to pay back an additional $22 million, much of which was due to deterrence messaging that are only slightly undone by reductions in subsequent tax payments. Our results suggest that amnesties can be an effective policy tool for increasing revenue when combined with strict enforcement.

Implications for tax amnesty policies

Our evidence suggests that tax amnesties can be an effective tool to raise short-run revenue from tax debtors, with minimal effects on tax revenue in the longer term. These partial forgiveness policies are especially effective when combined with strong deterrence messages and increased enforcement that signals to tax debtors, including the largest firms in the county, that the amnesty is not due to low state capacity. Where harsh punishments are infeasible, governments can instead change tax debtors’ perceptions about future forgiveness opportunities to increase take-up, which had similar effects as deterrence on the largest firms.

Finally, in addition to generating millions of dollars in tax revenue for the Dominican Republic, our findings reveal that larger taxpayers are particularly responsive to the messages—an important insight, given that they comprise a disproportionate share of total tax payments.

References

Castro, E and C Scartascini (2019), “Imperfect attention in public policy: A field experiment during a tax amnesty in Argentina”, Inter-American Development.

Gil, P, J Holz, J A List, A Simon, and A Zentner (2024), “Toward an understanding of tax amnesty take-up: Evidence from a natural field experiment”, Journal of Public Economics, 239: 105245.

Hoang, D, M Weber, and F D’Acunto (2020), “Unconventional fiscal policy to exit the COVID-19 crisis”, VoxEU.

Jensen, A, T Persson, and T Besley (2015), “Norms of tax compliance”, VoxEU.

Leonard, H B and R J Zeckhauser (1987), “Amnesty, enforcement, and tax policy”, Tax Policy and the Economy, 1: 55–85.

Luttmer, E F and M Singhal (2014), “Tax morale”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(4): 149–168.

Löyttyniemi, T (2020), “Coronataxes as a solution”, VoxEU.

Waseem, M, J Spinnewijn, A Brockmeyer, H Kleven, and M Best (2016), “Designing tax policy in high-evasion economies”, VoxEU.