Quantity and quality of infrastructure in developing countries

Information on transportation costs is sparse in developing countries, but available measures all suggest that these are very high. Road transport costs per tonne-kilometre in 2007 were 17 US cents in Central America and ranged from 4-13 US cents among countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, compared to 2 cents in the US and 4 cents in France (various sources, reported in Osborne et al. 2014). Inferring transportation costs from spatial dispersion in prices, Atkin and Donaldson (2015) estimate that trade costs increase with distance in Ethiopia and Nigeria at a rate 4-5 times higher than in the United States, and Porteous (2019) estimates that median trade costs in Africa are over five times those in other parts of the world.[1] These differential costs can arise from several sources, including low quantity and quality of physical transport infrastructure as we detail below, but also from less-studied distortions in the economy such as intermediary market power in the transportation sector.

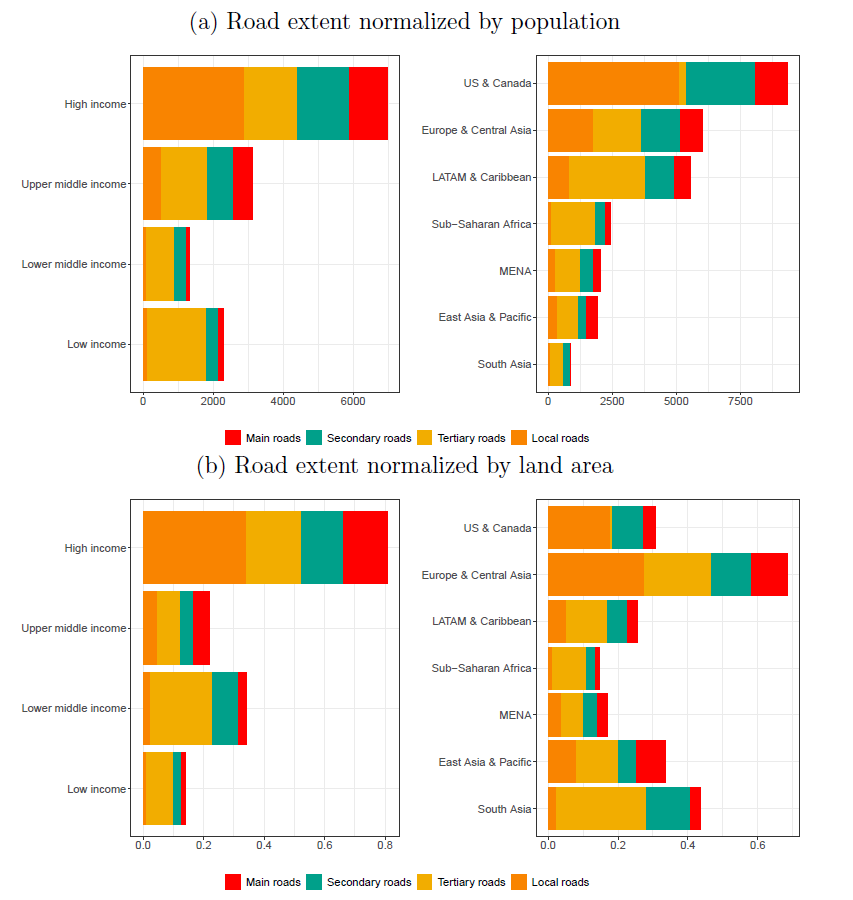

Transport infrastructure is more limited in quantity in developing countries compared with high-income countries. Figure 1 depicts total kilometres of road infrastructure by road type and income group; whether normalising the road extent by population or area, the left panel of Figure 1 shows that high-income countries on average have over twice the density of road kilometres compared to low and lower-middle-income countries. The right panels further compare the average road extents by region, highlighting the deficit faced particularly by countries on the African continent.

Figure 1: Road extent

Though less information is available about quality than quantity, what we do know suggests that transport infrastructure in developing contexts also lags behind developed countries in quality. For example, only about 13% of the road network in Brazil was paved in 2011 (Mesquita Moriera et al. 2013). Africa again faces steep challenges in infrastructure quality: Foster and Briceno-Garmendia (2010) report that the density of paved roads in Africa in 2008 was only about a quarter of that of other low-income countries. Low quality infrastructure can also impose costs due to its effects on uncertainty about travel time. For example, Iimi et al. (2019) highlight how the unreliability of rail transportation of goods in Ethiopia imposes costs on firms by forcing them to hold inventory when trains are delayed, while Datta (2012) finds that Indian firms hold smaller inventories when connected to the Golden Quadrilateral Highway system. Finally, capacity is an important dimension of quality; Coşar and Demir (2016) study road upgrades from single-lane to multi-lane expressways in Turkey, and find that shipment costs are around 70% lower on expressways compared to single-lane roads, and that trade flows respond significantly to road upgrades.

Higher transport costs in developing countries have also been shown to be attributable in part to crime and corruption. In a study on bribes along highways in Indonesia, Olken and Barron (2009) note that on average 15% of the marginal cost of a one-way trip was for illegal payments.

As for urban settings, Akbar et al. (2023b) find that poor country cities have systematically slower within-city travel speeds, and that this is mostly driven by fewer primary roads. Analogously, Akbar et al. (2023a) find that travel times in Indian cities are slow even during uncongested times, and attribute this to lower physical transport infrastructure and the geography of the city.

Placement and procurement

The literature has identified procurement and placement of infrastructure as key issues that can indirectly contribute to high transport costs in developing countries. Both procurement and placement decisions are complex processes that require strong institutions to function well. Procurement may be manipulated by government officials and firms and corruption can lead to inflated costs or low quality implementation (Chen 2023). These concerns are present in all forms of government procurement, but are especially salient in the case of construction of transportation infrastructure. In deciding where to place infrastructure, government officials may also have incentives to build roads or provide transit options that are not aligned with social welfare maximisation.

One motivation that can bias the placement of transportation infrastructure is political patronage, in which members of a shared political party or ethnic group bias the provision of services towards members of their group. Burgess et al. (2015) find striking evidence of ethnic favouritism in road development in Kenya; in non-democratic periods, districts that share the same ethnic identity as the president receive over twice as much expenditure onroads as districts with other ethnic groups. Bonfatti et al. (2022) also find evidence that road placement biasing the connection of mining areas to the coast is exacerbated during autocratic periods in West Africa during the post-colonial period, and that part of this bias is driven by ethnic favouritism. Bonilla-Mejía and Morales (2023) find evidence that road development is used as a way to influence the political positions of swing legislators in Colombia, and that road contracts under these conditions are more costly per kilometre than non-sponsored road contracts.

The large resources involved in procurement contracts and the difficulty of monitoring construction quality and maintenance costs, especially in remote areas, can also make infrastructure procurement and operation ripe for corruption and illicit activity. Procurement issues can affect many dimensions of infrastructure, including the cost of procurement, the timeliness of construction, the quality of the final product, its longevity, and the continued operation of the physical infrastructure. While difficult to measure, incidence of corruption in road procurement has been found to be high in different contexts. In cross-country analysis, measures of corruption and conflict have both been found to be strong correlates of the per-kilometre cost of infrastructure (Collier et al. 2016). In a well-known example, Olken (2007) studies village level corruption in road projects in Indonesia and notes that 27.7% of road construction costs reported to the government were never actually spent. Randomly assigning villages to either audits or an intervention designed to increase grassroots community monitoring road projects, he finds that top-down audits are successful at reducing missing costs by 8 percentage points. In India, Lehne et al. (2018) use a close election regression discontinuity design (RD) to study political patronage in road-building contracts, and find that the share of contractors whose name matches that of the winning politician increases from 4% to 7% in the term after a close election compared to the term before. Lewis-Faupel et al. (2016) find that switching to e-procurement, which reduces the scope for corruption in the procurement process, does not lead to cheaper contracts but does result in higher road quality in both India and Indonesia.

Financing

With much lower levels of government revenue in developing countries as a share of GDP, many have suggested turning to public-private partnerships (PPP) to finance transport infrastructure. While initially these arrangements were proposed as a solution to financing in low state capacity settings, time has shown that these have ultimately played a minor role in financing infrastructure to date. In addition, more research is needed to understand how PPP projects can be structured to deliver the efficiency gains they promise, since the same state capacity issues that motivate PPPs in the first place also present challenges for their implementation (Trebilcock and Rosenstock 2015). Indeed, in their review of the literature on public-private partnerships, Fabre and Straub (2023) conclude that in the case of road procurement, existing evidence suggests that PPPs are more likely to cost more and run over costs than government provision.

Another source of transit infrastructure financing that is getting increased attention is development-based and tax-based land value capture models. While understudied, there are now multiple successful examples in developing country cities using these tools to finance transit investment, operation and maintenance (Suzuki et al. 2015).

While it is clear that developing countries have less, and more costly, infrastructure, further research is also needed to inform how much investment should go to improving transportation. In the next section, we outline in broad strokes the frameworks developed by the literature on transportation infrastructure to evaluate the impacts these investments have. Before doing so, it is worth noting that a comprehensive cost-benefit analysis that can help provide policymakers better guidance regarding how much to build and the relative merits of different infrastructure types necessitates reasonable cost estimates. Unfortunately, such costing data are extremely rare and we note that this generates a gap in the analysis the literature can provide, ultimately focusing on benefits rather than more relevant benefit to cost ratios. In this sense, we highlight that more efforts such as the World Bank (2018) Road Costs Knowledge System on unit costs of road infrastructure in different locations are an extremely valuable source of information to address this gap.

References

Atkin, D and D Donaldson (2015), “Who’s Getting Globalized? The Size and Implications of Intra-national Trade Costs.” NBER Working Paper 21439.

Bonfatti, R, Y Gu and S Poelhekke (2022), “Priority Roads: the Political Economy of Africa’s Interior-to-Coast Roads.” CEPR Discussion Paper 15354.

Bonilla-Mejía, L and J Morales (2023), “Jam-Barrel Politics.” Review of Economics and Statistics, forthcoming.

Burgess, R, R Jedwab, E Miguel, A Morjaria, and G Padró i Miquel (2015), “The Value of Democracy: Evidence from Road Building in Kenya.” American Economic Review 105(6): 1817–1851.

Chen, Q (2023), “Corruption in Procurement Auctions: Evidence from Collusion between Officers and Firms.” Working Paper.

Coşar, K (2022), “Overland Transport Costs, a Review.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 10156.

Coşar, K and B Demir (2016), “Domestic Road Infrastructure and International Trade: Evidence from Turkey.” Journal of Development Economics 118: 232–244.

Collier, P, M Kirchberger, and M Söderbom (2016), “The Cost of Road Infrastructure in Low- and Middle-Income Countries.” World Bank Economic Review 30(3): 522–548.

Datta, S (2012), “The Impact of Improved Highways on Indian Firms.” Journal of Development Economics 99(1): 46–57.

Fabre, A and S Straub (2023), “The Impact of Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) in Infrastructure, Health, and Education.” Journal of Economic Literature 61(2): 655–715.

Foster, V and C Briceno-Garmendia (2010), “Africa’s Infrastructure: A Time for Transformation.” World Bank.

Iimi, A, H Adamtei, J Markland, and E Tsehaye (2019), “Port Rail Connectivity and Agricultural Production: Evidence from a Large Sample of Farmers in Ethiopia.” Journal of Applied Economics 22(1): 152–173.

Lehne, J, J Shapiro, and O Vanden Eynde (2018), “Building Connections: Political Corruption and Road Construction in India.” Journal of Development Economics 131: 62–78.

Lewis-Faupel, S, Y Neggers, B Olken, and R Pande (2016), “Can Electronic Procurement Improve Infrastructure Provision? Evidence from Public Works in India and Indonesia.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 8(3): 258–283.

Meijer, J, M J Huijbregts, K Schotten, and A Schipper (2018), “Global Patterns of Current and Future Road Infrastructure.” Environmental Research Letters 13(6): 064006.

Mesquita Moriera, M, J Blyde, C Volpe-Martincus, and D Molina (2013), Too Far to Export: Domestic Transport Costs and Regional Export Disparities in Latin America and the Caribbean. Inter-American Development Bank.

Olken, B (2007), “Monitoring Corruption: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Indonesia.” Journal of Political Economy 115(2): 200–249.

Olken, B and P Barron (2009), “The Simple Economics of Extortion: Evidence from Trucking in Aceh.” Journal of Political Economy 117(3): 417–452.

Osborne, T, M Pachón, and G Araya (2014), “What Drives the High Price of Road Freight Transport in Central America?” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 6844.

Porteous, O (2019), “High Trade Costs and Their Consequences: An Estimated Dynamic Model of African Agricultural Storage and Trade.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 11(4): 327–366.

Suzuki, H, J Murakami, Y Hong, and B Tamayose (2015), Financing Transit-Oriented Development with Land Values: Adapting Land Value Capture in Developing Countries. Urban Development Series, World Bank.

Trebilcock, M and M Rosenstock (2015), “Infrastructure Public–Private Partnerships in the Developing World: Lessons from Recent Experience.” Journal of Development Studies 51(4): 335–354.

World Bank (2018), “Road Costs Knowledge System (ROCKS) User’s Guide.” Transport and Urban Development Department.

Contact VoxDev

If you have questions, feedback, or would like more information about this article, please feel free to reach out to the VoxDev team. We’re here to help with any inquiries and to provide further insights on our research and content.